Food Traceability

Food Traceability

What Is food traceability?

Food traceability is the ability to track a given food or ingredient from its point of production (e.g. farm, abattoir, harvest at sea) through processing, manufacturing, and transportation to retail and sale to consumer.

What are the benefits of food traceability?

Food traceability is becoming a must-have in the industry to mitigate and manage risk around food safety recalls. As it becomes more widespread, industry leaders are discovering the additional benefits to traceability:

- Operational and supply chain efficiency

- Engendering consumer trust through transparency

- Reducing food loss and waste

- Market differentiation

- Enabling sustainability initiatives (such as carbon footprint or verifying legality)

- Mitigating food fraud

- Providing mechanisms to combat human rights violations

For more information, check out the FAQ and Glossary.

Toolkit Resources

The items in this toolkit have been assembled to provide you fact-based, scientific resources on this issue for your personal education and when communicating with different audiences. The American Association for the Advancement of Science offers a Communication Toolkit (that provides guidance and tips for being effective in communicating through different channels. You may want to review the AAAS toolkit as you consider using this IFT issue-specific resource in communicating about this issue with your respective networks that provides guidance and tips for being effective in communicating through different channels. You may want to review the AAAS toolkit as you consider using this IFT issue-specific resource in communicating about this issue with your respective networks.

References

Communicating to engage [Internet]. Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science. © 2018 [Accessed 2018 Feb 21].

Newsome R, Balestrini CG, Baum MD, Corby J, Fisher W, Goodburn K, Labuza TP, Prince G, Thesmar HS, Yiannas F. 2014. Applications and perceptions of date labeling of food . Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 13: 745-69.

Below are frequently asked questions related to traceability technologies to help you provide a better understanding of how these technologies can be leveraged to improve food traceability and transparency.

Why is food traceability important?

Food production is at an historical high, compounding the issues surrounding traceability. The top 20 agricultural products sold in the United States involve the production of 692 million metric tons of food (FAO 2012 ). The top 20 agricultural products globally involve the production of 6.76 billion metric tons of food (FAO 2012). This food is needed to sustain the estimated 7 billion people living today. However, it can also be a carrier for foodborne illnesses. In the United States alone, an estimated 48 million cases of foodborne illnesses occur each year and result in 3000 deaths and 128000 hospitalizations (CDC 2014a ). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) annual foodborne illness progress report, there has been no change in case rates attributed to Escherichia coliO157, Listeria, Salmonella, or Yersinia during the period of 2006 to 2008; a 75% increase in Vibrio cases and a 13% increase in Campylobacter cases (CDC 2014b ).

Education, rapid analytical testing, advancing scientific methods, advances in regulatory oversight, and Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) food safety management systems have all been vital to curbing outbreaks and reducing illness outbreaks, but foodborne illnesses till occur (as noted above). Effective and rapid traceability is a key to minimizing occurrence of foodborne illnesses. A coordinated and quickly responsive global traceability system is a crucial component of an integrated food supply chain that achieves the foodborne illness reduction goals we all desire.

Why is food traceability beneficial to implement?

Food traceability is useful for producers and manufacturers to track items for supply‐chain management purposes and for clients; and in the event of a recall, traceability is critical to protect consumer health, especially when large quantities of contaminated products are distributed across widespread markets.

Is food traceability simply meant to address food recalls?

Food traceability is about more than recalls. Being able to ascertain the origin of products and their attributes from the farm through food processing and to retail and food service and into the home is growing in importance. Increasingly, public health concerns are demanding traceability. But economic competition, which will reward those who can more effectively and reliably track and trace product back and forth through each step of the chain, will drive it.

What regulatory agencies are involved in food traceability?

Several regulatory agencies around the world are actively involved in rulemaking to improve the traceability of foods (Europa 2011; FSANZ 2011; CFIA 2012; FDA 2014; MAFF n.d.).

What is needed to enhance food traceability effectiveness?

Given the complexity of the global food system, the development of regulations and guidance to improve traceability practices across the entire food industry is a challenge. There is a need for standardized and harmonized requirements across all food sectors compared with developing specialized rules and mandates, including exceptions, for specific foods.

On the one hand, standardization would provide regulators the opportunity to resolve outbreak‐related trace‐back investigations emergency with much greater efficiency and effectiveness than possible today. On the other hand, industry stakeholders, however, need sufficient flexibility that allows them to adapt traceability requirements to specific foods and business operations. The challenge being faced today is the gap between regulatory requirements and the feasibility of industry implementation.

Several regulatory and industry initiatives have proposed frameworks for resolving this challenge. Most traceability initiatives led by the industry and industry associations for developing traceability guidance documents focus on their specific food‐product categories (Bhatt and others 2012).

How do food traceability systems function within a supply chain?

Implementing a traceability system within a supply chain requires all parties involved to link the physical flow of products with the flow of information about them. Adopting uniform industry requirements for traceability processes ensures agreement about identification of the traceable items between parties. This supports transparency and continuity of information across the supply chain.

External traceability

All traceable items must be uniquely identified, and the information be shared between all affected distribution channel participants (Natl. Fisheries Inst. 2011). The identification of products for the purpose of traceability may include assignment of a:

- Unique product identification number; and

- Batch/lot number

To maintain external traceability, traceable item identification numbers must be communicated to distribution channel participants on product labels and related paper or electronic business documents. This links the physical products with the information requirements necessary for traceability.

Internal traceability

Processes must be maintained within an organization to link identities of raw materials to those of the finished goods. When one material is combined with others, and processed, reconfigured, or repacked, the new product must have its own Unique Product Identifier. The linkage must be maintained between this new product and its original material inputs (such as batters, breading, seasonings, marinades, salt, packaging materials, and many other inputs) to maintain traceability. A label showing the Lot Number of the traceable input item should remain on the packaging until that entire traceable item is depleted. This principle applies even when the traceable item is part of a larger packaging hierarchy (such as cases, pallets, or shipment containers).

Internal and external traceability

Farm to fork traceability requires that the processes of internal and external traceability be effectively conducted. Each traceability partner should be able to identify the direct source and direct recipient of traceable items as they pertain to their process. The implication is not that every supply‐chain participant knows all the data related to traceability, but rather show proof that relevant members/partners in the supply chain have done their jobs and that information can be accessed if needed. This requires application of the one‐step‐forward–one‐step‐back principle and, further, that distribution channel participants collect, record, store, and share minimum pieces of information for traceability, as described below.

To have an effective traceability system across the supply chain:

- Any item that needs to be traced forward or backward should be identified with a globally unique identifier.

- All food chain participants should implement both internal and externally traceability practices.

- Implementation of internal traceability should ensure that the necessary linages between material inputs and finished product outputs are maintained.

Important considerations for an effective food traceability system include:

- Trading partners (farm input suppliers, farms, harvest locations or vessels, suppliers, internal transactions within a company, customers, and 3rd‐party carriers).

- Product and processing locations (any physical location such as a hatchery, cultivation site or pond, farm, vessel, dock, buying station, warehouse, packing line, storage facility, receiving dock, or a store).

- The products that a company uses or creates.

- The logistic units that a company receives or ships.

- Inbound and outbound shipments.

- Date and time metrics as appropriate.

Essential information must be collected, recorded, and shared to ensure at least one‐step‐forward−one‐step‐back traceability. This best practice is applicable to companies of any size, degree of sophistication, or location.

Identification is critical to a successful traceability program.

How do traceability programs identify products?

Usually this is accomplished by labels and any number of technologies can be employed for labeling, including simple handwritten labels and more sophisticated radio frequency identification (RFID)‐based technologies. However, barcoding remains the most common industry best practice for packaging hierarchies for shipping logistical units (such as cases, pallets, shipment containers, consumer items, and others). The barcode should at least contain the product identification number.

Businesses are encouraged to adopt electronic messaging protocols to facilitate the exchange of essential business information using unit identification as a connector between goods and information flow. Businesses are also encouraged to adopt standardized interfaces (protocols for two‐way communication) for sharing essential traceability event information within a network, thereby allowing reduction of the substantial size of data transmission along the supply chain.

To help you spread the word about traceability and traceability technologies and how they will help to improve global traceability and our global food system’s safety and accountability, IFT has assembled the following easy to share social sharable online resources.

Online Resources

- CEO: How Data Can Transform Your Traceability (no page exists)

- Implementer: Making Traceability Work for You (no page exists)

Webcasts (Free!)

- Best Practices in Food Traceability for the Processed Food Sector

- Calculating the Payback from Seafood Traceability

- Food Traceability: Important for Food Safety, Imperative for Food Defense

- Global Food Traceability Systems: Today and Near Future

- Harmonizing Food Protocols, Standards and Regulations: Chasing a Tail or Charting a Trail

- Traceability Technology and How It Improves Your Bottom Line

The items below are provided for sharing on social media about this issue. Right click on the following images to save for use on your social channels. Right click on the following images to save for use on your social channels.

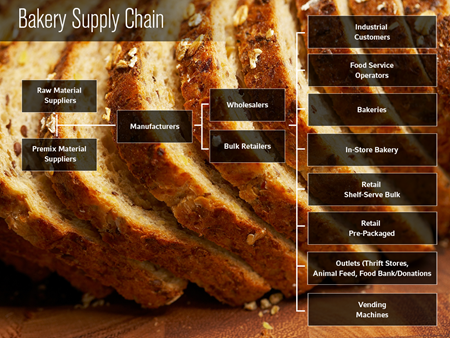

Bakery Supply Chain

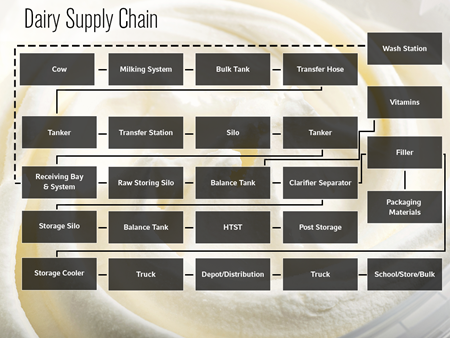

Dairy Supply Chain

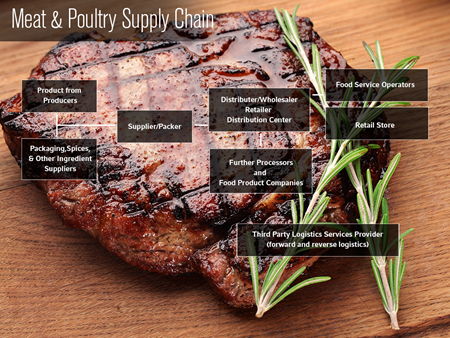

Meat & Poultry Supply Chain

Processed Food Supply Chain

Produce Supply Chain

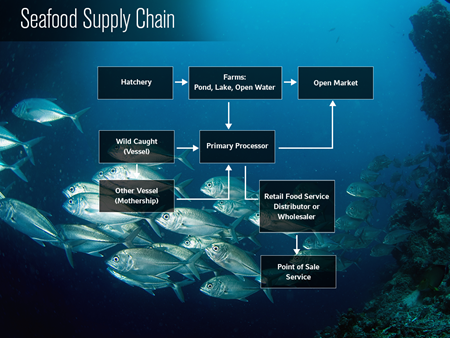

Seafood Supply Chain

In addition to shareable resources, IFT’s Global Food Traceability Center also oversees a number of pilot projects designed to test and study various product tracing practices.

- IFT: Pilot Projects for Improving Product Tracing along the Food Supply System Final Report (PDF)

- Traceability (Product Tracing) in Food Systems: An IFT Report Submitted to the FDA, Volume 1: Technical Aspects and Recommendations (PDF), 2010 (PDF)

- Traceability (Product Tracing) in Food Systems: An IFT Report Submitted to the FDA, Volume 2: Cost Considerations and Implications (PDF), 2010 (PDF)

Reports and Summaries

- Executive Summary: Project to Develop an Interoperable Seafood Traceability Technology Architecture (PDF), 2017

- Full Report: Assessing the Value and Role of Seafood Traceability from an Entire Value-Chain Perspective (PDF), 2015

GFTC conducted an extensive research and technology development project into the use and value of seafood traceability. The project team investigated the utility of traceability to reduce Hwaste, enhance consumer trust, and increase business efficiencies along the entire value chain, from catch to the consumer.

The food traceability regulations of 21 Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) countries were examined with attention to whether these regulations are comprehensive for all food commodities and processed foods.

Journal of Food Science Supplement

Presents information on the feasibility and adaptability of a multi-disciplinary and cross-functional approach to food traceability that generates both commercial value and a safeguard to public health.

Glossary: Traceability Glossary of Terms

Issues, Briefs, and Whites Papers:

- Specifications to Implement a Technology Architecture for Enabling Interoperable Food Traceability (PDF), 2017

Describes characteristics that information systems must possess to enable the implementation of effective and efficient interoperable traceability. Examples of technologies that could enable the architecture to function, along with further considerations and next steps, are also described.