The Natural & Organic Foods Marketplace

Mother Nature moves mainstream as the natural and organic foods market grows worldwide.

Organic, all-natural, additive/preservative-free, non-GMO, free-range, and even kosher. Whatever you call these foods, they are enjoying record-breaking sales as consumers demand cleaner, purer, safer, fresher, and more “close to nature” foods. And along with fortified and functional foods, they’ll represent one of the strongest and most sustainable health-driven markets worldwide for decades to come.

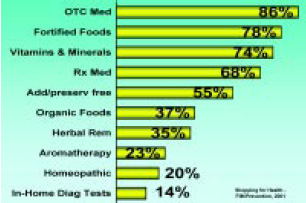

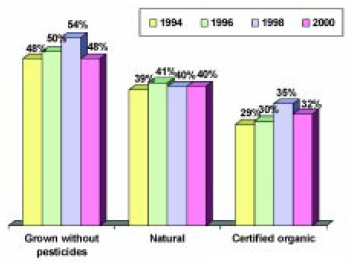

In the United States, more than one-third of supermarket shoppers list organic foods and more than half list additive- and preservative-free foods among the products they use to maintain health (Fig. 1). Since 1994, “certified organic” is the only food claim to show an increase in importance among food shoppers, cited as extremely or very important by 32% (Health-Focus, 2001a). One-quarter of supermarket shoppers actively seek out organic information in stores (FMI/Prevention, 2000). And although almost 60% of consumers are not yet organic users, they say they’re willing to try them (Hartman Group, 2000)!

In the United States, more than one-third of supermarket shoppers list organic foods and more than half list additive- and preservative-free foods among the products they use to maintain health (Fig. 1). Since 1994, “certified organic” is the only food claim to show an increase in importance among food shoppers, cited as extremely or very important by 32% (Health-Focus, 2001a). One-quarter of supermarket shoppers actively seek out organic information in stores (FMI/Prevention, 2000). And although almost 60% of consumers are not yet organic users, they say they’re willing to try them (Hartman Group, 2000)!

Full implementation of the Organic Foods Production Act of 1990 is expected to inspire confidence in the content and quality of organic foods and help calm consumer “label claim” confusion. Rules for organic production, processing, labeling, etc., were finalized in December 2000, and businesses must be in compliance by October 2002 (USDA, 2000). Federal standards will set a level playing field for U.S. food marketers, eliminate the burden of coping with state-by-state directives, and open lucrative international markets. The foray of large food processors into the natural foods marketplace will result in more natural food choices, better prices, and improved distribution and quality. Last, with a showcase for these premium-priced products in mind, the supermarket industry has a national Whole Health Program well underway, establishing a nationwide network of naturally oriented in-store Whole Health Centers, consumer- education display areas, and health-screening programs—sure to keep natural products top-of-mind and excite customer expectations (GMDC, 1998).

With the term “natural” still hampered by consumer, processing, and regulatory controversies—it has not yet been defined by the Food and Drug Administration—it is likely that “organic” products will begin to dominate the natural food and beverage arena. At the same time, the desire for pure and natural will generate a new series of premium products and powerful descriptors, from free-range and farm-raised to classics like kosher and organic combined. No longer confined to just pockets of the U.S. population, large-scale organic consumption will clearly influence the way in which manufacturers, distributors, and retailers develop and process products for tomorrow’s health products marketplace. The following discussion is designed to provide a more in-depth understanding of opportunities in and drivers of the natural products arena.

Au Naturel is Big Business

Au Naturel is Big Business

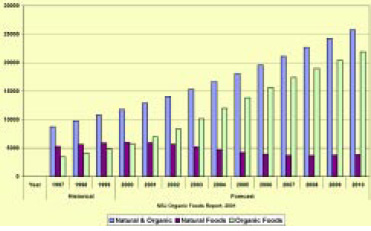

The U.S. natural products marketplace—foods, beverages, supplements, and personal care items—topped $32 billion in 2000 (Spencer, 2001). Nutrition Business Journal (NBJ, 2001) estimated 2001 combined natural and organic food sales at $12.9 billion (up 9.3% over 2000); organic foods at $6.95 billion (up 19.9%); and natural foods at $5.95 billion (down 0.9%, reflecting the switch from natural to organic status for some products; Fig. 2). Nutrition Business Journal’s natural food sales estimates above reflect foods positioned as natural in the labeling, packaging, marketing, or in store promotions; foods sold in the natural/health food channel; foods sold in designated natural sections/kiosks in grocery stores; those with no additives/preservative claims; and those with natural brand and marketing positioning.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Market estimates vary because of individual determinations as to which products are natural; the inclusion of many “food” products such as powders, bars, and beverages in the dietary supplement category because of regulatory requirements; and the difficulty of collecting accurate sales information from small independent stores, co-ups, farmer’s markets, and club stores. For example, Packaged Facts (2000) estimated organic sales at $7.8 billion and Datamonitor (2001a) at $9.4 billion for 2001.

Nutrition Business Journal expects organic food growth to remain in the high teens to twenties for the next five years, with a combined natural/organic category growth rate of 8–10%, a marked contrast to the 2–3% growth for the traditional food industry. The natural/organic food segment is expected to reach $25.8 billion by 2010, with organic foods at $21.9 billion (3.7% of all food industry sales), while natural foods will drop to $3.9 billion, most likely because of abandonment of “natural” claims resulting from regulatory ambiguities and restrictions.

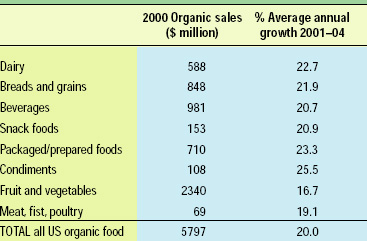

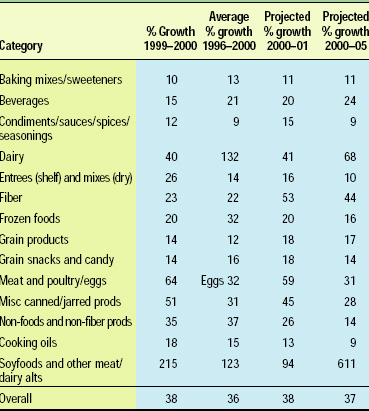

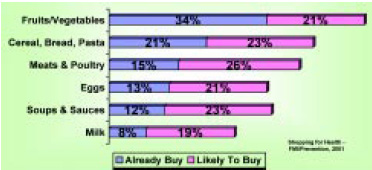

More than nine in ten (92%) of organic users purchase fruits/vegetables, 65% purchase organic packaged goods, and 57% buy both (Hartman Group, 2001). The largest organic market is fresh produce at $2.3 billion (Table 1). In the past six months, 42% of supermarket shoppers bought some type of organic food, and an additional 19–26% shoppers said they would buy each category if sold in their grocery store (Fig. 3). Organic manufacturers reported that all food categories grew, from a low of 10% for baking mixes/sweeteners to a high of 215% for soyfoods and meat/dairy alternatives (Table 2). Manufacturers expect double-digit sales growth for 2001 and predict the strongest increases in the following categories: soyfoods and meat/ dairy alternatives (up 94%), meat and poultry/eggs (up 59%), fiber (up 53%), canned/jarred products (up 45%), and dairy (up 41%) (Table 2).

More than nine in ten (92%) of organic users purchase fruits/vegetables, 65% purchase organic packaged goods, and 57% buy both (Hartman Group, 2001). The largest organic market is fresh produce at $2.3 billion (Table 1). In the past six months, 42% of supermarket shoppers bought some type of organic food, and an additional 19–26% shoppers said they would buy each category if sold in their grocery store (Fig. 3). Organic manufacturers reported that all food categories grew, from a low of 10% for baking mixes/sweeteners to a high of 215% for soyfoods and meat/dairy alternatives (Table 2). Manufacturers expect double-digit sales growth for 2001 and predict the strongest increases in the following categories: soyfoods and meat/ dairy alternatives (up 94%), meat and poultry/eggs (up 59%), fiber (up 53%), canned/jarred products (up 45%), and dairy (up 41%) (Table 2).

Organic and natural foods are quickly moving into the mass market! Of organic users, more than half (53%) now buy organic food at their supermarket, 26% at farmers’ markets, 20% in small health food stores, and 19% in large health/natural food supermarkets (up 13% last year) (FMI/Prevention, 2001).

Grocery/supermarket is the largest channel in terms of sales, representing 62% of overall volume. Discounters, such as Wal-Mart and Costco, have jumped from 1% of sales in 1999 to 13% in 2000 (Hartman Group, 2001). Consumers shop at mass channels because of price, habit, selection, and convenience. Health food stores (11% of sales in 2000) are selected for their knowledgeable salespeople and the belief that these stores genuinely care about their personal health and wellness.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Manufacturers of dairy, frozen foods, soyfoods, and other meat/dairy alternatives reported greatest success selling in mass-market grocery stores. Beverages; condiments, sauces, and seasonings; shelf-stable entrees; dry mixes; and oils were most likely to be sold though natural/ health food stores (OTA, 2001). Not surprisingly, the steady stream of new organic products continues: 842 in 1998, 783 in 1999, and 844 in 2000. In addition, 1,130 new all-natural and 269 no additive or preservative products appeared last year (GNPD, 2001)!

Consumers Are Going Organic

According to the Natural Marketing Institute’s “2001 Health and Wellness Trends Report” (NMI, 2001), 43% of Americans use organic products, up 10% over the previous year, with 17% reporting using more. Within the general population, NMI classifies 6.6% as new users (less than one year, any frequency); 6.3% core users (more than 3 years and more than once a week), and 4.7% heavy users (more than once a day). Almost half of organic users are age 40 or older and are more likely to have a college degree. Geographically, organic food users are more likely to live on the East or West coasts; 44% live in cities and 22% in small towns. The market is driven by one- and two-member households, although 9% are more likely to have five or more members. Organic users fall within 10% of general population income levels.

Many women who become mothers grow more concerned about using only the purest foods to feed their children and become interested in organic and other natural options. Two-thirds of environmentally concerned Generation X supermarket shoppers consider organic foods very or somewhat important, compared to 58% of Boomers and 56% of Matures (age 65 and older) (FMI/Prevention, 2001). Only one-quarter of Caucasian shoppers place a high priority on organic foods, compared to 37% of African-American and 39% of Hispanic shoppers (FMI/Prevention, 2000).

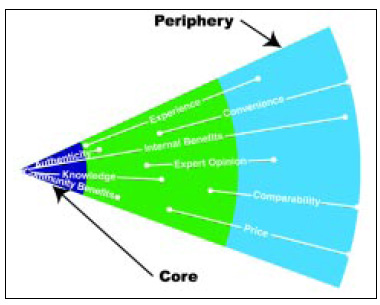

The Hartman Group—which estimates organic use at 48% of all consumers (Hartman Group, 2001)—confirms that users are at various stages of product experimentation and adoption. The Group’s Organic Lifestyle Shopper Study (Hartman Group, 2000) identifies three stages of participation: periphery consumers, who are just slightly involved in organic consumption (59% of households); core consumers, who are highly involved (6%); and mid-level consumers, who continue to gather information about the category while occasionally using organic products (35%) (Fig. 4). Core consumers show two common traits: they believe in the importance of buying organic produce, and they have knowledge and concern about how food affects both personal health and the environment.

The Hartman Group—which estimates organic use at 48% of all consumers (Hartman Group, 2001)—confirms that users are at various stages of product experimentation and adoption. The Group’s Organic Lifestyle Shopper Study (Hartman Group, 2000) identifies three stages of participation: periphery consumers, who are just slightly involved in organic consumption (59% of households); core consumers, who are highly involved (6%); and mid-level consumers, who continue to gather information about the category while occasionally using organic products (35%) (Fig. 4). Core consumers show two common traits: they believe in the importance of buying organic produce, and they have knowledge and concern about how food affects both personal health and the environment.

Price, convenience, comparability, internal benefits, experience, expert opinion, knowledge, community benefits, and authenticity are all key purchase dimensions that affect consumer activity in the world of organics. Depending on which segment a consumer is in, these factors will vary in importance and can be used as influencers to drive potential customers toward heavier consumption.

Market Drivers and Demands

Despite mounting media attention to a wide range of issues—from mad cow disease and import contamination, to environmental runoff, pesticide/antibiotic residues, and GMOs—the two most important factors motivating entry into the natural/organic marketplace are suffering from specific health conditions such as allergies and having children. According to the Hartman Group (2001), Americans opt for organic food and beverages for health/nutrition (66%), taste (38%), food safety (30%), environment (26%), and availability (16%).

• Health and Nutrition. Most users believe organic products contribute to their overall health, rather than associate them with any specific health effect. NMI (2001) reports that prevention is the major driver of non-users to organic products and that the majority of users are seeking long-term health benefits (61%) rather than daily (13%) or short-term (25%). However, new organic users are more likely to desire to “feel better now.” As a result, it is critical for marketers not to over-promise health benefits, as these unrealistic expectations of new users may present problems in conversion and retention of new customers.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

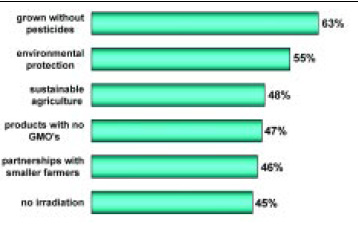

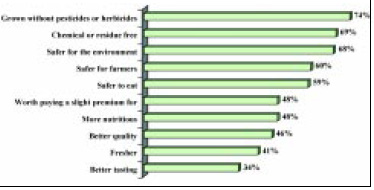

• Chemical Residues. Consumers are looking for ways to reduce personal exposure to chemicals. Nearly two-thirds say that foods grown without pesticides are extremely/very important (Fig. 5). Not surprisingly, they characterize organic foods as being pesticide- and chemical residue–free (Fig. 6). While six in ten consumers agree completely or somewhat that it is important for stores to sell natural foods, 52% felt they should also offer foods with no artificial colors, flavors, or preservatives; 55% no fake fats; 48% no artificial sweeteners; and 45% non-irradiated foods (NMI, 2001). HealthFocus (2001b) found that “grown without pesticides” had even more label appeal than “certified organic” (Fig. 7) and that 44% of consumers were extremely/very concerned about antibiotics/growth hormones in meat/poultry and 43% in milk. More than two-thirds said that natural food is very safe and 58% gave the same rating to organic (CMF&Z, 2000).

• Chemical Residues. Consumers are looking for ways to reduce personal exposure to chemicals. Nearly two-thirds say that foods grown without pesticides are extremely/very important (Fig. 5). Not surprisingly, they characterize organic foods as being pesticide- and chemical residue–free (Fig. 6). While six in ten consumers agree completely or somewhat that it is important for stores to sell natural foods, 52% felt they should also offer foods with no artificial colors, flavors, or preservatives; 55% no fake fats; 48% no artificial sweeteners; and 45% non-irradiated foods (NMI, 2001). HealthFocus (2001b) found that “grown without pesticides” had even more label appeal than “certified organic” (Fig. 7) and that 44% of consumers were extremely/very concerned about antibiotics/growth hormones in meat/poultry and 43% in milk. More than two-thirds said that natural food is very safe and 58% gave the same rating to organic (CMF&Z, 2000).

• GMOs. A large percentage of core consumers seek out organic foods specifically to avoid genetically modified ingredients. Just under half of the general population feels it is extremely or very important to have products that don’t include GMOs (Fig. 5). Not surprisingly, 55% of organic users, 69% of new users, and 63% of core users felt similarly (NMI, 2001). NMI classifies 40% of the general population as “GMO concerned” and points out that the intensity is strong. For the first time, mainstream supermarket shoppers’ general attitudes about agricultural biotechnology are also drifting in a negative direction. Even though barely one in eight shoppers has read or heard a lot about GMOs, most have formed an opinion. Nearly six out of ten have concerns about GMO components in their food; i.e., it does matter to them if there are GMOs present. Women, older shoppers, and those with children are less accepting and more likely to be concerned; 36% felt that genetically engineered foods are dangerous to the environment (FMI/Prevention, 2001).

• The Environment. In 2000, 65% of all shoppers said the environment is extremely/very important to maintaining a healthy, balanced lifestyle. NMI (2000) reported that organic users overall are 31% more concerned about pollution and the environment than the general population. As shown in Fig. 6, the majority of consumers perceive organic food as safer for the environment and for farmers and safer to eat. Not surprisingly, a new series of farm-related issues are moving center stage.

• The Environment. In 2000, 65% of all shoppers said the environment is extremely/very important to maintaining a healthy, balanced lifestyle. NMI (2000) reported that organic users overall are 31% more concerned about pollution and the environment than the general population. As shown in Fig. 6, the majority of consumers perceive organic food as safer for the environment and for farmers and safer to eat. Not surprisingly, a new series of farm-related issues are moving center stage.

Consumers are becoming more concerned about the conditions under which crops or animals are raised, the purity of their water supply, and the potential for contamination by environmental runoff, toxins, and pollutants. More and more producers are benefiting from marketing campaigns that remind consumers that their livestock drink filtered water, are grain/grass fed, or roam free. And the California dairy association reminds customers that beautiful weather makes for happy cows, and therefore better-tasting milk and cheese! Last, organic is perceived as fresher and better tasting, although they are clearly second-tier demands compared to health, nutrition, and safety.

Breaking Barriers and Building Business

According to the Hartman Group (2001), “never considered organic” (41%), “price” (30%) and availability (13%) are the three leading barriers to increased organic food use. Clearly, the price differential will have to decrease to capture true mass-market appeal. Right now, organic consumers still say they are willing to pay a premium because it is a social and health issue for them. However, as time passes, this will be less likely, as was the case with functional and fortified foods. In addition, finding ways of extending shelf life—naturally—and improving taste will be major marketer objectives.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

• Selection and Showcasing in Stores. There is no doubt that greater product selection and heightened visibility in-store will accelerate natural and organic food sales. Although one in four shoppers felt it is very and 60% somewhat important for their ideal grocery store to offer a wide variety of organic foods, only 8% said their stores do an excellent job, and one-third excellent or good (FMI/Prevention, 2001).

Reorganization at retail is essential. Organic food may already be available in stores, but shoppers complain that they can’t find it. Clear signage for the organic section is critical. Most organic food buyers want organic products grouped separately in a special section of the store; 55% prefer their retail outlets to be arranged this way, compared to 37% who want organic versions offered on the same shelf as similar non-organic products (FMI/Prevention, 2001).

Creating a “community” around the products is essential. Ways to do it include emphasizing local connections, supporting health screenings, and tieing into in-store dietitians, cooking classes, and sampling.

• Time to End Confusion. Let’s face it: Flagrant misuse of naturally oriented labeling terms for the past three decades has left consumers wary of the content and contributions of natural, preservative-free, and organic foods. While editorial and advertising are effectively raising the awareness and availability of natural foods, a lack of consumer understanding may make realization of this segment’s potential more difficult. For example, NMI (2001) reports that although 89% of consumers are aware of the term organic, only 47% understand it completely. Likewise, 89% are aware of natural foods and beverages, but only 46% understand them completely. Sustainable agriculture had a 23% awareness level and 15% understanding; and phytonutrients a 12% awareness and 5% understanding.

• Unique Communication Vehicles. It’s important to note, however, that organic and natural food users have unique information-gathering priorities. They are more likely to use books and magazines, nutritionists/dietitians, alternative/complementary health providers, and manufacturers as preferred sources of information than are the general population. In fact, their use of manufacturers as a source of information is more than twice that of consumers overall. Additionally, social networks (i.e., family, friends, coworkers, and peers) have a particularly strong influence on organic product knowledge. Organic consumers consider word-of-mouth and example as strong factors in consumption patterns. Finally, the impact of the media and the types of media that are used vary as a consumer moves from the periphery to the core of the organic world (Hartman Group, 2001).

• Building the Brand. At this point, organic users may be more loyal to the concept of organic than to specific brands. Brand awareness of organic foods is extremely low, although loyalty is high. NMI (2001) analyses reveal that new organic users are driven by national brands; this will make it more difficult to grow the category, with brand awareness at 11% and loyalty at 50%. According to the Hartmann Group, 81% of organic buyers could not think of a specific organic brand name in 2000. These were among the brand names recalled: Amy’s, Barbara’s, Earth’s Best, Edensoy, Health Valley, Nature Valley, Nature’s Own, New Organics, and Sunrise.

• Brand Believability. Will core consumers permit major food marketers—who also make processed food products—to be credible as organic food producers? For some, organic foods are almost “spiritual” in nature, and the thought of major processed food producers offering pure and natural products is “unthinkable.” As a result, clever marketers such as Kraft’s Boca Burger are now offering two lines of meat alternatives in different color packages: one aimed at the natural market and one at the mass retail market. Kellogg’s Morningstar Farms division is also offering a regular meat alternatives line in the traditional green package and a non-GMO version under the Natural Touch brand, which also caries a Morningstar Farms mention—a smart move for future mass market positioning. Interestingly, in the same report (Hartman Group, 2000), several major corporations or brands now owned by major players were recalled: Boca Burger (Kraft), Cascadian Farms (General Mills), Dole, Gerber, Hain (Heinz), Healthy Choice (Con Agra), Heinz, Kraft, Morningstar Farms (Kellogg), and Quaker Oats.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

• Cross-Sell to Other Segments. Other opportunities for natural foods can be realized by analyzing organic users’ use of other categories. For example, organic users are 58% more likely to use herbal products, 34% functional foods, 29% fortified foods, and 23% soy-based products than the general population. Conversely, soy food users are 67% more likely to use organic foods, meal-replacement-drink users 41% more likely, and energy bar customers 37% (NMI, 2001).

Up-and-Coming Opportunities

It’s going to be a whole new natural foods marketplace out there, with multinational giants like Nestlé, Heinz, Quaker Oats, General Mills, Danone, Kellogg, and Kraft attacking the sector through new product development or acquiring/partnering with major brands like Stonyfield Farms, Boca, Hain and Morningstar Farms. Even Coke and PepsiCo’s Tropicana are toying with alternative soy beverages!

Today, organic and natural foods are available in almost every category. For example, leader Amy’s Foods, Petaluma, Calif., offers frozen organic hand-held wraps, stuffed breads, and pocket sandwiches; toaster pastries; skillet meal kits; country pot pies; and other frozen assorted desserts, appetizers, and main course entrees.Florida Crystals, Palm Beach, Fla., offers a premium natural organic cane sugar; Spectrum Naturals, Petaluma, Calif., offers certified organic mayonnaise; and Walnut Acres, Acirca, Inc., has “Certified Organic” soups. And there will be a variety of organic products from now on. The USDA rule permits four labeling categories, making it easier than ever to enter the market: “100% organic,” “organic,” “made with organic” and “organic ingredients only.” Look for major-league action in the following categories:

• Soyfoods Staying Strong. The soyfoods category increased 21.1% in 2000 to $2.77 billion. SoyaTech (2001) projects 20% growth overall in 2001, with some categories, such as cold cereals and soymilk yogurt, growing as much as 75–100%. Soymilk sales grew to over $470 million (up 33%), with refrigerated soymilk in mainstream markets driving the category. Soymilk volume was estimated to be about 1% of fluid milk sales. Meat alternatives grew by nearly 15%, and energy bars with soy nearly 40%. Soyatech reports that 90% of tofu and soymilk companies use some or all organic soybeans for production, up from 75% in 1995. Two big drivers here are GMOs and the lack of a coherent and consistent labeling rule on GMO, and USDA’s organic standard. “Not all soy products can be made organically because their base ingredients such as soy concentrates or isolates cannot be made organically, but those that can be will be and those that can be non-GMO are going that way as well,” reported Soyatech’s Peter Golbitz.

Watch as unique products such as Coca-Cola’s OdwallaMilk (a blend of organic soy, basmati rice, and oat milk), Glaceau Soywater, and Stonyfield Farms O’Soy yogurt gain in appeal.

• Here Come the Kids. With kids’ health quickly becoming a national priority, targeting parents with natural products is good business, and that’s just what clever marketers are doing. Led by Tender Harvest, Earth’s Best, and Well-Fed Baby, sales of organic baby food last year jumped 26% to $240 million (NBJ, 2001). One of the most creative marketers has been Stonyfield Farms, which offers synbiotic regular, soy, and squeezable organic yogurts, Yo-Baby for infants, and Yo-Squeez for kids. Kids’ meals such as Fran’s Healthy Helpings and the entire line of New Organics, Braintree, Mass.’s Richard Scarry’s kid-oriented dinners, beverages, and syrups are coming on strong.

• Premium Priced Meats, Fish, Poultry and Eggs.With consumer concern over the safety of current meat and poultry offerings, organic alternatives are a “no-brainer.” In fact, 13% of supermarket shoppers have already purchased organic meat/poultry despite high prices and limited availability. But from an industry standpoint, it is easier said than done. NBJ (2001) estimates that certified organic livestock is still less than 1% of all livestock production.” While there is demand for prime cuts, there is little use for the others. A more predictable boost to organic meat producers will be the inclusion of organic meats in canned or pre-packed soups, stews, and frozen meals. Cascadian Farms is using organic Petaluma poultry in its prepared organic “bowl meals.” Organic beef sales are estimated at $10–20 million, poultry $10–20 million, and organic eggs $22 million (NBJ, 2001). The subject of organic fish standards has yet to be settled.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

And there’s much more to come. From soy nuts to rice crisps, the virtually untapped savory snack food segment will take a natural turn. Just under 100 new organic snacks were introduced in 2000 (up49%), as well as 133 new snacks carrying “no additives or preservatives” claims (GNPD, 2001). Watch for organic oils, deli items, ketchup, and dairy items galore.

• Pet Foods. And then there are pets, too! With nothing too good for America’s 235 million cats and dogs, the natural pet food aisle is well worth watching.

• Foodservice Opportunities. While chefs are backing the non-GMO movement and featuring organic greens and local natural specialty ingredients on high-end menus, the organic restaurant movement has been confined to the high-end segment. In 2000, just over half of table-service restaurants with an average check of $25 or more offered organic items, and nearly eight out of ten offered locally grown produce (Table 3). Most likely because of limited availability, higher cost, and questions about product quality and consistency, manufacturers surveyed by OTA (2001) reported only 2% of their sales through the foodservice channel last year.

• Foodservice Opportunities. While chefs are backing the non-GMO movement and featuring organic greens and local natural specialty ingredients on high-end menus, the organic restaurant movement has been confined to the high-end segment. In 2000, just over half of table-service restaurants with an average check of $25 or more offered organic items, and nearly eight out of ten offered locally grown produce (Table 3). Most likely because of limited availability, higher cost, and questions about product quality and consistency, manufacturers surveyed by OTA (2001) reported only 2% of their sales through the foodservice channel last year.

According to Chain Account Menu Survey’s Trendspotter 2001 database, which tracks menus within a designated semgent of high-end restaurants known to historically be trendsetters, only 4 menu mentions out of 4,268 were of organic ingredients What appears on menus are organic style descriptions like “local spring lettuce,” “free-range chicken,” and “horse-drawn farm lettuce.” They also report that of the nation’s top 200 chain restaurants, not one mentioned organic on its regular menus. But it’s only a matter of time! Foodservice customers are increasingly interested in how products are grown and processed. In response, many operators will likely expand the number of organic menu items and ingredients longer term.

• International Opportunities. Organic foods and beverages are part of the $144-billion nutrition industry tracked by Nutrition Business Journal. Organic and natural food sales worldwide contributed $30.4 billion (21%) in 2001. Organic and natural food sales in 2000 were led by Europe ($12.6 billion) and the U.S. ($11.8 billion), followed by Japan ($3.2 billion). Organic foods represent 63% of the total natural/organic market worldwide at $19.1 billion. Some nations of Europe have organic sales as high as 80–85% of the total natural marketplace as the term “natural” or sale from “natural food stores” is not highly significant. The U.S., in contrast, is roughly 50%.

SOL (2001), which estimates the international organic foods market slightly higher at $19.7 billion, reports that the U.S. was the largest individual market. Sales in Western Europe totaled $9 billion. Within Europe, Germany was the largest market with retail sales of $2.5 billion in 2000, followed by France ($1.23 billion), Italy, a strong exporter ($1.1 billion), and Britain ($900 million).

Annual per capita spending tells a different story, led by Denmark with $56.60, Switzerland $49.30, the Netherlands $22.58, and Germany $21.95 (Organic Insights, 1998). Datamonitor (2001b) predicts that UK shoppers will become the largest consumers of organic food in 2005, with per capita spending of $69.5, well above the average of $42.

For the past ten years, the European market has averaged 25% annual growth. Global market growth for organic foods is forecast to be 15–20% in 2000–05, and 10–15% in 2005–10. The highest growth rates are forecast to be in parts of Europe for 2001–03, with North America catching up in 2004–05. Other emerging markets will exhibit significantly higher growth rates in a series of years as markets emerge. In some European markets, annual growth for organics is exceeding 40–50%, and short-term forecasts are calling for growth in the 20–40% range.

Unlike the U.S. market, the European market is characterized by a political will to grow organic agriculture, and this has been accelerated by serious food scares. Consumers are more motivated by environment and fair-trade issues. There is grassroots opposition to agricultural biotechnology, anti-GMO coverage in the popular press, and a sustained, large-scale commitment to organic foods by the supermarket chains responsible for the vast majority of food sales. In the UK and Germany, for example, most major grocery chains have made much more significant commitments to selling and manufacturing organic foods than their counterparts in the U.S.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

A Strong Future

Few healthy-food markets have been stronger longer than organic. Sales have been nearly doubling every three years, and the future market potential is awesome. According to Roper Starch Worldwide (2001), half of Americans say they will be using more organics in their home within the next five years, and 40% say organic products will be an increasing part of their family’s diet within the next year (2001). Around two-thirds of organic skeptics and non-believers say that USDA’s new organic standards will increase their confidence in organic foods. The main reason that consumers give for not buying organic and natural foods are the cost premium, lack of selection or availability, and poor quality/shelf life—all problems easily remedied by the entry of major marketers’ “know-how” and distribution systems.

At the same time, organic farmland in the U.S. has expanded to an estimated 2 million acres in 2000, up from 1.35 million in 1997 (NBJ, 2001). Consolidation has created a series of mega organic farms that are producing an increasingly large proportion of organic raw materials. Clearly, more organic and non-GMO ingredient options will make entrance into the market for manufacturers, ingredient suppliers, and consumers more cost effective.

Nearly eight in ten consumers are motivated to go organic because of fears over food safety, and six in ten who are relatively healthy eaters say it fits into their lifestyle well—so the future looks strong. The Sloan Trends and Solutions’ TrendSense™ market projection model (Sloan, 2001a) shows both the organic and natural food markets continuing to grow at unprecedented rates. In addition, in the Early Warning and Trend Tracking media system (Sloan, 2001b), the terms natural and organic rank in the third-highest tier of media coverage—“Very Strong Media Coverage”— along with fortified foods, immunity, mental acuity, and children’s health. More important, 88% of media coverage of natural is positive; 95% for organic.

And there’s plenty of room for growth. New regulations will open up more organic exports to the UK and Japan. Environmentally sensitive trendsetting chefs—now being schooled in sustainable agriculture during culinary training—will open up the virtually untapped mid- and lower-end foodservice markets. Wild Oats Market is promoting “5-A-Day” the organic way! And with retail markups on such products almost double those of traditional grocery store items, retailers are going to make more space for these products on their shelves in the years to come!

by A. Elizabeth Sloan,

Contributing Editor

The author is President, Sloan Trends & Solutions, Inc., P.O. Box 461149, Escondido, CA 92046 ([email protected]).

References

Chain Account. 2001. Trendsetter survey section of the Chain Account Menu Survey Report, Wheaton, Ill. ([email protected]).

CMF&Z. 2000. Food issues survey, CMF&Z Public Relations, Des Moines, Iowa.

Datamonitor. 2001a. U.S. organics report. Datamonitor for the Organic Trade Assn., New York, N.Y. (www.datamonitor.com).

Datamonitor. 2001b. The European market for organic foods. London, UK.

FMI/Prevention. 2001. Shopping for health 2001: Reaching out to the whole health consumer. Food Mktg. Inst., Washington, D.C. (www.fmi.org), Prevention, Emmaus, Pa. (www.prevention.com).

FMI/Prevention. 2000. Shopping for health 2000: Selfcare needs and whole health solutions. Food Mktg. Inst., Washington, D.C. (www.fmi.org), Prevention, Emmaus, Pa. (www.prevention.com).

GMDC/FMI. 1998. Best practices case studies: Whole health. General Merchandise Distributors Council and Food Mktg. Inst., Washington, D.C.

GNPD. 2001. Data from New Product News database. Mintel, Chicago, Ill. (www.gnpd.com).

Hartman Group. 2000. Organic lifestyle shopper study: Mapping the journey of organic consumers, Fall. Bellevue, Wash. (www.hartman-group.com).

Hartman Group. 2001. Healthy living: Organic and natural products organic lifestyle study, Spring. Bellevue, Wash. (www.hartman-group.com).

HealthFocus. 2001a. What do consumers want from organics? HealthFocus consumer trends report. Atlanta, Ga. (www.healthfocus.net).

HealthFocus. 2001b. 2001 HealthFocus trends report. Atlanta, Ga. (www.healthfocus.net).

NBJ. 2001b. Organic foods report 2001. Nutrition Business J., San Diego, Calif. (www.nutritionbusiness.com).

NMI. 2001. Health and wellness trends report. Natural Marketing Inst. Harleysville, Pa. (www.nmisolutions.com).

NRA. 2000. Tableservice restaurant trends survey. Natl. Restaurant Assn., Washington, D.C. (www.restaurant.org).

Organic Insights. 2000. U.S. Organic Trade Association’s export study for U.S. organic products to Asia and Europe. Greenfield, Maine.

OTA. 2001. 2001 OTA manufacturers’ market survey. Organic Trade Assn., Greenfield, ME. (www.ota.com).

Packaged Facts. 2000. The U.S. organic food market. Market Research, New York, N.Y. (www.marketresearch.com).

Roper Starch Worldwide. 2001. Walnut Acres Certified Organic Future survey. New York, N.Y.

Sloan. 2001a. Proprietary data from TrendSense Predictive Trend Tracking Report, July. Sloan Trends & Solutions, Inc., Escondido, Calif.

Sloan. 2001b. Proprietary data from Early Warning and Trend Tracking System, Sloan Trends & Solutions, Inc., Escondido, Calif.

Soyatech. 2001. Soyfoods: The U.S. market 2001. Produced in association with SPINS and Arthur D. Little. Bar Harbor, Maine. (www.soyatech.com).

SOL. 2001. Foundation, ecology, and agriculture. Stiftung Okologie & Landbau. Intl. Federation of Organic Agriculture, Geneva, Switzerland.

USDA. 2000. National Organic Program; Final rule. Agricultural Mktg. Service, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Fed. Reg. 65: 80547-80596.

Spencer, M.T. 2001. Natural products sales top $32B. Natural Foods Merchandiser, June, p. 1.

Edited by Neil H. Mermelstein,

Editor