Improving the Success of Functional Foods

Understanding how functional foods are defined and regulated can increase chances of success in the marketplace.

The topic of functional foods is well documented in the literature. However, information on functional foods in publications on food science, nutrition, dietetics, health, and marketing is often vague and sometimes inconsistent, and as a result, is of limited value to the food science professional.

This ambiguity reflects the different focus of each discipline, as well as the complexity of the subject matter. Although some advances have been made, further scientifically sound in-vitro, animal, and epidemiological studies and clinical trials are needed to provide evidence to clarify the issues in question regarding functional food definition and categorization, chemical and physical testing, safety and efficacy testing, nutrient bioavailability and interactions, and formulation issues. Data from these studies will permit precise safety, quality, and regulatory standards, as well as explicit marketing claims.

Clearly, much of the confusion surrounding functional foods on these points is based on their ability to fit into multiple categories. For example, in the current regulatory environment, functional foods may be classified as conventional foods, food additives, foods for special dietary use, dietary supplements, or medical foods. The classification used to define a functional food depends on the manufacturer’s chosen market positioning and label claims.

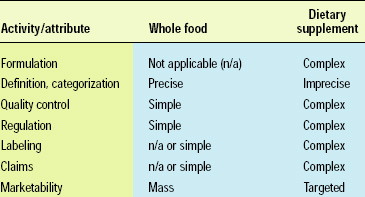

Functional foods exist on a continuum ranging from whole foods to dietary supplements. Whole foods, such as fruits and vegetables, are the simplest functional foods, in terms of definition and categorization, quality control, regulation, and marketing. Other foods are more complex and challenging to define and categorize; their quality control and regulation are more expensive and complicated; and their marketing claims require additional substantiation. More-complex functional foods, such as specialized dietary supplements, target a small segment of the population and are therefore less relevant or marketable to the mass consumer (Table 1).

Definition and Categorization

Currently, there is no precise, universally accepted definition of functional foods. The term is defined and used differently in various countries. As stated by NoSeong and Jukes (2001), “Overlap and discrepancies exist for EU, USA, Japan, WHO, and Codex Alimentarius definitions and terms for functional, dietetic, medical, fortified or enriched foods, dietary supplements, health foods, nutraceuticals, and novel, designer, and pharma-foods.”

Several organizations have proposed definitions for the category of functional foods. Japan first defined functional foods in the mid-1980s as “processed foods containing ingredients that aid specific bodily functions in addition to being nutritious.” The International Food Information Council defines functional foods as “foods that provide health benefits beyond basic nutrition” (IFIC, 1998). The International Life Sciences Institute of North America has a similar definition: “foods that, by virtue of physiologically active food components, provide health benefits beyond basic nutrition” (Clydesdale, 1999).

The Food and Nutrition Board (1994) limits functional foods to “those in which the concentrations of one or more food constituents have been manipulated to enhance their contributions to a healthful diet.” The American Dietetic Association defines functional foods as inclusive of the entire range of whole foods and fortified, enriched, or enhanced foods (ADA, 1999). ADA further states that “the term ‘functional’ implies that the food has some identified value leading to health benefits, including reduced risk for disease, for the person consuming it.”

According to these latter definitions, whole foods represent the simplest example of a functional food. Broccoli, carrots, and tomatoes are considered functional foods because of their high contents of physiologically active components (sulforaphane, beta-carotene, and lycopene, respectively). The General Mills breakfast cereal Cheerios is also a functional food, as a result of constituent soluble fiber which is efficacious in reducing serum cholesterol levels. Modified foods—e.g., foods fortified with nutrients or supplemented with phytochemicals or botanicals—are also on the functional foods continuum, as are innovative food biotechnology products and dietary supplements.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Despite these somewhat clear definitions and categories, and precise regulations for the endpoints of the continuum, the remainder of the range between whole foods and dietary supplements remains somewhat gray. While some functional foods are easy to differentiate from a dietary supplement or medical food, there is tremendous overlap in many categories. The classification used to define a functional food is often dependent on the selected market positioning and label claims.

There are numerous examples where functional foods may be inaccurately perceived. One example is a table spread containing ingredients that reduce serum cholesterol levels; this product may be marketed as a food or a dietary supplement. Another example is a dietary calcium supplement. Such supplements are efficacious in improving the dietary intake of calcium, an important dietary ingredient for promoting bone health and preventing osteoporosis. As a dietary supplement, calcium is regulated by the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA). However, recently it has been formulated in a confectionery chew form. Thus, it appears to be a food product, but is not purported to be a food, nor does the label state it as such.

Also of note is the attempted labeling of a product as a dietary supplement when it actually contains a drug, which is illegal. An example is the dietary supplement containing ephedrine (ephedra) marketed for weight loss. This substance has been linked to numerous adverse health effects (e.g., hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, etc.) and even death. In February, the Food and Drug Administration proposed to require strong warning labels for products containing ephedra.

It has been suggested that in view of these and other complex relationships, functional foods may be better controlled by alternative approaches such as health claims (NoSeong and Jukes, 2001).

Quality Control

One challenge posed by functional foods is quality control. While drugs are regulated by strict standards in the industry, few quality control systems monitor functional foods and ingredients used in dietary supplements. Currently, these products must be evaluated individually, and numerous factors must be considered to determine if a product is of high quality.

These factors include rigorous auditing of a company’s facility and locations where the product is manufactured, warehoused, packaged, and tested to ensure compliance with regulations; a complete review of a manufacturer’s product and production records to validate compliance with FDA regulations for foods or supplements and with U.S. Pharmacopoeia standards, if applicable; analytical, microbiological, physical, and sensory testing; and testing of potency, bioavailability, weight variability, product workmanship, package workmanship, labeling, and net contents.

In addition to traditional quality tests ensuring that the nutrient/factor is present for the shelf life of the product, tests are also required to ensure retention of the functional health characteristics, i.e., that the product retains efficacy. For example, in the case of probiotics, viability is an issue, but other criteria are also critical, including adhesion characterization, strain stability, etc. Thus, quality assurance should include additional tests, including in-vitro tests, molecular techniques, and others (Tuomola et al., 2001). Independent testing is also needed to validate the consistent quantity of the ingredient. Overall, the lack of standardization is a critical issue influencing the quality of commercial nutraceutical dosage forms. Adebowale et al. (2001) describe this problem with specific reference to chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine.

There is an assumption that functional foods or ingredients are of high quality if manufactured by established reputable companies. However, there is no mechanism to distinguish between companies that produce high-quality products and those that do not.

FDA’s proposed Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs) may resolve these issues, at least with respect to dietary supplements.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Regulation

Currently, the regulation of functional foods is inexplicit. Research and regulation focused on quality control standards are necessary to ensure consistency, efficacy, and safety of functional foods (Adebowale et al., 2001). Continued collaboration of FDA, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the food industry, health care professionals, and consumers is also requisite (ADA, 1999).

Functional foods are undefined under existing United States food regulations. “Since functional foods do not possess a legal definition, they do not have straight-forward regulations,” according to Platzman (1999). “The government regulates different categories of functional foods differently. For example, new foods and drugs must always have FDA approval; in comparison, dietary supplements are lightly regulated.” Complicating the issue is that, as mentioned above, functional foods or components may be placed into multiple existing categories—conventional foods, food additives dietary supplements, medical foods, and foods for special dietary use.

There are two key issues regarding the regulation of functional foods: how well federal agencies and regulations are ensuring the safety of functional foods and dietary supplements, and how accurate companies are in stating health-related claims on product labels and in advertising.

Functional foods are covered by the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act and regulations from FDA. A functional food or nutraceutical that is a food and not a supplement must be in compliance as a food; i.e., all ingredients must be either an approved food additive or a Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) substance. This requirement does not apply to dietary supplements. The Nutrition Labeling and Education Act permits specific health and nutrient content claims for a food, but the food must be in accordance with FDA regulations. The health and nutrient content claims permitted for functional foods are specified in Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations. The FDA Modernization Act provides an additional process for manufacturers to apply health claims based on statements from certain federal scientific organizations.

Dietary supplements are regulated by FDA under DSHEA, which defines a dietary supplement as a product added to the total diet. New dietary ingredients in supplements are exempted from requirements that apply to food additives or GRAS-listed substances. DSHEA permits use of dietary supplement health claims without prior FDA approval, assuming that the product is safe and the claims are supported by a recognized scientific body. DSHEA also permits structure/function claims without prior FDA authorization. FDA requires a statement on the label that the claims have not been evaluated by FDA.

Manufacturers may also market functional foods by disseminating product information through advertising, which is regulated by FTC. The FTC standard for advertising claims of diet–disease relationships is less stringent than FDA’s standards for food labeling. Hence, the potential exists for an advertising medium to permit mention of an association between a food product and disease prevention. For example, a company that manufactures a tomato product—a dietary source of the carotenoid lycopene—may refer to the health benefits of lycopene, an antioxidant associated with reduced risk of certain types of cancer, on its Web site.

In March 2003, FDA proposed to establish a rule entitled “Current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) in Manufacturing, Packing, or Holding Dietary Ingredients and Dietary Supplements.” These new cGMPs may clarify these issues and lead to improvements in quality control and labeling of some functional foods that are marketed as supplements. The cGMPs will require manufacturers to evaluate the identity, purity, quality, strength, and composition of all dietary supplement products. However, there is some dissention in the industry as to whether the new cGMPs will finally provide the much-needed high-quality, industry-wide standards for dietary supplements, or whether they are still not stringent enough (Johnsen, 2003).

Marketing Claims

Health claims for functional foods is a controversial and multifaceted issue that is being debated by food regulators globally. Advocates assert that health claims are a legitimate nutrition education tool that instructs consumers about the health benefits of functional food products and may reduce health-care costs. Conversely, opponents state that the so-called “magic bullets” are not important relative to the total diet. “Moreover, they argue that health claims will enable manufacturers to engage in marketing ‘hyperbole’ and essentially blur the distinction between food and drugs,” according to Lawrence and Rayner (1998). Additionally, as more and more people consume functional foods and dietary supplements, the issues of safety and efficacy in relation to the long-term health effects and benefits must be considered. Of particular importance is the potential for adverse nutrient–nutrient and drug–nutrient interactions.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

It is critical for the food science professional to realize the significance of the messages sent by health claims on functional foods. As Clydesdale (1997) stated, “Health claims for functional foods influence consumer behavior and potentially affect public health. In an increasingly global economy, health claims for functional foods should meet internationally agreed upon scientific criteria.”

Explicit marketing claims must be based on scientific evidence that the functional food is effective in general and at the level of the serving size; measurable health benefits from the functional ingredient; well-designed and controlled human clinical intervention trials; and studies published in peer-reviewed journals (Hasler et al., 2001).

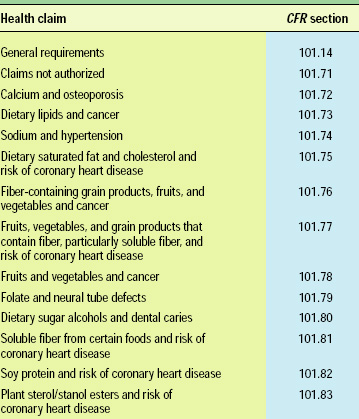

Currently, 12 specific health claims for foods (Table 2) have been approved by FDA as a result of scientific evidence showing significant agreement to support the claim (FDA, 2002a). For all other functional ingredients, there is no regulation of the levels required or health claims permitted.

Still, some functional food manufacturers attempt to market products with other claims. For example, a seven-grain herb bread manufactured by a U.S. company was recently deemed misbranded and noncompliant because the label on the immediate packaging contained an unauthorized health claim: “Antioxidants help prevent . . . degenerative diseases of all types.”

In the future, FDA may permit manufacturers to make certain health claims for foods even though the stated benefits may still be of scientific debate. Concurrently, FDA reportedly intends to increase enforcement against misleading health claims by the diet supplement industry. Under the change, companies may submit qualified health claims for conventional foods based on the “weight of scientific evidence,” which represents an easing of the requirement of consensus backed by “totality of publicly available scientific evidence” (FDA, 2002b). For example, under the change, FDA may permit submission of a health claim suggesting that foods containing omega-3 fatty acids present in some fish products may reduce the risk of coronary heart disease. Also, FDA will apply the “reasonable consumer” standard in the evaluation of food labeling claims (FDA, 2002b).

It is evident that functional food label claims, including health, nutrient content, and structure/function statements, must be valid, explicit, and based on significant scientific consensus. As noted by ADA (1999), “This will protect consumers, provide information and scientifically-sound label claims that will improve food selections and potentially advance wellness. This approach will provide the food industry with specific guidelines that, in turn, will direct research and development for future functional foods.”

Increasing the Chances of Success

Functional foods are assuming an increasingly prominent role in the health and well-being of consumers. The research and development of innovative functional food products is increasing exponentially, particularly for those products that have the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality. As more and more scientific data are obtained, correlating the physiologically active elements of phytochemical (plant) and zoochemical (animal) sources to overall improved health and prevention of disease, these functional foods will continue to dominate the attention of consumers and industry alike. With all of the challenges and opportunities that still lie ahead, food scientists who fully understand all aspects of functional foods, from definition/categorization and quality control to regulation and health claims, will be able to create functional foods with the highest probability of success in the marketplace.

by Laurie A. Lucchina

The author, a Registered Dietitian and Professional Member of IFT, is Director of Technical Services, Shuster Laboratories, Inc., 85 John Rd., Canton, MA 02021.

References

Adebowale, A.O., ZhongMing, L., and Eddington, N.D. 1999. Nutraceuticals, A call for quality control of delivery systems: A case study with chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine. J. Nutraceuticals, Functional, and Medical Foods 2(2): 15-30.

ADA. 1999. Functional foods: Position of the ADA. Am. Dietetic Assn. J. Am. Diet. Assn. 99: 1278-1285.

Clydesdale, F.M. 1997. A proposal for the establishment of scientific criteria for health claims for functional foods. Nutr. Rev. 55: 413-22.

Clydesdale, F.M. 1999. ILSI North America food component reports. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 39: 203-316.

FDA. 2002a. Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21. Food and Drugs. Food Labeling. Chap. 1. Part 101. Food and Drug Admin. U.S. Govt. Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

FDA. 2002b. Guidance for industry. Qualified health claims in the labeling of conventional foods and dietary supplements. Food and Drug Admin., Washington, D.C.

Food and Nutrition Board. 1994. Summary and conclusions. In “Opportunities in the Nutrition and Food Sciences: Research Challenges and the Next Generation of Investigators,” ed. P.R. Thomas and R. Earl, pp. 1-14. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C.

Hasler, C., Moag-Stahlberg, A., Webb, D., and Hudnall, M. 2001. How to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and quality of functional foods and their ingredients. J. Am. Diet. Assn. 101: 733-736.

IFIC. 1998. Backgrounder: Functional foods. In “Food Insight Media Guide.” Intl. Food Information Council Foundation, Washington, D.C.

Johnsen, M. 2003. GMPs could boost OTC credibility, but do proposals go far enough? Drug Store News 5: 13.

Lawrence, M. and Rayner, M. 1998. Functional foods and health claims: A public health policy perspective. Public Health Nutr. 1(2): 75-82.

NoSeong, K. and Jukes, D.J. 2001. Functional foods II: The impact on current regulatory terminology. Food Control 12(2): 109-17.

Platzman, A. 1999. Functional foods: Figuring out the facts. Food Prod. Design 11: 32-62.

Tuomola E., Crittenden, R., Playne, M., Isolauri, E., and Salminen, S. 2001. Quality assurance criteria for probiotic bacteria. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 73(2S): 393S-398S.