Reducing Sodium A European Perspective

European attitudes and regulations regarding sodium in foods pose challenges for the food industry.

Research shows that consumers are actively trying to reduce the amount of salt in their diet. In a poll carried out by Research Surveys of Great Britain on behalf of the United Kingdom’s Food Standards Agency (FSA, 2005a), 32% of the respondents claimed to be making a special effort to lower salt intake. Manufacturers are set to reap the rich potential rewards of this trend. This article will review current European attitudes, regulations, and responses to the low-sodium debate and challenges for the food industry.

The Oldest Additive

Salt is the world’s most-established food additive. It is widely used as a seasoning—it makes bland foods such as bread and pasta more palatable and enhances natural flavors. Humans and other mammals have always exhibited an inherent craving for salt—perhaps it is this which makes the salty taste in foods so popular. Salt can also improve texture and mouthfeel in processed foods, making them thicker and less watery, and aid in color development.

It can also be used as a preservative. In fact, salt curing is one of the earliest recognized forms of food preservation for meat, -sh, and vegetables. Many foods require salt as part of the production process—e.g., it acts as a microbial control agent in sausages and cheeses. However, much of the salt hidden in food acts to improve palatability of processed foods and significantly exceeds the amount of salt required for processing. In fact, it is estimated that 75% of the salt we consume is hidden in processed foods (WHO, 2002).

Health Concerns & European Legislation

Although sodium is required for normal human body functions, salt consumption levels in Europe significantly exceed nutritional requirements. The body only needs around 1 g of salt per day to function, but actual intake is significantly higher in many Western European countries. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA, 2005a) estimates that the average daily intake is 3–5 g of sodium (8–11 g of salt) throughout Europe. These findings have encouraged further debate on the need to reduce salt intake for health purposes.

Sustained media and government campaigns have made consumers well aware of the potential health risks surrounding high sodium intake, most notably hypertension. A recent study in the UK (FSA, 2005b) showed that since 2004 there has been a 31% increase in number of people who look at the sodium content on food labels and a 27% increase in number of people who say that sodium levels in food affect their buying choices.

Scientific studies, such as the Intersalt (1988) study, have led to public health campaigns and government action to highlight potential health risks caused by high sodium consumption. High sodium intake encourages the body to retain water, which can cause hypertension, a significant risk factor in the development of heart disease and strokes. Cardiovascular disease is recognized as a major cause of morbidity and mortality in Europe. The British Medical Research Council claims that a reduction of daily salt intake to 6 g from the average British intake of 9.5 g could lead to a 13% reduction in stroke and a 10% decrease in heart disease (He and MacGregor, 2004).

Following these studies, many national and international bodies have published advisory guidelines for daily salt intake; e.g., the World Health Organization recommends restricting daily salt intake to 5 g (WHO/FAO, 2005). However, because of the huge cultural diversity and variation in dietary patterns across Europe—France recommends an upper salt intake limit of 8 g; the UK, Germany, and Denmark 6 g; Sweden 5.6 g; Greece 5 g; and Finland 3–5 g—it has been difficult to set one consistent figure. In addition, EFSA found in April 2005 that there was not sufficient data to establish an upper limit on sodium intake from dietary sources (EFSA, 2005b). Therefore, it seems that despite many national recommendations for healthy levels of salt intake, legislative action on a pan-European level may be some way off.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Despite these differences, a number of European Union countries and Norway agreed to a common resolution in 2004 to recognize that salt intake is a important public health concern and to work together on solutions to decrease salt content within the food industry (FSA, 2004). This agreement included a commitment to work together to promote harmonization of European rules for salt labeling on food.

There is currently no pan-European legislation on food labeling. In the UK, food manufacturers are required to state the sodium content of the product but not the salt content. Research from the National Consumer Council in Britain has shown that consumers do not have a strong understanding that sodium content must be multiplied by 2.5 to obtain the true salt content of food (Gibb, 2004b). Salt is listed on some but not all food labels. To increase consumer awareness of salt intake levels, however, some UK retailers such as the Co-op food chain are now publishing salt and sodium levels on all their own-brand products (Gibb, 2004a). This is seen as a key step in helping to reduce dietary intake of salt.

Pressure from the media, action groups, government-recommended targets, and consumer preferences has forced food manufacturers to take action to reduce the salt content of their products. They are increasingly exploring alternatives to salt in the production process and creating more reduced-sodium foods. In the UK, for example, more than 60 companies involved in food production—including retailers such as Tesco, Sainsbury’s, and Asda—support the British government’s proposal to reduce salt in diets by 2010 (FSA, 2006).

A record 200 of low-/reduced-sodium products were introduced in Europe in 2005, compared to 86 in 2002 (Mintel, 2002, 2005)—the top three food sectors were savory (37%), bakery (18%), and dairy (11%), and the top three countries were the UK (32%), Spain (15%), and Finland (11%).

Salt Alternatives & Taste Enhancers

Food manufacturers are faced with the dilemma of how to reduce the salt content of foods without losing their palatability. While trends indicate that consumers are increasingly proactive in opting for the healthier solution when it comes to food, taste remains the most critical factor for consumers when deciding whether to buy a product.

To reduce salt content, some manufacturers are simply choosing to add less salt to their products without replacing the taste. However, manufacturers are generally wary of alienating customers by losing their product’s taste and are looking for alternative technologies. Consensus Action on Salt & Health, a UK group of specialists concerned with salt and its effects on health, claims that a 10–25% reduction in salt content cannot be detected by human salt-taste receptors (CASH, 2006).

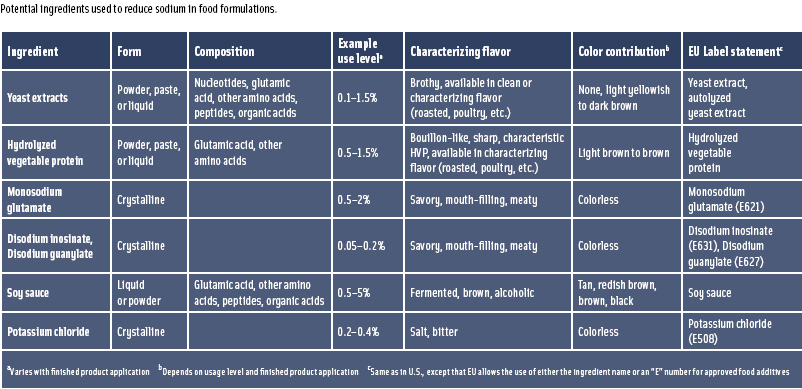

Various alternatives are available, including potassium chloride and taste enhancers (see table on page 28).

Various alternatives are available, including potassium chloride and taste enhancers (see table on page 28).

• Potassium chloride as a replacement for sodium chloride is one of the most common ways to reduce salt content. It helps to maintain a salty taste and can reduce salt content by 25% without losing the desired salty taste (Fletcher, 2005). However, it often leaves a bitter aftertaste and contributes to off-notes that some consumers find unpleasant. Therefore, more manufacturers are turning to taste enhancers.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Taste enhancers work by activating receptors in the mouth and throat, which helps to compensate for the salt reduction. Taste enhancers particularly elicit the “umami” taste receptor, improving balance and taste perception in food.

The term umami comes from the Japanese word for flavorful. In 1908, Professor Ikeda discovered that a form of seaweed was rich in glutamic acid, which had its own distinctive taste that he proposed as umami. Umami was officially recognized as the fifth taste in the 1980s. In products such as low-sodium foods where imbalances are so great that reformulation is required, umami can be used to impart a fuller flavor with less sodium.

Umami-inducing compounds exist in nearly every food but in varying proportions. Some foods, such as peas and tomatoes, naturally contain more glutamic acid. Other foods, such as shitake mushrooms and tuna, naturally contain other components, such as nucleotides, that work synergistically with glutamic acid.

Some food ingredients exhibit a range of umami characteristics. Soy sauce is often used to increase umami content in foods, since it contains more than 300 flavor compounds, including glutamic acid. It also enhances the sweetness in bitter foods and can be used to balance acidic taste and offer color to the final product. Yeast extracts can contain higher glutamic acid content, higher nucleotide content, or a combination of both, depending on the desired effect.

• Monosodium glutamate (MSG) is the most commonly used taste enhancer. It contains high levels of glutamic acid, enabling manufacturers to easily enhance taste in a wide range of savory foods. MSG—or E621, as it appears on European food labels—is derived mainly from the fermentation of molasses. It is very widely used throughout the food industry, and chances are that unless a food product is labeled as organic it may contain some MSG.

MSG is commonly thought to provide complete umami taste. However, in many cases, nucleotides are also added to foods to work synergistically with the glutamic acid, which alone does not provide the umami taste sought after by manufacturers. Food additives such as disodium inosinate (E631) and disodium guanylate (E627) are high in nucleotides, which can dramatically amplify the umami intensity of glutamate.

Controversy has surrounded MSG because of its links with the so-called Chinese Restaurant Syndrome or MSG sensitivity. Although this syndrome, which is claimed to cause headaches, tingling, and weakness, has not been proven despite numerous scientific studies, there have been enough concerns to make consumers extremely wary of any products containing it. Despite being declared safe by the European Commission’s Scientific Committee for Food in 1991 (SCF, 1991), concern remains high. Co-op recently announced that it was removing MSG from all its own-brand food products.

• Hydrolyzed vegetable protein (HVP) is protein that has been chemically broken down into its component amino acids. These amino acids help to enhance flavor in food and are another way for food manufacturers to enhance taste profiles in reduced-salt foods. HVP is able to provide specific and intense tastes, but some problems still remain when looking to improve taste profiles.

HVP is also currently battling negative publicity following the discovery that the potentially carcinogenic chemical 3-monochlorophane-1,2-diol (3MCPD) could be formed during the acid hydrolysis process used to break down the protein (Anonymous, 2005). Although HVP manufacturers are developing means of eliminating chemicals from the process so HVP can be declared a natural product, most global HVP production is based on acid hydrolysis of soy and wheat proteins and the products therefore cannot be labeled as allergen-free.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

• Yeast extracts are another approach to sodium reduction. Food labeling has become a significant issue for food manufacturers in recent years. Additives and “E-numbers” are treated with caution, despite the E number meaning that an additive has passed safety tests and been approved for use in the EU. Consumers are increasingly choosing products that are labeled as additive-free or allergen-free. This has led to the launch in Europe of 564 new products labeled as being without preservatives or additives or “all-natural” in the first half of 2005 alone (Mintel, 2005). Food manufacturers are seeking natural alternatives to chemical-based taste enhancers, and therefore all-natural taste enhancers such as yeast extracts are benefiting from the waning fortunes of MSG and HVPs.

Although a number of taste-enhancing technologies are used in Europe, yeast extracts seem to offer the greatest benefit in the search for low-sodium/low-salt products. Traditional yeast extracts have been produced on an industrial scale since the 1950s. Previously famous for their clean, bouillon-like taste, they have now become much more sophisticated, and the latest examples offer a more neutral taste profile.

The global market for yeast extracts is currently estimated to be worth $1.5 billion U.S.A handful of European suppliers, including DSM Food Specialties, are at the forefront of yeast extract technology and supply two-thirds of the world’s consumption. The market continues to grow strongly, reflecting increasing demand for natural, effective taste enhancers.

Yeast extracts are widely used throughout the culinary industry and play a crucial role in taste contribution, improvement, and enhancement. The flavor profile of a food product can be improved by the influence of yeast extracts on perceived flavors, acidity, mouthfeel, or saltiness. For example, the tartness of a high-acid, shelf-stable product can be tempered, creating an improved flavor impact. In many applications, a yeast extract can enhance the impact of existing ingredients, such as spices or meat, which can be an opportunity to reduce ingredient costs or maximize the flavor impact.

Advancements in biotechnology have expanded their use considerably. The latest generation of specialty yeast extracts are rich in glutamic acid and nucleotides to deliver powerful taste-enhancement properties. Combined with elevated levels of naturally occurring amino acids and peptides, they enable a significant reduction of sodium content in foods without losing the flavor or salt perception.

Studies by DSM Food Specialties, Delft, Netherlands, show that with the addition of yeast extracts it is possible to reduce salt by 40–60% without compromising palatability, mouthfeel, organoleptic structure, or authenticity of taste. Furthermore, yeast extracts allow manufacturers to make a “clean” label declaration, an important consideration, as consumers are increasingly wary of artificial or chemical additives.

A Soaring Market

The market for low-sodium foods is still growing, in contrast to low-fat and low-sugar “better-foryou” products. With European consumers, pressure groups, and governments all putting increasing pressure on food manufacturers to reduce sodium content in foods, this market is expected to soar. Taste enhancers with multiple functionality, such as yeast extracts, have a crucial role to play for food manufacturers seeking to provide healthy products that both taste good and contain less salt.

by Iwan Brandsma

is Product Manager, Food, DSM Food Specialties,

Savoury Ingredients, Delft, the Netherlands

([email protected]).

References

Anonymous. 2005. Brussels calls for maximum level comments on chemical contaminant in soy sauce. Food Navigator.com/Europe, Oct. 21. www.foodnavigator.com/news/ng.asp?id=63384.

CASH. 2006. Strategy for reducing salt intake. Consensus Action on Salt & Health, UK. www.hyp.ac.uk/cash/information/strategy.htm.

EFSA. 2005a. EFSA provides advice on adverse effects of sodium. Press release, June 22. European Food Safety Authority. www.efsa.eu.int/press_room/press_release/986_en.html.

EFSA. 2005b. Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies on a request from the Commission related to the tolerable upper intake level of sodium. European Food Safety Authority. www.efsa.eu.int/science/nda/nda_opinions/974/nda_opinion_ej209_sodium_summary_en1.pdf.

Fletcher, A. 2005. Selako salt replacer targets health-conscious consumers. Food Navigator.com/Europe, Nov. 15. www.foodnavigator.com/news/ng.asp?d=63893.

FSA. 2004. Nutrition statement. Common statement of representatives of national food safety agencies and institutions involved in nutrition in the European countries and Norway on 13 January 2004. Standards Agency, UK, Feb. 10. www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/webpage/europenutritionstatement.

FSA. 2005a. Research shows consumers choosing less salt. Press release, Feb. 2. Food Standards Agency, UK. www.food.gov.uk/news/pressreleases/2005/feb/saltresearchpr.

FSA. 2005b. Campaign tracking research Aug 2004 – Jan 2005. Food Standards Agency, UK. www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/pdfs/saltresearchgraph01.pdf.

FSA. 2006. Campaign support. Food Standards Agency, UK. www.salt.gov.uk/campaign_support.shtml.

Gibb, S. 2004. Rating retailers for health. Natl. Consumer Council, UK.

He, F.J. and MacGregor, G.A. 2004. How far should salt be reduced? Hypertension 42: 1093-1099.

Intersalt. 1988. Intersalt: An international study of electrolyte excretion and blood pressure. Intersalt Cooperative Research Group. Brit. Med. J. 279: 319–328.

Mintel. 2005. Global New Products Database. Mintel Intl. Group Ltd., Chicago, Ill. www.mintel.com.

SCF. 1991. Reports of the Scientific Committee for Food, 1991, Twenty-Fifth Series, pp.16.

WHO. 2002. World Health Report 2002 – Preventing risks, promoting healthy life. www.who.int/whr/2002/en/.

WHO/FAO. 2005. Joint WHO/FAO expert consultation on diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases, Geneva Switzerland, Jan. 28-Feb. 1. World Health Org./Food and Agriculture Organization, Geneva.