Rethinking Dietary Saturated Fat

Contrary to popular opinion, the link between dietary fat and human disease is not conclusive, which could mean new opportunities for food formulators, especially in the area of low-carbohydrate products

The purpose of this article is to follow up on a discussion initiated in a scientific program session during the 2008 IFT Annual Meeting & Food Expo® and to provide some possible industry ramifications of the current nutritional debate involving the science surrounding low-carbohydrate diets. The session included presentations by David Klurfeld, Human Nutrition National Program Leader, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, on the topic, “Explaining the Public Policy Issues Debate on Dietary Fats,” and author Gary Taubes on “Paadigms of Fat: What is Lost (and What Is Gained) by Consuming a Low-Fat Diet,” as well as my own presentation, “A New Paradigm for Saturated Fats.”

During the session, Klurfeld reviewed many of the observational studies and randomized trials that often are called upon to support the low-fat diet. He emphasized that not all scientific experts agree in the interpretation of these studies purportedly linking dietary fat to human disease. It is interesting to me to read that many scientists are convinced that dietary fat causes heart disease. For example, William Connor writes that “…the low-carbohydrate, high-fat ketogenic diet advocated by Dr. Atkins calls for the consumption of meat, cheese, butter, cream, and eggs in unlimited quantities plus a small amount of carbohydrate. These foods are certainly atherogenic” (Connor, 2005).

In an historical series of articles, Daniel Steinberg writes as if the link between dietary saturated fat, serum cholesterol, and heart disease was closed long ago. “The argument is made that by 1970, the evidence was already strong enough to justify intervention to lower blood cholesterol levels if all the available lines of evidence had been taken into account,” he states. “Yet, it would be almost two decades before lowering blood cholesterol levels became a national public health goal. Some of the reasons the ‘cholesterol controversy’ continued in the face of powerful evidence supporting intervention are discussed” (Steinberg, 2005).

Steinberg further states that: “Dietary intervention to lower blood cholesterol by decreasing saturated fat intake in favor of polyunsaturated fat intake reduces blood cholesterol levels and decreases risk of CHD and other atherosclerotic complications” (Steinberg, 2005).

However, after this evidence was collected and interpreted, the development of “evidence-based medicine” raised the standard of evidence for medical policymakers to hold out until there is a large “outcome study” showing that a particular intervention has reduced morbidity or mortality. This standard was made because many policy decisions based upon observational evidence were not supported by subsequent randomized trials. Moreover, even if there is an effectiveness to an intervention, the magnitude of effect, the cost-effectiveness, and number-needed-to-treat are important to consider before implementation as a clinical policy (Sackett et al., 2000).

Given this new evidence-based medicine standard, several groups have reviewed the randomized, controlled trials regarding dietary fat and cardiovascular disease and found that the evidence was not conclusive (Hooper et al., 2001; Mozaffarian, 2005; Yancy et al., 2003). Consider the following statement from the Hooper article in the British Medical Journal: “Despite decades of effort and many thousands of people randomized, there is still only limited and inconclusive evidence of the effects of modification of total, saturated, monounsaturated, or polyunsaturated fats on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.”

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Carbohydrate, Disease Link Growing

In his IFT presentation, Taubes reviewed the history of the treatment of obesity and found that the consensus view prior to the 1970s was that sugar and starch were the dietary causes of human obesity. He then reviewed how a national low-fat nutrition policy was created but never proven to improve human health over the subsequent decades of testing (Taubes, 2007).

One of the contributing factors to the current debate is that the determination of cardiometabolic risk is changing (Superko, 2008). There is growing evidence that not all low-density lipoprotein (LDL) is bad. It may be that cardiometabolic risk is related to the size of the LDL particle or the number of LDL particles rather than total LDL. Many researchers now think that high levels of small LDLs or merely high numbers of LDL particles confer the cardiometabolic risk. If this is the case, then measurement of LDL without regard to the size or particle number may be non-informative. If LDL size becomes more important than total LDL, then serum triglyceride and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) will rise in importance as therapeutic targets because high triglyceride and low HDL levels correlate well with elevated small LDL levels (Cromwell, 2004). As lowering triglyceride and raising HDL levels becomes more important, then restricting dietary carbohydrate will be of more value because dietary carbohydrate has been known to raise serum insulin and serum triglycerides for quite some time (Reaven, 1986).

Low-carb, High-fat Diets Appear Healthy

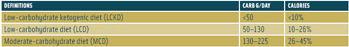

My IFT talk last year focused upon what our research and clinical experience has found: That low-carbohydrate diets improve health parameters despite the high fat (and high saturated fat) content. I suggested that the health effects of dietary saturated fat may be different in the context of a very low–carbohydrate, ketogenic diet (<20 g/day). One way to categorize low-carbohydrate diets is suggested in Table 1. A low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet contains fewer than 50 g/day; a low-carbohydrate diet contains 50–130 g/day; and a moderate-carbohydrate diet contains 130–225 g/day. The sidebar on page 30 shows a handout that outlines the permitted foods on a low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet. The carbohydrates in a low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet will come from non-starchy vegetables. Low-carbohydrate diets may include complex carbohydrates, but do not include sugar, refined carbohydrates, and starchy vegetables. If you think of a low-carbohydrate diet as just eating “real food”—food that is close to its natural form—then this approach will likely lead toward improved health for most people.

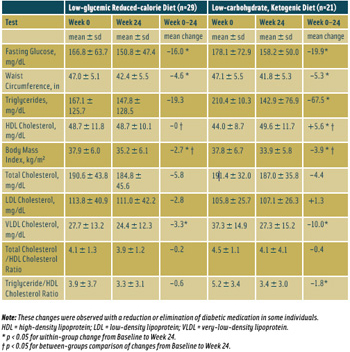

I consider a low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet to be a diet that maximizes the potential to lower blood glucose because the dietary factor that raises postprandial serum glucose and insulin most potently is carbohydrate. This observation led to the use of diets low in carbohydrates for the treatment of diabetes before insulin or other medication therapies were available (Allen et al., 1919). In randomized studies, low-carbohydrate diets have been found effective for the treatment of obesity for durations up to 48 months (Yancy et al., 2004; Shai et al., 2008). Table 2 shows the effect of two types of carbohydrate restriction: low-carbohydrate ketogenic vs low-carbohydrate. The low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet improved all the features of metabolic syndrome.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Principles of Human Metabolism

It is important to remember that protein and fat are needed in the human diet, but it is debatable whether humans need carbohydrate in their diet at all (Westman, 2002). Normal human metabolism has many ways to safeguard an adequate amount of glucose for glucose-requiring cells (Westman et al., 2007). Nearly all cells can use fatty acids and ketones, which provide a substitute for glucose in cells that have mitochondria but cannot use fatty acids (e.g., central nervous system). The hypothesis that dietary fat is harmful needs to be balanced by the knowledge that healthy human tissue consists of saturated and unsaturated fats. Saturated fatty acids constitute half of the acids in membrane phospholipids and a third of the acids in triacylglycerols (Ponds, 1998).

The publication of several large clinical trials that found beneficial effects from low-carbohydrate diets in 2003 created an increase in popularity of the diet (La Berge, 2008). After studying obesity and hyperlipidemia, our research group at Duke has moved on to study these diets in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus and other medical problems (Westman et al., 2008). Other American and international research groups continue to study low-carbohydrate diets and find positive results (Shai et al., 2008). When the Nurse’s Health Study cohort was queried, low–glycemic-load diets were associated with lower cardiac risk than high–glycemic-load diets over a 20-year period (Halton et al., 2006). Another careful short-term evaluation found that substitution of fat for carbohydrate was beneficial for markers of cardiometabolic risk (Krauss et al., 2006).

I don’t think that any new scientific discoveries led to the reduction in popularity of low-carbohydrate diets. It is possible that the new low-carbohydrate products were made too fast without proper attention to palatability, side effects, and cost. I wonder if the death of Dr. Atkins or the bankruptcy of the company with his name mistakenly gave the impression that the diet didn’t work or was unhealthy. (For example, it is not logical to conclude that airplanes can’t fly because an airline company goes bankrupt.)

Fear of Fat

I have suspected that a fear of dietary fat has been one of the reasons for reluctance of general acceptance of low-carbohydrate diets. I suppose that is understandable because if the scientific consensus is divided, what is industry supposed to follow? However, when an unscientific fear of dietary fat pervades the culture so much that researchers who are on study sections that provide funding will not allow research into high-fat diets, and human subjects research committees think that it is “unethical” to study high-fat diets for fear of “harming people,” this situation will not allow science to “self-correct.” A sort of scientific taboo is created because researchers will not submit requests for high-fat–diet grants because of the low likelihood of funding, and the funding agencies are off the hook because they say that researchers are not submitting requests for such grants.

Perhaps a prominent researcher was correct when he recently concluded: “The overall evidence accumulated about diet, disease, and death may be nearing a paradigm shift in which prior observed facts remain while beliefs about their accepted interpretation change” (Lands, 2008). In other words, the consensus opinion is changing.

From my perspective as an obesity researcher studying low-carbohydrate diets, there is definitely a need for products that are low enough in carbohydrate to be of use to individuals who are following low-carbohydrate ketogenic diets (<20 g/day). When our patients notice that they feel better and their medical conditions improve by eating “real food,” they look for foods that are compatible with their new lifestyle. These products should generally contain less than 1 g or 2 g of carbohydrate per serving. We are able to satisfy the “sugar cravings” that sometimes occur during the first few days of a low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet with non-sugar sweeteners. We recommend that people use non-caloric sweeteners if they have the desire to do so. It seems to me that it’s not the sweetness that is causing the metabolic problems; it’s the carbohydrate and calories that are associated with the sweetness. In the development of non-caloric sweeteners, ones that have minimal impact upon blood glucose and other aspects of metabolism like lipolysis, serum lipoproteins, and inflammation would be quite desirable.

To manage weight or prevent weight gain, however, it is important to know if these non-sugar sweeteners provide the same level of reward as sugar when eaten and the same cravings when discontinued because individuals will have the choice between choosing a non-sugar sweetener and sugar for the foreseeable future. It is also important to remember that “sugar-free” does not necessarily mean “low-carbohydrate.” Starchy vegetables, pasta, and rice will be digested and metabolized as their component monosaccharides.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

In summary, it may be observed that there is an ongoing debate regarding the relationship between dietary fat and human disease. A re-evaluation of the diet/heart disease outcome studies has found that the link between dietary fat and heart disease is not conclusive. There has also been a shift in the assessment of cardiometabolic risk from serum LDL to serum triglyceride and HDL. As the focus of cardiometabolic risk changes, it is likely that there will be a change from dietary fat restriction (which lowers LDL) to dietary carbohydrate restriction (which lowers triglyceride and raises HDL). If this is the case, then products to support low-carbohydrate, high-fat lifestyles will rise in importance.

Eric C. Westman, M.D., ([email protected]) is Associate Professor of Medicine and Director of the Lifestyle Medicine Clinic at Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC 27704.

A Low-Carbohydrate Ketogenic Diet Guide

The following is an example of a low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet instructional handout from the Duke Lifestyle Medicine Clinic.

Allowed Foods

This is the first and most restrictive phase of the program. For now, keep the total number of carbohydrate grams to less than 20 g/day. Your diet is to be made up exclusively of foods and beverages from this guide. If the food is packaged, check the labels and make sure that the carbohydrate count is 0 or 1 g/serving.

Eat As Much As You Wish of the Following Foods

• Meat. Beef (hamburger, steak, etc.), pork, ham (unglazed), bacon, lamb, veal, or other meats. With processed meats (sausage, pepperoni, hot dogs, etc.), check the label to make sure that the carbohydrate count is less than 1 g/serving.

• Poultry. Chicken, turkey, duck, or other fowl.

• Fish and Shellfish. Any fish, including tuna, salmon, catfish, bass, trout, shrimp, scallops, crab, and lobster.

• Eggs. Whole eggs are permitted without restrictions; do not use egg substitutes.

Foods That Must Be Eaten Every Day

• Salad Greens. 2 cups a day. Includes arugula, celery, Chinese cabbage, chives, cucumber, endive, lettuce (all varieties), parsley, spinach, radicchio, radishes, scallions, sprouts (bean and alfalfa), and watercress. (If it is a leaf, you can eat it.)

• Vegetables. 1 cup (measured uncooked) a day. Includes artichokes, asparagus, beet greens, bok choy, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower, chard, Chinese cabbage, collard greens, eggplant, green beans, jicama, kale, leeks, mushrooms, turnip and mustard greens, okra, onions, peppers, pumpkin, shallots, snow peas, spinach, string beans, sugar-snap peas, summer squash, tomatoes, rhubarb, wax beans, and zucchini.

• Bouillon. 1–2 cups daily. Clear broth (consommé) is strongly recommended unless you are on a sodium-restricted diet for hypertension or heart failure.

Foods Allowed in Limited Quantities

• Cheese. 4 oz a day. Includes hard, aged cheeses such as Swiss, Cheddar, Brie, Camembert, bleu, mozzarella, Gruyere, cream cheese, and goat cheeses. Avoid processed cheeses, cheese spreads, or cheese foods such as Velveeta.

• Olives (black or green). 6 a day.

• Avocado. 1/2 of a fruit a day.

• Lemon/lime juice. 4 tsp a day.

• Cream. 4 tbsp a day; includes heavy, light, or sour cream.

• Soy sauces. 4 tbsp a day

• Mayonnaise. 4 tbsp a day

• Pickles (dill or sugar-free). 2 a day.

Caution: Use this dietary approach only under the supervision of trained professionals.

References

Allen, F.M., Stillman, E., and Fitz, R. 1919. Total dietary regulation in the treatment of diabetes. Monograph No. 11. Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, New York.

Connor, W.E., Duell, P.B., and Connor, S.L. 2005. Benefits and hazards of dietary carbohydrate. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 7: 428-434.

Cromwell, W.C., and Otvos, J.D. 2004. Low-density lipoprotein particle number and risk for cardiovascular disease. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 6: 381-387.

Halton, T.L., Willett, W.C., Liu, S., Manson, J.E., Albert, C.M., Rexrode, K., Hu, F.B. 2006. Low-carbohydratediet score and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. N. Engl. J. Med. 355: 1991-2002.

Hooper, L., Summerbell, C.D., Higgins, J.P.T., Thompson, R.L., Capps, N.E., Smith, G.D., Riemersma, R.A., and Ebrahim, S. 2001. Dietary fat intake and prevention of cardiovascular disease: Systematic review. BMJ. 322: 757-763.

Krauss, R.M., Blanche, P.J., Rawlings, R.S., Fernstrom, H.S., and Williams, P.T. 2006. Separate effects of reduced carbohydrate intake and weight loss on atherogenic dyslipidemia. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 83: 1025-1031.

La Berge, A.F. 2008. How the ideology of low fat conquered America. J. Hist. Med. Allied. Sci. 63: 139-177.

Lands, B. 2008. A critique of paradoxes in current advice on dietary lipids. Progress. Lipid. Res. 47: 77-106.

Mozaffarian, D. 2005. Effects of dietary fats vs carbohydrates on coronary heart disease: a review of the evidence. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 7: 435-445.

Ponds, C.M. “The Fats of Life.” 1998. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Reaven, G. 1986. Looking at the world through LDL-cholesterol-colored glasses. J. Nutr. 116: 1143-1147.

Sackett, D.L., Straus, S.E., Richardson, W.S., Rosenberg, W., and Haynes, R.B. 2000. “Evidence-based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM.” 2nd ed. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh.

Shai, I., Schwarzfuchs, D., Henkin, Y., Shahar, D.R., Witkow, S., Greenberg, I., Golan, R., Fraser, D., Bolotin, A., Vardi, H., Tangi-Rozental, O., Zuk-Ramot, R., Sarusi, B., Brickner, D., Schwartz, Z., Sheiner, E., Marko, R., Katorza, E., Thiery, J., Fiedler, G.M., Bluher, M., Stumvoll, M., Stampfer, M.J. 2008. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N. Engl. J.Med. 359: 229-241.

Steinberg, D. 2005. An interpretive history of the cholesterol controversy: Part II: The early evidence linking hypercholesterolemia to coronary disease in humans. J. Lipid Res. 46: 179-190.

Superko, H.R., and Gadesam, R.R. 2008. Is it LDL particle size or number that correlates with risk for cardiovascular disease? Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 10: 377-385.

Taubes, G. “Good Calories, Bad Calories. Challenging the Conventional Wisdom on Diet, Weight Control and Disease.” 2007. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Westman, E.C. 2002. Is dietary carbohydrate essential for human nutrition? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 75: 951-952.

Westman, E.C., Feinman, R.D. Mavropoulos, J.C., Vernon, M.C., Volek, J.S., Wortman, J.A., Yancy, W.S., Jr., and Phinney, S.D. 2007. Low-carbohydrate nutrition and metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 86: 276-284.

Westman, E.C., Yancy, W.S., Jr, Mavropoulos, J.C., Marquart, M., and McDuffie, J.R. 2008. The effect of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet vs a lowglycemic index diet on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutr. Metab. 19: 36.

Yancy, W.S., Jr., Westman, E.C., French, P.A., and Califf, R.M. 2003. Diets and clinical coronary events: The truth is out there. Circulation. 107: 10-16.

Yancy, W.S., Jr., Olsen, M.K., Guyton, J.R., Bakst, R.P., and Westman, E.C. 2004. A randomized, controlled trial of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet vs a lowfat diet for obesity and hyperlipidemia. Ann. Intern. Med. 140: 769-777.