Creating Successful Innovation Partnerships

To co-develop innovation with partners and produce value for consumers and customers, Nestlé Co. utilizes open innovation, new business models, trust and goodwill, and the mindset of ‘sharing is winning.’

One of the dominant ways in which intelligence presses forward is through innovation, recognized as a significant contributor to economic growth (The Economist, 2006). The exact definition of innovation varies from person to person. Generally, innovation is the economic application of ideas, technology, or processes in new ways to gain a competitive advantage.

For the food industry and especially for the consumer goods industry, innovation is a combination of a product’s inherent value to the consumer, combined with elements of services and solutions, well-being, good & healthy-for-me, and convenience. In general, well-executed innovation with value for consumers always comes from challenging conventional wisdom and searching, finding, and implementing new solutions to old or new problems. Hence, creating new business opportunities is a direct outcome. The innovation economy is the new Industrial Revolution.

Over the past decades, market forces have pushed many food companies into a process of continuous cost cutting and rationalization. The only way to escape this “spiral of death” is to innovate. This presents new challenges to food technologists; they have to connect the right functional benefits to the emotional benefits to support brand strengths (Juriaanse, 2006). In today’s competitive environment, innovation is a necessity and is probably the only way to survive. It is the new mantra. Innovate or die (Hargadon and Sutton, 2000) could be the leitmotif for all companies. A recent article in BusinessWeek highlights the role of innovation: “Will 2009 be the year of innovation economics? … Innovation is the best—and maybe the only—way the U.S. can get out of its economic hole. New products, services, and ways of doing business can create enough growth to enable Americans to prosper over the long run” (Mandel, 2008). Going hand-in-hand with this mantra is that all innovation emanates from first-class new product development (NPD). Such new product development is critical for success, and must be the “DNA and genes” of every successful company today.

The failure rate of new products is mindboggling (Watzke and Saguy, 2001). Even at a company like Procter & Gamble that has achieved a lot of recognition for its innovation, “nearly half of P&G new product innovations fail to deliver their business objectives or financial goals” (Lafley and Charan, 2008). One out of every two food and drink products to hit the European grocery shelves are removed within two years, leaving the company to bear the considerable costs involved in new product development (Partos, 2008). However, in spite of the high failure rate, each and every company that deals with innovation in any shape or form should make failure an acceptable outcome as it allows innovation to reach further than what is easily achievable and obvious. If failure is not an acceptable outcome, potential innovators would become risk adverse and important innovations and discoveries would simply not happen anymore.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Open Innovation

Open Innovation (OI) is a term promoted by Henry Chesbrough and defined as “a paradigm that assumes firms can and should use external ideas as well as internal ideas, and internal and external paths to market, as the firms look to advance their technology” (Chesbrough, 2003). OI is founded on the fact that, in a world of widely distributed knowledge, companies cannot afford to rely entirely on their own research, and consequently should rely also on outside sources and buy or license processes or inventions (e.g., patents). Additionally, idle internal inventions should be offered externally through a spectrum of possibilities such as licensing, joint venture, spin-offs, etc. In contrast, closed innovation—which was the norm in most food companies in the past—refers to processes that limit the use of internal knowledge within a company and make little or no use of external knowledge. This openness phobia was frequently justified by a false sense of proprietary and confidentiality.

To address the special needs of OI and to provide a wide range of solutions, numerous companies furnish a plethora of services and solutions. Examples include InnoCentive, Innovation Exchange, Ninesigma, YourEncore, UTEK, and Yet2.com.

A few years ago, Nestlé Co. made an important strategic decision, namely, OI as co-creation of value became the new role model for accelerating and optimizing its strive for innovation. The goal: to become the No. 1 consumer goods company for Nutrition, Health, & Wellness. That meant that Nestlé had to dramatically change its ways of thinking and working in all areas of technological, consumer-centric, and R&D-driven developments. Nestlé’s approach to OI is to combine internal resources with external assets. Worldwide, it employs approximately 5,000 people in 24 R&D centers and over 250 application groups, with a total R&D spending of CHF 1.88 billion (Swiss Francs) in 2007.

Nestlé applies OI by tapping into technologies and expertise of more than a million researchers worldwide, including science universities, venture capital, strategic suppliers, and government laboratories. In general, Nestlé has three types of worldwide collaborations: (1) simple contract work carrying out clinical trials or analytical work, (2) more than 140 collaborations with universities, research institutes, and medical centers, and (3) a select number of special strategic Innovation Partnerships (INP). Nestlé’s main goal is to co-create innovation and value through partnerships.

Other companies also focusing on OI include Kraft Foods (Kuhn, 2008) and General Mills (Erickson, 2008). In spite of widespread adoption of cross-boundary innovation management in the food industry, empirical evidence of food companies engaging in OI strategies remains scarce. Peer-reviewed literature does not provide much empirical support for OI practices in the food industry, although firms in this sector appear to be experimenting in different ways with OI strategies. Detailed analysis of these activities and their rationale and market outcome is, with the exception of a few case studies, virtually absent from both academic and practice-oriented, peer-reviewed literature (Sarkar and Costa, 2008).

The three overall objectives of this paper are to (1) highlight some of the steps and processes that Nestlé is applying in its Innovation Partnerships, (2) highlight the fundamental processes and benefits required for enhanced implementation of INP, and (3) suggest several recommendations concerning the paradigm shift required in strategy and business models, education, and the mindset or culture of Sharing Is Winning.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Innovation Partnerships

Collaboration has been a key piston in the engine that is driving economic growth in the new millennium. Innovation in information technology, institutions, and strategic reorientation of technological change has opened opportunity, and competition has put strong imperatives in play for collaborative innovation (Weaver, 2008). In the context of OI, firms increasingly acquire technologies from external sources. Moreover, many firms have recently started to actively commercialize technologies, for example, by means of out-licensing. While some pioneering firms realize enormous benefits from this, many others experience major difficulties in managing external technology exploitation. To overcome these challenges, firms need to establish appropriate strategic technology-planning processes, including the extension of product-technology to integrated roadmaps for OI processes and external technology exploitation (Lichtenthaler, 2008).

The transition to OI is not an easy task. Nestlé’s history reveals three remarkable facts: (1) the company was established more than 140 years ago, (2) it has been exceptionally successful, and (3) nearly all of its flourishing innovations came from the inside. These facts, however, should also be the most important reasons for the need for change, especially when it comes to the source and origin of innovation. Complacency stifles innovation. Nevertheless, it took some work by dedicated and committed people to change the company's approach to innovation. Nestlé’s new innovation strategy focuses on conducting business with its partners. This is termed Innovation Partnerships, and it drives the journey toward what already is described in detail elsewhere as OI (Chesbrough, 2003) and Open Business (Chesbrough, 2006).

The Innovation Partnership paradigm expands the OI definition, namely, a new way to collaborate in all areas of discovery and development with external partners who can bring competence, commitment, and speed to the relationship. The key to achieve this major goal is to accelerate necessary innovation and take the burden of resources and time pressure off the shoulders of a single partner. Working with suppliers is not a new concept. Companies that have implemented total quality management (TQM) programs have found partnerships with suppliers and other business partners to be valuable sources of ideas for innovation (Riederer et al., 2005).

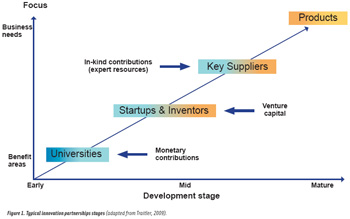

To fully understand where and how INP is created and its possible flow within an organization, let’s look at a simple basic model that distinguishes between the generic stages—early, mid, and mature—of innovation at Nestlé (see Figure 1). In the context of OI, each of these stages requires a different focus:

• Any early-stage idea should fit into at least one of the predefined “benefit areas.” At Nestlé, the benefit areas relate to nutrition (8), compliance and quality (3), and taste (2). These benefit areas are the basic framework for any idea that comes to Nestlé or is developed.

• At a more mature stage, innovation needs a clear business focus and business goals as established by the business at-large and defined in a collaborative fashion between company, technical, and commercial representatives.

The closer Nestlé gets to something its calls “almost ready,” the bigger the need for a business focus in terms of product volumes, production locations, costs, and similar considerations. Irrespective of stage, benefit area, or business focus, the consumer always plays the central role in this innovation landscape.

As a general rule, the solution requester has to let the proposed solution provider know precisely its needs and requirements. The days of companies meeting with their suppliers, where the operative procedure was to “let them parade on the innovation catwalk and show us what they have until we say yes,” are history. Furthermore, it is imperative to share these needs/requirements in an open and clear way with the proposed partner. Hence, a confidential and protective framework must be established prior to such sharing.

Companies engaging in innovation partnerships must ensure that their joint work meets all rules and regulations surrounding antitrust. Everything must be presentable as having a clear innovation goal. It is paramount that everything that is done is transparent and can withstand any scrutiny of any trade commission of any country, especially, of course, in the area of operations.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Sharing Is Winning

Business model innovation is vital to sustaining OI. External technology partnerships allow Open Business Models to accomplish even more (Chesbrough and Schwartz, 2007). Hence, the business climate is focused on collaboration and reciprocation. To survive and to thrive in today’s global world of innovation, companies must seek alliances based on compatible differences. Like innovate or die, partner or perish is the new mantra.

Partnerships are created in order to solve a problem, fill a gap, or find an answer more effectively and more quickly (i.e., time to market). Effectiveness and speed are the operative and overriding principles of any innovation partnership.

At Nestlé, a very simple motto for such a partnership is called Sharing Is Winning. This slogan really describes the spirit of any partnership. It does not suggest a naive approach that either of the partners is giving up any proprietary territory, but rather it expresses the deep respect that partners have for each other as they enter into a co-development.

The journey toward a “perfect” INP passes through three essential stages: (1) establishing trust, (2) good will, and (3) creating value. By teaming up with world-class innovation partners of all sorts, the value creation becomes stronger and, more importantly, happens faster. By finding, adapting, and deploying appropriate outside innovations, Nestlé can substantially extend the scope and accelerate its innovation and renovation pipelines.

Some of Nestlé’s key partners who have been participating in its Sharing Is Winning strategy include Barry Callebaut, BASF, Cargill, Cognis, DSM, DuPont, Firmenich, Fonterra, Givaudan, IFF, Kerry, Mane, Symrise, and Tetra Pak, to name only a few. These Innovation Partnerships have already contributed to more than $200 million in new business with co-developments ranging from new functional soy ingredients, better-tasting soy-based drinks, and new coating systems for ice cream to new nutritional ingredient solutions in pet food and new dairy-based nutritional functionalities. And this is merely the beginning.

In some cases, an organization may experience internal resistance against partnerships. While most stakeholders (e.g., R&D, marketing, sales, management) support partnering objectives, there is always the risk that some may not. Unsupportive stakeholders can kill an alliance before it comes together or slowly eat away at it over time. Hence, management’s role is to prevent these remote situations.

Furthermore, it is increasingly important that organizations implement what in politics would be called “reaching across the aisle” and engage in partnerships between different internal competency groups. Nestlé, for instance, draws upon the expertise of its many geographically and functionally dispersed competencies.

Partnerships minimize risk to an organization. For example, at the onset of any co-development, no investment is needed other than the existing expert resources. It is well understood that existing resources cost money too and that many internal branches of any given organization compete for such resources. However, experience shows it is much easier to ascertain such resources for purposes of new product development and innovative co-developments than it is to secure necessary funds to pay for such NPD or acquire solutions. Moreover, resources can be redeployed to other projects if a co-development should fail. World-class project management in NPD is also paramount. It is vital, upfront, to define and specify crystal-clear goals, resources, timelines, and milestones as well as assigning of intellectual property and value-sharing solutions. Overall, this is a powerful and sustainable model because the risk of too early financial commitments into project(s) is kept extremely low.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Partnerships involve upstream and downstream partners. Upstream partners represent early, mid, and mature stages of innovation. Typically, these partners come from universities, start-up companies, and inventors. They also include large industrial partners (i.e., ingredient and packaging suppliers). Downstream partnerships occur with a select group of large customers (i.e., retailers), with the goal of identifying innovation based on shoppers’ insights and having strong consumer relevance. We have come a long way from the time when manufacturer-retailer relationships were at arms’ length. This two-pronged character of partnerships often leads to NPD that is clearly shopper-insight driven, potentially resulting in services and products that “fly off the shelf.”

Close contact with the consumer is paramount for any R&D organization, so that it can decipher the collected data and transfer it to usable and valuable information (Watzke and Saguy, 2001). The “consumer is the boss” (Lafley and Charan, 2008) and is driving R&D and success in the marketplace (Saguy and Moskowitz, 1999). For instance, in a recent article in The Economist (2008) focusing on innovation in America, the extraordinary willingness of American consumers to try new things was categorized as a vital counterpart of the country’s entrepreneurial business culture.

It is important to note, however, that the INP should consider other customers on its way to creating value. They include the R&D organizations and the business units of the partnerships, to count only a few. This may not be as easy as it sounds as it requires close alignments and careful coordination.

Whether the partnership is upstream or downstream, the underlying principles are the same: Bring together needs and requirements from one group with the competencies and solutions from the other.

Trust, Goodwill, and Value

Partnerships evolve through three essential stages: (1) trust, (2) goodwill, and (3) value (see Figure 2). It is the value creation at the end that is the ultimate goal of any partnership. Without such value creation, the whole concept remains hollow and provides no real merit to both innovation partners.

To drive value creation, organizations should apply a disciplined approach to the innovation process. It is worth reemphasizing that no matter what the nature of the innovation process, well-understood project management tasks and excellent management are vital to continuing success. Without such project management, which includes clear briefs and good understanding of the goals and expectations, many projects are doomed to fail—whether these are run internally or in a partnership model.

Trust, sharing, and agreements are an essential part of INP. An important element in any type of collaboration is first understanding and then further defining the needs of the partners involved. The partner who initiates the relationship because of a need must know which specific competencies and innovative solutions are being offered, and how these competencies and solutions will actually help the innovation. For instance, Nestlé—for its upstream partnerships only—has compiled its future needs and requirements for all its businesses and individual business units and shares this information with its innovation partners.

Before an organization can share this vital and confidential information, legal issues need to be considered. Establishing the legal framework in which to conduct the relationship is paramount. For instance, Nestlé initially used existing agreements (e.g., confidentiality agreements) that spell out under which terms strategic and confidential information could be shared. However, as progress on the path of shared innovation was made, it was found that some secrecy or nondisclosure agreements were inadequate, mainly due to their narrow coverage of mostly only one specific topic (e.g., sharing information in a document). Once proceeding to the second stage—the goodwill phase, it is necessary that partners have the ability to discuss freely and put ideas openly on the table. However, sharing becomes very tricky and far more complicated. New ideas are not necessarily covered by such an agreement anymore, unless one specifies the topic in new agreements each time.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

In order to avoid such obstacles, Nestlé has established master joint development agreements (MJDAs). In principle, a typical MJDA comprises two parts: (1) terms of confidentiality between the two parties as well as possible affiliates of each partner (it may also contain a definition of the potential ownership of the jointly created innovation solutions), and (2) a detailed description of a project resulting from one or more joint ideation meetings or discussions between the partners. Typically, the main body of a MJDA details the project, expectations, resources, timelines, intellectual property, and all other elements necessary for best practices.

MJDA is a crucial element to break the ice and speed up the process. Once MJDAs have been established, it allows partners to enter smoothly into the next phase, defined as “discover the opportunities.”

Intellectual Property

Like most other large industries, the food sector has a strong focus on intellectual property (IP) as an important financial asset. Thus, it is not surprising that food companies try to protect, potentially patent, and trademark as large areas as possible in order to increase their inherent value. Patents are probably the most prominent vehicle in constructing so-called IP fortresses. However, as important as the IP fortress may appear on the surface, it could also be counterproductive when forging strong alliances with potential innovation partners. This is one of the reasons why even large corporations, with partners who typically work in the area of more mature stages of innovations, increasingly turn to early stage co-creation and build the IP fortress jointly and in a more natural and harmonious way.

Organizations can implement several best practices when it comes to sharing intellectual property of jointly created or co-created value. Good upfront negotiations are crucial, not only involving IP experts but also commercial representatives. Such negotiations should be fact-based, non-emotional, and done expediently and with goodwill. Nothing can be more counterproductive to the success of a joint project than overly lengthy and bitter discussions that wrangle over IP and who owns what and why. Often, rights to IP are mistakenly linked only to the specific question of who owns the patent(s). However, patent ownership is too limiting. There are many more elements in the field of IP such as trademarks, manufacturing secrets, know-how, exclusive access to necessary supply chains, and potentially many more.

As a simple rule of thumb, the most straightforward way to share IP is this: Every physical solution, such as ingredients or even technologies, is owned by the competency-providing partner. In turn, the smart applications of this solution are owned by the receiving party, which in our case is the Nestlé Co. The approach that Nestlé developed is based on the principle that the competency-bringer owns the solution(s) and the need requester owns the smart application(s) in specified areas. In this way, the partnership can avoid many unnecessary, unproductive discussions and often unpleasant, relationship-damaging conflicts. Obviously, it’s not always as easy as this and there may arise many complex situations in which, for tactical or strategic reasons, this simple sharing of IP does not apply anymore. For instance, a solution and enabling technology or ingredient that is core to the requester therefore should remain with the requester.

In principle, successful INP should lead to co-created values. The financial investment that happens at the beginning of a simple sourcing approach (i.e., solutions for money) are delayed in the partnership until such time that a value proposition has been established by successfully accomplishing a joint project. Until then, the real investment is the use of expert resources from both partners in the project. Once the co-created innovation can be implemented, solutions have to be found concerning how it would be best to share the commercial values of the innovation. The solution can involve the traditional “goods & services vs cash” model with the partner’s co-creation costs built into the delivery of the innovation. Sometimes the solution can involve other ways to share commercial value, such as open-book and royalty payments.

Commercial considerations must be part of the co-creation process and these commercial considerations should take place at the very onset of any joint project. From a practical point of view, commercial representatives from both partners (e.g., procurement and sales) must be members of the project team, although they should play more of an observational and advisory role.

From Open Innovation to Open Business

The co-creation value process requires that the partners have a framework and an environment conducive to ideation and its execution—the real innovation. Creating value within a well-structured and focused organization is quite difficult. Given the cultural and commercial differences that characterize partners, such creation becomes more complicated and complex when innovation has to be co-created and executed in a partnership mode. To alleviate any possible resistance, it is necessary to highlight a few proven and successful pathways focusing on how innovation should start from a structured and disciplined approach, how to involve many players, and finally how to develop the ideal platform for joint ideation as a first, yet crucial step, in the innovation process.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

New ways of value sharing do not necessarily do away with traditional approaches, but rather better reflect our striving toward the next important stage in the journey of the innovation path. Chesbrough (2006) stated that “companies that keep their intellectual property too close to the vest risk missing out on critical business innovations that idea-sharing could generate. OBMs [Open Business Models] foster collaboration with customers and suppliers to everyone’s benefit.” If we want OI to be sustainable, then OBM is potentially the next step. We need to add new ways of sharing commercial value to the predominant “goods and services vs cash” model.

Organizations that are utilizing INP, and those that will join the train that has already left the station, will have to learn to respect an innovation partner in a different fashion. For instance, the time when suppliers were kept at bay due to competitive and pricing reasons is long gone. The new paradigm calls for sharing the outcome of an innovation partnership, thus reaching beyond the archaic definition of a supplier or contractor. This approach is setting a specific tone for a very different relationship with an innovation partner (that could in some cases even be a competitor). It is clear that OBM should be developed to facilitate value sharing.

Creative Problem-Solving

Innovation can have many faces and can come from many sources. There are, however, several ground principles. The multiplicity of principles is a common pattern when the origin and the generation of innovation are defined. The source of any innovation really lies at the fracture lines of multiple disciplines. It’s always about bringing unity to diversity and bringing people of many different backgrounds and disciplines together. Maintaining an innovation process flow, however, requires a paradigm shift to overcome actual and imaginary hurdles and barriers (Watzke and Saguy, 2001).

The environment in which this multiplicity best thrives should balance the degrees of freedom with disciplined and focused spirit.

If you look at sports where most—if not all—records were achieved during fierce competition, it is not surprising that an overabundance of resources is counterproductive to real innovation. In such situations, solutions are typically enabled too easily. The reality is that often nothing really new and extraordinary can come from such an environment. Lastly, it can be said that true innovation is actually generated in a spirit of deep understanding of people’s needs, dreams, desires, and hopes.

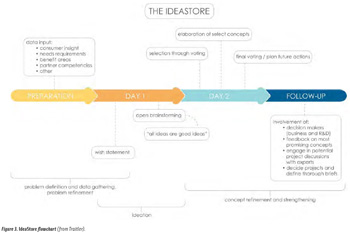

A plethora of creative methods exist for problem-solving (Watzke and Saguy, 2001). To jumpstart INP, organizations need to introduce new, yet proven ways of joint creative-problem-solving tools. The principles of these tools have been described extensively (VanGundy, 1998, 1992). One creative-problem-solving tool is IdeaStore™ (developed by the primary author). IdeaStore (see Figure 3) is a variant of brainstorming. It is based on three main characteristics: (1) facilitation by “visualizers,” (2) large diversity of participants, and (3) disciplined and stringent selection and prioritization process.

IdeaStore uses well-known brainstorming techniques, combined with clear goal setting, diversity, divergent and convergent idea flows, stringent and fact-based selection, as well as the thorough elaboration of concepts followed by prioritizing of the selected ideas. Its main thrust is to discover or to create opportunities by matching needs and requirements with relevant competencies. An IdeaStore session typically takes place over 2 days. The session brings together an approximate equal number of representatives of both partners. For practical reasons, the workshop is led by two facilitators who have a design background as they also act as “vizualizers.” They can capture and visualize images that help better explain the potential concept and give a possible project a face.

The total number of participants should typically not exceed 14. This number enables every participant to creatively contribute to the brainstorming, selection, elaboration, and prioritization process—crucial elements of the IdeaStore exercise. The background of the participants in the IdeaStore session should be as diverse as possible. Based on experience and the business focus of Nestlé, a nutrition-savvy person is always included. Furthermore, Nestlé always involves a person from procurement, so that from the beginning, commercial thinking can flow into the ideation process. Finally, people who can make decisions when it comes time to dispatch necessary resources into projects are also involved.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Every IdeaStore process begins with the definition of the wish statement. The wish statement typically might read: “It would be great if we could ….” The statement will comprise short-term vs long-term concepts. When formulating the statement, organizations must consider such factors as value of concept, whether the concept covers a sufficient business opportunity, availability of resources, realistic timelines, consumer benefits, etc. The statement might also deal with “soft” targets such as building a team spirit between the two partners.

In order to improve the chances of successful follow-up of any of the concepts developed during the IdeaStore exercise, it is advisable to limit the number of projects in the selection process to not more than 10. Once such potential concepts have been elaborated and brought into the format of a concept sheet, they are submitted to the relevant businesses and R&D groups for validation. The typical success rate of this validation is around 30% (i.e., approximately 3 projects are being further elaborated and worked on jointly between the two companies). The pattern that emerges from such workshops can be described typically as 200 10 3, or from 200 ideas to 10 concepts to 3 selected projects. IdeaStore workshops also create an intangible product—team building and an open invitation to continue this spirit of innovative partnership beyond the session. Once the groups interact, they know each other better, they understand what each group brings to the relationship, and the interaction opens new pathways to direct co-creation. Quite often, IdeaStore leads to other innovation activities that involve the partnership. The new innovation activities often transcend the original limited goals and outcomes of the IdeaStore project.

SRI International, Menlo Park, Calif., uses a similar approach to IdeaStore but goes even further. After a first round of 200 10 3, SRI organizes a second workshop on the 3 selected projects and then drills them down to one, which ultimately can be further elaborated and drilled down in a third workshop (Carlson and Wilmot, 2005).

Nestlé uses other similar creative-problem-solving tools. For instance, a tool for packaging innovation is called FastPack™. It has the same roots and elements as IdeaStore. The key difference is that FastPack is designed exclusively to generate a limited number of packaging concepts. The timeline for FastPack is accelerated—concepts can move toward rapid prototyping and consumer research and potential feedback within only a few weeks (Lane, 2002). Like IdeaStore, efficiency, focus, and speed are of the essence. FastPack is a well-proven tool. Many successful Nestlé packaging innovations have come out of FastPack, such as the Mövenpick iconic ice cream tub, new Nescafé containers, coffee creamer containers, new baby food containers, but also shelf-ready packaging solutions, so-called pdq’s (“pretty darn quick”) for large retailers such as Wal-Mart.

Open Social Networks

In today’s business environment, “open social networks” are emerging as increasingly important venues for commerce and, of course, innovation. Google, Facebook, Second Life, and My Space are just a few examples of social networks. They have one major element in common: they all play a role in the “virtual world” on the Internet and Web-based platforms. It is quite likely that these networks will also play a significant role in the food industry (i.e., fast moving consumer goods, FMCG).

What do open social networks mean for a FMCG company? A recent article in McKinsey Quarterly (Bughin et al., 2008) describes the opportunity of such open social networks in more detail. The article points out that the OI paradigm is really the open social component. It is also evident that it will still take awhile until we get there. Yet the way forward appears to be clear. OI is just the first step in this journey. Currently, the answer to this question is highly speculative. FMCG companies, especially those executives entrenched in today’s best practices, will probably be asked to change some of their mindsets, even about methods and ways of thinking that have been successful to date. Organizations will have to transform their rather slow, measured, studied, and occasionally ponderous approach to innovation and execution into a very fast, not always perfect, method but with major opportunities as well. The real protection of innovation will come from speed rather than from patents.

Open social networks will enable organizations to search, find, and implement just about any potential solution to an opportunity from just about any source, and become the best and fastest in translating, adapting, and executing such solutions. It means that we may have to define the field of innovation in a new way. Packaged goods companies may become packaged goods and services companies, making consumers’ lives more pleasant and convenient and bringing affordable and nutritionally sound goods and services to consumers and customers. This might be the real outcome of open social networks in the FMCG industry. Needless to say, this paradigm shift in innovation will have a pronounced impact on future new product development practices. Hopefully, this will also bring a much better understanding of the marketplace and consumers, so that the success rate of NPD will be improved dramatically.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Optimizing the INP Business Model

To meet future requirements and economic challenges, the business model needs to focus on a few important ingredients and formulate around them. Some of these elements are:

• Leadership. Successful INP requires both leadership vision and culture change to embrace all the facets of innovation. Setting quantifiable and crystal clear goals that galvanize action and developing tools that ease the burden on people attempting to promote innovation and change are some of the essential building blocks.

• Strategy. Planning should adapt the increasing importance of external technology exploitation and partnerships. It should also include a clear roadmap where INP could and should be utilized in order to obtain and sustain a competitive advantage.

• Partnerships. The changes in the marketplace no longer sustain extended time for random collisions and interactions to happen to offer solutions and business opportunities. We must create partnerships so that cross-fertilization and synergism will happen.

• Champions. It is well known that almost all market successes are due to the people that drove them, and probably more so for a successful INP. True project champions were, are, and will be essential. It is the responsibility of each company to find its “yellow brick roads” and support and nourish them, sometimes keeping them below the radar, while on other occasions fully exposing and crediting them for their unique contributions and achievements. The structure of the company and its strategy need to be flexible and open to welcome both structured INP and innovative entrepreneurships simultaneously. The implementation is not as straightforward as it sounds, and each company needs to find its own best practices.

• Internal experts. Experts who can speak at “eye level” with external counterparts are essential. Internal experts should also naturally and routinely develop their network and seek external potential solution providers. These unique qualities of the internal experts have played a key role in getting recognition for Nestlé as one of the most innovative companies in the world. It also ensures that potential solution providers will always turn to the Nestlé Co. first with innovative ideas that might fit into the benefit areas or strategic business focus. The experts’ knowledge and capabilities are cardinal elements, and Nestlé places the utmost importance and commitment to its people and their continuous training and development.

• Consumers. Last but probably the most crucial, the business model has to be consumer-centered. This point needs to be interwoven in the fabric of the business model and re-enforced repeatedly.

Education

To prepare for the changes required to embrace, nourish, and sustain OI and INP, the “old” education system of food science and technology will have to undergo a paradigm shift. This will require that food science education move toward an open system, embrace diversity, become multidisciplinary, revise current curricula and incorporate new skills from numerous domains, diversify partnerships, and implement innovative new methods of teaching and interacting with students. Some of these changes have already been implemented in many universities in Europe. For instance, the Erasmus program (named after Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam, whose travels for work and study took in the era’s great centers of learning, including Paris and Cambridge) is the European Commission’s flagship educational program for higher education students, teachers, and institutions. It places great importance on mobility and furthering career prospects through learning. Erasmus forms part of the EU Lifelong Learning Program (2007–2013). It encourages student and staff mobility for work and study, and promotes trans-national cooperation projects among universities across Europe.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

The Mindset of ‘Sharing Is Winning’

The luxury of blocking Open Innovation by the well-known issue of “not invented here” is long gone. There is no OI and no OBM without clearly changing the mindset from “attempting to do everything within” to “sear-ching out the most appropriate partners for success.”

This mindset change can most easily be described as Sharing Is Winning. This descriptive motto does not mean that we naively give away secrets. Rather, we build the framework through appropriate agreements, we share needs and requirements, and we search for the appropriate partner with the appropriate competencies. Jointly, we discover the opportunities, we enter into the trust-to-goodwill-to-co-create value cycle and we stubbornly pursue opportunities professionally, supported through world-class expert resources and first-class project management.

In the end, everything that we do should make sense in terms of value creation. If we do not create value, then we will have failed. Yet, by doing things right, and doing the right things, it’s likely that so much transformation value will be created that there won’t be the nagging question and issues about “what is the right way,” “us vs them,” and “we can’t let go.” Rather, Sharing Is Winning will become the overarching principle. This new mindset will also affect all aspects of NPD. Undoubtedly, new practices will emerge to meet consumers’ expectations and wishes. The end result will be positive—significantly enhanced success rates in the ever-increasingly competitive marketplace that confronts all of us.

Helmut Traitler, Ph.D., is Vice President –Innovation Partnerships, Nestlé Co., 800 N. Brand Blvd., Glendale, CA 91203 and Ave. Nestlé 55 CH-1800, Vevey, Switzerland ([email protected]). I. Sam Saguy, D.Sc., an IFT Fellow, is Visiting Professor (Robert H. Smith Faculty of Agriculture, Food and Environment, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel) and Innovation Partnerships, Nestec Ltd., 201 Housatonic Ave., New Milford, CT 06776 ([email protected]).

This article was adapted from a chapter on Innovation Partnerships as a Vehicle Towards Open Innovation and Open Business. In: An Integrated Approach to New Food Product Development (Moskowitz, H.R., Saguy, I.S., and Straus, T. Eds.) Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, FL. (In press. Expected April 2009).

References

Bughin, J., Chui, M., and Johnson, B. 2008. The next step in open innovation. McKinsey Quarterly. June.

Carlson, C.R. and Wilmot, W.W. 2005. Innovation, the 5 Disciplines for Creating What Customers Want. Crown Business. New York, NY.

Chesbrough, H. 2003. Open innovation, the New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology. Harvard Business School Press. Boston, MA.

Chesbrough, H. 2006. Open Business Models, How to Thrive in the New Innovation Landscape. Harvard Business School Press. Boston, MA.

Chesbrough, H. and Schwartz, K. 2007. Innovating business models with co-development partnerships. Res.-Technol. Mgmt. 50: 55-59.

Erickson, P. 2008. Partnering for innovation. Food Technol. 62(1): 32-37.

Hargadon, A. and Sutton, R.I. 2000. Building an innovation factory. Harvard Bus. Rev. May-June 78(3): 157-166.

Juriaanse, A.C. 2006. Challenges ahead for food science. International Journal of Dairy Technology. 59: 55-57.

Kuhn, M.E. 2008. Driving growth through open innovation. Food Technol. 62(6): 76-82.

Lafley, A.G. and Charan, R. 2008. The Game Changer. Crown Business. New York, NY.

Lane, G. 2002. The Nestlé Co. Private communication.

Lichtenthaler, U. 2008. Integrated roadmaps for open innovation. Res.-Technol. Mgmt. 51: 45-49.

Mandel, M. 2008. Can America Invent Its Way Back? BusinessWeek. Sept. 11.

Partos, L. 2008. Innovation in food products essential to weather economic storm. www.foodnavigator.com. Oct 21.

Riederer, J.P., Baier, M., and Graefe, G. 2005. Innovation Management – An Overview of Some Best Practices. C-LAB Report 4(3): 1-58.

Saguy, I. S. and Moskowitz, H.R. 1999. Integrating the consumer into new product development. Food Technol. 53(8): 68-73.

Sarkar, S. and Costa, A.I.A. 2008. Dynamics of open innovation in the food industry. Trends in Food Sci. & Tech. 19: 574-580.

The Economist. 2006. The Economist Innovation Awards. www.economist.com. Nov. 16.

The Economist. 2008. Innovation in America – A Gathering Storm. Nov. 20.

Traitler, H. 2009. Innovation partnerships as a vehicle towards open innovation and open business. In: An Integrated Approach to New Food Product Development (Moskowitz, H.R., Saguy, I.S., and Straus, T.) Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, FL. (In press. Expected April, 2009).

VanGundy, A.B. 1988. Techniques of structured problem solving. Wiley, John & Sons, Inc. New York, NY.

VanGundy, A.B. 1992. Idea power: Techniques and resources to unleash the creativity in your organization. AMACOM.

Watzke, H.J. and Saguy, I.S. 2001. Innovating R&D Innovation. Food Technol. 55(5): 174-188.

Weaver, R.D. 2008. Collaborative pull innovation: Origins and adoption in the new economy. Agribusiness 24: 388-402.