Cleaning Up Processed Foods

Shoppers are paying more attention to what they put into their bodies, and that is driving the development and reformulation of products with cleaner labels.

Although the concept of “clean label” increasingly appears to be a priority for food and beverage formulators, this unregulated descriptor remains largely undefined by industry and consumers. In fact, definitions vary by the party involved, with ingredient suppliers, food and beverage manufacturers, retailers, and consumers all having their own opinions of what qualifies as a clean label. But because in the end the only thing that matters is if consumers repeatedly purchase the product, their interpretation is what counts.

A Formulating Strategy

Consumers will not find an aisle in the supermarket dedicated to clean-label foods, nor will they see the words “clean label” on a product. This is because clean label is a formulating strategy that involves the ingredients that compose the product and the marketing jargon used to describe them.

Companies must list all the ingredients on the ingredient statement by their common or usual names. And they must abide by all applicable standards and regulations. Products may also include statements such as “all natural,” “organic,” “no antibiotics,” “no GMO ingredients,” “free range,” and “locally grown” (Roller, 2010). All of these items influence a person’s opinion as to whether the product has a clean label or not.

Formulating clean-label foods most often refers to eliminating chemical-sounding ingredients or any ingredient recognized as being artificial, for example, certain colors and flavors. Most ingredients with a name that implies extra processing, such as modified corn starch, are considered unclean. The concept of wholesome complements this definition of clean label.

Another interpretation of clean label is “simple.” This interpretation focuses on ingredient statements that are short with understandable ingredients. One of the first products to take this clean-label approach was Häagen-Dazs Five. This pint ice cream line focuses on the simplicity and goodness of five ingredients—milk, cream, sugar, eggs, and one flavoring ingredient.

Yet another interpretation of clean label emphasizes transparency, or informing shoppers about what’s inside the product in order for them to make informed purchase decisions. For example, shoppers who want a lower-calorie yogurt might be fine with the fact that it contains artificial sweeteners, so upfront disclosure is welcomed and even appreciated. For example, Dannon Light & Fit states on the front panel that the yogurt contains aspartame and acesulfame potassium.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Whether they choose to make good choices or not, consumers want transparency in nutrition information on food packaging, grocery store shelves, menus, and the Internet. This information can be found in fact-based data (e.g., grams of protein, calories per serving, etc.), ingredient statements, front-of-pack labeling, or symbols such as the American Heart Association’s Heart-Check mark. Clean labeling typically involves the ingredient statement, but it may also denote a company’s sustainability efforts—how the food was sourced, produced, and processed, and how it gets to stores and homes (Borra, 2010). The challenge is understanding which of these are important enough for consumers to seek them out.

Focus on Processing

Research shows that consumers would prefer to avoid artificial or overly processed foods. So when clean label is a formulating goal, the emphasis tends to be on the wholesome, natural approach. In fact, according to HealthFocus International, 77% of shoppers are interested in natural foods. But what does natural really mean to shoppers and how important is it? The answers to these questions are largely product specific but also largely dependent on what the product contains (HealthFocus, 2011).

In general, most consumers are suspect of highly processed foods and tend to scrutinize their labels. But even characterizing what is highly processed varies by individual, creating challenges with clean-label formulating.

At the end of 2010, using its ongoing analysis of key trends and developments around the world, Innova Market Insights predicted that “processed is out for 2011” (Innova Market Insights, 2010). And that’s exactly what most product rollouts attempted to embody over the course of the past 12 months.

This is because consumers on a global basis have grown tired of being increasingly disassociated from the foods and beverages they ingest as a result of the products being processed. This is not to say that all processing is perceived negatively. After all, pasteurization is a process that renders fluid milk safe. Because it is unrealistic for everyone’s milk to come fresh from the cow, the process of pasteurization is a necessity. Of course, there are the raw milk extremists who disagree with the benefits of pasteurization.

Nevertheless processed foods are best defined as foods that have been altered from their “direct from Mother Nature” state of being. At IFT’s Wellness 11 conference this past March, HealthFocus International and Innova Market Insights presented a session titled “Processed Foods Through the Eyes of Shoppers.” Included in the presentation was a moderated panel of real shoppers, who shared their perspectives on the topic. When the five primary household shoppers (moms) from the Chicago area were asked their opinion of processed foods, replies ranged from “we try to avoid high fructose corn syrup in our house” and “the whiter the bread, the sooner you’re dead” to “they taste good and kids will eat them” and “they last a long time.”

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Prior to participating in the panel discussion, each mom agreed to review the contents of her home pantry and cupboards and identify purchased items perceived as being the most and least processed. Their revelations confirmed that consumer opinion of processed foods varies greatly. For example, one mom categorized Newman’s Own pasta sauce as one of the most processed foods on hand in her home, while Nabisco Triscuit crackers were one of the least processed. Clearly, here the mom considered manufacturing when determining degree of processing as the sauce states on the label that it is all natural and the ingredient statement is very simple so one would think it is not very processed. But the cracker’s ingredient statement is even simpler: only three ingredients. Plus the cracker package sports a heart health claim. To this mom, a cleaner label implied less processing.

For another mom, Pepperidge Farm Goldfish crackers were a “most processed” item, while Lay’s Classic potato chips were a “less processed” food. The cracker package states that the product is natural and contains no artificial preservatives, but the ingredient statement is rather lengthy. Like the other mom, she interpreted the chips’ simple ingredient statement (potatoes, vegetable oil, and salt) as an indicator of degree of processing.

All five moms claimed that they read labels, particularly on cereal boxes and snacks. They also agreed with the reporting in the HealthFocus Processed Food Study that processed foods are a “negative necessity” in today’s on-the-go society. But when price and convenience are not a factor, those products with cleaner labels are more likely to be purchased for their families, the panelists said.

Surveying Shoppers

To gain additional consumer insight, HealthFocus International conducted a 5,000 shopper syndicated study that explored how shoppers define processed foods; the factors they consider when determining whether a food or beverage is processed or unprocessed; and which brands do the best job of communicating clean label, healthy, and less processed.

Survey findings suggest that the perception of processed has more impact on a shopper’s opinion than does the actual processing that the product undergoes. For example, foods that go through processing by food industry standards, such as pasteurization or canning, are not necessarily considered processed by many shoppers. Only 16% of shoppers surveyed identified canned Progresso tomatoes as processed. Even fewer said Silk soy milk was processed (15%), which is surprising when you consider that this is a fluid product extracted from soybeans (HealthFocus, 2010).

When shoppers were presented with real products to evaluate, their assessment revealed diverse opinions on different products in the same categories. This is where the concept of clean label comes into play because their opinions were often influenced by perception of healthfulness, product purity, and clarity of package information. For example, in general, surveyed consumers thought that low-calorie frozen meals were less processed than standard frozen meals. Whole-grain bread trumped white bread, while organic yogurt was considered less processed than regular yogurt. All of these similar products are most likely manufactured in the same way, yet, because of labeling, they are viewed as being less processed (HealthFocus, 2010).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Also according to the study, similar to the mom panelists, shoppers understand that there is a need for processed foods, as they offer convenience, sometimes safety, and are often very cost-effective snacking and meal solutions. Further, when shoppers read an ingredient label, which most shoppers do to some extent, they try to avoid products with additives, preservatives, and artificial ingredients (HealthFocus, 2010).

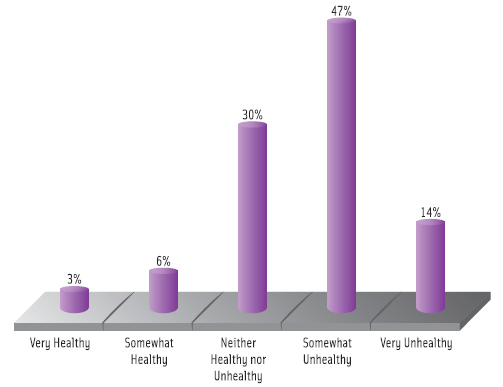

There’s also a correlation between shoppers’ opinions about processed food and their health, with many believing that more processed foods are less healthy. When they were presented with real food examples, most shoppers identified quick-meal mixes such as Hamburger Helper and pre-packaged meats such as bacon and sausage as being highly processed (HealthFocus, 2010).

Shoppers understood that breaded chicken products such as nuggets—staples in most households with young children—are highly processed meat products (HealthFocus, 2010). Most likely, though, if presented with a cleaner-label version, this would improve product opinion, possibly reducing the perceived degree of processing even though the products may be manufactured in the exact same way.

The study also suggests that younger women are more likely to think that highly processed foods are unhealthy. This is important for food manufacturers to consider when they develop new products (HealthFocus, 2010). Clean-label formulating strategies can provide assistance (Williams, 2011).

Cleaning Up

Examples from the Innova Market Insights database show how food companies use clean-label attributes to minimize the negative perceptions of highly processed foods. In 2010, Heinz tomato ketchup was reformulated to remove high fructose corn syrup from the ingredient list and was rebranded Simply Heinz. The Pillsbury refrigerated dough line now includes Pillsbury Simply Buttermilk Biscuit, with front labels indicating that “simply” refers to the naturalness of the product, emphasizing that the product now contains “no artificial colors, flavorings, or preservatives” (Williams, 2011).

In the United Kingdom, food activist Jamie Oliver has taken his tag line of “keep is simple” to retail, creating an extensive range of products made with ingredients he proudly calls attention to as being wholesome and recognizable.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

In addition to simple, terms such as “natural,” “pure,” and “real” are increasingly appearing on product labels. For example, in South Africa, retailer Woolworths now offers a private label line of ice cream products sub-branded as Real Dairy. In Canada, Nestlé also offers a Real Dairy ice cream line. Packaging for the cappuccino variety reads: “Cappuccino-flavored ice cream made with fresh cream, sugar, eggs, and real coffee. No artificial colors. Made with simple ingredients like fresh cream, sugar, and eggs. It’s real, done right.”

In the United States, Nestlé’s Coffee-mate brand, which has long been associated with nondairy (i.e., artificial) coffee creamer in powder and liquid form, can now be found on refrigerated dairy creamers branded Natural Bliss. The product is described as being made with only four simple ingredients: milk, cream, sugar, and natural flavor. Natural Bliss rolled out shortly after Borden Dairy introduced La Crème coffee creamers, which the company said were the first 100% real dairy, lactose-free, naturally flavored creamers in the U.S.

The importance of pure claims is exemplified by Albert Heijn organic yogurt in the Netherlands. In 2008, the company made a very small “honest and pure” claim on yogurt tubs; by 2010, that claim evolved into the sub-brand of Pure and Honest. Labels explain that the product range is produced or purchased with extra care for humans, animals, nature, or the environment.

“Minimally processed” claims are often used by chef-inspired retail products, as the claim suggests that the product is close to homemade. For example, new frozen Frontera Gourmet Mexican Pizzas, developed by globally recognized chef Rick Bayless, state on front-of-package labels that the product is all natural, contains no artificial ingredients or preservatives, and is minimally processed. This language suggests to the consumer that the red, yellow, and poblano peppers on the Roasted Vegetable variety were prepared by Bayless or one of his sous chefs.

Another way to make consumers aware of the simplicity and wholesomeness of a product is to instruct them to read the ingredient statement. That’s what is going on in Canada with McCain’s Garlic Fingers bread snacks, which carry a front-of-pack flag reminding consumers that the product contains “no unpronounceable ingredients.”

Also in Canada, Pure Kraft salad dressing lists some—but not all—of the ingredients on the front display panel to give the impression of a more natural product. Shoppers who read the ingredient list will be quick to find canola oil listed as the first component of the product; however, the company neglects to identify it on the front and instead first lists extra virgin olive oil, an ingredient that clearly resonates with consumers as being a pure, wholesome, good-for-you oil. Not to say canola oil is not the same, but remember, labels are all about consumers.

Clean-labeling strategies continue to evolve. Food manufacturers must decide if clean labeling is a function of research and development or marketing, or both. Remember that shoppers are saying they want less, in terms of unnecessary or possibly even unhealthy ingredients. What they want is more of foods that Mother Nature would have been proud to serve her family.

Barbara Katz, a Member of IFT, is President, HealthFocus International, Suite 220, 100 2nd Ave. N, St. Petersburg, Fla., 33701 ([email protected]). Lu Ann Williams, a Member of IFT, is Head of Research, Innova Market Insights, Marketing 22, 6921 RE Duiven, the Netherlands ([email protected]).

References

Borra, S. 2010. Clean food labeling & sustainability benefit claims: What do consumers want? What are the legal requirements? What if compliance is not enough? Presentation at Annual Meeting, Institute of Food Technologists, Chicago, Ill., July 17-20.

HealthFocus. 2010. Processed Food study. HealthFocus International, St. Petersburg, Fla. www.healthfocus.com.

HealthFocus. 2011. Natural Food and Beverage study. HealthFocus International, St. Petersburg, Fla. www.healthfocus.com.

Innova Market Insights. 2010. Trends for 2011. www.innovadatabase.com.

Roller, S. 2010. Clean food labeling & sustainability benefit claims: What do consumers want? What are the legal requirements? What if compliance is not enough? Presentation at Annual Meeting, Institute of Food Technologists, Chicago, Ill., July 17-20.

Williams, L. 2011. How to create un-processed appeal. Presentation at Wellness 11, Institute of Food Technologists, Chicago, Ill., March 23-24.