In Food We Trust: Issues of Food Integrity

The level of trust consumers have in the U.S. food supply is diminishing: What can stakeholders do to stop this descent?

The food industry has a history of meeting the ever-changing demands of consumers, government, and public health stakeholders. For example, after the passing of the U.S. Enrichment Act of 1942, food manufacturers began supplementing refined grains with iron, niacin, riboflavin, and thiamin to help prevent consumer deficiencies in these micronutrients. In 1996, folate was added to the list to address neural tube defects in unborn infants. Nevertheless, the food industry is now sometimes portrayed as responsible for obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and other ailments that plague society (Prentice and Jebb, 2003; Ludwig and Nestle, 2008; Brownell, 2012). Considerable skepticism around industry-funded research, with intense scrutiny of funding sources and outcomes, contributes to a pervasive aura of distrust surrounding the food industry. As a result, the industry must react to any warranted or unwarranted health or nutrition issue that materializes. This combination effectively erodes consumer confidence in the U.S. food supply.

Perception vs Reality

During the fat-phobic years of the 1990s, the industry developed low-fat products and added compounds considered beneficial—calcium, vitamin D, fiber, protein, vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants—to turn products into functional foods. The early 2000s brought the era of trans-fat elimination, driven by specific cities across the United States and mandatory labeling requirements on the Nutrition Facts Panel. A significant reduction in the use of high fructose corn syrup as a sweetener was largely the result of consumer sentiment and perception of its harmful effects rather than validated scientific research. The low carb movement of the past few years has precipitated hundreds of products whose carbohydrate calories have been reduced to help manage weight and diabetes and prevent other ailments purportedly exacerbated by carbohydrates.

More recently, because the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans advise consumers to reduce their daily sodium intake to less than 2,300 mg, the food industry has been reformulating products with lower sodium levels, facing the concomitant challenges of taste, food safety, and stability. Public health professionals and consumers are pressuring the industry to make these changes despite the absence of a mandate requiring food manufacturers to reduce sodium content.

Moreover, now that a sizeable number of Americans are seeking gluten-free products, the industry is faced with yet another challenge: researching, developing, and marketing products that are gluten-free. This determined goal of reformulation is feverishly underway despite the fact that only 1% of the population is estimated to have celiac disease—the only medical condition known to actually require such a diet. And finally, government and consumer demand for sustainability has the industry looking for more environment-friendly ways to produce, process, package, transport, and sell products.

Consumer Trust in the Food Industry

In its annual online study of more than 30,000 consumers in 25 different countries, the 2012 Edelman Trust Barometer© indicates that distrust is increasing among most sectors of society, including business, banking, and energy. However, among the general population trust in the food and beverage industries actually ranks second highest of any sector, behind technology (Edelman, 2012b). In fact, trust measured in 2012 has grown slightly since 2010 among informed publics. However, 72% of those surveyed are swing respondents, who neither trust nor distrust the food and beverage industries. These data signify an opportunity to win over a large segment.

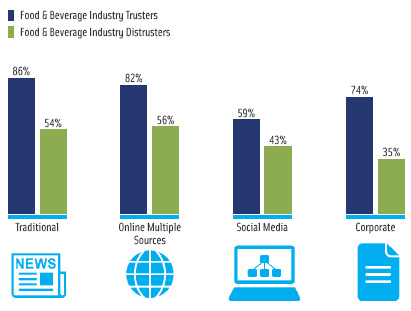

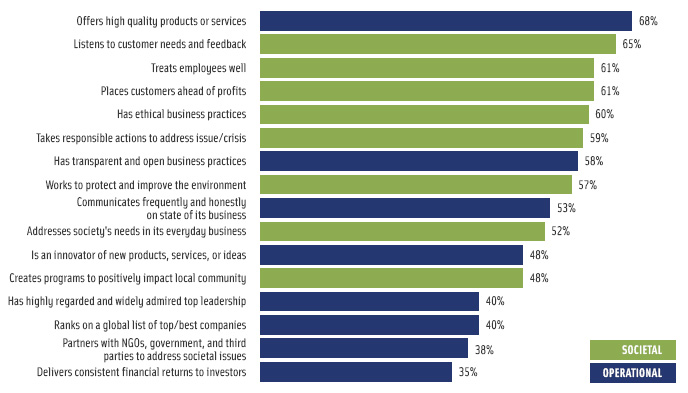

Interestingly, preferred sources of information for company announcements varied between those who trust and those who distrust the food industry, with trusters relying first on traditional sources (newspapers, television, radio, and magazines) and distrusters turning first to online search engines for their information (see Figure 1). While industry trusters and distrusters both rank academics and technical experts within a company as credible spokespeople, distrusters rank a “person like yourself” as the most credible spokesperson, indicating that anecdotes and personal experiences shared by friends and family are more likely to influence their decisions. Among trust-building attributes, high quality products and services rank the highest, followed by listening to customer needs and feedback, treating employees well, putting customers first, and having ethical business practices (see Figure 2). Any industry that wants to improve its success in today’s market should make efforts to meet these attributes.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Even though trust in the food industry ranks high against other global business segments, vulnerabilities still exist. Edelman’s most recent Field to Fork survey reveals that 55% of Americans believe the U.S. food production system is on the wrong track (Edelman, 2012a). The study also reveals three key areas where consumer expectations of the food industry could impact trust: product portfolio, transparency, and shared value. Consumers expect more healthy foods that taste good and fit within their budget, and product changes that improve upon their healthfulness. Seventy-five percent of those surveyed say they want nutrition information that is easy to use; 69% say it is important to know where the food comes from; 65% say it is important to know how their food was processed. In addition, there is a strong desire for industry engagement in societal issues, with 86% saying businesses should place equal weight on societal interests, 82% saying business should aim to improve the health of the public, and 67% believing it is important to solve community nutrition problems.

Because the food industry enjoys a higher degree of trust than many other segments of society, there is reason for optimism. However, this level of trust must be preserved above all else. In addition, the swing category represents an area where positive changes can be made to grow the segment of consumers who trust the industry. While continuing to deliver on operational attributes such as quality products and innovation will remain important, moving beyond operating to leading through authentic, ethical, and transparent communications and engagement in matters of importance to society will additionally make inroads to optimizing the trust of the masses.

Confidence Generates Trust

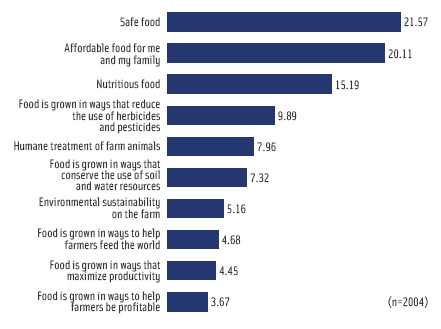

In 2011, the Center for Food Integrity (CFI) conducted research to gauge the level of concern consumers have about key life and current-event issues and to examine consumer support for farming. Results from more than 2,000 internet respondents showed that consumer concerns are many. About two-thirds of surveyed consumers reported that they are concerned about the U.S. economy; unemployment; rising food, energy, and healthcare costs; and personal finances. More than half consider the safety of imported foods a top concern. And about four out of 10 consumers rated humane treatment of animals, environmental sustainability in farming practices, and global warming as their biggest agricultural concerns and primary influences for food choices (see Figure 3).

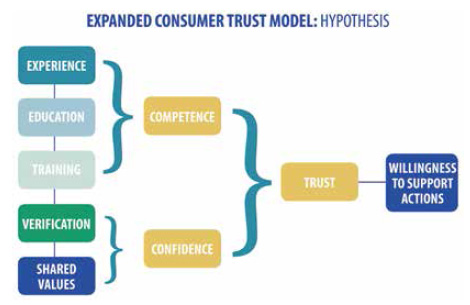

The CFI’s consumer trust model shows that confidence is a much stronger predictor of trust than competence. In fact, perception of shared values, an indication of confidence, is three to five times more important in building trust than demonstrating competence. Competence is strongly related to experience, training, and consumers’ level of education (Sapp et al., 2009). Therefore, to gain more trust from consumers, the food industry needs to focus its efforts on gaining consumer confidence by finding areas of common ground and through more traditional means such as explaining the knowledge and experience necessary to conduct business. For example, in marketing and consumer educational materials, it would behoove the industry to communicate its commitment to some of the same causes and issues held by consumers, such as improving the carbon footprint and sustainability of products, enhancing the health-promoting effects of individual foods, and demonstrating commitment to the overall health and well-being of the population. Understanding reality-based issues such as economic constraints, weight management, and the importance of convenience in food preparation are also critical to reaching consumers and building trust.

Building trust takes time and will be enhanced by transparency. Those in the food industry need to engage consistently in practices that are aligned with the values and expectations of stakeholders. No single effort or initiative will reverse the mistrust of the food industry; however, the industry can progress in the right direction by creating a foundation of shared values and supporting it with credible information from trusted sources. Increased trust levels will contribute to a higher degree of willingness by consumers to support preferred industry practices (see Figure 4).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Beyond Trust: Establishing Integrity and Credibility

Numerous articles have been published on the potential for bias in industry-funded research (Myers et al., 2011; Pyke et al., 2011; Rochon et al., 2011) and the relation between funding source and scientific conclusions (Lesser et al., 2007; Nkansah et al., 2009, Rowe et al., 2009; Myers et al., 2011). Critics plead for nutrition professionals to follow ethical guidelines when conducting industry-funded research yet, at the same time, admit that industry funding is not the only type of funding susceptible to bias or falsification (Cope and Allison, 2010; Nicklas et al., 2011). In the past decade, the conflict-of-interest issue has evolved from initial concern surrounding the pharmaceutical industry and the medical profession to a more general concern about scientific research and all for-profit industries. Such speculation casts doubt over the credibility of science-based nutrition research, implying that the funding organization benefitted in some way from the results and conclusions drawn. Industry-academic partnerships as a result are often formed on shaky ground, with each party moving forward as if in a minefield. Other sources of bias include desire for fame and respect among peers; the imperative in academia to publish; passion; personal ideology, philosophy, and/or political orientation; nationality or ethnicity; and financial gain.

The International Life Sciences Institute, North America, has addressed the myriad of potential biases by developing guiding principles for funding food science and nutrition research (see sidebar on p. 36). The principles should help restore integrity and trust in scientific research funded by for-profit entities. In the meantime, all segments of the food industry must work to recognize and minimize bias, thereby improving the food supply for the health and well-being of Americans.

What Should Food Industry Professionals Do?

In order to establish confidence in the food industry that earns trust from consumers, food industry professionals can work to increase assurance and overcome perceived bias among consumer and health professional stakeholders. The end result will be improved trust, integrity, and confidence in a food supply that is critical to the health and well-being of all Americans. To reach this goal, food industry professionals should do the following:

• Examine every study independently to merit its worth.

• Consider the whole body of research before drawing conclusions from a single study.

• Adhere to ILSI’s Guiding Principles when conducting any kind of research, and insist that others do the same.

• Communicate in an unbiased fashion with clients and consumers.

• Respect and maintain the higher trust the industry enjoys globally.

• Seize the opportunity to convert the swing consumer into a trusting consumer.

• Strengthen the trust attributes that go beyond the license to operate to the license to lead.

• Understand and act on the sources of information and authority that matter most to the audience.

• Encourage young investigators.

• Put a face to the organization.

• Engage and communicate with consumers, using channels appropriate to each segment.

• Find and communicate shared values.

• Remember that transparency is key.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

ILSI’s Eight Guiding Principles

In the conduct of public/private research relationships, all relevant parties shall do the following:

1. Conduct or sponsor research that is factual, transparent, and designed objectively; according to accepted principles of scientific inquiry, the research design will generate an appropriately phrased hypothesis and the research will answer the appropriate questions, rather than favor a particular outcome.

2. Require control of both study design and research itself to remain with scientific investigators.

3. Not offer or accept remuneration geared to the outcome of a research project.

4. Prior to the commencement of studies, ensure that there is a written agreement that the investigative team has the freedom and obligation to attempt to publish the findings within some specified time frame.

5. Require, in publications and conference presentations, full signed disclosure of all financial interests.

6. Not participate in undisclosed paid authorship arrangements in industry-sponsored publications or presentations.

7. Guarantee accessibility to all data and control of statistical analysis by investigators and appropriate auditors/reviewers.

8. Make clear statements of their affiliation; require that such researchers publish only under the auspices of the CRO.

Lori Hoolihan, a Professional Member of IFT, is Manager, Nutrition Research, Dairy Council of California, Irvine, Calif. 92612

([email protected]).

Sylvia Rowe, a Professional Member of IFT, is President, SR Strategy, Washington, D.C. 20036

([email protected]).

Mary K. Young, a Professional Member of IFT, is Executive Vice President, Senior Food & Nutrition Strategist, Edelman Public Relations, Denver, Colo. 80118 ([email protected]).

Stephen Sapp is Professor, Sociology Dept., Iowa State University 50011 ([email protected]).

Guy Johnson, a Professional Member of IFT, is President, Johnson Nutrition Solutions LLC, Minneapolis, Minn. 55416

([email protected]).

References

Brownell, K. 2012. Thinking forward: the quicksand of appeasing the food industry. PLoS Med. 9(7): doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001254.

Cope, M.B. and Allison, D.B. 2010. White hat bias: examples of its presence in obesity research and a call for renewed commitment to faithfulness in research reporting. Int. J. Obes. (Lond) 34(1): 84–83.

Edelman. 2012a. Field to Fork 2012. Available at: http://www.edelmanberland.com/portfolio_item/field-to-fork-2012/.

Edelman. 2012b. 2012 Edelman Trust Barometer. Available at: http://trust.edelman.com/.

Lesser, L.I., Ebbeling, C.B., Goozner, M., Wypij, D., and Ludwig, D.S. 2007. Relationship between funding source and conclusion among nutrition-related scientific articles. 2007. PLoS Med. 4(1): doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040005.

Ludwig D.S. and Nestle, M. 2008. Can the food industry play a constructive role in the obesity epidemic? JAMA 300(15): 1808–1811.

Myers, E.F., Parrott, J.S., Cummins, D.S., and Splett, P. 2011. Funding source and research report quality in nutrition practicerelated research. PLoS One 6(12): doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028437.

Nicklas, T.A., Karmally, W., and O’Neil, C.E. 2011. Nutrition professionals are obligated to follow ethical guidelines when conducting industry-funded research. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 111(12):1931–1932.

Nkansah, N., Nguyen, T., Iraninezhad, H., and Bero, L. 2009. Randomized trials assessing calcium supplementation in healthy children: relationship between industry sponsorship and study outcomes. Public Health Nutr. 12(10): 1931–1937.

Prentice, A.M. and Jebb, S.A. 2003. Fast foods, energy density and obesity: a possible mechanistic link. Obes. Rev. 4(4): 187–194.

Pyke, S., Julious, S.A., Day, S., O’Kelly, et al. 2011. The potential for bias in reporting of industry-sponsored clinical trials. Pharm. Stat. 10(1): 74–79.

Rochon, P.A., Sekeres, M., Hoey, J., Lexchin, J., et al. 2011. Investigator experiences with financial conflicts of interest in clinical trials. Trials 12: 9, doi:10.1186/1745-6215-12-9.

Rowe, S., Alexander, N., Clydesdale, F., Applebaum, R., et al. 2009. Funding food science and nutrition research: financial conflicts and scientific integrity. International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) North America Working Group on Guiding Principles. Nutr. Rev. 67(5): 264–272.

Sapp, S.G., Arnot, C., Fallon, J., Fleck, T., et al. 2009. Consumer trust in the U.S. food system: an examination of the recreancy theorem. Rural Sociology 74: 525–545.