Certifying Organic

FOOD SAFETY & QUALITY

The organic food and beverage market in the United States grew by 9.4% in 2011 to $29.2 billion, representing 4.2% of the total $703 billion U.S. food and beverage market, according to the 2012 Organic Industry Survey conducted by the Organic Trade Association (www.ota.com). And according to the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture (USDA), 28,779 organic farms and processing operations in 133 countries, including about 17,600 in the U.S., are certified as meeting the USDA’s organic regulations.

The USDA’s Organic Regulations

The Organic Foods Production Act of 1990 gave the USDA authority over agricultural products sold, labeled, or represented as organic within the United States. The USDA’s National Organic Program (NOP) (www.ams.usda.gov/nop) set standards for agricultural products represented as organic and began its oversight of organic operations in October 2002. With certain exceptions, each operation that produces or handles crops, livestock, animal products, or other agricultural products represented as organic must be certified by a certifying agent accredited by the USDA. Published in Section 205 of Title 7 of the Code of Federal Regulations, the standards include requirements and prohibited practice as well as the National List of allowed and prohibited materials.

A 15-member National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) appointed by the Secretary of Agriculture has sole authority to recommend adding materials to or removing materials from the national list. The NOSB consists of four farmers/growers, three environmentalists/resource conservationists, three consumer/public interest advocates, two handlers/processors, one retailer, one scientist (toxicologist, ecologist, or biochemist), and one USDA-accredited certifying agent. The board reviews all materials every five years and recommends renewals, removals, and changes. The board met most recently in May 2012.

To meet the USDA’s organic standards, operations must not use prohibited pesticides, synthetic fertilizers, sewage sludge, irradiation, or genetically modified organisms in the production of organic crops. For certified organic animal products, operations must meet animal health and welfare standards, refrain from using antibiotics or growth hormones, use 100% organic feed, and provide animals with access to the outdoors.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Organic Claims

Food products bearing organic claims must comply with both the USDA organic regulations and the labeling regulations of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The FDA does not have a definition for the term “organic” on food labels. The USDA allows three basic types of claims. To be labeled “100% Organic,” a product must be made entirely of organic ingredients. To be labeled “Organic,” a product must contain at least 95% organic ingredients; the remaining 5% must be consistent with the National List and not commercially available as organic. And to be labeled “Made with organic [ingredient]” (specifying ingredients or food groups), a product must contain at least 70% organic ingredients; if the product contains less than 70%, no organic claim is allowed on the principal display panel, but the ingredient list may state which ingredients are organic.

The “USDA Organic” seal may be used on labels of products claiming “100% Organic” and “Organic” but not on labels of products claiming “Made with organic [ingredient].” Labels must also list the name and address of the agent that certified the product as organic and can bear the logo of the agent in addition to the USDA seal. The regulations also apply to alcoholic beverages. For wines to be labeled “100% Organic,” all the ingredients must be organic, no sulfites can be added, and only 100% organic processing aids can be used. To be labeled “Organic,” all varieties of grapes used must be organic and no sulfites can be added. And to be labeled “Made with organic [ingredient],” at least 70% of the ingredients must be organic. The NOP’s Program Handbook provides owners, managers, and certifiers of organic operations with information and instructions that can assist them in complying with the USDA’s organic regulations. The handbook, most recently revised in March 2012, is available via the NOP website at www.ams.usda.gov/nop.

Certification

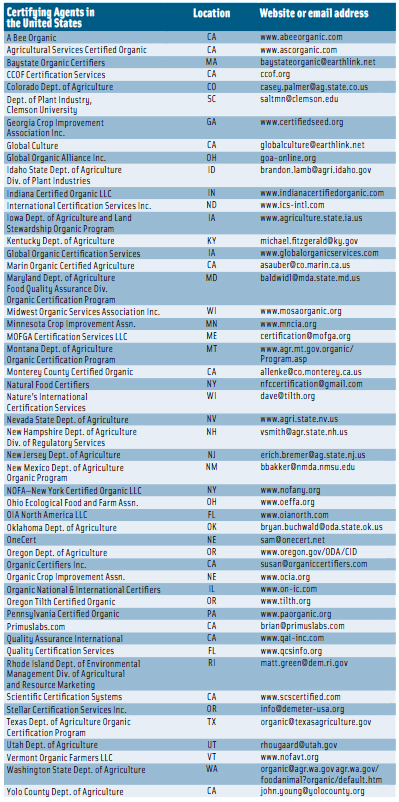

For an operation such as a farm or a processing facility to represent its products as organic, a USDA-accredited certifying agent must certify that the production and handling practices meet the NOP standards. At the end of March 2012, there were 50 accredited certifying agents in the United States (see p. 116) and 41 in other countries (see p. 117). To become certified, farmers and handlers must submit specific information, such as the type of operation, to an accredited certifying agent; the substances applied to the land in the previous three years; the products being grown, raised, or processed; and an organic system plan describing the practices and substances used in production, monitoring practices to be performed to verify that the plan is effectively implemented, a record-keeping system, and practices to prevent commingling of organic and nonorganic products and to prevent contact of products with prohibited substances. Applicants must keep records of the production, harvesting, and handling of its agricultural products for five years after certification.

For an operation such as a farm or a processing facility to represent its products as organic, a USDA-accredited certifying agent must certify that the production and handling practices meet the NOP standards. At the end of March 2012, there were 50 accredited certifying agents in the United States (see p. 116) and 41 in other countries (see p. 117). To become certified, farmers and handlers must submit specific information, such as the type of operation, to an accredited certifying agent; the substances applied to the land in the previous three years; the products being grown, raised, or processed; and an organic system plan describing the practices and substances used in production, monitoring practices to be performed to verify that the plan is effectively implemented, a record-keeping system, and practices to prevent commingling of organic and nonorganic products and to prevent contact of products with prohibited substances. Applicants must keep records of the production, harvesting, and handling of its agricultural products for five years after certification.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

The certifying agent reviews the applications, conducts an onsite inspection, and grants certification if the applicant meets the standards. Each certified operation is inspected at least annually. Operations must notify the agent of any changes that would affect compliance, such as application of a prohibited pesticide to a field. Unannounced inspections can be conducted at any time if there is reason to believe that an agricultural input or product has come into contact with a prohibited substance or been produced using a prohibited method.

Certifying agents take samples for residue testing in an accredited laboratory, using AOAC International’s Official Methods of Analysis or other validated methodology for determining the presence of contaminants in agricultural products. If test results indicate that the product contains pesticide residues or environmental contaminants that exceed the FDA’s or the Environmental Protection Agency’s regulatory tolerances, the certifying agent must notify the pertinent agency.

The USDA has said that analytical methods capable of determining multiple pesticide residues in a single analysis have been developed in recent years. The QuEChERS method has been accepted by pesticide residue analysts, and some modifications have been introduced to ensure efficient extraction of pH-dependent compounds, minimize degradation of susceptible compounds, expand the spectrum of matrices covered, and improve recoveries of pesticides not analyzed in earlier original reports. Because not all registered pesticides can be reliably determined using the QuEChERS method and no method exists that will analyze all registered pesticides efficiently, the NOP created a list of about 190 target analytes. The list includes all pesticides, metabolites, and environmental contaminants that have been detected in samples analyzed for the USDA Pesticide Data Program.

The USDA has said that analytical methods capable of determining multiple pesticide residues in a single analysis have been developed in recent years. The QuEChERS method has been accepted by pesticide residue analysts, and some modifications have been introduced to ensure efficient extraction of pH-dependent compounds, minimize degradation of susceptible compounds, expand the spectrum of matrices covered, and improve recoveries of pesticides not analyzed in earlier original reports. Because not all registered pesticides can be reliably determined using the QuEChERS method and no method exists that will analyze all registered pesticides efficiently, the NOP created a list of about 190 target analytes. The list includes all pesticides, metabolites, and environmental contaminants that have been detected in samples analyzed for the USDA Pesticide Data Program.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

The NOP recommends that laboratories attempt to analyze as many compounds on the list as possible. Samples are primarily tested for organophosphates and organochlorine in the multiple-residue test, but a sample can be tested for a particular pesticide not included in the multiple-residue test when the certifying agent suspects that the pesticide has been used. The laboratories have to be accredited by the International Standards Organization, participate in an international proficiency test program, and be capable of screening for the target pesticides using gas chromatography and/or liquid chromatography coupled to a mass spectrometer (GC/MS or LC/MS) or tandem mass spectrometers (MS/MS).

Miles McEvoy, Director of the NOP, said that certified agents may do analytical testing for any kind of prohibited substance but that most are for pesticides, antibiotics, hormones, and genetically engineered (GE) substances. GE testing is not done very often, he added, because verification of ingredients is done by auditing where the ingredients come from rather than by analytical tests. In April 2011, the USDA proposed that certifying agents conduct residue testing from at least 5% of the operations each year. McEvoy said that the USDA expects to issue a final regulation later this year. To maintain accreditation, each of the certifying agents is audited by the NOP twice or more every five years, with onsite assessments to determine if the agents are implementing the requirements appropriately.

Since organic agriculture is a global system, McEvoy said, the United States signed an equivalency agreement with Canada that went into effect on June 30, 2009, allowing products certified as meeting USDA organic regulations or Canadian organic regulations to be sold as organic in either country without requiring certification in both countries. A similar agreement with the European Union went into effect June 1, 2012. These equivalency agreements, he said, reduce paperwork redundancy, open up markets for U.S. producers and handlers, may lead to increased sales and job growth, and are especially good for small- and medium-sized companies.

McEvoy said that keeping up with the expanding organic industry is a major challenge ahead. There are a lot of opportunities in organic production and handling and some new areas where the USDA is working to get standards established. For example, the USDA is hoping to issue a proposed rule on organic pet food standards later this year and a proposed rule for organic aquaculture products next year. He added that the USDA is also working to improve the information that it provides to trade entities and consumers. The challenge is to update the information technology to provide better service to the organic community and consumers.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Certifier’s View

Jake Lewin, Chief Certification Officer at California Certified Organic Farmers Certification Services LLC (www.ccof.org) —the largest certifying agent in the United States—said that requiring any product labeled organic to be certified by a third-party certifier is the value and strength of the NOP. It assures customers that their products meet the same standards no matter where they make organic purchases.

Lewin said that as the market grows, certifying agents’ systems and approaches will have to evolve to meet the larger market demand for organic products. Certifiers will need to become increasingly sophisticated in their skills, approach to compliance investigation, and knowledge of legal issues. They have to invest in their own skills and infrastructure to be sure they are supporting the growth of the marketplace and are not the limiting factor. They have to provide competent enforcement and application of the rules.

Food Technology Articles on Organic Foods

“Is The Pathway to Health Organic?” by Toni Tarver discusses whether superior health claims for organic foods are substantiated by scientific studies (published March 2012).

“Navigating the Natural Marketplace” by A. Elizabeth Sloan discusses the growth of “natural” vs “organic” foods and beverages (published July 2011).

“The Paradox of Organic Ingredients” by Debra Van Camp et al. discusses the USDA organic regulations and an approach to developing organic ingredients (published November 2010).

“Organic Food Claims in Europe” by Johannes Kahl et al. discusses what is needed to further develop the European organic food market (published March 2010).

“The Changing Face of Organic Consumers” by MaryEllen Molyneaux discusses how the values that drive consumer behavior can help food and beverage companies provide more meaningful organic products (published November 2007).

“Navigating the Processed Meats Labeling Maze” by James N. Bacus discusses how the development of natural, organic, and uncured meats requires a thorough understanding of ingredients and processing techniques (published November 2007).

“Organic Foods” by Carl K. Winter describes IFT’s Scientific Status Summary that comprehensively compares organic and conventional foods (published October 2006).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

“Organic Growing Pains” by Carl. K. Winter discusses the contrasting views of the Organic Trade Association and the Organic Consumers Association (published January 2006).

“Organic Foods Manufacturing and Marketing” by Thomas B. Harding Jr. and Linda R. Davis discusses what manufacturers must do to enter the rapidly growing organic foods market (published January 2005).

“Organic Standards” by R. Elaine Turner discusses the labeling regulations established by the National Organic Program (published June 2002).

“The Natural & Organic Foods Marketplace” by A. Elizabeth Sloan discusses the growth of the natural and organic foods market (published January 2002).

“The National Organic Program: An Opportunity for Industry” by Joe Montecalvo discusses the implementation of the National Organic Program (published June 2001).

Neil H. Mermelstein, a Fellow of IFT, is Editor Emeritus of Food Technology

[email protected]