Chef Gale Gand’s Sweet Success

CULINARY POINT OF VIEW

Gale's Recipe: Butter Ball Cookies

Growing up with artists as parents, it was easy for Gale Gand to find herself studying metalsmithing in college. However, she found her true calling while waitressing at a local restaurant. From there, her entrepreneurial spirit and artistic nature lead her to become a nationally acclaimed pastry chef, restaurateur, cookbook author, television personality, and James Beard Award winner.

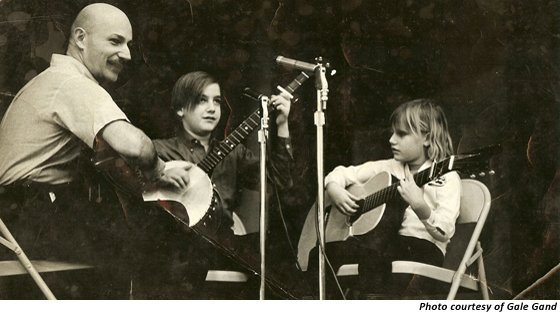

KELLY HENSEL: While pursuing a degree in silver and goldsmithing, your discovered your passion for the food industry through an after school waitressing job. What led you down the path to pastry?GALE GAND: I was in art school getting my Bachelor of Fine Arts with a major in silver and goldsmithing—or metalsmithing as it is sometimes called—and a minor in painting. My dad was a folk singer in the 60s and a jazz trumpet player. And my mother was sculptor. So I always joke that I was raised by wolves—a creative family with very few boundaries and limits. My brother’s a musician as well, and there’s just sort of an entrepreneurial spirit that runs through my family as a way to use our arts to make a living.

So while I was in art school I waitressed because I was literally a starving art student. I had never waitressed and it turns out that I was a great waitress. I loved explaining the food, I loved helping people choose what dishes to order, and I loved calming them down if they had a rough day. I loved all the nurturing aspects and the entertainment aspects of it.

So that was how it started. And then one day we had a line cook not show. It was 4:30 p.m. and he still hadn’t shown up for his shift, and they looked at me and said “Gale, can you cook?” And I said “No, I’m from the North Shore of Chicago, we make reservations.” My manager threw an apron at me and she said “You can cook now. Get in the kitchen.” So it was really a shove that got me in the kitchen. I went crying. I was terrified. I thought this is crazy and for about six seconds I was just petrified, and then I had this strange sense of calm come over me as if I had found my home. As if I was speaking a language that I was fluent in, but I didn’t remember learning.

I’ve talked to other people who are in artistic fields that say the same thing—that it was like a calling practically, and you found yourself within this thing. I remember that night after I worked the line I ran home and called my dad and said “Guess what? I found out what I really want to be, I want to be a chef.” Keep in mind this was the late ’70s, before chefs like Wolfgang Puck legitimized our profession. So my poor father, he dropped the phone, and when he came back on the line he finally said “Well, I guess everybody’s got to eat.” That was his enthusiasm. It seemed like a really unsupportive thing to say. But now 40 years later I realize he was like in a Zen way totally right. Everybody does have this universal survival thing we all need to do every day and look how it connects me with everybody.

So, that’s how I got into the food industry. I did finish my degree, which was a struggle because I really just wanted to be cooking and reading cookbooks and working at the University College until 2:00 in the morning and getting carpal tunnel because I was working so much. But I stayed in there, got my degree.

And pastry was a great fit—it was a perfect fit for me. Pastry’s all chemistry and physics—that’s the underlying bone structure to pastry—but then there’s this creativity on top of that. And if you’re confident and the ingredients excite you, then you can do amazing things.

HENSEL: When you first started out and you discovered pastry was where you wanted to be, who influenced you? Who was your mentor?

GAND: I didn’t have a lot of mentors. I used to read Gaston Lenôtre’s books. He was a pastry chef in France. He wrote some very visual step-by-step books. His photos had every step of the recipes shown so that you could understand the map of where to start and where to finish, and what the steps were along the way. I basically just cooked my way through his books with a French friend of mine, Muriel. She helped me understand what was meant by everything. That was how I learned.

And then I went to La Varenne in Paris for a couple of summers. I also studied with Albert Kumin [former White House pastry chef]. He had a teaching school outside of New York City, and I went and studied with him for a while.

But, because I’m an artist I actually try not be influenced by other people. I don’t want my work to be derivative. I certainly look at what Pierre Hermé does because I think he’s one of the most forward thinkers in pastry right now. I’ll go to his shop in Paris. But I also look back to tradition a lot. I do a lot of sort of retro and throw-back desserts. For example, I really like Fudgsicles, and so I’ll make a dessert that pays homage to the Fudgsicle. Or, remember lipstick candy? I wanted to make that. Sometimes it’s a sensation, like the peeling off of the paper, the gold off the lipstick. So I’ll make a dessert where you have that same physical experience. Lots of stuff is experiential.

Sometimes it’s just inspired from a piece of china. I saw this candleholder in Crate & Barrel and it had six depressions that you put votive candles in. It was like a glass tube and I thought you could put sauces in that. I had just gotten a divorce, and I wanted to do this dessert called the banana split-up, like the banana split. Sometimes I manifest what’s going on in my life in my desserts and I name them such, like the banana split-up. So it was all the components to a banana split—there were maraschino cherries, nuts, caramelized banana slices, and all the garnitures—and then you got ice cream and you built your own. It was sort of a banana split, split apart.

HENSEL: You mentioned that there’s an obvious structure to baking. The chemistry involved in pastry is much more precise than cooking. How do you operate within the physical parameters of baking while pushing the boundaries to create new, unique deserts?

GAND: Well, it can be daunting knowing that there are absolutes within ingredient combinations. It can also be very comforting because that means things are reliable and they come out the same each time. You can count on that. So I think I actually found comfort in pastry because I knew if I cooked sugar to 360 degrees and added this amount of cream and this amount of butter and this amount of salt, I would get the same salted caramel sauce recipe every time. So I like the control that pastry allows me because the ingredients are so consistent. You know butter’s butter, there’s 84% and 82% but I can know that. I can check the label and know that, so that things don’t come out surprising.

GAND: Well, it can be daunting knowing that there are absolutes within ingredient combinations. It can also be very comforting because that means things are reliable and they come out the same each time. You can count on that. So I think I actually found comfort in pastry because I knew if I cooked sugar to 360 degrees and added this amount of cream and this amount of butter and this amount of salt, I would get the same salted caramel sauce recipe every time. So I like the control that pastry allows me because the ingredients are so consistent. You know butter’s butter, there’s 84% and 82% but I can know that. I can check the label and know that, so that things don’t come out surprising.

As I mentioned, my dad’s a musician and he has a music school that he started 50 years ago when I was little, and so I always see things in like musical analogies. There’s a certain amount of the classics like you need to know how to read music and you need to know how to play G chord. But once you know a G chord then you’re allowed to deviate, then you can improvise. And I see baking the same way—you have to know the rules and then you’re allowed to bend them. Once you learn the language you can learn where the bends can happen, where the flexibility is.

I pride myself on sharing that information with people to get them in the kitchen and have more successes. A lot of people have this sort of fear of frying, like a fear of making pie crust or certain things they’re afraid to try in the kitchen because they’ve heard that they’re hard and can be a disaster. What I like to do is decipher a recipe and figure out which steps are not so important. So a recipe may say to add a teaspoon of sugar at a time when you are making a meringue. But it actually doesn’t really matter that much, you can pour it in all at once and you’ll be fine in certain recipes. So I like to take away some of the daunting bits of recipes. And be upfront about the ones—the steps—in a recipe that you can’t skip. Like, you must chill this shortening before you put it in with your flour to make your pie dough.

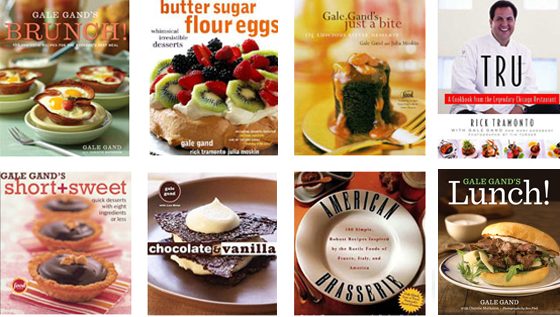

HENSEL: It sounds like teaching has always been kind of a part of what you do. Your cookbooks are not just a collection of recipes—they have a tutorial voice for the reader. Teaching seems to be in your DNA. What draws you to teaching?

GAND: I’m writing one book at a time, so I didn’t necessary see it that way, but I love that you saw it as this body of teaching. I think a lot of cookbooks don’t take a teaching approach because someone said “Hey you know you should have a cookbook to go with the restaurant.” I’m not even sure if they test recipes.

I get a ton of joy from cooking, and so I wanted you to have that too. How can I help you have the experience I have in the kitchen because it is just beyond words just how wonderful it is. Not only the actual of creaming of butter and adding sugar and watching that logical transformation happen. But the smell in your house and the love you get from your kids and the satisfaction you get from feeding people and nurturing them. It’s also the dance of the physical. As I’m adding cream and whisking it in, there’s a physical part to it that feels like a dance to me. And just living in the kitchen in general—moving with confidence. I really get into it, and it keeps me extremely happy so I want people to have that in their lives too. That’s part of the motivation. Part of it feels good to teach somebody something because they usually say thank you, and they’re just so appreciative of it.

You know when I really think about your question—because I don’t seem to ever get asked this—but my dad’s a teacher. I watched my dad be a teacher for 50 years. He’s a musician and he can play any instrument. If someone calls his music school and says do you have bagpipe lesson, my dad would go teach himself the bagpipe to answer that question. So we started a music school in my house when I was like six, because he played guitar at home and the neighbors heard about it, and they would approach him saying that they wanted to learn how to play. And so for the past 50 years of my life people have come up to me and said “Your dad taught me how to play banjo.” Or, “Your Bob Gand’s daughter? He taught me how to play mandolin.” For like 40 years of my life I was Bob Gand’s daughter—that’s who I was. And I sang and played with my dad. We had a family band called The Gand Family Singers. We played at Disneyland; we played for the World’s Fair in Montreal. That’s the only way we took a family vacation was if my dad could book us a job. So I always joked we were like the Von Trap family.

My dad taught me how to perform and how to connect with an audience you’ve never met and will never see again, but still have an intimate experience with them and how to teach. So I think my love of teaching comes from watching my dad teach our whole community music.

HENSEL: And now you’re doing the classes at Elawa Farms. What is that experience like for you?

GAND: So, Elawa Farms is a historic organic farm in Lake Forest, Ill. It’s absolutely beautiful. It was one of the Armour Family [one of Chicago’s oldest and most distinguished families] properties; it was like their weekend farm. It was a very unique design at the time it was built—like 100 years ago. I spent two years being their Chef-in-Residence, so I was cooking from stuff they grew there for their three-day-a-week farmers’ market and then doing all their pies for Thanksgiving and all the gingerbread and stuff for the Christmas market. And then I would teach classes—adult and kid’s classes—once or twice a month at the farm.

You know when I got my show on Food Network [Sweet Dreams] in 2000, I got that call and I did a little bit of “why me?” because I knew everybody wants a show. They said it’s very challenging to find a chef who is comfortable on camera, can teach, and can actually cook, and they were looking for chefs with those three components. They could find someone who was a great cook and could actually teach, but as soon as the camera went on they broke out in a cold sweat. Or someone who’s great on camera, but couldn’t explain what they were doing. So, I obviously have this gift of gab, but I also have the ability to explain what my hands are doing without my hands stopping. Like some people stop and they talk and then they move, and you have to like move and talk at that same time.

HENSEL: I want to talk a little about your experience at Tru. It seemed to be a real pastry-centric environment. How did pastry and savory work together there?

GAND: Most of the restaurants that I have worked at or have been a partner in or helped found are very pastry-centered restaurants, and that’s what happens when you let a pastry chef be a partner. We’re like, “We need a bigger pastry kitchen. We need a bigger pastry program.”

And for many, many years, I cooked with Rick Tramonto, who is my ex-husband now, but we were married for 12 years, and I think we cooked together off and on for like 20 years. A lot of chefs like having a pastry chef because chefs don’t always understand the intricacies of pastry. It’s just like a foreign language to them, and so often they’ll have a pastry chef and defer to that pastry chef, which I think is part of why I liked that area so much because the chef would be like “Whatever you want to do, Gale, is fine, just get it done.” I was my own boss in most respects.

So Rick was really happy to have a pastry chef partner to know that area was taken care of, and not just pastry and desserts, but I did all the breads—anything involving flour. We made the pastas for the hot line. We made the brioche buns that went with the chocolate foie gras dish, which was an appetizer. So it kind of took a whole area off his mind, which was what he needed.

HENSEL: And it sounded like while you were doing pastry at Tru that you tried to tie it in with the savory side. Like, if there was a flight of savory dishes and the customer moved on to dessert, there would be something that tied them together.

GAND: Our prix fixe menus were called collections. It was sort of like here’s the spring collection, like in haute couture, and we would have a group of spring dishes that was a progression, and desserts followed the same. We had a chocolate collection, a fruit collection. We just had a regular dessert collection. So there were these sort of montages or collages or collections of stuff. The philosophy of the food was the same from savory to sweet, which is that we were doing fine dining with a sense of humor. So we wanted Michelin star service, the best of everything in terms of tabletop, whether it was Riedel crystal or the kind of linens we used. But then we always had our little playful twists in the food throughout the entire menu, and it was colorful too. I think my art background and my design background definitely seeped into Rick’s aesthetics, and so the food presentations were a little, kind of boundary-less and a lot more creative and artistic than maybe other chefs who didn’t go to art school and didn’t have a Bachelor of Fine Arts.

HENSEL: Like you just said, they are basically creations of art on a plate that you can eat.

GAND: It really is. I mean, I was an artist who did non-edible work for years, and the problem is if you don’t sell that stuff, you have store it somewhere. I love the volatileness of the medium. When I was trying to explain it to my dad, I’m like “It’s fine art, dad.” It’s more of a fine art than fine art because it involves all five senses. And it’s not stagnant. It’s reactive and alive and I just love it.

One of the things I get to do now is I get to work for food companies doing R&D and recipe development, which is really fun because they’ve got so much capability that restaurants don’t.

HENSEL: You worked with Breyers for a contest they were running a few years back, right?

GAND: Yeah, and I did some sundaes for one of their ice cream shops. Right now I do work for Storck. They make Werther’s Caramels. So I developed a salted caramel brownie recipe for their website that uses their new baking caramels, which just came out this fall. So, I get to help launch products and think up ways to use them. I was just down at the Food and Wine Festival at Disney and did a caramel apple tart with their baking caramels and then did the salted caramel brownies as well. I get to sort of teach people about stuff and turn them on to new things but also be a part of the development of the product or how they promote the product or how it’s packaged. I get to complain about how I hate unwrapping those caramels from that other company. I’ll ask them “Can we do something with that then?” Then they develop a wax paper twist for the caramel—kind of like caramels you’d buy in a general store.

HENSEL: When did you start working more with manufacturers and food companies like Storck?

GAND: It’s kind of been throughout my career to be perfectly honest. Because I am chatty I do a lot of ideation meetings and just idea-generating stuff. So I’ve worked for Kraft and Keebler, and it’s just always kind of been there. I do some work for Challenge Butter right now. We had a contest with them. It was a charity fundraiser where I raised money for my local food pantries.

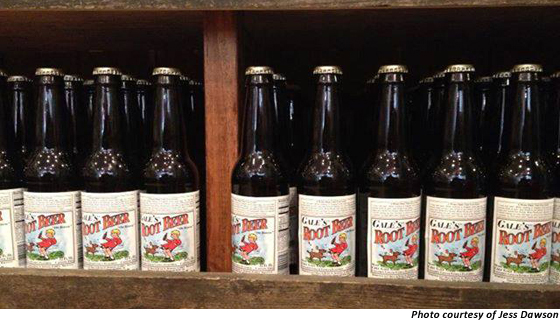

I’m at this great place in my career where I can do corporate or commercial work and then also writing and I have my root beer company [Gale’s Root Beer]. It’s a nice combination. Although I remember the president of Coca-Cola used to come into Tru to eat, and every time he came in, I’d go to their table and I’d say, “When are you going to buy out my root beer company so I can retire from all of this craziness?” Like for all the 16-hour days I’ve put in for 30 years, I kept thinking the irony is that I’ll probably retire on the root beer. I’m still waiting for that call.

So, my root beer is artisanal. It’s made with cane sugar. It’s cinnamon, ginger, and vanilla flavored and Nielsen-Massey makes my vanilla for it. It’s locally bottled here in Chicago, and I’ve been doing it since 1994. And it’s sold nationally. My distributor is European Imports which was bought by Sysco last year.

HENSEL: Well craft root beer seems to be all the rage now. Why did you start your root beer line?

GAND: I lived in England and they don’t have root beer there. The sassafras flavor was used for medicinal purposes during the war, so it tastes like medicine to the British. It’s like if we had Listerine soda pop here—no one would buy it. So they can’t sell it.

I was there for three years. When I got back to the States I swore I would never let that happen to me again. I’m never going to be without root beer again. So that was the motivation—just so I would always have some. But since I wanted the root beer, I decided I would just make like another 499 cases for the rest of the world.

HENSEL: How much are you producing a year?

GAND: It’s like 5,000 cases, and there’s 24 bottles to a case. I probably do a batch a month, and I do 500 cases at a time. So it might be like 5,000 to 6,000 cases a year.

HENSEL: How does the manufacturing process work? You said you produce it locally. Do you work with a company that helps you bottle it and everything?

GAND: Yes, I have a co-packer [Filbert’s Root Beer]. So I start the process of infusing cinnamon stick and ginger root and then take that to my co-packer, and he’s adding the cane sugar, the Nielsen-Massey vanilla, the water, and the CO2. I have the labels shipped to him. He bottles it. They’re third generation root beer makers on the south side of Chicago, and they’ve been my co-packer for as long as I’ve been bottling—around 18 years so.

HENSEL: There are a lot of trends in the pastry space right now. Cupcake trucks, cronuts, bacon on everything. How do you see the role of the pastry chef evolving?

GAND: Well, obviously, I’m glad for trends because it allows journalists to be able to write and focus on desserts and pastry. And it’s just sort of interesting—this idea that great minds think alike and what are great minds thinking about right now. So I like that there are trends. We're not all these individuals … we are kind of like one big beast that moves slowly across the creative field.

The nice thing about the pastry chef is it’s not just after dinner. We take care of breakfast, we take care of parties. We take care of special occasions, such as wedding cakes. I mean, there is so much diversity to what you can do and where you can be involved as a pastry chef.

HENSEL: On a personal note, I know that family is very important to you. Do your daughters and son have an interest in baking or cooking?

GAND: I cook a lot with my kids, Gio especially because he was an only child for eight years, so he got a lot of one-on-one time in the kitchen. He’s an outstanding cook now, a very confident cook. I had to bring him to the restaurant a lot because it would be spring break and there was no school, but I had to work, so he’s now this kid who can break down lobster faster than anybody I know.

It’s not his passion but it’s plan B. Being a chef is sort of if everything else fails. He’s very friendly and social, so he actually had an after school job being a line cook, and they kept putting him out front with the customers because he’s very warm and connecting.

The girls [9-year-old twins, Ella and Ruby] do sometimes join me in the kitchen but not as much as Gio did, and I think it’s because they’re twins. They have each other to hang with and with twins it’s a little trickier cooking with them. You have to make sure they each have their turn at the mixer and you have to have a job for everybody.

I usually do a cooking demonstration in their classes every year. So they are learning some performance skills and public speaking skills. And they come on stage with me a lot at the Chicago Botanic Gardens or other events. I invite them up on stage, partly for their personal development but partly for the audience so they can see, you know, if this six-year-old can make this you should be able to.

I sometimes do after school classes too, like after school enrichment classes, and what it does for me is I know that by the time these kids are in eighth grade or high school, they’ve probably cooked with me four or five times. So, they have four or five dishes they can do. They can make Thai spring rolls so they will not starve in college.

That’s sort of my goal. I’m like, all right, these kids can make a pumpkin muffin and they can do crepes and they’ve got a little repertoire that they’ve picked up in spite of their parents’ fear of cooking.

HENSEL: Last question. You are stuck on a desert island. Name one savory and one sweet dish you couldn’t live without.

GAND: The sweet was harder, but the savory, like I didn’t even have to think about it. It’s fried chicken. I can’t live without fried chicken. And the dessert one, ironically, I have a book Chocolate and Vanilla, so you would think I’d be like a chocoholic. But I’m so not. It’s just some really good bread pudding with raisins in it. Made with half and half and heavy cream, whole eggs, raisins, and vanilla extract and maybe some bourbon. Make it with brioche or some challah. I’d just be so happy.

Gale's Recipe: Butter Ball Cookies

Perfect for holiday cookie exchanges

Makes 40–50 cookies

Ingredients

- 1 cup unsalted butter

- 1/2 cup sugar

- 1 3/4 cups all-purpose flour

- Raspberry jam or ganache (3 ounces semi-sweet chocolate melted with 1/3 cup cream)

- Vanilla sugar for rolling

Directions

- To make a ganache, chop the chocolate and place it in a small bowl. Heat the cream until it comes to a boil then pour it over the chocolate and let sit 30 seconds to melt the chocolate. Whisk it to combine well then let it cool until it’s a spreadable consistency.*

- In a mixer fitted with the whisk attachment, beat the butter on medium speed until it’s light and fluffy, about 3–5 minutes. Mix in the sugar and when the mixture is well blended add the flour and mix until it forms a dough. Wrap the dough in plastic and chill for at least 3 hours to make it easier to handle. This also helps prevent the balls from flattening out too much when they’re baked.**

- Preheat the oven to 375°F.

- Taking off small pieces of dough with your hands, roll small (3/4-inch) balls of dough (about the size of a hazelnut in the shell). Chill them for 30 minutes in the freezer then place them 2 inches apart on cookie sheets to allow for spreading. Bake for 10–12 minutes or just until the cookies are firm but not browned. Remove from the oven and let cool on the pan.

- Spread the flat face of half of the cookies with the jam or ganache and top with a second cookie to form a little sandwiched ball. The filling will not show very much. Once you’ve sandwiched them all together, bury them and roll them in vanilla sugar to coat the entire outside.***

Do-aheads

* The ganache can be made up to a week in advance and kept in the refrigerator. Let it warm up to room temperature to make it spreadable.

** You can make this dough up to a week in advance and keep it chilled or you can form the balls right after you make the dough and keep them chilled or frozen until you’re ready to bake them.

*** The cookies can be kept at room temperature for 1 week or frozen, well-wrapped, for 1 month.