Reining in Adulteration

FOOD SAFETY & QUALITY

Economically motivated adulteration (EMA) of food—a form of food fraud involving intentional adulteration for financial gain, such as by addition of or substitution with a lower-value substance or other means—is estimated to cost the food industry $10–$15 billion per year. It has been around since ancient times and can constitute a food safety problem if the adulterants added to a food or beverage is toxic or otherwise causes harm. In the United States, concern about adulteration of food led to the passage of the Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906 and the eventual establishment of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Economically motivated adulteration (EMA) of food—a form of food fraud involving intentional adulteration for financial gain, such as by addition of or substitution with a lower-value substance or other means—is estimated to cost the food industry $10–$15 billion per year. It has been around since ancient times and can constitute a food safety problem if the adulterants added to a food or beverage is toxic or otherwise causes harm. In the United States, concern about adulteration of food led to the passage of the Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906 and the eventual establishment of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

EMA became widely publicized in 2007–2008 when pet foods and infant formula adulterated with melamine resulted in widespread illness and fatalities. Among recent incidents of EMA was the addition of horse meat to meat products in the United Kingdom in January 2013. Various organizations in the United States have been actively working on the EMA problem.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (www.fda.gov) held a public meeting on May 1, 2009, to discuss ways in which industry and regulatory agencies could better predict and prevent EMA. In September 2011, the agency established a working group on EMA comprising FDA staff from all product centers, the Office of Regulatory Affairs, and the commissioner’s office. According to FDA spokesperson Sebastian Cianci, the primary goals of the working group were to promote cross-agency communication and enhance information sharing and transparency with stakeholders, including industry. Activities of the working group resulted in a central email address ([email protected]) for reporting economic adulteration and a July 2012 FDA notification advising industry to be aware of the potential for substitution or use of oils, glycerin, and proteins derived from the Jatropha plant as they may contain toxic compounds.

While public health and safety are always the FDA’s first priority, Cianci said, the FDA will act whenever it identifies economic adulteration in a regulated food product to get that product off the market. An example is the import alert that the FDA issued on July 24, 2013, telling FDA field personnel that they could detain, without physical examination, pomegranate juice that is adulterated or misbranded due to substitution. The FDA had received complaints alleging that pomegranate juice did not meet the label declarations of 100% pomegranate. The FDA’s analyses showed that some of the samples contained undeclared ingredients (e.g., artificial colors, sweeteners, and less-expensive juices such as black currant, apple, pear, or cherry juices in place of pomegranate juice), so the products were considered adulterated and misbranded. To secure release of a detained shipment, the importer must provide evidence that the product being imported doesn’t exhibit the problem. Examples of evidence are 1) results of a third-party laboratory analysis verifying that the product has the identity and other qualifications represented on the label and 2) documentation in English showing product formulation and labeling, such as process or batch records. To be removed from the detention list, the manufacturer must demonstrate that it has resolved the conditions that gave rise to the violation.

Section 106 of the Food Safety Modernization Act calls for the FDA to promulgate regulations, including mitigation strategies, to protect against the intentional adulteration of food. The FDA will publish a proposed rule by November 30, 2013, and a final rule by June 30, 2015.

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture

The President’s Food Safety Interagency Working Group was established in March 2009, with the secretaries of the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services as co-chairs, to determine how to upgrade the U.S. food safety system. According to Richard J. McIntire, Public Affairs Specialist at the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), the working group identified improving regulatory authorities’ ability to proactively shift resources to identify and mitigate the potential economic and public health consequences of EMA events as necessary to ensure the protection of consumers from potential food-borne illness. The FSIS has been working with the FDA, the U.S. Dept. of Homeland Security, and the National Center for Food Protection and Defense (NCFPD), to address the research needs identified by the working group. McIntire pointed out that the FSIS conducts a range of activities to ensure that meat, poultry, and processed egg products are not economically adulterated, misbranded, or otherwise unacceptable and that FSIS inspectors in the 6,600 federally inspected plants each day are the first line of defense against EMA.

U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention

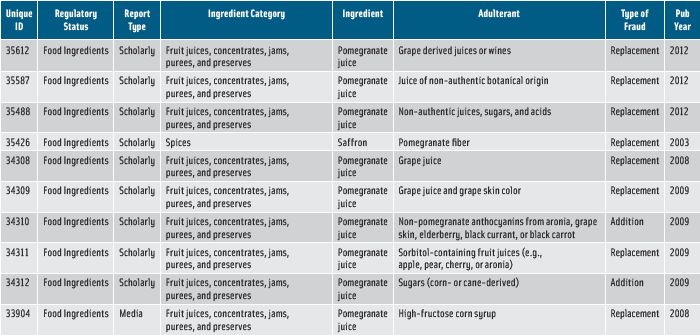

The U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention (www.usp.org), the standards-setting organization that publishes Food Chemicals Codex (FCC), formed an expert panel on food ingredient intentional adulterants in 2009 and launched its Food Fraud Database in 2012. The online database (www.foodfraud.org) is a repository for food ingredient fraud reports and related analytical methods. It includes more than 2,000 records based on more than 700 scholarly reports and 150 media reports from 1980 through mid 2012. Top ingredients represented in the database include olive oil, milk, honey, saffron, and coffee.

Jeffrey C. Moore, USP’s Senior Scientific Liaison, Food Standards, said that the database can be used by industry, regulatory agencies, and laboratories to keep a finger on the pulse of what’s happening with respect to adulteration. The database has received more than 85,000 hits on its website. The USP did a major update of the database in January 2013 and plans to continue updating it, asking for public help in reporting incidents of food fraud via the website.

USP established a skim milk powder working group in 2011 that is developing a toolbox of analytical methods, specifications, and supporting reference materials for skim milk powder, which will exclude intentionally adulterated materials, Moore said. The first proposed method coming out of this effort should be published on USP’s FCC Forum website (www.usp.org/food-ingredients/fcc-forum) for public comment by the end of December 2013. The organization expects to publish a steady trickle of additional proposed methods to fill the toolbox in the coming years. One area of intense research within the group has been on inexpensive non-targeted methods for detecting anomalies in skim milk powder. Another has been the development of a set of reference standards produced by wet-blending different levels of melamine in skim milk before spray drying. These standards mimic how real adulterated milk ingredients are likely to be produced and thus provide a better way of evaluating the performance of analytical detection methods, Moore said.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Other USP projects are focusing on natural colorants and understanding vulnerabilities of analytical methods that are routinely used. The organization also recently drafted an identity standard for pomegranate juice and posted it for public comment on the FCC Forum website. An identity standard in the FCC is not to be confused with a full FCC monograph, Moore said. The identity standard is informational and focused exclusively on identity tests and acceptance criteria. It’s a new type of standard that the USP is starting to develop for borderline agricultural raw-material ingredients that are not as well-defined or compositionally consistent as traditional food additives and ingredients.

The organization hosted workshops on food adulteration in 2009, 2011, and 2013, the most recent of which, “Economically Motivated Adulteration of Food Ingredients and Dietary Supplements,” was held September 26–27, 2013. Co-sponsored by the USP, the Institute of Food Technologists, the Natural Products Association, and the United Natural Products Alliance, the workshop featured papers by 41 speakers on a wide range of topics related to EMA of foods and dietary supplements.

National Center for Food Protection and Defense

NCFPD (www.ncfpd.umn.edu), a U.S. Dept. of Homeland Security Center of Excellence located at the University of Minnesota, has developed two databases to help address EMA: an incidents database and a susceptibility database. Karen Everstine, Research Associate at NCFPD, said that the incidents database was compiled through literature and media searches to identify characteristics of EMA incidents in food products since 1980. The susceptibility database was compiled through evaluations, by food scientists from around the globe, of about 600 FCC monographs on food ingredients not used primarily as flavors.

The susceptibility database is an attempt to catalog documented EMA events by incident, Everstine said. It can be used to get a handle on what foods and ingredients were involved, what the adulterant was, where the incident happened, where the products were distributed, the extent of the adulteration, and how the adulterators got around the regulatory systems in place. The methodology for cataloging records differs—the USP’s Food Fraud Database captures all reports on food fraud as individual records whereas the NCFPD’s database combines numerous reports from a discrete incident into one record. The databases were created with different goals in mind, she said, but both are useful in trying to determine how widespread EMA is.

The NCFPD’s databases are available on FoodSHIELD (www.foodshield.org), a web-based system for communication, coordination, education, and training among public health and food regulatory officials. Only persons actively working in some food capacity can access the databases, but the incidents database will likely be made available to the public in the near future, Everstine said. Scientists familiar with FCC monographs are invited to volunteer via FoodSHIELD to evaluate monographs for inclusion in the susceptibility database. The NCFPD is also completing EMA case studies on five food commodities to help the USDA assess the risk of those commodities.

MSU Food Fraud Initiative

Michigan State University created its Food Fraud Initiative in June 2013 to focus more directly on food fraud. John Spink, Director of the Food Fraud Initiative, said that one of its major accomplishments has been the “massive open online course” on food fraud (http://foodfraud.msu.edu) offered free to interested parties across the supply chain around the world. The two-week program features readings, a weekly two-hour lecture, and a weekly assessment quiz. More than 800 people from 48 countries participated in the first course, held in May 2013, Spink said. The next courses will be on November 12 and 19, 2013, and another will be conducted at the Food Safety Summit, April 8–10, 2014 (www.foodsafetysummit.com). The Food Fraud Initiative has also been sponsoring an annual Food Fraud Trends Conference with an associated “Food Fraud Prevention Executive Education” session. The most recent events took place in October 2013 and will be held again next spring.

Spink spoke at the Global Food Safety Initiative Conference in Spain in March 2013, at several conferences in China in June, and at several events in September in Russia hosted by the Moscow State University for Food Production, focusing on building awareness and harmonization. The collaborating groups and researchers are quickly developing and sharing best practices and using the same terms in the same way, he said.

In addition, the Food Fraud Initiative has been working with standards-setting and certification bodies and other organizations, including the Food Fraud Think Tank created by the Global Food Safety Initiative, the IFT Global Food Traceability Center, the International Standards Organization’s Technical Committee 247 on Fraud Controls and Countermeasures, and a number of USP expert panels, including the USP Dietary Supplement Adulteration Expert Panel.

Global Food Safety Initiative

The Global Food Safety Initiative (www.mygfsi.com) held a breakout session March 6–8, 2013, on food fraud during its Global Food Safety Conference, where it introduced attendees to its new Food Fraud Think Tank, a private-public collaboration of manufacturers, retailers, laboratories, supply-chain intelligence companies, and academics. The next Global Food Safety Conference will be held in Anaheim, Calif., February 26–28, 2014, and will include the session “Preventing Fraud in Your Food,” which will feature an update on the Think Tank and presentations on conducting a vulnerability assessment and effective detection and deterrence strategies.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Grocery Manufacturers Association

The Grocery Manufacturers Association (www.gmaonline.org) in January 2010 issued a report of a study titled “Consumer Product Fraud—Detection and Deterrence: Strengthening Collaboration to Advance Brand Integrity and Product Safety.” The report discussed motivational drivers for economic adulteration; the structural weaknesses at both industry and government levels that inadvertently created opportunities for economic adulteration to thrive; and recommendations for industry, government, suppliers, and retailers.

Institute of Food Technologists

The Institute of Food Technologists (www.ift.org) has addressed food adulteration through the years via numerous symposia and research papers presented at its IFT Annual Meeting & Food Expo, publication of articles in Food Technology magazine, research papers published in Journal of Food Science, and reviews published in Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. It also recently co-sponsored the USP workshop “Economically Motivated Adulteration of Food Ingredients and Dietary Supplements.”

What Companies Are Doing

Instrument manufacturers and other laboratories offer information on use of their instruments and services in detection of adulteration. Here are some examples.

• Agilent Technologies Inc. (www.agilent.com) offers, among other things, a brochure on assessing food quality, information on a dilute-and-shoot gas chromatography/mass spectrometry method for the analysis of olive oils that avoids tedious sample preparation steps, and an application note on screening and measurement of adulterant levels in bovine milk by mid-Fourier-transform near-infrared spectrometry (FT-NIR).

• Neogen Corp. (www.neogen.com) recently began offering a raw or cooked meat species identification service called NeoSeek™ that utilizes a DNA-based assay featuring specialized PCR technology to detect adulteration in horse, pig, poultry, beef, or sheep meat. The service complements the company’s Food Analyte Screening Test (F.A.S.T.) immunostick test kits designed for use in processing facilities.

• PerkinElmer Inc. (www.perkinelmer.com) offers a webinar on screening food for adulterants and contaminants with a direct sample analysis (DSA) system combined with a time-of-flight mass spectrometry system. It uses the AxION DSA system as an alternative to front-end gas or liquid chromatography systems. Among the examples discussed are olive oil adulterated with soy oil, natural vanilla adulterated with synthetic vanilla, and pomegranate juice adulterated with grape juice. The company also offers an application note on rapid detection of adulteration of vanilla bean extract with tonka bean extract, which is banned because it contains coumarin.

• Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (www.thermoscientific.com) offers, among other information, a webinar on adulteration testing of edible oils by FT-NIR.

• Waters Corp. (www.waters.com) offers an application note illustrating how its Acquity ultra-performance liquid chromatograph in combination with mass spectrometry for detection, chemometric software, and database searching can identify differences among pomegranate juice samples.

Challenges Ahead

Everstine said that the biggest challenge ahead is to detect EMA without relying on testing for multiple adulterants throughout the supply chain for food products—in other words, to develop a type of early warning system for heightened potential of EMA in a food product so that laboratory and inspection resources can be targeted toward the riskiest food products. The recent horse meat incident is a good example, she said; a lot of DNA testing was implemented after the incident, but it’s not realistic to do it all the time at all points in the supply chain.

Moore said that a critical challenge is connecting the dots between food fraud and its impact on public health and safety. Most often, there are no public health or safety problems with an adulteration, but other times it can be very serious. Adulteration doesn’t fit into the traditional risk-assessment model, he added. Since companies and regulators have finite resources for managing risks associated with EMA, guidance standards for identifying the most risky or vulnerable areas are needed and could help to focus those resources in a risk-based framework. Other challenges are to develop better analytical methods to ensure that they can detect a priori unknown adulterants through non-targeted anomaly-detection approaches and to develop appropriate matrix-matched reference materials to evaluate the performance of analytical methods aimed at detecting adulteration.

Spink said that the biggest challenge is that the bad guys are stealthy and actively seeking to avoid detection. They will be patient, wait for an opportunity, innovate, and then attack. They are often very creative, disciplined, and very well-funded. On the other hand, many are just sloppy and not that complex in their attacks. The industry needs to balance resources to combat both types of criminals, he added. One way to reduce the public health threat while conserving time and dollars is to focus on prevention, he added. When agencies and initiatives really try to understand how and why a specific adulterator attacked a specific product, he said, they can research ways to reduce that specific attack and implement broader systems that reduce the opportunity for fraud.

Pertinent Reading

“Defining the Public Health Threat of Dietary Supplement Fraud,” by Virginia M. Wheatley and John Spink, in the November 2013 issue of Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety

“Economically Motivated Adulteration (EMA) of Food: Common Characteristics of EMA Incidents,” by Karen Everstine, John Spink, and Shaun Kennedy, in the April 2013 issue of Journal of Food Protection

“Modern Analysis of Chemical Contaminants in Food,” by Katerina Mastovska, in the February/March 2013 issue of Food Safety

“Understanding and Combating Food Fraud,” by John Spink and Douglas C. Moyer, in the January 2013 issue of Food Technology

“Development and Application of a Database of Food Ingredient Fraud and Economically Motivated Adulteration from 1980 to 2010,” by Jeffrey C. Moore, John Spink, and Markus Lipp, in the April 2012 issue of Journal of Food Science

“Defining the Public Health Threat of Food Fraud,” by John Spink and Douglas C. Moyer, in the November 2011 issue of Journal of Food Science

“Screening for Adulterants,” by Neil H. Mermelstein, in the September 2011 issue of Food Technology

“Preventing the Adulteration of Food Protein,” by Jeffrey C.Moore, Markus Lipp, and James C. Griffiths, in the February 2011 issue of Food Technology

“Analyzing for Melamine,” by Neil H. Mermelstein, in the February 2009 issue of Food Technology

“Testing for Adulteration” by Neil H. Mermelstein, in the July 2008 issue of Food Technology

Neil H. Mermelstein,

Neil H. Mermelstein,

a Fellow of IFT,

is Editor Emeritus of Food Technology

[email protected]