Chef Michael McGreal: Drill Sergeant and Veggie Ambassador

CULINARY POINT OF VIEW

Michael's Recipe: Roasted Beet and Mixed Berry Sorbet

While pursuing a degree in veterinary medicine, Michael McGreal got a job in campus foodservice to pay the bills. Little did he know, that job would lead him to his true calling—culinary. His strict but inspiring professors at culinary school left an indelible mark on McGreal, who, when offered the chance, became an instructor himself. Now Chef McGreal is the Culinary Arts Dept. Chair at Joliet Junior College in Joliet, Ill.Much like a drill sergeant to the enlisted, McGreal hammers his students with skills they will need in the restaurant world. He not only teaches proper knife techniques to budding chefs, he also works with the Michelle Obama Chefs Move to Schools campaign to impart local elementary children with how delicious and nutritious vegetables and fruits can be.

Kelly Hensel: How did you go from studying veterinarian medicine to culinary arts?

Michael McGreal: I grew up in a family where we had pets and I was always the neighborhood kid who people would call when they got a squirrel stuck in the chimney or a snake in the basement. I just loved animals and I thought I could really see myself taking care of animals and doing the veterinarian medicine thing. So, when I graduated from high school, I registered in a pre-vet program at Northern Illinois University. My parents had always stressed the idea that you work to make a living, so I got a job in foodservice in the dorm where I lived.

I had never worked in a restaurant before, and so I started out as the milk runner. Apparently, I did that job well because after a month, they made me a food runner instead and I was one that would refill, change, and monitor the serving lines. After a month or so doing that, they moved me up to a cook’s helper. Then, a year and half later, I became one of the banquet cooks for the college. Working in a big facility, we would get up to 10,000 people at one time with banquets.

When the banquet chef retired, I decided to take the civil service exam and I became the new banquet chef for all of NIU.

Hensel: And all the while, you were still studying veterinarian medicine?

McGreal: Yeah, for the first year and a half I was. But I found that I really loved working in the food industry—the food production and customer service part of it. Seeing people love the food that you produced.

It just became very natural to me and it was easy for me to get good at, and I found a niche for myself. So, after about a year and a half I stopped with the pre-vet courses and just tried to take other college course work to see if I liked anything else. The idea of actually being a chef really didn’t occur to me. I looked at my foodservice job as a way to pay bills at the time.Then, after being the banquet chef for about two and a half years, I was talking to my parents on the phone one night and my dad asked, “Did you decide what you’re going to do with college since you’ve been there for five years?” I told him that I thought I was narrowing it down but I wasn’t positive yet. He suggested I pursue a career as a chef, since I seemed to be good at it. I said, “Well that’s a great thought.” I enrolled at a culinary school at Washburne—known as Washburne Trade School at the time—which was one of the top culinary schools back then. I got in the program, fell in love with it, and never looked back.

Hensel: Since you had experience working as the Banquet Chef at NIU, did you find that you already knew the basics when you started studying culinary at Washburne?

McGreal: You know it was really a great learning process. And I say that because even here at Joliet Junior College, we’ll have people that may have been cooks in the industry for a while and they just want to get the degree so they can move up the ranks. A lot of them start here thinking that they already know a lot. But when I went to culinary school, many of the techniques that I thought I was so proficient at were really the least desirable skills or the quick and dirty ways of getting something done. As a cook coming up through the industry and not going to formal training you’re really learning people’s bad ways of doing things and the things that they try and do when nobody’s looking to get the job done more quickly.

I learned that there were so many better ways to do things. By using proper techniques, you will have a finished product that builds on flavors rather than just throwing things in a pot. For example, many restaurants might make a French onion soup but really they are just throwing everything in a pot of water, boiling it, and adding some caramel coloring or something at the end to make it brown. It’s just boiled onion soup. But, when you caramelize those onions first to make the sugars caramelize you start building on amazing flavors. That’s really the food science part of being a chef.

Anybody can throw ingredients together. Anybody can throw broccoli in a pot and thicken it with something and say it’s cream of broccoli soup, but by sweating down celery, onion, and garlic ahead of time and then adding the broccoli enables you to build such incredible intense flavors that wouldn’t have been there by just boiling them.

I think that is the neat thing now with our industry—chefs that are not food scientists, I think we’re realizing the value that when we do anything we need to really prepare it right. It’s about applying a science-based method to it to make it turn out in an optimal way.

Hensel: How did you decide education was where you wanted to take your culinary career?

McGreal: Well you know that I worked while I went to culinary school at Washburne. The instructors I had there were very strict chefs. And I came in as this kind of cocky guy since I’d been working in the industry as a banquet chef already. I thought I knew everything and I thought I was just going to get this degree. I quickly learned that, like I said earlier, a lot of the skills I had learned were not the proper ways of doing things. Or the best ways.

These chefs they were strict about it. I remember my first day of class in culinary school I was sitting next to this girl and talking to her and the teacher pointed to me and he said, “Hey Romeo, this isn’t a dating school, get out of my class.” He threw me out of class. Well, I stood in the hallway and thought I’m not going home. And I waited until he gave them a lunch break and then I went back in and apologized and swore to him it would never happen again. He told me that when I came back into the classroom he wanted to see attention to detail and focus. By the end of the class, I became his go to student. He became a great mentor to me. Some of the other chefs in the program were also very strict but extremely great chefs and great instructors.

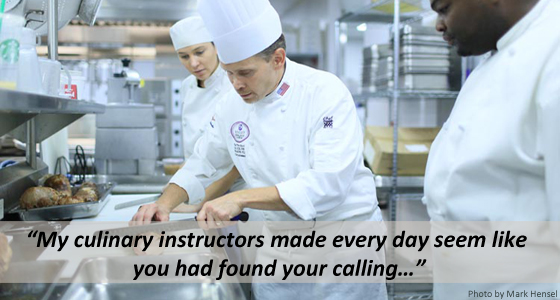

After I graduated, I worked in industry and ended up having a restaurant in the south side of Chicago for six years. One day my mother called me up at the restaurant and said, “Didn’t you say that someday you would like to teach?” I said yeah because I told her about how these teachers were great and someday I could see doing that. These culinary instructors made every day seem like you had found your calling. They were able to make me get up every day excited to go to school. I knew that was something that I wanted to hopefully try and have that effect on somebody down the road.

So, when my mom called I said yes I always thought it would be a good thing to do. She told me she saw in the paper that Joliet Junior College was looking for a full-time tenured track chef instructor. I contacted the school and went through a grueling three-day interview process, in which I had to cook for the chefs and give a lecture. After a final interview with the vice president of the college, they offered me the position. That was in 1996.

Hensel: You’ve written some textbooks, one of the being Culinary Math. From your perspective, do you think people know how much math and science are involved in culinary and cooking?

McGreal: It’s funny that you say it Kelly because many times we have traditional college-age students that are recent high school graduates and they come in with their parents. The parents will tell us that their son or daughter is excited to study culinary and one reason is that they hate math and science.

I think that’s where cooking shows, like the popularity of Food Network, comes in because home cooks can compete and then be named a “master chef.” These shows give a false reality to people coming into culinary programs where they get to thinking that it’s just the neat stuff. That was kind of like my experience with vet school. I wanted to take care of the puppies and take care of the sick bird that fell out of tree type of thing and there’s a lot of more work before you get to do that stuff.

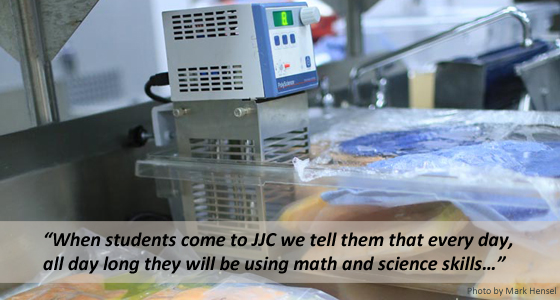

When students come here [Joliet Junior College Culinary Program] we tell them from the first day, every day, all day long you are using math skills and every day, all day long, you are using science skills. Whether it’s the angle of your knife to the steel to hone it every time you pick it up to cut a carrot. Or it’s cutting up carrots on the board and then moving on to cut other things and how this can cause cross contamination possibilities.

I wrote the math book because I see there’s a huge discrepancy between the generations of chefs from a few generations ago where everything was about food cost, waste and loss, and yield and percentages. You know every penny was important. I do speaking engagements across the country and one of them is called “Every Ounce Counts.” I talk about how chefs can become so bogged down with meetings, paperwork, hiring, firing, and interviewing that they forget to make sure they are using every last bit of mayonnaise from the jar—making sure every ounce is accounted for. And we wonder why so many restaurants fail in America.

I think the beauty of students coming to culinary school instead of just working their way up in industry is that we really teach them the by-the-book way of doing it so that when they get out of here hopefully important things like sanitation or cross contamination or HACCP are engrained into the way they operate.

Hensel: You touched on the idea that celebrity chefs are affecting people’s decision to go into culinary. Is this phenomenon affecting your school’s attendance numbers? And, are these students surprised when they realize the minutia of skills they have to learn?

McGreal: We do have many people that see that on TV and they get here and the first day of school they’re not cooking, they’re sitting in a classroom and we lecture all day and talk about the industry in general.

I equate it to the guy who signs up for the military and he’s so proud and he gets on the bus that first day to go to the base. My brother was a drill sergeant and he says it was funny because they’d get on the base and there are billboards as you drive in that say “So Proud,” “Be Strong,” “American Pride.” And so as you’re driving in you’re so excited to get to this theme park called basic training and then once you get off the bus, the drill sergeant shouts “All right you sissy’s get off the bus.” They get you so excited as you drive in just so they can crash you once you get off the bus to bring you down to ground level. I think in a way good culinary schools do that. We hit the brakes when you first come in and give you a reality check.

If you think you are going to be on Food Network and have your own show in two months, this is not the right field for you. You’re going to be working weekends, nights, and holidays and when you’re friends are at a wedding, you’re still in the restaurant.

We try to give them a good idea of what to expect. I think you’ll see that the retention rate of students is definitely not going to be near 100%. What happens is they come in with this idealized view that it’s really exciting to be a chef. They get here and realize that in order to get to the top there are many bumps along the way—a lot of hours to put in. I think we see that they come in with kind of the misconception of glamour of the industry.

But after about a month or so, the ones who really want it and who are really excited about it for what it really is, they are so driven that it’s almost as if you lit a fire under them. And they are blazing now ready to keep going. And then maybe 10% are thinking what did I get myself into.

Hensel: Well obviously, the program at JJC is doing well. This summer JJC went to Las Vegas where your school won both the American Culinary Federation’s Student Team National Championship and the Student Chef of the Year.

McGreal: Yeah that’s right.

Hensel: Congratulations. Has JJC been participating in these competitions for a while? Has the school won these two awards before?

McGreal: Well, the college competed a lot back in the 1980s. And we did win a bunch of awards in national and international competitions during that time. Then, during the early ‘90s, we stopped doing it. We refocused and restructured the program, which we needed to do.

We are actually the fourth oldest culinary school and there are probably about 5,000 culinary schools in the United States. So, we have a great history of just good education. As a community college, we have a great history of fundamental culinary training, not the fluff and stuff that maybe some other schools might do, where they want to keep students enrolled in a private or for profit school at a real high tuition rate. They might offer some fancier classes instead of really focusing on the fundamentals.

We drill sergeant them from day one. You can’t move on until your knife skills are advanced enough to move on to a second class or your cooking methods are right to move on to a second class. We require what industry is going to require of our students.

And so we won both of those competitions this year but what’s really exciting is that for the past 12 years we’ve been the state of Illinois champions in culinary competition. And for five of the past six years we’ve been the Central United States champions, from 15 states in the central U.S. And then two years ago, we went to the competition in the final four for the best in America again and we actually won both of these competitions—we won the Student Team National Championship and the Student Chef of the Year.

Hensel: You are involved in Michelle Obama’s Chefs Move to Schools initiative. Can you talk about how were you chosen, and what kind of activities you have been leading and participating in?

McGreal: It’s one of the neatest things. I think for multiple reasons—not just because of being able to go to the White House but to be able to work with kids and schools to try to get kids healthier in America has just been a moving and exciting experience. I think it was in 2010 that Michelle Obama worked with the American Culinary Federation and some other chef organizations to get some chefs down to the White House. The major specification was they had to be chefs that work with kids and schools already, and are really committed to this whole initiative of getting kids healthy. My colleague Kyle Richardson and I were chosen from the Central United States to go to the White House. Michelle Obama came out and she talked about the importance of getting kids healthy and getting our schools to ensure that they’re serving good healthy meals. She said that next to grandma, chefs are the experts on food in America and so there’s nobody that could connect with our kids about what to eat better than chefs could.

I was appointed the Central U.S. Liaison for the Chefs Move to Schools, and I’m also the National Education Chair for the Chef & Child Foundation with the American Culinary Federation. So, I’ve been working with the local school systems.

At Eisenhower Elementary, I had all the kids for assembly, and I did healthy cooking demonstration where the kids helped me cook and ate what I made. We made butternut squash bisque and the kids were going nuts for it. They thought it was the best thing. The teachers were laughing at me because they couldn’t believe I got them to eat squash soup. It’s such an emotional and moving experience. As a chef right now, I think that’s one of the great things about the popularity of cooking television shows—it has given chefs a celebrity-type status. With kids, it used to be the firefighters and police officers coming in that got kids excited. But now for a chef to walk into a classroom, it’s as if you could hear a pin drop, the kids are all excited.

It’s exciting to talk to them about eating fruits and vegetables and to make things for them that they are scrambling to try.

Hensel: When you are working with kids, have you found that they don’t know what some of the fruits and vegetables are that you are telling them about?

McGreal: Oh, yeah. Even to bring in something like a tomato. I’ll say to the kids, “Do you know what this is?” And some of them will think it’s an apple. And I will tell them it is a tomato and then ask them where a tomato comes from. Some kids will say trees. So, we’ll cut it up, we’ll do different things with a tomato, and as the kids try it, probably 90% of the kids when you cut something up, they like it. Or, I’ll cut a piece of broccoli up. The kids, they look at it as if they have no clue what that big bunch of green is that you have. And right away, they will say its flowers. When I cut it into little pieces, a majority of the kids will taste it and think it is pretty good.

One of the things I make with the kids is a beautiful purple sorbet. I’ll talk about it a little and bring one kid up let him taste it. Once he likes it, and I ask if anyone else wants to try it, all the hands are up. So, I make a batch of it with the kids’ help. They all have to put a rubber glove on. Each kid grabs a handful of frozen blueberries, puts it in a blender, they grab a handful of frozen strawberries throw it in a blender, and then some frozen raspberries. Then I grab the bowl of fresh roasted beets out from under the table and they look at it like “yuck.”

And I remind them that they just tried and liked my sorbet, so they grab a handful of roasted and quartered whole beets, and throw those into the blender. We add a big bunch of mint, a little chunk of fresh ginger, and a squeeze of honey for a little bit of sweetness to take some of the citrus out of those berries. Finally, we puree it. It is the silkiest, most beautiful purple fruity sorbet and it tastes like fruit. While they are eating it, I tell them about what a beet is. When I ask how many kids like beets, all of their hands go up. They now know what beets are and that they can taste good.

McGreal: I look at the industry and some of the things that are out there right now, such as chefs incorporating some molecular gastronomy into food, and I don’t know if they are fads and are going to fade away. But the really cool thing about it is that it has merged culinary with food science. All these molecular gastronomy chefs have opened the eyes of the typical restaurant chef and hotel chef to say that it’s not just about making a good chicken piccata for a wedding or something like you’ve made for years. The knowledge and techniques that we have, as chefs, are fundamentally all science based. Whether it’s caramelization of onions or it’s the sous vide cooking that people think of as this very slow and low cooking, it’s all a process of being able to cook it the right way to control bacteria and have ideal results.

So, for chefs around the globe to realize that we are only really as good as the science applications that we are using—that’s what cooking is about and what food production is about. Our having knowledge of food science and food safety—all the things that an organization like IFT is about—will make us successful chefs and make us better prepared to be safe food producers in America. I think that’s going to be the whole trend of our industry now, whether it’s farm to fork, sustainable agriculture, HACCP, food safety, or preventing bioterrorist food things. It has made us all aware in the food industry that in a way you guys [food scientists and technologists] are the foundation of who we are and who we want to be. And so our growth really depends on us gaining knowledge from an organization like IFT, from food scientists, and people who know the origins of food, so we can make that food better. Whether it’s the field to consumer, or how to cook it and actually have the food react better to heat.

I think that’s going to be the future of our industry and culinary education. It’s not just the traditional “let’s make a pot roast.” It’s going to be: Why does meat taste this way when it’s seared in a pan? Why does the texture of connective tissue break down under this slow moist combination cooking? It’ll be the why rather than the how.

Roasted Beet and Mixed Berry Sorbet

Yield 8 Servings

Ingredients

2–3 oz fruit juice

1/2” knob of fresh ginger, peeled

1 small/medium fresh beet pre-roasted and cooled

1 ½ tbsp honey

¼ tsp lemon juice

6 fresh mint leaves for the sorbet

1 ½-lb mixed assorted frozen berries (removed from freezer for 10 minutes)

6 fresh mint leaves for garnish

Steps

- Place fruit juice, ginger, beet, honey, lemon and ½ of mint (6 leaves) in blender and puree for 5 seconds.

- Add frozen fruit and puree until smooth.

- Serve with a spring of fresh mint.