Fat and Hungry: Are U.S. Food Policies Obesogenic?

U.S. food policies may have led to unexpected paradoxes when it comes to overweight and obesity.

Food insecurity is generally defined as inconsistent access to sufficient amounts of food for an active, healthy life. In certain parts of the world, it is very easy to identify which individuals experience food insecurity: Food insecure individuals in poor regions such as sub-Sahara Africa and Southeast Asia usually have low body mass indexes and appear thin, underweight, and malnourished. Moreover, their inconsistent access to food is limited to rice, beans, potatoes, and locally grown vegetables and fruits, and most of what they eat must be cleaned, peeled, and cooked.

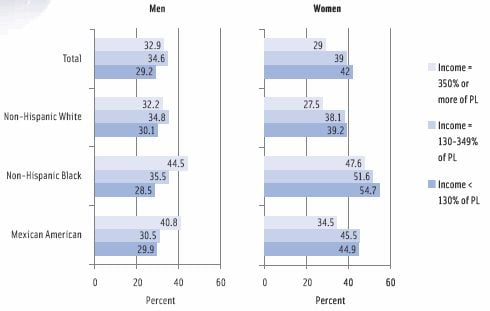

However, in the United States, individuals experiencing food insecurity are not as obvious: Such individuals often have high body mass indexes and appear overweight or obese. In addition, they are frequently the beneficiaries of U.S. food assistance programs and rarely spend considerable time preparing and cooking their meals (i.e., they have unrestricted access to convenience foods). To be sure, overweight and obesity are increasing in the United States in general, but recent data indicate that these issues are more prevalent among individuals with low socioeconomic status and low educational level—in particular, women and children (DeSilver, 2013; NRC and IOM, 2013; OECD, 2013). These tend to be the individuals benefitting most from the following U.S. food assistance programs: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); National School Lunch Program (NSLP); School Breakfast Program (SBP); and Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC).

A Hefty Arrangement

SNAP, the largest U.S. nutrition assistance program, provides resources to low-income people for the purchase of eligible food to prepare nutritious, low-cost meals (USDA, 2014). The U.S. Dept. of Agriculture (USDA) identifies food eligible for purchase through SNAP as breads and cereals; vegetables and fruits; meat, seafood, and poultry; and dairy products. The program prohibits the purchase of alcoholic beverages, tobacco products, vitamins, and medicine but permits the unrestricted purchase of soda, candy, cookies, potato chips, snack crackers, and unhealthy, calorie-dense convenience foods. WIC avails similar dietary staples to low-income pregnant and post-partum women and their children up to age five. Prior to a recent overhaul of the meals available through the NSLP and SBP, children routinely dined on pizza, hamburgers, French fries, soda, flavored milk, and sugary cereals. Very little in the form of micronutrient-dense whole vegetables and fruits was available for breakfast or lunch. Now that the NSLP and SBP serve more vegetables and fruits, many children choose not to purchase them or throw them away (Chasmar, 2013; CBS News, 2013).

The USDA Food and Nutrition Service, which administers SNAP, WIC, NSLP, and SBP, states that it works with state agencies, nutrition educators, and neighborhood and faith-based organizations to ensure that those eligible for food and nutrition assistance will make healthy choices and choose active lifestyles. These efforts include the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the MyPlate dietary tool, both of which emphasize the importance of eating a variety of vegetables and fruits and ensuring they make up at least half of each meal; a SNAP recipe database (http://recipefinder.nal.usda.gov); and tips for buying healthy foods on a budget (e.g., "Eat Right When Money's Tight" a webpage on the USDA's SNAP website).

The USDA Food and Nutrition Service, which administers SNAP, WIC, NSLP, and SBP, states that it works with state agencies, nutrition educators, and neighborhood and faith-based organizations to ensure that those eligible for food and nutrition assistance will make healthy choices and choose active lifestyles. These efforts include the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the MyPlate dietary tool, both of which emphasize the importance of eating a variety of vegetables and fruits and ensuring they make up at least half of each meal; a SNAP recipe database (http://recipefinder.nal.usda.gov); and tips for buying healthy foods on a budget (e.g., "Eat Right When Money's Tight" a webpage on the USDA's SNAP website).

Despite these guidelines and advice, economically deprived people tend to spend less on vegetables and fruits and more on calorie-dense convenience foods that are high in calories, fat, sodium, and added sugars as well as on meats and meat products (Sturm, 2009; FRAC, 2011). It therefore seems that low-income people routinely use SNAP, NSLP, SBP, and WIC benefits to purchase and consume high-fat, high-sodium, calorie-dense foods. To be fair, the tendency to avoid eating vegetables and fruits is not unique to low-income populations. For all Americans, regardless of socioeconomic level, the consumption of vegetables and fruits is low: U.S. adults eat vegetables approximately 1.6 times per day and fruits 1.1 times per day even though researchers indicate that diets high in vegetables and fruits lower the risk of obesity (CDC, 2011; CDC, 2013).

Obesity is the leading preventable cause of illness and a significant risk factor for chronic disease. The prevalence of obesity among low-income individuals has led to some startling health statistics. The rate of type 2 diabetes among individuals in food-insecure households in the United States is 50% higher than that among individuals in food-secure homes. Researchers believe a strong reason for the increased association between food insecurity and type 2 diabetes is that people receiving benefits from U.S. food assistance programs are substituting “inexpensive carbohydrates, such as refined starches,” for the dietary intake of fruits and vegetables (Seligman et al., 2010). This increases blood glucose levels and may subsequently lead to a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes or other metabolic issues. Other chronic diseases associated with obesity, such as cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, osteoarthritis, and certain forms of cancer, are also more prevalent among low-income individuals on U.S. government food assistance programs, and their health outcomes are worse because they cannot afford adequate health care on their own (Rutten et al., 2012; NRC and IOM, 2013).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Snags in U.S. Policies

Snags in U.S. Policies

Obesity accounts for a 42% decrease in the life expectancy of American females and a 67% decrease in the life expectancy of American males (Preston and Stokes, 2011). Moreover, obesity and weight-related illnesses increase healthcare spending by $190 billion a year; this exceeds the healthcare cost of tobacco smoking (Begley, 2012). Having realized the adverse impact obesity has on morbidity, mortality, and the meteoric rise in the cost of health care, U.S. policymakers have tried several food-based tactics to stem the tide of obesity.

In 2013 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced its proposal to remove partially hydrogenated oils (i.e., trans fats) from the list of generally-recognized- as-safe foods, and lawmakers in some U.S. cities have outright banned the use of trans fats in food sold in restaurants and school cafeterias. New York City passed an ordinance banning the sale of supersized sugary fountain beverages, which has since been overturned, and the mayors of Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco, and 13 other major cities have formally asked the U.S. Congress to discontinue the practice of allowing the purchase of soda and other sugar-sweetened beverages with food-assistance benefits (CBS/AP, 2013). In addition, various city and county governments have proposed higher sales taxes on items such as candy, soda, potato chips, and other items classified as junk food.

The problems with these and other policy-level measures such as nutrition labels and mandates for calorie counts on menus, smaller portions, and reduced sodium content are numerous, but a few are more noteworthy than others. One obvious problem is that most regulatory measures take a blanket approach, penalizing not only low-income people receiving government food assistance but also middle- and high-income citizens who are not enrolled in food assistance programs and may not even be overweight or obese.

Another issue is that policy-based interventions fail to take into account the cultural, social, and psychological factors that dictate which foods consumers eat and how much they eat. For example, because parents in food-insecure households are often concerned about having sufficient food and not wasting it, they may overeat when food is available and advise their children to do the same—even if their children are full. This clean-your-plate strategy teaches low-income children to ignore innate satiety cues, and they may continue this practice through adulthood (Rutten et al., 2012).

In addition, adults and children in low-income households—many of which are comprised of ethnic minorities—may regularly consume traditional cultural or ethnic meals that are high in calories, fat, and sodium or meals that require the least amount of preparation and cooking (i.e., convenience foods) (Saslow, 2013). For example, a recent study suggests that low-income mothers on U.S. food assistance programs do not know how to prepare and cook vegetables and fruits (Chen and Gazmararian, 2014); such preparation and cooking skills would facilitate greater consumption of wholesome low-calorie meals. Clearly, low-income families are more concerned with eating food that is filling and familiar rather than nutritious.

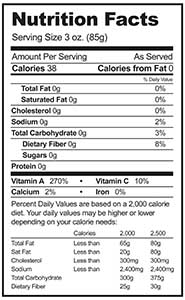

Another significant dilemma is the substantial resources U.S. policy makers have invested in educational interventions aimed at motivating low-income individuals to change their behavior. The educational tools include websites (such as the aforementioned “Eat Right When Money’s Tight” webpage), dietary guidelines, nutrition labels, serving-size information, and calorie counts on menus at fast food restaurants. These efforts—which rely on consumers to read, increase awareness and understanding, and take action—have largely been ineffective: Studies reveal that all consumers, regardless of income level, ignore calorie counts on menus and either disregard serving sizes or fail to comprehend what they mean (Graham and Jeffrey, 2011; Elbel et al., 2013; Jalonick, 2014). Furthermore, height, weight, and level of physical activity vary from person to person, making it difficult or impossible to determine whether a daily dietary intake of 2,000 calories, as suggested on nutrition labels, is excessive, sufficient, or inadequate—especially for individuals with low math and reading skills. On the other hand, studies indicate that health-claim messages on packaging and advertisements, which the U.S. government regulates but does not utilize, influence consumers considerably. Thus, any food marketed or otherwise perceived as convenient and nutritious, even if it is not, receives consumer attention.

Another significant dilemma is the substantial resources U.S. policy makers have invested in educational interventions aimed at motivating low-income individuals to change their behavior. The educational tools include websites (such as the aforementioned “Eat Right When Money’s Tight” webpage), dietary guidelines, nutrition labels, serving-size information, and calorie counts on menus at fast food restaurants. These efforts—which rely on consumers to read, increase awareness and understanding, and take action—have largely been ineffective: Studies reveal that all consumers, regardless of income level, ignore calorie counts on menus and either disregard serving sizes or fail to comprehend what they mean (Graham and Jeffrey, 2011; Elbel et al., 2013; Jalonick, 2014). Furthermore, height, weight, and level of physical activity vary from person to person, making it difficult or impossible to determine whether a daily dietary intake of 2,000 calories, as suggested on nutrition labels, is excessive, sufficient, or inadequate—especially for individuals with low math and reading skills. On the other hand, studies indicate that health-claim messages on packaging and advertisements, which the U.S. government regulates but does not utilize, influence consumers considerably. Thus, any food marketed or otherwise perceived as convenient and nutritious, even if it is not, receives consumer attention.

Perhaps the most obvious glitch with policy-level measures to address obesity is that they place enormous blame and responsibility on the food industry. Over the past 10 years food companies have cut calories, reduced portion sizes, and lowered the levels of fat, sodium, and sugar in the products they offer, yet the U.S. obesity epidemic persists. In addition, fresh, frozen, and canned vegetables and fruits as well as rice, beans, and other nutritious low-calorie fare are plentiful in U.S. supermarkets across the country at affordable prices: Indeed, researchers have determined that eating a healthy diet costs $1.50 more per day than eating a diet comprised mainly of unhealthy foods (Rao et al., 2013).

Maybe food and the issues related to its availability, cost, and consumption are not the principal cause of obesity: According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the obesity epidemic is the result of a complex combination of factors, some of which are as follows: the supply and availability of food changed dramatically in the second half of the 20th century, the price of calories reduced significantly, convenience foods became widely available, the time available for traditional meal preparation shrank considerably, jobs have become largely sedentary, and more women participate in the work force (Sassi, 2010). Besides these issues, the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine identify urban development strategies determining the location of supermarkets and fast food restaurants and the marketing of electronic devices to children as other elements that help create an obesogenic environment (NRC and IOM, 2013).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Alternative Approaches

This complex web of factors make it unlikely that U.S. food assistance policies directly contribute to the United States’ status as having the highest rate of overweight and obesity among high-income countries. Low-income people receiving government benefits may be “responsible for their individual behaviors, but individual lifestyles are also influenced by the policies adopted by communities, states, and national leaders” (NRC and IOM, 2013). Accordingly, other U.S. policies that bear some responsibility for the obesity epidemic are agricultural subsidies, transportation policies that discourage public transport, urban planning that eliminates paths for walking and other physical activity, and segregated urban areas that promote unhealthy diets and lifestyles (Sassi, 2010). The OECD estimates that policy interventions to improve diet and increase physical activity may reduce expenditures on obesity-related chronic diseases by only 1%, which is why other approaches—such as better urban planning; increased public transportation; improving work environments, the duration of the work week, and wages; and stricter management of food-assistance benefits—must be included.

With more than two-thirds of the U.S. population being either overweight or obese, the problem of excess weight affects people of all socioeconomic backgrounds. Yet statistically, obesity is more prevalent among low-income people. SNAP, WIC, NSLP, and SBP may not be the cause of obesity in low-income households, but these programs certainly enable the overconsumption of obesogenic foods and perpetuate the pattern by essentially subsidizing the purchase and consumption of unhealthy food.

Obesity in the United States: A Perplexing Issue

The United States is the most overweight and obese high-income country, but the statistics on overweight or obesity in the United States challenge conventional wisdom. American men become more obese as their income level rises whereas American women become less obese as their income level rises. Consequently, low-income women and children of all racial and ethnic backgrounds are the most overweight and obese Americans, and the least overweight and obese Americans are low-income black men (and all Asian-Americans). An informal survey of employed and unemployed low-income black men in Chicago, Ill., yields two possible reasons for the disparity: 1) they receive fewer food-assistance benefits than low-income women who have children and 2) low-income black men are more likely to have jobs that require physical activity for most of the day (i.e., non-sedentary manual-labor jobs). In essence, low-income black men eat less because they have fewer funds to buy food and move around more than most other segments of the U.S. population.

Another revelation is that whether or not low-income individuals live in food deserts (i.e., areas with inadequate access to grocery stores) does not appear to be a significant cause of obesity. A nationwide study confirms this, indicating that obesity rates are similar among low-income individuals who live near supermarkets and those who do not:

| Low-income and low-access |  |

rate of obesity: 30% |

| Low-income only |  |

rate of obesity: 28% |

| Low-access only |  |

rate of obesity: 25% |

| Neither |  |

rate of obesity: 26% |

Toni Tarver

is Senior Writer/Editor for Food Technology magazine

[email protected]

References

Begley, S. 2012. As America’s waistline expands, costs soar. Reuters, April 30. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/04/30/us-obesity-idUSBRE83T0C820120430. Accessed Jan. 31, 2014.

CBS/AP. 2013 Limit food stamps for sodas, 18 mayors ask government. CBS News, June 19. http://www.cbsnews.com/news/limit-food-stamps-for-sodas-18-mayors-askgovernment/. Accessed Jan. 31, 2014.

CBS News. 2013. Michelle Obama-touted federal healthy lunch program leaves bad taste in some school districts’ mouths. CBS News, August 30. http://www.cbsnews.com/news/michelle-obama-touted-federal-healthylunch-program-leaves-bad-taste-in-some-school-districtsmouths/. Accessed Jan. 31, 2014.

CDC. 2011. Strategies to prevent obesity and other chronic diseases: the CDC guide to strategies to increase the consumption of fruits and vegetables. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga. http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/fandv_2011_web_tag508.pdf. Accessed Jan. 31, 2014.

CDC. 2013. State indicator report on fruits and vegetables, 2013. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga. http://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/downloads/State-Indicator-Report-Fruits-Vegetables-2013.pdf#page=3&zoom=auto,0,556. Accessed Jan. 31, 2014.

Chasmar J. 2013. Indiana school district loses $300K because students refuse to buy first lady’s healthy meals. The Washington Times, July 11. http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2013/jul/11/indiana-school-district-loses-300k-because-student/. Accessed Jan. 31, 2014.

Chen, D.Y. and Gazmararian, J.A. 2014. Impact of personal preference and motivation on fruit and vegetable consumption of WIC-participating mothers and children in Atlanta, Ga. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 46(1): 62–67.

DeSilver, D. 2013. Obesity and poverty don’t always go together. Pew Research Center. November 13. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/11/13/obesityand-poverty-dont-always-go-together/. Accessed Jan. 31, 2014.

Elbel, B., Mijanovich, T., Dixon, L.B., et al. 2013. Calorie labeling, fast food purchasing and restaurant visits. Obesity 21(11): 2172–2179.

FRAC. 2011. A review of strategies to bolster SNAP’s role in improving nutrition as well as food security. Food Research and Action Center, Washington, D.C. http://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/SNAPstrategies.pdf. Accessed January 31, 2014.

Graham, D.J. and Jeffery, R.W. 2011. Location, location, location: eye-tracking evidence that consumers preferentially view prominently positioned nutrition information. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 111(11): 1704–1711.

Jalonick, M.C. 2014. FDA to revise nutrition facts label. USA Today. January 23. http://www.usatoday.com/story/money/business/2014/01/23/fda-to-revise-nutrition-facts-label/4799911/. Accessed Jan. 31, 2014.

NRC and IOM. 2013. U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. National Academies Press, Washington, DC.

OECD. 2013. Obesity and the economics of prevention: fit not fat (U.S. key facts). Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris, France. http://ww.oecd.org/els/health-systems/obesityandtheeconomicsofpreventionfitnotfat-unitedstateskeyfacts.htm. Accessed January 31, 2014.

Preston, S.H. and Stokes, A. 2011. Contribution of obesity to international differences in life expectancy. Am. J. Public Health 101(11): 2137–2143.

Rao, M., Afshin, A., Singh, G., and Mozaffarian, D. 2013. Do healthier foods and diet patterns cost more than less healthy options? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brit. Med. J. Open 3(12). http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/3/12/e004277.full. Accessed Jan. 31, 2014.

Rutten, L.F., Yaroch, A.L., Patrick, H., and Story, M. 2012. Obesity prevention and national food security: a food systems approach. ISRN Public Health, article ID 539764. http://www.hindawi.com/isrn/public.health/2012/539764/. Accessed Jan. 31, 2014.

Saslow, E. 2013. Too much of too little: a diet fueled by food stamps is making South Texans obese but leaving them hungry. The Washington Post, Nov. 9. http://www.washingtonpost.com/sf/national/2013/11/09/toomuch-of-too-little/. Accessed Jan. 31, 2014.

Sassi, F. 2010. Obesity and the Economics of Prevention: Fit not Fat. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Publishing, Paris, France. Seligman, H.K., Laraia, B.A., and Kushel, M.B. 2010. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J. Nutr. 140(2): 304–310.

Sturm, R. 2009. Affordability and obesity: issues in the multifunctionality of agricultural/food systems. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 4(3–4): 454–465.

USDA. 2014. Benefit details: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Alexandria, Va. http://www.benefits.gov/benefits/benefit-details/361. Accessed January 31, 2014.