Unusual Pairings Drive the Next Byte

CULINARY POINT OF VIEW

Chef Laiskonis' Recipe (using IBM's Watson): Ecuadorian-Strawberry-Dessert

After winning Jeopardy three years ago, IBM’s Watson decided to take its supercomputing skills into the kitchen. Teaming up with chefs from the Institute of Culinary Education (ICE), the Watson team launched the Cognitive Cooking project with lofty goal of seeing if a computer can help the most ingenious chefs in the world be even more creative. Drawing on a database of tens of thousands of recipes and ingredient combinations, and input from the chefs, Watson produces a list of ingredients for a dish that the regular foodie has probably never thought of. Florian Pinel, Senior Software Engineer at IBM Watson Group, and Chef Michael Laiskonis, Creative Director at ICE, share their experiences developing and interacting with Watson for the Cognitive Cooking project.

KELLY HENSEL: Where did the idea come from for the Cognitive Cooking project?

FLORIAN PINEL: We started the project about two years ago, right after Watson had just won the Jeopardy challenge. We were wondering what could be next for Watson. What would be a new challenge that would push the boundaries of a company’s computing? And we wanted to see if computers could be creative and help other people be creative. When you look at literature about artificial intelligence, creativity is often considered the pinnacle of human intelligence, so we thought that that would be an exciting goal for Watson.

And from there, we decided to apply creativity to the food domain, because it was relatively easy for us to find recipe information that we could use. Also, we could pretty easily find information about ingredients and a more scientific way to choose food, thanks to information about the flavor components that are found in ingredients for example.

HENSEL: Florian, what’s your role in the project? Have you been involved from the very beginning?

PINEL: Yeah, I was one of the very few people who started the project two years ago. And I’ve been designing the system. I guess you could say I’m the architect of the system.

HENSEL: And for you Chef Michael, when did you and the other chefs from ICE get involved in the project?

MICHAEL LAISKONIS: We were looped in fairly early on. I would say now it’s been about a year and a half. So Florian and his team, which at the time was just two or three people, brought the idea to us to see if we would be interested in partnering up. Obviously, they could benefit because they would have access to our resources and our recipe databases.

I had actually just started in my role here at the school and this was exactly the kind of thing that I was interested in doing. As a pastry chef, I already sort of have that analytical approach to cooking anyway and I’ve always been interested in how can you organize creativity, beyond simply just going into the kitchen and being spontaneous and working by trial and error. So just the very idea of this project from the outset was something that I was very interested in.

HENSEL: Can you guys take me through the process of how chefs work with Watson to generate a final dish?

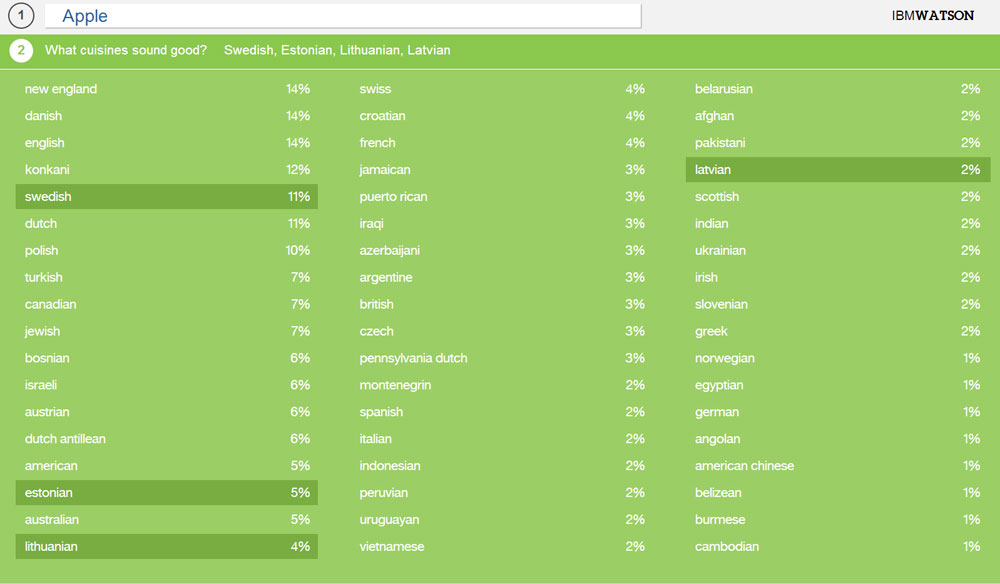

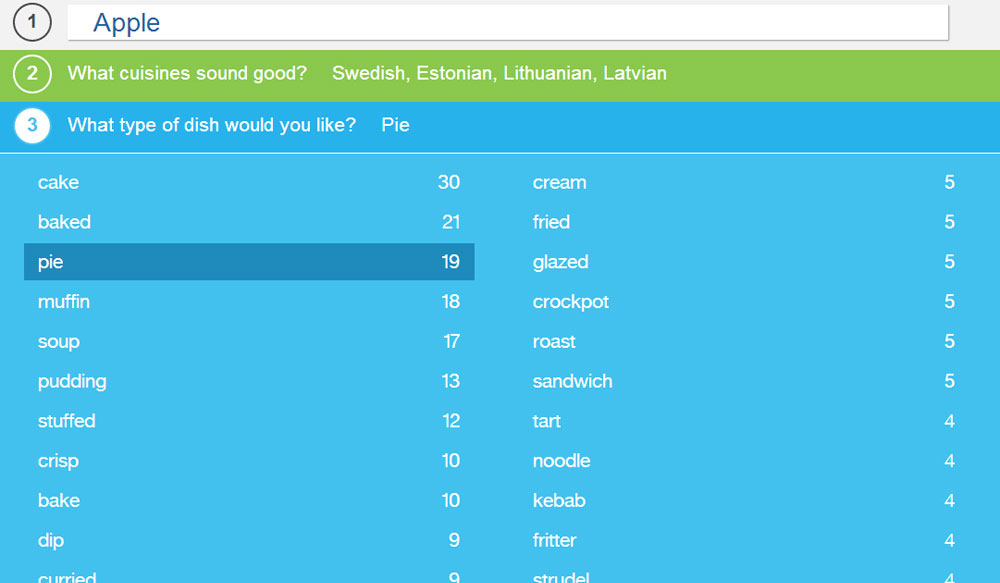

PINEL: So, we first asked people to choose a basic ingredient for a recipe—they can choose anything they want. It can be a vegetable, an herb, protein, whatever, and from there, we tell them what cuisine uses that ingredient the most and what dishes use that ingredient the most and they can choose one or more cuisines and one dish. And those three parameters are really the primary inputs to create a new recipe—the dish, the basic ingredients and one or more cuisines.

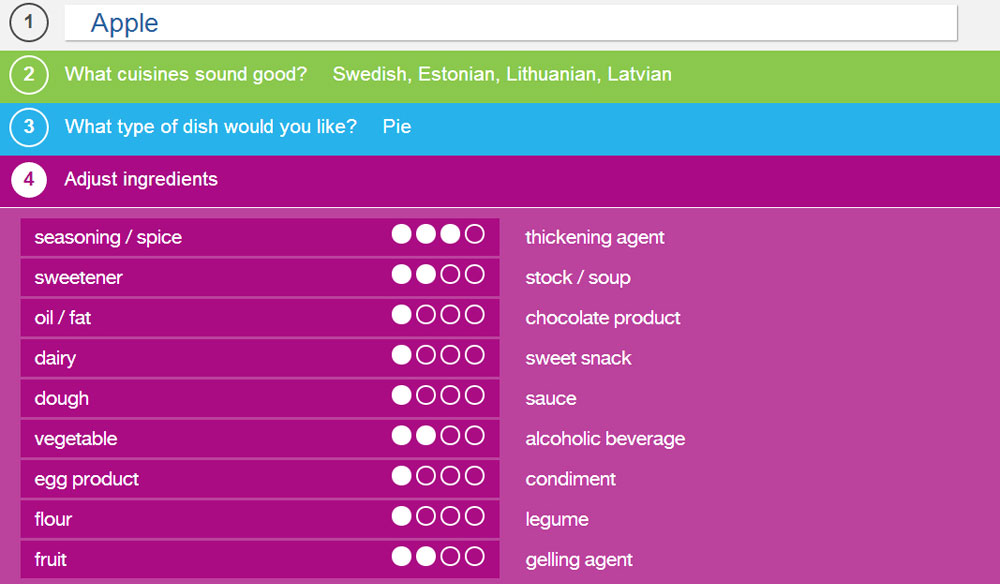

Once we have that, we figure out what other types of ingredients are required to make that particular dish. For example, what makes a quiche a quiche, what makes a pie a pie. What do you need? Do you need one dough, two kinds of vegetables, one egg product, one cheese product, and so on. So we display that and you have a chance again to tweak those ingredient types. You can choose to make something without meat, without seafood, or maybe with vegetables. That’s the last input.

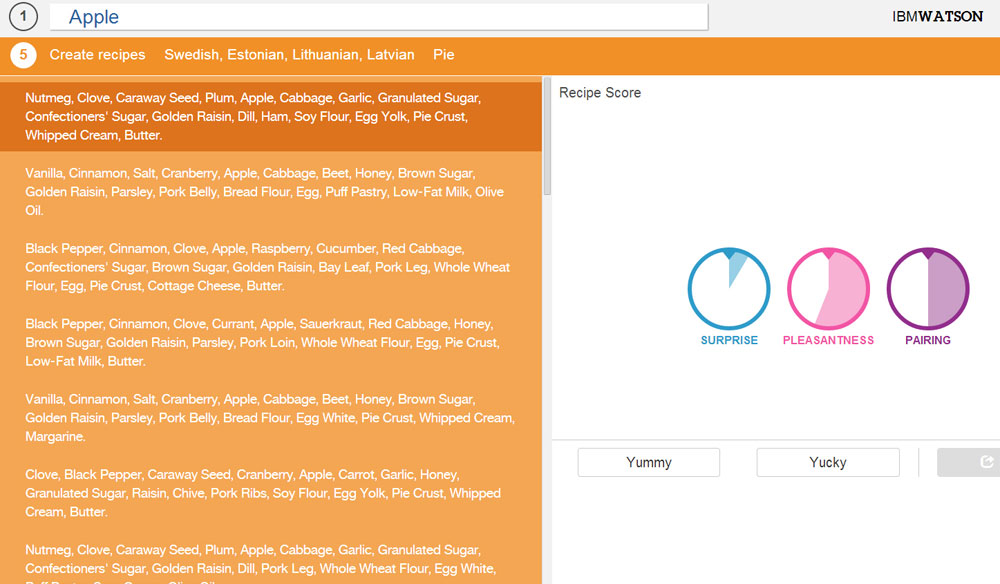

Once you have entered that, the system is ready to create the new recipe. It goes through all the possible combinations of ingredients and there are like billions, trillions, quadrillions of combinations.

LAISKONIS: I would only add to that to say, as we’ve been kind of working on our exercises and obviously the system has been evolving as has our interaction with it has also been evolving, to demonstrate the surprise factor and to kind of come up with things that we haven’t seen before, we’re almost intentionally throwing a curve ball at the system. So for instance, um, you know, using those same three parameters, one of the dishes that we ended up doing in Austin was an Austrian Chocolate Burrito.

So, burrito was the dish that we chose, because we were working out of a food truck, we wanted to celebrate Austin culture, have something portable, something appropriate for lunch. Then, to kind of challenge ourselves and challenge the system, we input Austrian as the cuisine, which is the last thing you think of when you think of a burrito. And then also in terms of an ingredient, I didn’t want to make a dessert burrito necessarily, but I thought it would be interesting to put something in like chocolate, which has so many complex flavors and can easily transition back and forth between sweet and savory just to see what we got in terms of an output.

And within those kind of broader parameters, I could say well, I want something suitable for a wrapper or I could have asked for ingredients that would have given me a place to start with to make my own wrapper. Part of all of our work with it is to actually see how surprising some of the outcomes can be so that we can take it back to the kitchen and actually begin to work on combining those flavors.

HENSEL: Okay. So, just to clarify the system produces a list of ingredients at the end, not a recipe, per say?

LAISKONIS: Correct. It’s all up to the chef and no two chefs are going to necessarily interpret those lists of ingredients the same way, which is the exiting thing.

HENSEL: And is it always a certain number of ingredients?

LAISKONIS: We can totally adjust that. Once again, the more ingredients that we allow for, the more interesting sort of combinations we can get out of it.

PINEL: By the way, about the input for the system, what really matters is at the end we somehow collect one or more ingredients, one or more cuisines, and one dish.

Now, the order in which we do that doesn’t really matter. There’s the form interface where you do pick an ingredient first and then a cuisine and then a dish, but we have another interface where you can just chat with Watson. And through the dialogue, eventually Watson will ask you to pick a dish, ingredients, and cuisines in any order.

HENSEL: In creating a list of ingredients, what attributes does Watson use? Does chemical makeup of ingredients come into play?

PINEL: So it’s first going to see if it should keep an ingredient in the combination, and make sure that the ingredient has been paired often enough with the base ingredient in existing recipes. That’s one. Then it makes sure that the ingredient is found often enough in the cuisine that you selected and it does that by looking at the Wikipedia pages about cuisine among other sources. That’s probably the main two parts in the beginning.

But then there are those three evaluators that are also used to sort the results and the first one is surprise so that’s where you make sure that the combination of ingredients is different from existing recipes. And the second evaluator is pleasantness, which is where we start using the flavor compounds. It’s based on hedonic psychophysics and basically, in the literature you can find experiments where humans have rated the pleasantness of individual flavor compounds. And using that information we try to predict the pleasantness of a whole ingredient and then as a whole combination of ingredients.

The third evaluator is what we call the flavor pairing, which is again based on chemistry. The more flavor compounds the ingredients share, the more likely they are to taste good together in Western cuisine and Eastern cuisine tends to be the contrary.

Screens showing the Watson Cognitive Cooking interface with the selection steps and output:

|

|

|

|

LAISKONIS: What’s interesting with the flavor pairing concepts is that’s usually where surprise comes. I like to say that the system can taste these ingredients virtually and while it is taking into account the frequency that such an ingredient might show up, it’s also tasting them virtually without those biases so it can produce things that you or I might not normally associate together, for whatever cultural basis. Another great example was the pairing of, among other things, strawberry and mushroom, because they shared a common flavor compound. That’s something I would have never have thought to pair on my own and I was skeptical until I got into the kitchen and starting working with these ingredients and playing round with them and found that it actually does work.

And it’s also surprising sometimes what the system doesn’t give you. So for that Austrian chocolate burrito, because it was trying to bring in Alpine or European flavors, what we didn’t get were the usual suspects of a burrito—the heat or spice.

PINEL: Also, I’ve mentioned the three scores—pleasantness, novelty, and pairing—but if you had different benefit, we could have other scores. Imagine you’re a food manufacturing company and you have years or decades of consumer data, it would be very interesting and pretty easy to add that as a fourth score to predict consumer liking.

HENSEL: This technology is exciting for food scientists and technologists. How could this technology be used in R&D for food manufacturers?

LAISKONIS: Well, I certainly think whether it’s on a manufacturing side or even on the consumer side the applications could also extend to dietary restrictions because you can filter out the gluten, sugar, lactose, etc. I can’t speak to how the system would do it in a technical sense, but I imagine Florian that the system can also learn over time and almost become customizable. It will remember your personal choices over time and that will evolve in that direction too.

PINEL: Yeah, definitely, if we had the source of your personal preferences, we could apply that. We’re also kind of ready to apply dietary restrictions. It’s just a matter of someone giving us a list of ingredients that match to each restriction. If we had that, we could just feed it in to Watson today and provide recipes that have those restrictions. I was just thinking that there are databases of recipes available out there that keep like the gluten-free recipes, and if we just looked at all those recipes and built a list of ingredients from them, we would get a pretty good list of gluten-free ingredients right there. It wouldn’t be that hard to get there.

LAISKONIS: But even just from a perspective of just, you know, working with the system enough and browsing the outputs that it gives, I mean it’s going to naturally give us things that we just don’t normally think of. For instance, one of the dishes we did for a small dinner while we were in Austin. It was the Ecuadorian strawberry dessert. And I actually didn’t personally work on the outputs of that. Chef James did. You can tell Watson that you want two different kinds of fat or two different kinds of flour, for example. And one of the fats that it gave to work with was avocado oil. And I’d never in my life worked with avocado oil. So that forced me to do that and now it’s in my arsenal, my battery of cuisine. It forces me to think, if this is a recipe that I would normally use butter for, how can I substitute the avocado oil. So working with the system has already changed the way I approach creativity and approach ingredients. And that’s after just working with it for a year to a year and a half.

HENSEL: So, it seems like it would be an interesting addition to a chef’s kitchen. Do you feel that way Chef Laiskonis?

LAISKONIS: Absolutely. And it was actually in our very first meeting that I had with Florian when he was sort of laying out his vision for the cognitive cooking project. I ran back to my office and grabbed something that I had done sort of on an analog level, which was just to create a flowchart of every possible way I could manipulate an ingredient. I had done this several years ago. I could probably update it now, but it was something I could always reference if I ever got stuck. Because I feel as a chef, the more I know, the harder it is. It means I just have more choices I can apply. Or sometimes, you know, there’re things I might be overlooking. For example, if I have an apple and I’m thinking to myself well, I don’t want to make a tart, and I don’t want to make a sorbet. And if I am just stuck, this flowchart that I made was something that I could refer to. Like what would happen if I dipped it in liquid nitrogen or what if I dehydrated it or what if I gelled it or fermented it. It reminded me of a lot of different options.

I’ve thought about this for years now it seems, and I’m sure in hindsight, a lot of the ideas weren’t that great, but when I was a younger cook or a younger chef, it seemed like the ideas just flowed. And that’s because my skillset was limited. It was easier to come up with things. I mean now that I have so many options and hopefully a little bit more maturity and refinement, for me now it’s what I don’t use or what I don’t apply to an ingredient. So, it’s interesting that working on this project is coming at the point in my career that it is, because it is actually very liberating.

PINEL: We have also started talking to food manufacturers, to flavor houses and to companies that create fragrances. We had several meetings with some of them.

HENSEL: Florian, you’re not a typical software engineer. You have a culinary arts diploma from ICE. Could you explain how these two complement each other in your work?

PINEL: The culinary arts diploma is something I pursued while I was already working for IBM and I was just spending a lot of time cooking on my own and I wanted to get better at it and learn how to do it as best as I could. So, that’s why I joined the ICE program for culinary arts and I was doing that on weekends for about six months. And then I did an externship in a restaurant in New York and I actually kept working there after the internship for a few years.

Even I finished the diploma at ICE and the internship, I didn’t imagine that the two interests would meet. And it was only two years ago that somebody else in our team had that idea of using Watson to promote creativity in the area of food, and I was like “This is a perfect match for me.”

HENSEL: Chef Michael, you’ve worked at the renowned Le Bernardin as the Executive Pastry Chef and now are an established teacher at ICE. Did you ever imagine partnering with a technology titan like IBM?

LAISKONIS: It’s interesting because over the span of the first 15 years of my career, which I’m now about 20 years into, I’d always had very solid goals. And one of those was to get to New York and to work in a Michelin three-star restaurant. I had that one from very, very early on, and I achieved that goal, quite luckily. After I’d been at the restaurant for six or seven years, I started to realize I was so busy that I hadn’t set a new goal.

And I could have certainly stayed on at Le Bernardin. To some extent, it was most important job had. I kind of took the approach of well, you know, in this day and age, there are a lot more opportunities and platforms available for chefs—and pastry chefs in particular—so, I kind of thought to myself well, if it’s not broken, let’s break it and see what happens. So my leaving the restaurant was even announced I had already begun talking to Rick Smilow, the President of the school [Institute of Culinary Education], and we started brainstorming about what I could do for the school. So we made up a title of Creative Director, and my role now and a lot of the things I do are behind the scenes.

But I’m also interacting with the career students giving guest lectures. I’m also teaching some of my own classes. The focus is on professional development and then just being, as much as I can be, an ambassador for the school and also to work on special projects like this. So the fact that this opportunity with IBM came along soon after I started at ICE was perfect timing. I’ve always been interested in the mechanics of creativity. Even before I started cooking, I was pursuing a fine arts degree so it’s something I’ve thought about it and tried to think of how to apply the vocabulary or the mechanisms of other media to cooking and it becomes kind of a big philosophical question. How do you organize creativity? The flowchart I mentioned before was very much inspired by the things that Ferran Adriá from elBulli in Spain had done just to help a chef think in a more organized way.

The reason I decided to take a leap and to leave the comfort of the restaurant world is precisely to work on this kind of project.

HENSEL: You guys have already mentioned the Austrian chocolate burrito, which one of the dishes the food truck presented while at SXSW Interactive in Austin, Texas, in March. Was there another combination of ingredients during that show that was interesting to you guys?

PINEL: I’ve been mentioning the bacon pudding several times. You had the bacon and the custard. That was combined with the raisins—

LAISKONIS: —walnuts, dried fig, orange peel, oh and cumin. As the spice that kind of threw me and made me realize that in all my years, I’ve never used cumin in a sweet context. Oh and the addition of the mushroom. I’ve played around a little bit with mushroom-based desserts, I mean literally two or three times in 20 years and this forced me to jump in and try it. That interplay between the smokiness of the bacon and then that sort of hard to explain umami character of the mushroom. It really worked.

HENSEL: So, would that be the most interesting combination for you too Chef Michael?

LAISKONIS: For me, I would go with the Vietnamese apple kabob. The fact that Watson gave us five ingredients that shared that D dodecalactone compound were chicken, pork, mushroom, pineapple, and strawberry. So, if you take almost any two of those—like the strawberry and pineapple—you would get it, or the pineapple and the pork makes sense. The chicken and mushroom pairing makes sense of course. But all together it was extremely surprising. That was also one of the very earliest recipes that I personally worked on. It forced me to think about everything I associate with a kabob and in this case I decided well, why does a kabob need a stick? I started researching what’s normally in a kabob-like item from Southeast Asia and often it’s usually some sort of ground meat instead of just chunks skewered. So I learned a little bit about Vietnamese cooking. I also had to make a lot of different choices as to how I was gonna express each ingredient. Those choices were left up to me. I decided what proportions each ingredient played in the final dish and I could have easily hidden the strawberry. But I wanted to make sure it was front and center. So not only did I learn some things just in the process of coming up with a dish, but it also opened my eyes to different possibilities.

Another good example of that was with the burrito. The flavor profiles were unexpected, so I wanted to make sure we delivered that in a very familiar format. It looked like a burrito. But one of the dishes that James worked on was fish and chips and he rethought the whole idea of why the fish has to be fried, so he ended up doing a ceviche. He did a corn and coconut fritter if I recall, and then the chips were in the form of fried plantains. So again, that was his personal journey of working with those ingredients.

HENSEL: What does the future hold for the Cognitive Cooking project?

LAISKONIS: He [Pinel] can probably speak better to what actually may happen with it and I can maybe say what I’d like to see happen with it. I would absolutely use this probably on a daily basis. It would actually also probably be my primary form of entertainment. I wouldn’t need television if I could just browse through it for hours on end. I also think it would certainly work on a professional chef level. Obviously, it could be extended to any creative endeavor, food or otherwise.

I also think it’s really interesting and I think we saw this on the ground in Austin, looking how just the general public and the general consumer interacted with it. I think it would be really interesting to see an application where, for instance, you could plug in the ingredients that are currently in your refrigerator and, in this case, a consumer application might offer a little bit more in terms of a recipe guideline. Because the average consumer might not have the scope of cooking knowledge that a professional chef has. Or perhaps, you’re in market and the tomatoes look great and the asparagus looks great. As you’re wondering the aisles, the app could help you figure out what else you need to buy in order to make a great meal. That’s from my very non-technical perspective. That’s how I would love to see this evolve.

PINEL: And what do you think Florian? What do you see happening in the future?

PINEL: There are two possible accesses I can think of. One is about the food manufacturing companies for example using the system to create new product. Or companies that are now doing something outside of the food domain, such as the fragrance industry or the fashion industry, could also be interested. There could be applications in business process management because a business process looks very much like a recipe. So, you could imagine creating new business processes for business analysts. Or other areas of manufacturing, as long as you’re trying to make a product that’s made of small components.

The other access is more oriented towards the general public and that’s actually what we’re looking into in the Watson Life Group I belong to now. We’re trying to see what people expect from company’s computing and how can we help them in their daily lives and help them be more creative. We don’t have an answer yet, but we’re talking to many people. We’ve been talking to consumers at SXSW, we’re talking to supermarkets, we’re talking to the food media, all about what we could do potentially.

LAISKONIS: I think a great example of the possibility as it was explained to me is that the generation of Watson that was on Jeopardy, the end goal was not simply to put a computer on a game show. That technology is actually now being used in cancer research. To me, that’s really inspiring.

Ecuadorian-Strawberry-Dessert

By Chef Michael Laiskonis

Watson system output: Strawberry, peach, papaya, coriander, cumin, confectioner’s sugar, yogurt, heavy cream, dried apple, pectin, coconut, egg yolk, avocado oil, flour

The inspiration for this dessert relies on both the fresh fruit flavors provided, but also by channeling some of the dessert traditions of Latin America while tying the elements together with contemporary and classic pastry techniques.

Initial Latin American influences included churros and dulce de leche. Churros are typically made with a batter similar to a classic pâte à choux; this batter would have to be dramatically reformulated to account for the limitations of ingredients: using the cream and avocado oil, I was able to approximate the fat and water content of a conventional recipe. And rather than fry the batter as churro, I opted to bake the batter in order to lighten the dish and allow for more interesting textures, in part provided by the crunchy sablée topping. The novel addition of the avocado oil lends an interesting flavor to the finished piece.

The ‘dulce de crema’ was achieved simply by reducing heavy cream to promote the Maillard reactions that give this preparation its distinct flavor, lightly sweetened with confectioner’s sugar. And the coconut cream used to fill the choux resembles Puerto Rican ‘tembleque.’

The various fruit elements were treated to showcase different textures and temperatures: sodium alginate was employed to produce liquid-centered strawberry spheres, pectin to thicken a peach coulis, and yogurt was combined with peach to offer a creamy yet light peach sorbet. Flavorful strawberry water was produced to hydrate the dried apples which form a salad along with the papaya.

The two biggest challenges were dealing with the absence of butter and the selected spices. Because I had the ability to use cream, I simply made my own butter for those components that benefited from it. To incorporate the spice, I decided to apply those bold flavors into a neutral caramel, providing another textural contrast but with very little added sweetness.

Yield: approximately 6 portions

Butter

2 liters heavy cream (40% fat)

- Whip the cream on medium speed for approximately 20–25 min until the fat separates from the liquid.

- Drain the butter solids, (reserving the buttermilk) and wash the butter in ice water.

- Place the butter on a cold surface and knead to remove excess moisture. Reserve.

‘Dulce de Crema’

250 g heavy cream (35% fat)

Confectioner’s sugar, to taste

- Slowly reduce the cream, stirring occasionally, until most of the water has evaporated and the cream takes on a light brown color and thickened consistency.

- Remove from heat and add confectioner’s sugar to taste. Reserve.

Choux Sablée

52 g reserved butter

65 g confectioner’s sugar

65 g all-purpose flour

1 g salt

- Place all ingredients in the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with paddle; mix on low speed just until combined, adding a small amount of water if necessary.

- Roll the dough between two sheets of acetate cut to approximately 15 cm by 20 cm. Freeze.

- Cut the sablée dough into 3 cm discs.

Avocado Oil Choux

200 g heavy cream (35% fat)

60 g water

20 g avocado oil

10 g confectioner’s sugar

2 g salt

75 g all-purpose flour

75 g high gluten flour

140 g egg yolks

- Place the cream, water, avocado oil, confectioner’s sugar, and salt in a saucepan and bring to a rolling boil.

- Remove from heat and stir in the flours until combined; return to heat and cook for 1–2 min until a smooth mass has formed.

- Transfer to the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with the paddle attachment. Beat the mixture until slightly cooled; incorporate the egg yolks in the small amounts.

- Transfer the paste to a pastry bag and deposit into 2.5 cm silicon hemisphere forms. Freeze.

- Unmold and top each frozen choux with a 3 cm disc of the choux sablée. Gently warm the surface with a heat gun, allowing the sablée to evenly drape the choux. Temper to room temperature.

- Place in a 340°F/170°C oven, and bake for 5 min. Reduce the heat to 320°F/160°C and continue to bake an additional 5 min. Reduce heat to 300°F/150°C and finish baking until golden and dry, approximately 10 min.

Coconut Pastry Cream

250 g coconut purée

250 g heavy cream

100 g confectioner’s sugar

20 g all-purpose flour

80 g egg yolks

1 sheet gelatin, bloomed

20 g reserved butter, softened

- Place coconut purée and cream in a heavy saucepan and bring to a boil.

- Meanwhile, sift together confectioner’s sugar and flour. Reserve.

- In three additions, whisk dry ingredients into the egg yolks. Temper the hot coconut mixture into eggs and return to medium heat.

- Stirring constantly, continue cooking until mixture is thickened and returns to a boil.

- Remove from heat and add the gelatin. Transfer the mixture to a stand mixer bowl fitted with the paddle attachment. Beat until cool and add the softened butter.

- Pour into a shallow container, cover with plastic wrap and chill.

Strawberry Water

250 g strawberries, cleaned and roughly chopped

50 g sucrose

- Combine strawberries and sucrose in a large bowl. Coarsely pulse with immersion blender. Cover and place in warm area and allow to stand 6 hrs.

- Transfer to refrigeration and allow to chill, at least 4 hrs, or overnight. Strain the mixture, discarding the solids.

Strawberry Sphere

200 g strawberry purée

5 g calcium lactate

0.5 g xanthan gum

- Shear the ingredients together with an immersion blender for at least 2 min. Deposit into small hemisphere forms and freeze.

1000 g water

7 g sodium alginate

1 g sodium citrate

500 g syrup (60% water/40% sucrose)

Shear the water, sodium alginate, and sodium citrate together with an immersion blender for at least 2 min and allow to fully hydrate for 2 hrs. Drop the frozen strawberry forms into the alginate bath and allow to set for 3–4 min. Gently transfer to a clean water bath, and then into the syrup for holding.

Peach-Yogurt Sorbet

30 g sucrose

2 g ice cream stabilizer

75 g water

100 g sucrose

5 g glucose powder

5 g invert sugar

480 g peach purée

320 g plain whole milk yogurt

- Combine first measurement of sugar and stabilizer.

- Heat water to 120°F/50°C. Whisk in stabilizer, then remaining sucrose, glucose, and invert sugar. Bring to a boil for about 30 sec. Remove from heat.

- Chill and allow syrup to mature for at least 4 hrs.

- Combine syrup, peach purée, and yogurt. Process in batch freezer.

Peach Coulis

125 g peach purée

25 g confectioner’s sugar

2.5 g pectin

- Place the peach purée into a small sauce pan and bring to a gentle boil.

- Combine confectioner’s sugar and pectin and whisk into the purée. Resume a boil, remove from heat, and allow to cool.

Cumin-Coriander Caramel

100 g fondant

100 g glucose

100 g isomalt

cumin, finely ground

coriander, finely ground

salt, as needed

- Combine fondant and glucose in a saucepan and begin to cook. Once dissolved, add isomalt. Cook to 325°F/163°C.

- Pour sugar onto Silpat and allow to cool completely. Transfer to a coffee grinder and process to a fine powdery consistency.

- Sift over a desired stencil onto a Silpat, sift the spices and salt, if desired, over the caramel base. Remove stencil and gently cover with a second Silpat. Place in a 300°F/150°C oven for 90 sec. Remove from oven and allow to cool.

- Store in an airtight container.

Assembly

- Fill each choux with the coconut pastry cream and dust with confectioner’s sugar.

- Arrange two to three choux puffs on each plate and artfully garnish with the remaining components. Serve immediately.