Chef David Lebovitz: Living ‘la Bonne Vie’ in Paris

CULINARY POINT OF VIEW

Photo ©Ed Anderson

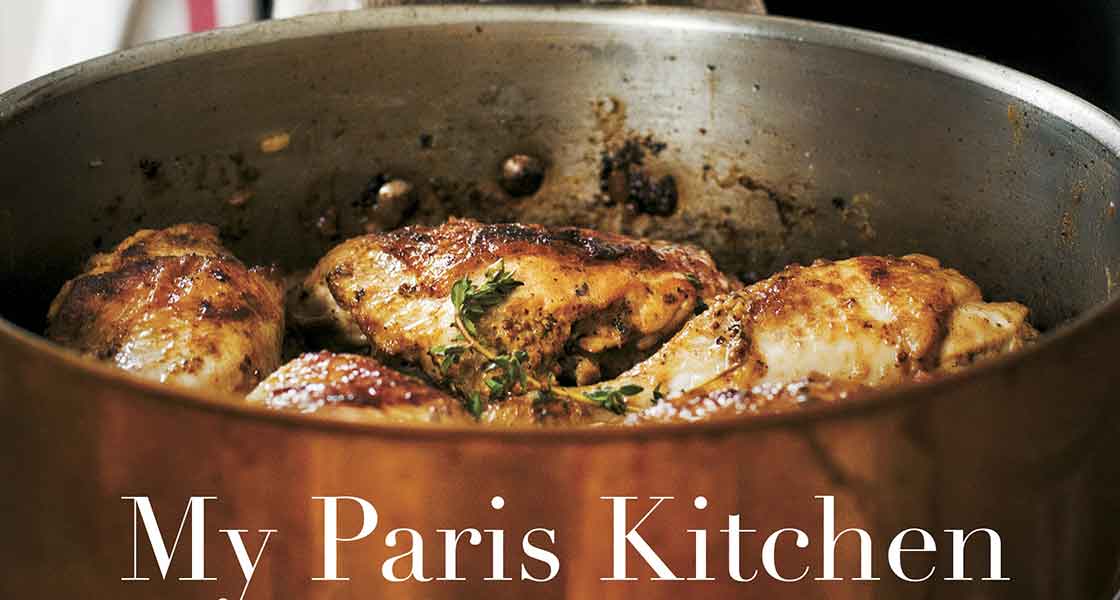

David Lebovitz's Counterfeit Duck Confit recipe

It’s been more than a decade since David Lebovitz, former Chez Panisse Pastry Chef, left the United States to explore the cuisine and culture of Paris. During that time he started his eponymous and popular blog, acclaimed both for its humorous depictions of expat life in Paris and its recipes, and has written seven cookbooks. Now considered one of the leading voices on French cooking, dining, and living, Lebovitz shares his views on Paris cuisine and the business of blogging.

Kelly Hensel: You got your start working with the renowned Alice Waters. Is there a piece of advice or learning from her that you still carry with you to this day?

David Lebovitz: Yes—to keep it simple. Everyone’s thinks: “What can we do to make this better or different?” Making it better is one thing, but adding another sauce or a scribble of something unnecessary to the plate isn’t actually making anything taste better. Usually, it’s just complicating things. There’s nothing wrong with a really good iceberg lettuce salad with blue cheese dressing; you don’t need to add ham or grilled shrimp to it.

Hensel: You’ve been living in Paris for 11 years. How have you seen the food scene change during that time?

Lebovitz: Parisians have become much more aware of what they’re in danger of losing. Like many countries and cultures, the French have also embraced fast food and supermarket shopping because they are busy and shopping for convenience. But, I’ve seen people return to thinking about eating locally and considering where their food is from.

I would say 80% of the time at a Paris market, you aren’t buying produce from the farmer directly—they are just middlemen. But, what I’m seeing is that the vendors who are the actual producers and farmers have the longest lines. Even though it’s often more expensive, I think people are starting to shop for taste again.

Photo ©Ed Anderson

Hensel: You mentioned fast food just now and you wrote a lot about globalization in your book. Are there any positive aspects of globalization impacting Parisian cuisine?

Lebovitz: French people will say: “Why would you leave France for vacation? We have everything here.” It’s actually true—France has a tropical climate, mountains, the Alps. France has everything. So a lot of people didn’t travel but now they are and they’re saying, “Oh, there’s actually good food in America.” They are realizing that Mexican food isn’t just cans of Old El Paso, which is what you see at the supermarket. The French people are much more open-minded now.

Hensel: I recently interviewed Chef Einat Admony and she said that she believes the best bread in the world is made in Germany. I wanted to get your reaction to that. Does Paris have the best bread?

Lebovitz: I just bought a really good baguette and I actually ate German bread today. I also just picked up tortillas from the local Mexican place that makes tortillas near me. All three are great, and I don’t think I can say what’s best. There are bad baguettes, there are good baguettes, there’s great sourdough bread in America, and there’s bad sourdough bread in other countries.

She’s probably likes the hearty German bread, which I also like. I’ve been to Germany a few times and it’s actually hard to get a lot of those breads. They don’t have the bakery culture that they do in France. A lot of times I would buy bread that looked dark and delicious, but when I cut it open it was a big airy sponge. It happens in France, too.

There really good bread in France. There’s good bread in Israel, too. You just have to find the people that are doing it right, wherever you’re going.

Hensel: What are the biggest differences between France and American food culture?

Lebovitz: Well it’s hard to classify America because it’s such a huge, diverse country. I think I would say ingredients are a lot more readily available in France. There are five bakeries two blocks from my apartment and there’s a couple fromageries that have very good cheese. There’s also a lot of compartmentalization when you shop in France. You go to one person to buy cheese, another person to buy meat, and another person to buy herbs.

I do think that America has more diverse produce. Every American that moves to Paris will say, “Where is the kale?” The French just don’t eat kale. They don’t eat bitter things. The French palate is much more about zucchini and eggplants—you can see those all year around. But in America you go to the supermarket and there’s like 14 kinds of onions and all these lettuces. In France it’s a smaller, more edited selection of things.

Photo ©Ed Anderson

Hensel: You’ve written eight cookbooks. What have you learned about writing a successful cookbook that you didn’t know at the beginning?

Lebovitz: I would say the most important thing is to put your voice in the book. There are so many cookbooks out there. People have said to me, “Every time I read your book, I feel like you’re talking to me,” That’s just how I write. I am not a trained writer so I just write like I talk. I also have a blog where I tend to be a little more casual than in my books. The book is a little more of a reference material.

My new book—My Paris Kitchen—actually wasn’t supposed to be a cookbook. But my publisher said, “You know, this needs to be a cookbook.” I don’t mind giving recipes, but people have gotten so peculiar about cooking and recipes. I want people to be more relaxed and realize that you don’t have to stress out over making a dish. And so I tried to be more casual with this book, but at the same time still have recipes that were very doable.

Hensel: What I loved about your latest book is that it doesn’t just contain French recipes. You include recipes for Middle Eastern food, Indian food, and North African food. Is the eclectic mix representative of a changing—more diverse—food culture?

Lebovitz: There’s a huge North African population in Paris. Somebody wrote to me and said they were going to buy my book but they found it very strange to have a book about Paris cuisine with recipes that weren’t French. I wanted to respond, “Well, what’s French?” Foie gras is Egyptian. Is that French? Italians didn’t always have tomatoes. French food is evolving.

Hensel: Has the food culture become more diverse in Paris or has it always been that way?

Photo ©Ed Anderson

Lebovitz: Well, there were always a lot of ethnic restaurants, but the quality wasn’t so great. Part of that is because they don’t have a large middle class of ethnic people. In America, there are a lot of Asians in different socioeconomic classes and they want to eat out. Also, there’s an appreciation by non-Asian people for good Asian cooking in America. The French don’t have that—they’re not looking for superb sushi; it’s not part of their DNA. You can get good ethnic food in Paris, but you have to know where to go, and it’s not as widely available as in America.

Hensel: Are the recipes that you included in the book some of your favorites? How did you make that decision on what to include?

Lebovitz: I always want to do recipes people can—and will—make. There’s no use putting in a recipe for like goat stew when no one would be able to get goat. I really try to make sure most of the ingredients are available. Duck legs—not everybody can get those, but those are really French, and they aren’t that hard to find. Also, I don’t like to spend all day cooking. I’d rather throw something in the oven, like some ribs, and let them braise for six hours. That’s how I cook and the book is a reflection of that.

Hensel: How long does it take you to develop a cookbook from start to finish?

Lebovitz: Well, usually you have a year to write a book. I find that I can’t do anything else while I’m writing a cookbook, I just obsessed with it. I think of each of my books as a kind of a story about my life, a certain place in time, a certain thing I’m developing. It’s very personal.

Photo ©Ed Anderson

Hensel: Your book has the same feel as your blog with lots of honest and humorous stories about living in Paris. You don’t idealize the city. What kind of feedback do you get?

Lebovitz: So, I don’t think people are perfect anywhere. I actually like flaws. I think it’s funny and interesting, and what makes us different. There’s a whole politically correct movement in America, and French people are like “So why are people in America so politically correct?” In a lot of ways we tend to want to erase our differences. And our differences are what make us funny, interesting, and human.

Hensel: You were blogging before it was even called blogging. Now it seems everyone and their mother blogs about food. As a chef and blogger what do you think about this?

Lebovitz: I think it’s good. You know, when I started, I was just writing—it was a website. And then, around 2003 or 2004, I started seeing these other people writing about food, and there was software that allowed even those without any tech skills to have a website. It started to be known as blogging. It was only like seven people for a year, and we all kind of knew each other. We would say, “Have you checked out this? There’s someone in Korea writing about noodles.” But then it got so big so quickly, you couldn’t keep track of all the new blogs.

Blogging is great—it’s very democratic. In the old days, if you wanted to be a food writer, you had to approach editors. Now, anybody can do it. We have a really strong food blogging community and people really look out for each other. There’s really good blogs out there, and I feel bad because a lot of them just don’t get traffic because there’s just so many blogs.

Hensel: How long does it take you to finish a blog post, from writing to posting online?

Lebovitz: It probably takes three days. For example, I just made some bread today and took some pictures. I started writing notes down so that I could sit down at a later time and write the recipe and a story, edit the photos, and upload them, and so forth. So, the whole process probably takes at least 10–20 hours.

Blogs used to be more of a journal and didn’t need to be a showcase for your talent. But people expect better photos now and they point out your grammatical mistakes. And while I like doing photography and learning about how to compose nice photos, I also miss being able to go out to lunch, come home, write, and immediately publish a piece. That’s what the blog is supposed to be. It’s not just supposed to be pretty pictures of a cake I made and the recipe. It’s about Paris. I might start losing readers, but I am trying to return to that—be a little more genuine.

Hensel: As a pastry chef, I imagine that there isn’t a better place to live than Paris. Who serves your favorite pastry in a city of over 1,300 bakeries?

Lebovitz: Well, today I had chouquettes [see David's recipe for chouquettes], which are cream puffs with pearl sugar on them. And that’s actually one of my favorite things because it’s so Parisian. You get a little bag of them and you eat them on the street as you walk. And they’re not heavy—you’re not sitting there eating this big piece of cake, so you don’t feel bad when you’re done with them.

Photo ©Ed Anderson

Counterfeit Duck Confit

Excerpted from My Paris Kitchen by David Lebovitz (Ten Speed Press). © 2014. Photographs by Ed Anderson.

Serves 4

The first time I tasted duck confit, I declared it the best thing in the world, a belief I stuck to for the next 25 years. And unless something better comes along, I’ll stick to it for the next 25 years as well. The shattering skin, fried to a crisp in velvety duck fat and encasing tender meat that easily pulls away from the bone, is in a class by itself. Fortunately, in France, it’s very easy to buy already made duck confit (which means “pre-served”) at any butcher—and even in the supermarket. To be honest, it’s exactly like what you make at home, and considering how many quarts of duck fat you need to make a batch, it’s easier to pick up a few preserved thighs, and fry them up whenever the mood strikes.

I’ve had a lot of duck confit in my life, and this counterfeit version tastes every bit as good, with a lot less fuss and no mess. Because it’s not preserved for a long time, it’s not a true confit, but the trade-off is that I can eat it just a few hours after I’ve started it. I’ve adapted techniques from food writers Regina Schrambling in the New York Times and Hank Shaw on Simplyrecipes.com to come up with a new-fangled way of making this traditional dish possible with practically zero effort.

The trick to this ridiculously easy technique is to use a dish that will hold the duck thighs snugly pressed together, which allows them to “confit” as they bake. If you only have a larger dish, increase the recipe and cook extra duck legs. Traditionally, duck confit is served with Potatoes cooked in duck fat and a green salad. But since we’re already bucking tradition, you can also use the shredded duck meat in place of the bacon in a salade lyonnaise. And, of course, it's obligatory in cassoulet.

4 duck thighs (thigh and leg attached)

1 tablespoon sea salt or kosher salt

1 tablespoon gin

1/4 teaspoon ground nutmeg 1/4 teaspoon ground allspice

2 cloves garlic, peeled and halved lengthwise

2 bay leaves

- Prick the duck all over with a needle, making sure to pierce all the way though the skin.

- Mix the salt, gin, nutmeg, and allspice in baking dish that will fit the duck legs snugly, with no room around them. Rub the salt and spices very well all over the duck

- Put the garlic and bay leaves on the bottom of the baking dish and lay the duck legs, flesh side down, on top of them, making sure the garlic cloves are completely buried beneath. Cover with plastic wrap and refrigerate for at least 8 hours, or overnight.

- To cook the duck, wipe the duck gently with a paper towel to remove excess salt, then put the duck back in the dish, skin side up. Put it in a cold oven. Turn the oven on to 300ºF (150ºC). Bake the duck thighs for 2.5 hours, taking them out during baking once or twice and basting them with any duck fat pooling around them.

- To finish the duck, increase the oven temperature up to 375ºF (190ºC) and bake for 15 to 20 minutes, until the skin is deeply browned and very crispy