Meeting Industry’s Science and Technology Needs

What exactly is it that the food and drinks industry needs from innovation in science and technology? By consulting its worldwide membership, a UK science and technology organization has received some answers.

Food and drink production, preservation, distribution, and supply rely heavily on science and technology, which facilitate so much of the innovation that we see in the food and drink marketplace. As a major provider of research and wider scientific and technical services to the sector, we at Campden BRI seek to understand exactly what it is that industry needs from science and technology. So every three years we consult our members (Sidebar 1, “The Consultation Exercise”), pool the findings, and publish the results (Campden BRI 2015 and Sidebar 2, “Major Needs Identified in the Consultation”). By sharing the findings as widely as possible, we aim to encourage other providers to meet industry’s needs and, indeed, encourage funding bodies to tackle the precompetitive problems that the industry has highlighted as most significant. This article outlines some of the findings from our latest consultation and how they will be put to use. Figure 1 depicts the way in which the needs have been organized and classified—both by driver (Sidebar 3, “What Is Driving Industry Needs”) and stage in the supply chain—which helps in addressing them.

Product Safety

Delivering products that are safe through their shelf life is seen as the first imperative for food and drinks companies. Not surprisingly then, the means for assuring the safety of the end product and troubleshooting product safety problems, should they arise, was a major driver for industry needs.

The needs themselves focused on minimizing contamination during primary production; managing hazards and risks in processing, distribution, and sale; and protecting the consumer through appropriate guidance.

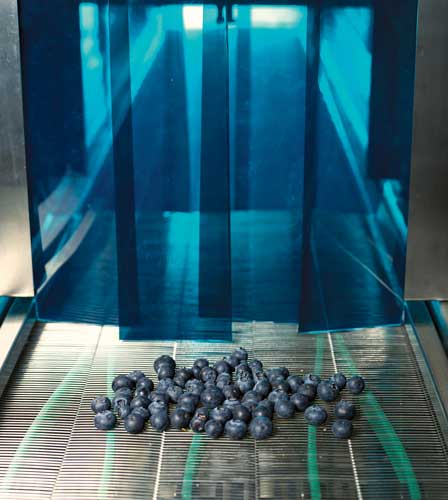

Perhaps a good example of this, in practical terms, is the problem surrounding the management and control of foodborne viruses, such as norovirus, Hepatitis A, and Hepatitis E. On the one hand, there is the need for continued work to improve our understanding and prevention of the sources of contamination as well as implementation of good hygienic practice. But there is also a need to understand the relative efficacy of control measures such as washing, dry decontamination, or thermal processing, so that appropriate control measures can be introduced. This will require investigations in a range of areas including agronomy, processing technology, and methods of detection that generate meaningful results (e.g., that reflect “infective dose,” if at all possible). There are also many “established hazards,” such as mycotoxins, heavy metals, and acrylamide, for which improvements in measurement and/or control are sought.

In a survey by the UK Food Standards Agency, the government agency responsible for tackling food poisoning, an incredible 83% of respondents admitted to one or more behaviours when cooking at home that could put them at risk of food poisoning (FSA 2013). Not surprisingly then, in our consultation, there was also considerable discussion about how to provide consumers with clear, simple, evidence-based guidance on preventing poisoning caused by poor handling, storage, and cooking.

Underlying these practical considerations are some more philosophical issues, such as what constitutes a significant level for hazards where that is not already known. For hazards such as allergens and emerging pathogens, there is no quick or simple answer.

Product Quality and Value

Quality is in the eye of the beholder. The needs articulated by industry are recognition that the most crucial aspect of this is delivering quality that at least meets—but preferably exceeds—consumer expectation. That having been said, there was also a lot of discussion around how quality can best be defined and specified, not just in terms of the sensory experience, but also physical, chemical, nutritional, and microbiological attributes and their measurement.

Compared to the previous consultation three years ago, the recent exercise saw a new aspect to quality as a driver of needs, namely value. In the United Kingdom, the food retail arena is dominated by a few big players, with four—Tesco, Morrison’s, Asda, and Sainsbury’s—accounting for about two-thirds of the market share (Anonymous 2015a). However, these are being challenged by emerging discount retailers such as Aldi and Lidl, which are looking to compete on price and value (Gibbons 2014). Innovation—with science and technology at its heart—is likely to be a significant aspect of achieving the best possible value without compromising on product quality.

Consumer Health and Well-Being

There is considerable pressure from government, lobbying groups, consumer groups, and consumers themselves to reduce the levels of salt, saturated fat, and sugar in foods. This is reflected in a number of needs. Perhaps most obviously, the principal need articulated was to achieve this through product reformulation, finding ways to reduce or replace these components without adversely affecting quality. The solutions might extend as far back in the supply chain as developing new crop varieties delivering ingredients with new or modified properties although there was also significant interest in the use of processing and packaging technology to retain nutritional value throughout shelf life.

Likewise, there is a need to better understand the science underlying the development of products for consumers with special dietary needs—for example in relation to diabetes, cardiovascular disease, age, or food intolerances (free-from foods).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

These needs were complemented by significant interest in helping the consumer to make healthy choices. Whether the solution to this need is more social and political than technical, it is likely that science and technology have significant roles to play in supporting health claims (as part of product marketing), provision of guidance to consumers, and understanding the basis of purchasing decisions.

Supply Chain Resilience

Supply Chain Resilience

Resilience of the supply chain arose in the discussion from two perspectives. On the one hand, there was concern about securing the food supply long term. For example, how might climate change affect the performance of crops in those areas where they are currently cultivated? And what might be needed—in terms of crop development and agronomic practice—to ensure the continued production of the raw materials and ingredients needed? In a similar vein, there were more immediate concerns expressed about the protection of crops. Within Europe there has been a significant shift toward integrated pest management and the withdrawal of a number of active ingredients in pesticides (Stanley 2014). The need arising from this is for a better understanding of pests and diseases threatening crops and effective ways for their control.

The second aspect of resilience relates to protecting the supply chain (and hence the consumer) against fraudulent or malicious activities. In January 2013 the Food Safety Authority of Ireland published a report of the presence of horse and pig meat in products labeled as beef. This precipitated a chain of events culminating in the United Kingdom in the creation of a Food Crime Unit within the UK Food Standards Agency (FSA 2014; Pendrous 2014), but there is also a lasting impact in terms of heightened awareness of the threat of food fraud. Another practical manifestation of this and earlier incidents, such as melamine adulteration of milk products and animal feed from China in 2008, is the development of Threat Assessment and Critical Control Point (TACCP) for anticipating and managing threats to supply chain integrity (Leathers 2014). Clearly, in instances such as melamine, issues of adulteration and authenticity have implications not just for product quality but also consumer health.

Environmental Sustainability

Efficient use of energy and materials with minimal environmental impact had emerged quite strongly in the 2009 and 2012 consultations Campden BRI conducted, and although these topics were present this time around, they were generally not voiced quite as strongly, giving way in part to the heightened awareness of food fraud, supply chain integrity, and nutrition, health, and well-being.

That having been said, there was continued interest in producing more with less and managing resources to minimize waste, both through production (e.g., energy consumption) and in the end product (consumer disposal of product and packaging). One particularly difficult area is reducing waste through extension of shelf life; the difficulty involves the drive for clean labels and the removal of preservatives and the apparent demand for natural products with minimal technological intervention without compromising product quality and convenience while extending shelf life. This is some challenge!

This is, of course, just one of the aspects identified through the consultation, and there is continued interest in using engineering and technology solutions to reduce waste. One such project that we have recently completed highlights how the energy efficiency of bakery ovens can be improved by about 5% by balancing the flow of gases into and out of the ovens (Anonymous 2015b).

Industry Skills and Knowledge

One of the main issues raised during the consultation was the need to address a perceived growing skills shortage in the sector. The food and drinks industry has changed significantly over the past 25 years or so. Supply chains are global and complex, demanding much more sophisticated management systems. The range of raw materials and ingredients now used is far more diverse. Specifications are more complex. Improved analysis and testing has made us aware of previously undiscovered and emerging hazards and risks that need to be managed. Regulatory controls—both voluntary and legislative—have grown in complexity and reach. Many of today’s industry leaders and senior managers have grown up with these changes and had the luxury of adapting and developing over a period of time, but are also now in later career and heading toward retirement. New entrants to the industry are faced with a sector of almost bewildering complexity. Schools and universities are doing their best to equip them with the necessary underpinning knowledge and skills, but there is no substitute for experience.

At the same time, the industry is not necessarily perceived as a glamorous career option for science graduates compared to say medicine or engineering. Professional bodies are working hard to raise the profile of the profession, but the needs discussion also highlighted the requirement for science and technology organizations to promote the wide range of roles on offer to scientists, technologists, and engineers from across the spectrum. At Campden BRI we are working closely with the UK Institute of Food Science and Technology on a range of initiatives such as FoodStart (foodstart.org.uk) and Student LaunchPad (ifst.org/communities-students/student-launchpad) to promote the sector, as well as with local schools to provide insight into the fascinating and interdisciplinary nature of food science and technology. We are also working with the Institute of Food Technologists through the British Section as well as offering the first European approved Certified Food Scientist (CFS) preparatory course.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

What Happens Next?

What Happens Next?

The industry needs document (Campden BRI 2015) is a statement of needs—what it is that the food and drink supply chain needs from science, technology, and their practical application—in order to continue delivering safe and wholesome products that meet the needs and wants of consumers. It has been published and distributed widely to encourage its use both by industry and the science and technology supply chain. The three main areas of follow-up activity are as follows.

At Campden BRI, it is being used to shape the member-funded research program and help inform the range of scientific, technical, and knowledge-based activities that are provided for members.

The Campden BRI team is working with government departments, agencies, funding bodies, standards organizations, universities, and research institutes to help stimulate and inform new approaches in the application of science and technology.

Member companies are using the document to review their own needs—from their own perspective in the supply chain or their sub-sector—to help shape their own technical strategies.

It is our aspiration that all stakeholders in the food, drinks, and allied industries will find it useful in stimulating innovation and meeting consumer needs.

The Consultation Exercise

Campden BRI consulted its 2,400 member companies across 75 countries through a variety of activities between March and November 2014. These included face-to-face input from more than 500 industry representatives at meetings of its 13 member interest groups, an electronic survey, gathering of collective intelligence through extensive day-to-day contact with members and clients, and drawing on third-party strategies.

Colin Kelly, director of research & development, Warburtons, had this to say about the research project. “Understanding what the food industry needs from science and technology is vital to driving innovation that will benefit consumers,” said Kelly. “The Campden BRI needs consultation—the biggest of its kind and spanning the whole supply chain—provides fantastic insight. It is helping us at Warburtons to shape our innovation strategy, and I believe it will prove invaluable to government and funding bodies in taking account of industry needs. It will also catalyze innovative partnerships between industry and science providers to deliver real benefits.”

This is the seventh time that the consultation, which was first undertaken in 1996 and is now conducted every three years, was carried out.

Major Needs Identified in the Consultation

Through the consultation, a number of recurring needs arose that were common to different parts of the supply chain or from distinct but related drivers. They include the following:

■ Assuring product safety, which is seen as an imperative, through the availability of the necessary assurance and analytical tools

■ Encouraging consumer well-being through a healthy diet

■ Protecting industry and consumers from food fraud

■ Encouraging sustainable practices such as better crop protection and reduced use of resources

■ Tackling industry’s skills shortage

What Is Driving Industry Needs

The consultation revealed six main drivers for needs identified by industry:

➊ Safety—assuring the safety of food and drink products

➋ Quality and value—delivering products of intended quality at proportionate cost

➌ Nutrition, health, and well-being—delivering nutritious products that meet dietary needs

➍ Resilience and efficiency—assuring an adequate supply while protecting the supply chain and consumers from food fraud

➎ Environmental sustainability—minimizing waste and environmental impact at all stages

➏ Skills and knowledge—developing and maintaining the skills and knowledge needed for an effective and efficient food and drink production system

Sam Millar, a professional member of IFT, is director of technology at Campden BRI, Chipping Campden, United Kingdom, the world’s largest membership-based food and drink research organization ([email protected]).

References

Anonymous. 2015a. “Top 10 UK Retailers—Grocery.” Retail Economics. http://www.retaileconomics.co.uk/top10-retailers-grocery.asp.

Anonymous. 2015b. “New Campden BRI Research Improves Oven Efficiency Saving Up to £14,000 on Running Costs. http://www.campdenbri.co.uk/case/oven-efficiency-saving.php.

Gibbons, L. 2014. “Big Four Retailers Will Never Beat Aldi on Price.” Food Manufacture, Oct.6. http://www.foodmanufacture.co.uk/Business-News/Major-retailers-will-never-beat-discounters.

Campden BRI. 2015. “Innovation for the Food and Drink Supply Chain: Scientific and Technical Needs 2015-17.” Campden BRI, Chipping Campden, UK. campdenbri.co.uk.

FSA. 2013. “UK Public Gambling With Their Guts.” Press release, June 10. Food Standards Agency, London. food.gov.uk.

FSA. 2014. “Timeline on Horse Meat Issue.”

IFST. 2015a. Foodstart. Institute of Food Science & Technology, London. foodstart.org.uk.

IFST. 2015b. Student LaunchPad. ifst.org.

Leathers, R. 2104. TACCP—Threat Assessment and Critical Control Point: A Practical Guide. Campden BRI Guideline 72. Campden BRI, Chipping Campden, UK. ISBN 978 0907503 77 4.

Pendrous, R. 2014. “FSA Restructures to Ensure Food Crime Unit Capability.” Food Manufacture, Sept. 8.

Stanley, Richard. 2014. Sustainable Crop Protection. Campden BRI.