Ohio State Charts a Functional Path to Target Cancer

INSIDE ACADEMIA

Food, nutrition, and health are intricately linked, and as food becomes more abundant, so does obesity, which is expected to surpass tobacco use as the leading preventable cause of cancer. In the United States alone, 1.7 million people are diagnosed with cancer each year, and 600,000 of them die from it. Yet some cancer research continues to involve conventional methods and segregated investigative techniques to identify a single drug or compound that can cure or effectively manage cancer. Ohio State University has a more novel approach: Through integral collaborations among its food science, agriculture, medicine, and nutrition experts, researchers at Ohio State’s Food Innovation Center (FIC), Center for Advanced Functional Foods Research and Entrepreneurship (CAFFRE), and Comprehensive Cancer Center–James Cancer Hospital are on a mission to prevent cancer with foods. These innovative scientists are developing functional foods that may help prevent and manage cancer and other chronic diseases by harnessing the power of phytochemicals found in whole foods.

Natural Defenses

Professor Steven Schwartz, director of the CAFFRE and associate director of the FIC, explains that phytochemicals are plants’ natural defenses against predators and disease: “The only defense systems plants have is their metabolites—their phytochemicals. [Phytochemicals] are a complex group of compounds that plants have developed to fight diseases.” Those same defense mechanisms that plants use to fight disease also appear to be effective at fighting diseases in humans. For example, research suggests that certain carotenoids inhibit the growth of cancer cells and improve the body’s immune response. Indoles and glucosinolates help detoxify carcinogens, limit the production of cancer-related hormones, and impede the growth of tumors. Isoflavones obstruct tumor growth and limit the production of cancer-related hormones. And polyphenols prevent the formation of cancer cells and reduce inflammation. “There is great potential to consider plant bioactive compounds—in particular, phytochemicals—to prevent disease and enhance health. There are so many biologically active components in plants that are yet unstudied and untapped. We’re only just scraping the surface in finding out that certain plant foods in the diet can inhibit certain diseases,” says Schwartz.

Professor Steven Schwartz, director of the CAFFRE and associate director of the FIC, explains that phytochemicals are plants’ natural defenses against predators and disease: “The only defense systems plants have is their metabolites—their phytochemicals. [Phytochemicals] are a complex group of compounds that plants have developed to fight diseases.” Those same defense mechanisms that plants use to fight disease also appear to be effective at fighting diseases in humans. For example, research suggests that certain carotenoids inhibit the growth of cancer cells and improve the body’s immune response. Indoles and glucosinolates help detoxify carcinogens, limit the production of cancer-related hormones, and impede the growth of tumors. Isoflavones obstruct tumor growth and limit the production of cancer-related hormones. And polyphenols prevent the formation of cancer cells and reduce inflammation. “There is great potential to consider plant bioactive compounds—in particular, phytochemicals—to prevent disease and enhance health. There are so many biologically active components in plants that are yet unstudied and untapped. We’re only just scraping the surface in finding out that certain plant foods in the diet can inhibit certain diseases,” says Schwartz.

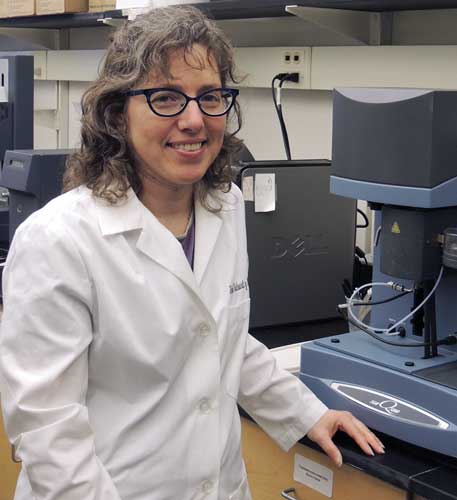

Schwartz, a food toxicologist, collaborates with professor Steven Clinton, a medical oncologist at the James and associate director of FIC and CAFFRE, and professor Yael Vodovotz to create foods that reduce the risk of cancer, including a tomato-soy juice, a berry-based confection, and a soy-based bread. Schwartz and Clinton met a number of years ago when both worked at different research institutions (Schwartz at North Carolina State University; Clinton at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School). Schwartz was interested in studying the effects of bioactive components in food on cancer and other chronic diseases, and Clinton, who holds doctorate degrees in both medicine and nutrition, was investigating the relationship between diet, nutrition, and cancer. By the time they arrived at Ohio State, the two had already begun cooperatively exploring specific bioactive plant compounds and their therapeutic effects. Vodovotz, who specializes in the physical, chemical, and functional properties of foods, arrived later. Having developed foods for space missions, she was singled out by Schwartz as the ideal person to help realize the concept of chemopreventive foods. The three scientists also work with a network of Ohio State researchers from various disciplinary areas.

Schwartz, a food toxicologist, collaborates with professor Steven Clinton, a medical oncologist at the James and associate director of FIC and CAFFRE, and professor Yael Vodovotz to create foods that reduce the risk of cancer, including a tomato-soy juice, a berry-based confection, and a soy-based bread. Schwartz and Clinton met a number of years ago when both worked at different research institutions (Schwartz at North Carolina State University; Clinton at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School). Schwartz was interested in studying the effects of bioactive components in food on cancer and other chronic diseases, and Clinton, who holds doctorate degrees in both medicine and nutrition, was investigating the relationship between diet, nutrition, and cancer. By the time they arrived at Ohio State, the two had already begun cooperatively exploring specific bioactive plant compounds and their therapeutic effects. Vodovotz, who specializes in the physical, chemical, and functional properties of foods, arrived later. Having developed foods for space missions, she was singled out by Schwartz as the ideal person to help realize the concept of chemopreventive foods. The three scientists also work with a network of Ohio State researchers from various disciplinary areas.

From the Crops to the Clinic

Collectively, their objective is to enhance the disease-fighting properties of foods that people can eat every day; bread, tomato juice, and candy fall into this category. Tomatoes are rich in lycopene and other carotenoids, soybeans are good sources of isoflavones and other flavonoids, and berries are bursting with polyphenols. Even though research indicates that these foods and phytochemicals are associated with a reduced risk of cancer, their effectiveness is not all-inclusive. “The roles of dietary patterns or foods that have cancer prevention properties may be unique to specific types of cancer,” says Clinton. The tomato-soy juice was thus specifically formulated to target prostate cancer. “Both tomatoes and soy in the diet are epidemiologically linked with the reduced risk of prostate cancer,” Schwartz says. “This particular product that we’ve developed is actually derived from a high-lycopene variety of tomatoes because it’s the lycopene in the tomato that’s thought to be … the etiologic agent involved in decreasing prostate cancer risk.” That tomato variety was created by David Francis, a scientist in Ohio State’s department of horticulture and crop science.

Besides specially bred tomatoes, the juice contains only part of the soybean: the soy germ, which contains only isoflavones. Vodovotz indicates that using only the soy germ was strategic in terms of making the product more palatable. “Whole soy contains protein, which is nice except that it makes for a very viscous product, so the tomato juice would be more like a tomato sauce,” she says, and that would not be optimal for drinking. In addition, soy has an unpleasant taste, and tomatoes effectively mask its flavor. “Food scientists are experts at creating food products—using their enormous array of tools—that taste good. We have used the same kind of approaches as we design food products for cancer prevention. After all, if someone won’t eat it and consume it, we’re never going to be able to test whether it has anti-cancer activity,” says Clinton. “The tomato-soy juice took months, if not a couple of years, of going from something that initially was like tomato juice with chalk in it to something that participants readily consumed in our clinical trials,” he adds. Palatability was also a concern for the soy bread products Vodovotz created to target prostate cancer as well as hypercholesterolemia. As a consequence, reformulating the soy breads for optimal taste, texture, and phytochemical dose/activity also took several years.

Besides specially bred tomatoes, the juice contains only part of the soybean: the soy germ, which contains only isoflavones. Vodovotz indicates that using only the soy germ was strategic in terms of making the product more palatable. “Whole soy contains protein, which is nice except that it makes for a very viscous product, so the tomato juice would be more like a tomato sauce,” she says, and that would not be optimal for drinking. In addition, soy has an unpleasant taste, and tomatoes effectively mask its flavor. “Food scientists are experts at creating food products—using their enormous array of tools—that taste good. We have used the same kind of approaches as we design food products for cancer prevention. After all, if someone won’t eat it and consume it, we’re never going to be able to test whether it has anti-cancer activity,” says Clinton. “The tomato-soy juice took months, if not a couple of years, of going from something that initially was like tomato juice with chalk in it to something that participants readily consumed in our clinical trials,” he adds. Palatability was also a concern for the soy bread products Vodovotz created to target prostate cancer as well as hypercholesterolemia. As a consequence, reformulating the soy breads for optimal taste, texture, and phytochemical dose/activity also took several years.

Unpleasant tastes or flavors were not an issue for the black raspberry confection that Vodovotz helped develop to target oral cancers related to tobacco smoking. According to Vodovotz, the anticancer compounds in black raspberries may change genes mutated by tobacco smoke to resemble the normal genes of nonsmokers. She also is working on the development of a confection containing concentrated amounts of a bioactive compound from another fruit. Naringenin, a flavonoid that is abundant in grapefruit, may mitigate some of the causes of obesity that can lead to breast cancer. The grapefruit confection is still in the early stages of testing, but Vodovotz is highly optimistic as her work at Ohio State and collaborations with other departments adhere to a widely held perspective. “Food is a better vehicle than single compounds or pharmaceuticals in the case of some of these bioactives. In addition, incorporating [functional foods] into a regular diet is the best way to achieve prevention goals,” she says.

Unpleasant tastes or flavors were not an issue for the black raspberry confection that Vodovotz helped develop to target oral cancers related to tobacco smoking. According to Vodovotz, the anticancer compounds in black raspberries may change genes mutated by tobacco smoke to resemble the normal genes of nonsmokers. She also is working on the development of a confection containing concentrated amounts of a bioactive compound from another fruit. Naringenin, a flavonoid that is abundant in grapefruit, may mitigate some of the causes of obesity that can lead to breast cancer. The grapefruit confection is still in the early stages of testing, but Vodovotz is highly optimistic as her work at Ohio State and collaborations with other departments adhere to a widely held perspective. “Food is a better vehicle than single compounds or pharmaceuticals in the case of some of these bioactives. In addition, incorporating [functional foods] into a regular diet is the best way to achieve prevention goals,” she says.

Diet, Functional Foods, and Public Health

Finding ways to mass produce such functional foods and incorporate them into the daily diet of all Americans may seem like a logical step, but these foods may not be marketable to the general public nor do they have relevance for public health guidelines. “Dietary patterns that have a foundation in a plant-based diet—a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains—these seem to be associated with a lower risk of many types of cancer. We would like to have the mechanistic understanding of how that works in order to have a stronger rationale for defining public health goals, changing public policy, perhaps even providing guidance to industry,” says Clinton, who sits on the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. “I do not think that functional foods will be part of Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Dietary Guidelines for Americans is a critical process for a public health approach for the nation as a whole,” he says.

Clinton emphasizes that the effectiveness of a functional food is dependent on a myriad of specific individual factors, including a person’s genes, family history, metabolism, gut microflora, and so on. With the dietary guidelines, “we are providing the best possible information every five years based on accumulating science that says this is the optimal dietary pattern for everyone,” Clinton explains. For functional foods, “we switch from the public health approach to the individual approach, or you may even call that a medical model, where our strategy is to target each person as an individual,” he says. For this level of specificity, cost is a significant issue: “I’m not sure [food companies] are willing to put the research dollars into proving that functional foods are in fact efficacious,” Schwartz surmises.

A Model for the Future

A Model for the Future

Ohio State’s distinctive collaboration of scientists across different disciplines serves as a paradigm for the development of truly purposeful functional foods. “The collaborative program that we have here at Ohio State, I think, is quite unique just from the fact that there are few land-grant institutions in the nation that have both a college of agriculture and a college of medicine within the same campus boundary. … It’s really what has made this collaborative arrangement work so well,” Schwartz says. The level of teamwork that Ohio State has achieved is just one aspect of its special approach to functional foods. Clinton highlights another: “We have created novel foods that [have been] used in human studies. We’ve shown how components that are found in these foods are absorbed, metabolized, and potentially distributed to the target tissues. This is the kind of work that is a prelude to what we really need, which are large-scale multi-institutional human studies. We may have very strong data from laboratory animal models or cells in culture, but ultimately (just like a new drug to treat cancer) if we’re definitively going to say that a food may alter risk, we need to do … large phase III trials,” he asserts.

Phase I and phase II clinical trials, which involved consumption of the products by cancer patients over a period of one to four months and monitoring several biomarkers, have been completed on the soy breads and tomato-soy juice. The results will be published in the next year. In the meantime, Ohio State’s researchers are expanding their portfolio, developing foods to fight obesity, Alzheimer’s disease, and vitamin A deficiency as well as more foods for chemoprevention. Clearly, the researchers at Ohio State are charting new paths in the fight against cancer and other diseases.

Toni Tarver is senior writer/editor of Food Technology magazine ([email protected]).