Substantiating Label Claims

FOOD SAFETY & QUALITY

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers a food or dietary supplement to be misbranded if its label—including the brand name, vignettes, logos, containers, wrappers, and other information accompanying the food—is false or misleading in any way. As described in the FDA’s Guidance for Industry: A Food Labeling Guide, the agency allows several types of claims on labels of food and dietary supplements.

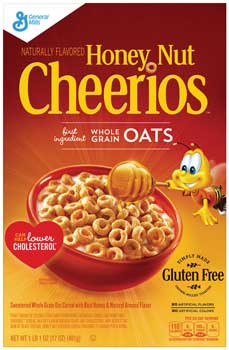

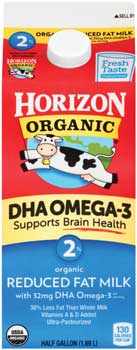

• Nutrient Content Claims. The Nutrition Labeling and Education Act permits the use of label claims that characterize the level of a nutrient in a food if they have been authorized by the FDA and are made in accordance with the FDA’s authorizing regulations. Nutrient content claims describe the level of a nutrient in a product, using terms such as “free,” “high,” and “low,” or they compare the level of a nutrient in a food to that of another food, using terms such as “more,” “reduced,” and “lite.” An accurate quantitative statement such as “200 mg of sodium” that does not otherwise characterize the nutrient level may be used to describe the amount of a nutrient present. However, a statement such as “only 200 mg of sodium” implies that the level is low, and the food would have to meet the nutritional criteria for a low-nutrient content claim or carry a disclosure statement that it does not qualify for the claim. Most nutrient content claim regulations apply only to those nutrients that have an established Daily Value. Percentage claims describe the percentage of a dietary ingredient in a dietary supplement.

Implied claims suggest that a nutrient or ingredient is absent from or present in a certain amount of the product or that a food may be useful in maintaining healthy dietary practices (e.g., “healthy, contains 3 grams of fat”). The terms “healthy, “health,” “healthful,” “healthfully,” “healthfulness,” “healthier,” “healthiest,” “healthily,” and “healthiness” may be used if the food meets the requirements for total fat, saturated fat, sodium, and cholesterol. The food must also contain a certain amount of either vitamin A, vitamin C, calcium, iron, protein, or fiber.

Claims generally not considered implied claims include avoidance claims for religious, food-intolerance, or other non-nutrition-related reasons (e.g., “100% milk free”); statements about non-nutritive substances (e.g., “no artificial colors”); added-value statements (e.g., “made with real butter”); statements of identity (e.g., “corn oil margarine”); and special dietary statements made in compliance with a specific provision.

• Health Claims. These claims describe a relationship between 1) a food, food component, or dietary supplement ingredient and 2) reduced risk of a disease or health-related condition. A statement lacking either of these is not considered a health claim. A health claim must meet criteria authorized by an FDA regulation based on an extensive review of scientific literature, using the significant-scientific-agreement standard to determine whether the substance-disease relationship is well established. In response to a petition or on its own initiative, the FDA can issue a regulation authorizing a health claim for a food or dietary supplement after reviewing and evaluating the scientific evidence, or a health claim for food other than dietary supplements can be based on an authoritative statement of the National Academy of Sciences or other scientific body of the U.S. government with responsibility for public health protection or nutrition research. A company can use a claim 120 days after notifying the FDA unless the agency has stated that the notification doesn’t include all the required information (namely, the exact wording of the claim, a concise description of the basis for determining that the requirements for an authoritative statement have been satisfied, a copy of the authoritative statement, and a balanced representation of the scientific literature relating to the nutrient level for the claim).

Health claims that have been authorized by FDA regulation include the relationships between calcium and osteoporosis; calcium, vitamin D, and osteoporosis; dietary fat and cancer; sodium and hypertension; dietary saturated fat, cholesterol, and risk of coronary heart disease; fiber-containing grain products and cancer; fruits, vegetables, and grain products that contain fiber and risk of coronary heart disease; fruits and vegetables and cancer; and folate and neural tube defects.

• Qualified Health Claims. When there is emerging evidence for a relationship between a food substance and reduced risk of a disease or health-related condition but the evidence is not established enough to meet the significant-scientific-agreement standard for the FDA to issue an authorizing regulation, a company can ask the agency to review the scientific evidence and permit use of a qualified claim. If the FDA finds that the evidence supporting the proposed claim is credible and the claim can be qualified to prevent it from misleading consumers, the agency issues a letter of enforcement discretion, specifying the qualifying language that should accompany the claim.

• Structure/Function Claims. These statements address a role of a specific nutrient or dietary ingredient in maintaining normal healthy structures or functions of the body (e.g., “calcium builds strong bones”) or the mechanism by which a nutrient or dietary ingredient acts to maintain structures or functions of the body (e.g., “fiber maintains bowel regularity”). Unlike health claims, structure/function claims for conventional foods focus on effects derived from nutritive value. The agency does not require conventional food manufacturers, distributors, or packers to notify the FDA about their structure/function claims, and disclaimers are not required for such claims on conventional foods.

• Natural. On November 12, 2015, the FDA requested comments on whether and how to define “natural” and how it should be used on food labels. The deadline for comments has been extended to May 10, 2016.

• Gluten-Free. On February 23, 2016, the FDA extended to April 25, 2016, the deadline for comments on its November 18, 2015, proposal regarding gluten-free labeling for foods that are fermented or hydrolyzed or contain fermented or hydrolyzed ingredients. The proposal provides alternative means for the agency to verify compliance based on manufacturers’ records.

• Gluten-Free. On February 23, 2016, the FDA extended to April 25, 2016, the deadline for comments on its November 18, 2015, proposal regarding gluten-free labeling for foods that are fermented or hydrolyzed or contain fermented or hydrolyzed ingredients. The proposal provides alternative means for the agency to verify compliance based on manufacturers’ records.

• Non-Genetically Engineered. On November 19, 2015, the FDA issued guidance on voluntary labeling of foods and feed to indicate whether or not they have been derived from genetically engineered plants and announced the availability of a draft guidance for food manufacturers who want to voluntarily label their food or feed products or ingredients to indicate whether or not they contain products made with AquAdvantage Salmon, which is genetically engineered.

• Allergens. The Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act requires food manufacturers to label food products that contain an ingredient that is or contains protein from a major food allergen. The eight major food allergens are milk, eggs, fish, Crustacean shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, and soybeans. The FDA routinely inspects a variety of packaged foods to ensure that they are properly labeled.

• Allergens. The Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act requires food manufacturers to label food products that contain an ingredient that is or contains protein from a major food allergen. The eight major food allergens are milk, eggs, fish, Crustacean shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, and soybeans. The FDA routinely inspects a variety of packaged foods to ensure that they are properly labeled.

• Omega-3 Fatty Acids. On February 23, 2016, the FDA announced the availability of a compliance guide to help small entities comply with the final rule regarding nutrient content claims for alpha-linolenic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid, and docosahexaenoic acid.

U.S. Dept. of Agriculture

The Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) of the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture (USDA) is responsible for ensuring that the labeling of meat and poultry products is truthful and not misleading. Labeling includes any written, printed, or graphic material that is used on the containers or wrapping of meat and poultry products or that accompanies meat and poultry products at their point of sale. Labels bearing claims are evaluated by the FSIS prior to use.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

• Organic. The USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service develops regulations specifying the requirements for labeling products as “100 percent organic,” “organic,” and “made with organic _____” and whether the USDA organic seal can be used. USDA organic products must be produced without the use of excluded methods (genetic engineering, ionizing radiation, or sewage sludge) and must be certified by a USDA-accredited certifying agent, following all USDA organic regulations. If a product has not been certified as organic by a certifying agent, the manufacturer can’t make any organic claim on the principal display panel or use the seal, but it can identify the certified organic ingredients as organic with their percentage on the information panel.

• Non-Genetically Engineered. For a food to be sold or labeled as “100% organic,” “organic” or “made with organic _____,” it must be produced and handled without the use of genetic engineering. A non-genetically engineered statement can be used on the label of meat and poultry products that qualify as USDA organic. A company can state on the label that it has not used genetically engineered ingredients or feed if it notifies the FSIS and provides the approval number for the current organic label, a copy of the current label, and the proposed statement. The label must include a disclaimer such as “The beef used in this product is fed a diet that contains non-genetically engineered ingredients. The USDA organic regulations prohibit the use of genetically engineered feed ingredients.”

• Fresh. The claims “fresh,” “not frozen,” and similar terms cannot be used to describe cured products such as corned beef, smoked cured turkey, or prosciutto; canned, hermetically sealed, shelf-stable, dried, or chemically preserved products; raw, injected, basted, or marinated poultry whose internal temperature has ever been below 26°F; finished processed poultry products, such as turkey sausage and chicken meatballs, whose internal temperature has ever been below 26°F; uncured red meat products treated with a substance, such as ascorbic acid, that delays discoloration; and products treated with an antimicrobial or irradiation.

A term such as “never frozen” is not permitted on raw or processed poultry products whose internal temperature has ever been below 0°F, red meat products that have ever been frozen, and refrigerated secondary products such as multicomponent pizzas and dinners whose meat or poultry component has ever been frozen. However, these secondary products can be labeled as “fresh” as long as the product is not or has not previously been frozen and the term is used to describe the product as a whole even when made from the components mentioned above. Trademarks, company names, and fanciful names containing the word “fresh” are acceptable even on the products mentioned above, as long as it is clear to the consumer that the product is not fresh.

• Natural. The FSIS allows use of the term “natural” when products contain no artificial ingredients and are no more than minimally processed. It can be used in combination with the claim “certified organic by _____” when the requirements for the claim “organic” are met.

• Unapprovable Claims. The FSIS does not allow use of such unapprovable claims as “antibiotic-free,” “hormone-free,” “residue-free,” “residue-tested,” “naturally raised,” “naturally grown,” “drug-free,” “chemical-free,” “organic,” and “organically raised.”

• Animal Production Claims. The FSIS permits use of statements on the labeling of meat and poultry products that tell how the animals were raised (e.g., “raised without added hormones,” “raised without antibiotics,” “free range,” etc.). The FSIS evaluates supporting documentation, such as producer affidavits and raising protocols, to ensure the truthfulness and accuracy of the claims. On January 12, 2016, the USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service withdrew its standards for “grass-fed” and “naturally raised” livestock claims since a company wanting to use the claim must receive pre-approval from the FSIS.

• Animal Production Claims. The FSIS permits use of statements on the labeling of meat and poultry products that tell how the animals were raised (e.g., “raised without added hormones,” “raised without antibiotics,” “free range,” etc.). The FSIS evaluates supporting documentation, such as producer affidavits and raising protocols, to ensure the truthfulness and accuracy of the claims. On January 12, 2016, the USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service withdrew its standards for “grass-fed” and “naturally raised” livestock claims since a company wanting to use the claim must receive pre-approval from the FSIS.

Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau

The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) is a bureau of the U.S. Department of the Treasury that in 2003 took over the responsibilities of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives related to the manufacture, wholesale, and importation of alcohol and tobacco and the labeling of alcohol beverages. The Federal Alcohol Administration Act set standards for regulating the labeling and advertising of wine containing at least 7% alcohol by volume, distilled spirits, and malt beverages. The TTB provides preclearance of advertising material at a company’s request. It also monitors the marketplace to ensure compliance with the alcohol beverage advertising regulations, selecting ads from a variety of media and looking for statements that are false, misleading, or deceptive; prohibited uses of the word “pure” for distilled spirits; misleading or false curative or therapeutic claims; misleading references to carbohydrates, calories, fat, protein, and other macronutrients or components; and specific health claims and health-related statements. When reviewing labeling and advertising claims, it analyzes samples of products to validate calorie, fat, carbohydrate, and protein statements.

• Organic. If a bottler or importer uses the word “organic” in any fashion likely to be perceived as claiming that a product or anything associated with it is organically produced, contains organic ingredients, or was processed in an organic manner or facility, the TTB will consider it an organic claim and apply the requirements of the USDA’s organic regulations. An alcohol beverage can be labeled “100% organic” if it contains only organic ingredients and processing aids with no chemically added sulfites, “organic” if it contains at least 95% organic ingredients with no chemically added sulfites, and “made with organic ____” if it contains at least 70% organic ingredients and no more than 100 ppm of sulfites from sulfur dioxide. Products containing less than 70% organic ingredients and products not processed by a certified organic handling operation may only identify organic ingredients in the ingredients statement. Wine containing any added sulfites is eligible only for the “made with” labeling category and may not use the USDA organic seal. Sulfites may be added only to wine “made with” organic grapes. Organic labels must be reviewed by an organic certifying agent and the TTB.

• Organic. If a bottler or importer uses the word “organic” in any fashion likely to be perceived as claiming that a product or anything associated with it is organically produced, contains organic ingredients, or was processed in an organic manner or facility, the TTB will consider it an organic claim and apply the requirements of the USDA’s organic regulations. An alcohol beverage can be labeled “100% organic” if it contains only organic ingredients and processing aids with no chemically added sulfites, “organic” if it contains at least 95% organic ingredients with no chemically added sulfites, and “made with organic ____” if it contains at least 70% organic ingredients and no more than 100 ppm of sulfites from sulfur dioxide. Products containing less than 70% organic ingredients and products not processed by a certified organic handling operation may only identify organic ingredients in the ingredients statement. Wine containing any added sulfites is eligible only for the “made with” labeling category and may not use the USDA organic seal. Sulfites may be added only to wine “made with” organic grapes. Organic labels must be reviewed by an organic certifying agent and the TTB.

• Health Claims. Claims regarding health benefits associated with the consumption of alcohol beverages cannot be made on labels or in ads unless the claim is properly qualified, balanced, sufficiently detailed, and specific and outlines the categories of individuals for whom any positive health effects would be outweighed by numerous negative health effects.

• Allergen Labeling. The TTB also requires labeling that indicates whether a product may contain any of the major food allergens.

Federal Trade Commission

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) regulates advertising for foods, over-the-counter drugs, dietary supplements, medical devices, and cosmetics. The TTB has jurisdiction over deceptive or misleading alcohol labeling and advertising, but the FTC can also take action if an ad for alcohol beverages is deceptive or misleading. Before a company runs an ad that makes health or safety claims, the claim must be supported by scientific evidence that has been evaluated by experts qualified to review it. While the FTC doesn’t review a company’s ad before it runs, it does provide guidance on how it evaluates claims made in food ads in its “Enforcement Policy Statement on Food Advertising" and "Dietary Supplements: An Advertising Guide for Industry.”

Neil H. Mermelstein, IFT Fellow, Editor Emeritus of Food Technology

Neil H. Mermelstein, IFT Fellow, Editor Emeritus of Food Technology

[email protected]