Tackling Food Issues on a UMass Scale

INSIDE ACADEMIA

In the year 1900, the life expectancy of a man in the United States was 48 years and that of a U.S. woman was 51 years. Since then the life expectancies of U.S. men and women have increased to 76 and 81, respectively. Nonetheless, the steady increase in lifespan has not translated into an increase in health span. In fact, while morbidity and mortality caused by communicable diseases have decreased exponentially, the incidence of noncommunicable chronic disease continues to rise, escalating the number of Americans who live longer but with more illness and disability. And while some say that processed food is a significant culprit for this dichotomy, distinguished professor Fergus Clydesdale at the University of Massachusetts Amherst (UMass Amherst) provides a different perspective: “Food science is very similar to medicine. The science is very similar, but … food science in many ways has done much more good than medicine has over the years. If you look at the tremendous change in lifespan, which many people attribute to medicine, … I believe it is more due … to food safety and processed foods,” he says. Moreover, Clydesdale believes that food science is the only way to shift the tide of crucial problems encumbering a rapidly changing world.

In the year 1900, the life expectancy of a man in the United States was 48 years and that of a U.S. woman was 51 years. Since then the life expectancies of U.S. men and women have increased to 76 and 81, respectively. Nonetheless, the steady increase in lifespan has not translated into an increase in health span. In fact, while morbidity and mortality caused by communicable diseases have decreased exponentially, the incidence of noncommunicable chronic disease continues to rise, escalating the number of Americans who live longer but with more illness and disability. And while some say that processed food is a significant culprit for this dichotomy, distinguished professor Fergus Clydesdale at the University of Massachusetts Amherst (UMass Amherst) provides a different perspective: “Food science is very similar to medicine. The science is very similar, but … food science in many ways has done much more good than medicine has over the years. If you look at the tremendous change in lifespan, which many people attribute to medicine, … I believe it is more due … to food safety and processed foods,” he says. Moreover, Clydesdale believes that food science is the only way to shift the tide of crucial problems encumbering a rapidly changing world.

The idea that processed food has been and will be a panacea of sorts for modern ills is not a popular viewpoint. To the contrary, certain cancers, cardiovascular disease, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and stroke have frequently been described as the consequences of a steady diet of processed foods. But according to Clydesdale, condemning processed foods is ill-advised and misleading. “The term ‘processed’ has become such a pejorative term, and that’s really unfortunate,” Clydesdale says. “People don’t understand that it’s the composition of the foods you eat, not how they’re processed or cooked.” To illustrate his point, he gives the example of Scottish shortbread, which he calls one of the tastiest desserts in the world. “It’s made of sugar and butter and a tiny bit of flour—and that’s it. Now that was baked on a wood stove in northern Ontario in our kitchen. It looked lovely and it was natural,” he says. “If you ate a piece of shortbread after dinner, it would never hurt you, but if you ate shortbread all day long, it would be very bad for you.” Hence, even natural, unprocessed foods can cause obesity or other chronic diseases.

The idea that processed food has been and will be a panacea of sorts for modern ills is not a popular viewpoint. To the contrary, certain cancers, cardiovascular disease, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and stroke have frequently been described as the consequences of a steady diet of processed foods. But according to Clydesdale, condemning processed foods is ill-advised and misleading. “The term ‘processed’ has become such a pejorative term, and that’s really unfortunate,” Clydesdale says. “People don’t understand that it’s the composition of the foods you eat, not how they’re processed or cooked.” To illustrate his point, he gives the example of Scottish shortbread, which he calls one of the tastiest desserts in the world. “It’s made of sugar and butter and a tiny bit of flour—and that’s it. Now that was baked on a wood stove in northern Ontario in our kitchen. It looked lovely and it was natural,” he says. “If you ate a piece of shortbread after dinner, it would never hurt you, but if you ate shortbread all day long, it would be very bad for you.” Hence, even natural, unprocessed foods can cause obesity or other chronic diseases.

It would be foolish to doubt his reasoning: During a food science career that extends beyond five decades, Clydesdale performed research on plant pigments, the effects of processing on food and its constituents, food fortification, the bioavailability of nutrients, and nutrient deficiencies. So he certainly knows what he is talking about. And even though Clydesdale advocates the high value of processed foods, he also appreciates local fresh food. “I don’t know a scientist who doesn’t really enjoy fresh food. When it’s available, I buy all local food; I buy it right off the farm stands. It tastes better, it looks better, and it’s probably more nutritious. But you can’t have that all year long. In order to have that in January in Amherst, you’d probably have to drink a couple of bottles of scotch to imagine that it’s there,” Clydesdale says.

He is perhaps best known for being one of the first food scientists to integrate food science, nutrition, and public policy. Consequently, in the effort to reduce the incidence of chronic disease, Clydesdale thinks all three (food science, nutrition, and food policy) are important. When the concept of food science emerged more than a century ago, the field was focused predominantly on preserving food, processing food, and increasing food safety. But Clydesdale’s research led to the recognition that food science and nutrition were intertwined. “I think it’s a natural integration. If we study nutrition to find out how we can better human health and we study food science to find out how we can better health through processing, safety, and making food more nutritious, then those two have to fit together,” he explains. “I don’t think you can separate one from the other. We have to know the nutrition facts, and how they affect chronic disease, but then we have to have food science, which takes some of those facts and is able to isolate the compounds that are responsible, evaluate their bioavailability, and get them into a form that people can eat.”

Clydesdale’s thoughtful approach to food science has made an indelible impression in academia, government, and industry: He has been asked to consult with a number of food companies and has been appointed to committees with the U.S. Senate, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, the National Academies of Sciences, and the National Cancer Institute. Furthermore, in 2011 UMass Amherst established the Fergus M. Clydesdale Center for Foods for Health and Wellness. The center was created to enhance the nutrition and health benefits of foods, combat chronic disease, improve methodologies, develop new technologies, and inform food policy. “[A university committee] decided that the answer to a lot of our problems worldwide with food was to have a center that concentrated on bringing together nutrition, food science, and policy and then bringing that molecular and scientific knowledge to the point where it could be passed on to industry,” Clydesdale explains. “Much to my chagrin, they decided to call it the [Fergus M.] Clydesdale Center for Foods for Health and Wellness. I was very interested in having a different name.”

Clydesdale’s thoughtful approach to food science has made an indelible impression in academia, government, and industry: He has been asked to consult with a number of food companies and has been appointed to committees with the U.S. Senate, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, the National Academies of Sciences, and the National Cancer Institute. Furthermore, in 2011 UMass Amherst established the Fergus M. Clydesdale Center for Foods for Health and Wellness. The center was created to enhance the nutrition and health benefits of foods, combat chronic disease, improve methodologies, develop new technologies, and inform food policy. “[A university committee] decided that the answer to a lot of our problems worldwide with food was to have a center that concentrated on bringing together nutrition, food science, and policy and then bringing that molecular and scientific knowledge to the point where it could be passed on to industry,” Clydesdale explains. “Much to my chagrin, they decided to call it the [Fergus M.] Clydesdale Center for Foods for Health and Wellness. I was very interested in having a different name.”

The issues the center plans to address are myriad and include determining the bioactive components in foods and increasing their bioavailability, detecting the anti-inflammatory effects of various foods and food constituents, and determining the cancer-inhibition effects of certain foods. “We’ll also be looking at things in the marketplace to make sure that they’re safe and effective not only for microbiological reasons but also for metabolic reasons. We’ll be doing all kinds of work on … the microbiome,” Clydesdale reveals. “The purpose is to create a level of knowledge and bring that level of knowledge up to the point that we can pass this knowledge off to industry, [which] can then put it into practice.” In addition to focusing on chronic diseases prevalent in the United States, the center is working on remedies to food issues around the world such as food security, malnutrition, and food safety. “We can [help] solve some of these terrible problems we have in Sub-Sahara Africa and other parts of the world where people are dying of malnutrition and starvation. The problems they have with not only malnutrition and not enough calories but also food safety are just incredible, [and] the liver disease they have from aflatoxins is just very scary,” Clydesdale points out.

Despite his transformational views on food science, a distinguished career, and numerous awards, Clydesdale is humble; he bestows his praise on the work and accomplishments of the food science faculty at UMass Amherst and at other universities around the country. “We like to think that the science we do is outstanding, but there is [also] outstanding science done elsewhere. Our work along with the really outstanding work of all the universities in this country … will have a huge impact on reducing the incidence of chronic disease. We’re not going to have a huge impact all by ourselves, [but] we’re most fortunate in having the center because we’re focusing on bringing areas together, which many places don’t do,” he proclaims. UMass Amherst and the Clydesdale Center have strategic research alliances with Cargill, ConAgra Foods, General Mills, Kraft Heinz Co., Mars Inc., and other food companies and work with local farms and small businesses.

Despite his transformational views on food science, a distinguished career, and numerous awards, Clydesdale is humble; he bestows his praise on the work and accomplishments of the food science faculty at UMass Amherst and at other universities around the country. “We like to think that the science we do is outstanding, but there is [also] outstanding science done elsewhere. Our work along with the really outstanding work of all the universities in this country … will have a huge impact on reducing the incidence of chronic disease. We’re not going to have a huge impact all by ourselves, [but] we’re most fortunate in having the center because we’re focusing on bringing areas together, which many places don’t do,” he proclaims. UMass Amherst and the Clydesdale Center have strategic research alliances with Cargill, ConAgra Foods, General Mills, Kraft Heinz Co., Mars Inc., and other food companies and work with local farms and small businesses.

“Our priority is doing excellent science to help as many people as we can,” Clydesdale says. “That’s why I went into this: because I saw a science where you could do really interesting work and the effects of that work had the potential of affecting a lot of humanity in your lifetime.” To those who criticize food science and the food industry, Clydesdale offers the following: “Food science has evolved over time to be much broader and multidisciplinary, and it is still evolving. [It] is the answer—and the only answer—to have a significant effect on feeding the world and attacking chronic disease and making the world healthier in the next 30 to 40 years.” How can anyone find fault with that?

For Health and Wellness, What Do Our Guts Tell Us?

For Health and Wellness, What Do Our Guts Tell Us?

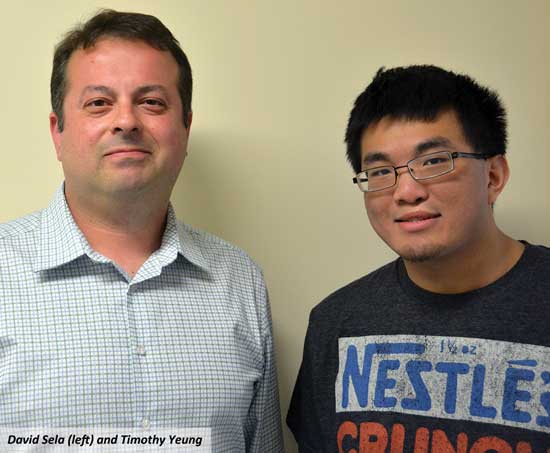

An integral part of the strategy to improve health and combat disease at the Fergus M. Clydesdale Center for Foods for Health and Wellness is unraveling the secrets of the human microbiome, particularly gut microbiota. The primary faculty member responsible for deciphering the genomic behavior of microbes in the microbiome is assistant professor David Sela. “The human microbiome refers to the collection of microorganisms that live in and on us,” Sela explains. Estimates of how many microorganisms are living in and on us vary, but the consensus is that it is a huge number: approximately 1013 or 100 trillion microbial cells—that’s three times more microbial cells than human cells. Humans acquire these microbes mostly from encounters with other humans (for example, traveling through the mother’s birth canal and ingesting breast milk). They are also incredibly diverse: The human genome contains about 20,000 genes, but for every human gene, there may be as many as 300 microbial genes. The microbes in the gastrointestinal tract form the most dense and diverse microbial community in the human body. Research on gut microbes constitute the bulk of the work in Sela’s laboratory.

One area of study for Sela and his research team is probiotics, which are live microorganisms that support digestive health. “What I think probiotics do—and I could be wrong—is influence the transcription or gene expression of the [microbes] already living within one’s gut. So they may not necessarily colonize [the human gut],” Sela posits. Moreover, it is likely that many of the probiotics in certain functional foods are ineffective. Timothy Yeung, a graduate student in Sela’s laboratory, explains: “For most of the fermented dairy products that incorporate probiotic cells, they’re in a free form. Because of this, they’re exposed to adverse effects in the digestive tract that could cause degradation of the cells. This causes a majority of the [probiotic] cells to die off on their way to the colon, which is where they might … contribute to the microbiota in some way.” In collaboration with professor Julian McClements’s laboratory, Yeung developed a way to encapsulate probiotic cells in a protective food-grade coating (alginate and chitosan) that allows probiotics to remain viable during storage and gastrointestinal transit.

Research on the microbiome and gut microbiota is still in its infancy. Thus, “not everything in the human microbiome is completely understood, and that’s the exciting part: there’s stuff out there to discover,” Sela says. While specifics are not yet clear, what is clear is that the effects of the microbiome on the human host are multifaceted and largely beneficial.

Toni Tarver is senior writer/editor of Food Technology magazine ([email protected]).