Toasting Ingredients in Fermented and Distilled Beverages

INGREDIENTS

They’ve been both revered and reviled throughout history, produced by many of our country’s founding fathers and later prohibited by way of a Constitutional Amendment. The popularity of beer, wine, and distilled spirits is seen around the world, as these beverages play roles in people’s enjoyment, culture, economy, and rituals.

They’ve been both revered and reviled throughout history, produced by many of our country’s founding fathers and later prohibited by way of a Constitutional Amendment. The popularity of beer, wine, and distilled spirits is seen around the world, as these beverages play roles in people’s enjoyment, culture, economy, and rituals.

At one time people would simply ferment fruit or wet grain in clay and wood pots to produce wine- or beer-like beverages. Today, modern equipment and myriad ingredients produce a diverse range of fermented and distilled beverages to suit every taste. These ingredients—cultured yeast, dozens of grains, and different hops varieties along with flavorings and extracts, spices and herbs, and enzymes—have specific functions that help manufacturers innovate in the beer, wine, and spirits category.

What’s Inside That Bottle of Beer?

Malt is a major contributor of flavor, aroma, color, and body of beer. When you taste and smell nutty, burnt, sweet, or caramel notes in beer and notice the range of colors of beer from golden yellow to amber to black, you have malt to thank. The brewing grain of choice is barley because it contains large amounts of starch that can be converted into sugar, is light in color, is neutral in flavor, and has plenty of enzymes that break down starches and proteins. Barley is most commonly used, but grains like wheat and rye add flavors, creamy texture, and head retention to beer while corn and rice lighten the body and flavor of beer (and the cost), particularly industrial lagers (Mosher 2009). Oats smooth out the body and add a silky texture to oatmeal stouts.

Barley is steeped, sprouted, and kiln-dried in a process called malting to release enzymes that convert some of the starches into sugars that the yeast will later use to ferment the beer. The drying process helps color to develop. In addition to being dried, the malt can be roasted or smoked to create more layers of flavor and to darken the color.

There are several types of malts based on how they are dried/roasted. Briess Malt & Ingredients, Chilton, Wis. (brewingwithbriess.com), produces a comprehensive range to brew everything from pale-yellow pilsners to inky black stouts. Its kilned base malts produce beers that are the lightest in color and have a sweet, mild to malty taste. Next are high-temperature kilned malts, which produce beers that are a bit darker with light to intense malty and biscuit flavors and aromas. Roasted caramel malts give beer a light tan color and toffee and burnt sugar flavors that are similar to caramel. The company’s specially processed malts produce beers in amber shades with flavor notes of biscuit, toast, nuts, wood, raisins, or prunes. Finally, there are malts that produce the darkest, most intensely flavored beers. Roasted barley made from raw barley produces bitter flavors and coffee flavors and aromas while dark roasted malts produce roasted coffee and cocoa notes. One of the company’s newest ingredients is Caramel Rye Malt, which has caramel and bread crust flavors and spiciness from the rye grain and produces beers in colors ranging from burnt orange to brown. For additional depth of flavor, the malt can be used with the company’s Rye Malt or Rye Flakes.

Liquid and dried malt extracts are used to improve body and head retention, adjust color, provide a rich malty flavor, and provide fermentable sugars. Depending on the malt used to make the extracts, the flavor, color, and enzymes levels can differ. Cedarex liquid malt extracts from Muntons Malt, Stowmarket, United Kingdom (muntonsmalt.com, muntonsmicrobrewing.com), are used as a straight malt replacement or to extend the brew when added to a conventional mash. The company also offers liquid malt extracts made from colored malts to produce darker bases.

Next up, hops are added to the wort (a starchy-sugary liquid resulting from heating malt and water). Hops are small, green cones covered with a papery coating and filled with compounds that give bitterness (alpha acids) and a range of aromas like fruit, spice, citrus, floral, pine, herb, and grass (essential oils) to beer. They also contain humulones and lupulones, which have antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects. A review study published in Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety points out the beneficial health potential of hops (Karabin et al. 2016).

Each variety of hops is different in the amount of bitterness compounds and types of essential oils. Bitter compounds called alpha acids are insoluble so they are added to the wort early on as the wort boils to release the bitter compounds. Hops can also be added in the middle and at the end of the boil as well as later in the brewing process to release flavor and aroma compounds. Hops are available in whole and pellet forms, the latter being more compact and easier to store.

Yeast are single-celled fungi responsible for converting sugar into ethyl alcohol, or ethanol, carbon dioxide, and very small amounts of other compounds (flavor and aroma compounds like esters, sulfur-containing compounds, diacetyl, and more) during fermentation. Most beer is made with yeast that come from two main species, ale yeast called Saccharomyces cerevisiae and lager yeast called S. pastorianus. Within these species are many different strains of yeast that can be characterized by the temperature ranges at which they ferment (generally lower for lager yeast and higher for ale yeast), the flavor and aroma compounds they help produce in beer, how well they convert sugar into alcohol (attenuation), whether they sink or stay afloat in the fermentation tank (flocculation), and how well they grow and multiply.

There are some styles of beer that require different yeast species and even bacteria (Lactobacillus and Pediococcus) to develop the flavor and aroma characteristics that these beers are known for (Mosher 2009). Brettanomyces is a wild yeast responsible for horsey and barnyard aromas in beer and is most commonly used in lambic-style beers, sour ales, gueuze beers, and Berliner weisse beers. Although Brettanomyces and other wild yeasts are considered contaminants, there are some brewers who embrace the funky flavors and aromas they contribute.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

“A wild yeast is often described as any strain that is different from the cultured yeast intended to be used in the process of making beer,” says John Maier, brewmaster at Rogue Ales, Newport, Ore. (rogue.com). “While all yeast strains used in brewing contribute to the flavor and aroma of the final beer, ‘wild yeasts’ used in brewing contribute a characteristic funk that the brewer can use as a tool.”

Manufacturers of yeast strains for ales and lagers along with strains specifically for Belgian-style beers, wheat beers, wild-fermented beers, and sour beers often contribute to a more diverse offering of yeast by isolating new strains. White Labs, San Diego, Calif. (whitelabs.com), recently released WLP611 New Nordic Ale Yeast, a blend of three yeast strains (Torulaspora delbrueckii and two from S. cerevisiae) that ferments maltose and produces aromas that resemble Belgian saison and German hefeweizen beers. This yeast was developed under the company’s Yeast Vault Program, a collection of one-of-a-kind yeast strains, most of which, according to the company, have not been used in commercial products. The company also sells several different strains of wild yeast like Brettanomyces. Lallemand Brewing, Montreal, Canada (lallemandbrewing.com), supplies the brewing industry with dry brewing yeast, which it produces through a multi-step process to deliver a finished yeast ingredient that is less than 7% liquid. The company points out that dry yeast can be used in the primary fermentation or in bottle conditioning. Another yeast supplier, Wyeast Laboratories, Odell, Ore. (wyeastlab.com), specializes in producing liquid yeast cultures to commercial brewers and homebrewers. Liquid yeast differs from dry yeast in that more strains of yeast are available in liquid form than in dry form since many yeast strains do not survive the drying process, according to the company.

The same ingredients used to make beer for centuries—malt, hops, yeast, and water—continue to be the core ingredients that large-scale commercial (macrobreweries), craft, and home brewers use. The combination of these ingredients produce quite a variety of beers, but to make a product stand out, brewers, specifically craft brewers, are adding a whole range of other flavorful ingredients like herbs, spices, fruits, vegetables, nuts, coffee, chocolate, chilies, coconut, tree extracts, mushrooms, and oyster shells. Some craft brewers are even aging beer in spirits and wine barrels, neutral oak barrels, and in foeders (large wooden vats used to age wine), which are not ingredients in the traditional sense, but do release flavor and aroma compounds and tannins from the wood into the beer. Barrel aging also subjects the beer to other conditions that affect its properties. Barleywines are aged in charred oak barrels or even bourbon barrels, and Maier explains that the high amounts of malts and hops in barleywines results in a higher concentration of chemical compounds to react to oxygen levels and temperature factors during aging. “The amount of malts—and hops required to balance the sweetness—typically found in a barleywine dwarfs that found in other styles,” says Maier, who created the original recipe for Rogue’s Old Crustacean Barleywine. “Certain general effects occur over time, including an increase in sweet, toffee, and sherry notes. The biggest perceivable change occurring in the aging of beer is the interaction between reducing bitterness and increasing sweetness.” Most sour beers are aged in oak or wine barrels. Beers aged in bourbon barrels will have the strong and sweet boozy flavors of the spirit and a thick, almost syrup-like body. Bourbon barrel-aged brews are often stouts (though not all stouts are bourbon barrel-aged), and a cult following has formed around these brews as enterprising craft brewers release limited editions of specially formulated bourbon barrel-aged stouts.

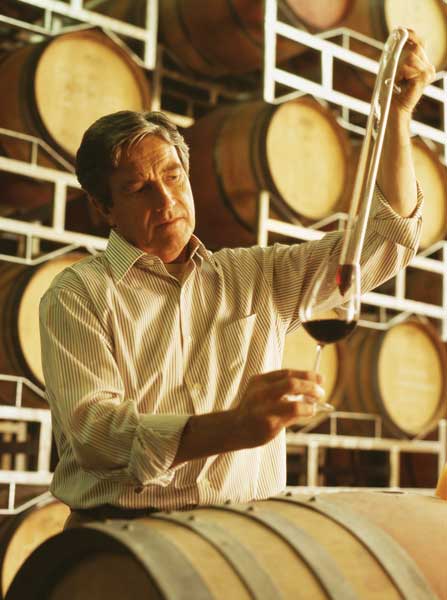

From Grapes to Wine

From Grapes to Wine

There are thousands of grape varieties, or cultivars, each able to make wine with different flavors, textures, sweetness, and astringency (about 1,300 varieties are used commercially to make wine) (Goode 2014). The grape berry used to make wine is, by weight, 75% pulp, 20% skin, and 5% seeds (MacNeil 2015). The sugar in the pulp is fermented into alcohol by yeast, which produce at least 400 of the estimated 1,000 volatile flavor compounds in wine (Goode 2014). The grape juice and skin contains tannins as well as chemicals like polyphenols and anthocyanins that contribute to the wine’s aroma, flavor, and color. Stems and seeds also contain tannins. External factors like climate, temperature swings, rainfall, the amount of sunlight, soil conditions, and elevation at which the vines grow affect the qualities of wine grapes and in turn the wine itself.

After the grapes are harvested, they go through a crusher-destemmer to press the juice and remove the stems. To make red wine, both the skins and juice are sent to the fermenter (some winemakers of certain red wines will leave the stems attached to the grapes or add stems to grapes in the fermenter). To make white wine, the juice is separated from the skins before being sent to the fermenter.

Different yeast strains exist in the air, in the vineyard, on surfaces in the wine cellar, and even on the grapes themselves. On their own, these yeasts can ferment the sugar in the grape juice into alcohol, and some winemakers are happy to follow this procedure. The challenge winemakers may face with letting these wild yeasts ferment the juice is that the fermentation may take too long, during which time undesirable flavors can form or spoilage bacteria can grow (MacNeil 2015). Many winemakers will use cultured yeasts available from yeast suppliers, which gives them control over the rate of fermentation and the ability to customize the flavor profiles of wine. Yeast strains can affect the speed and intensity of fermentation, which, in turn, can affect the flavor and aroma of the wine. The most common yeast strains used to ferment the grape juice are cultured strains of S. cerevisiae, but others species different from Saccharomyces such as T. delbrueckii and Metschnikowia pulcherrima have been isolated and developed to give winemakers a more diverse range of yeast options, according to Lallemand (lallemandwine.com). Fermentis, a business unit of Lesaffre, Marcq-en-Baroeul, France (fermentis.com), produces Safœno active dry yeast ingredients for winemaking with a specific focus on aroma and character development. The yeast strains are said to help develop particular fruit and floral (and other) flavor and aroma characteristics in a range of grape cultivars under different conditions (slow fermentation, secondary fermentation, in musts with high sulfur dioxide levels, and in fermentations that get “stuck”). Three yeast ingredients from Biorigin, Lençóis Paulista, Brazil (biorigin.net), each have a specific function in the production of wine like eliminating turbidity that protein instability causes during winemaking (Mannovin), and providing nutrients for fermentation (Goldcell CW yeast cell wall and Goldcell LIS XP inactive dry yeast).

In addition to yeast, winemakers can add any number of approved substances to wine, and they are not required to list them on the label. In the United States, the Code of Federal Regulations states that “Materials used in the process of filtering, clarifying, or purifying wine may remove cloudiness, precipitation, and undesirable odors and flavors, but the addition of any substance foreign to wine which changes the character of the wine, or the abstraction of ingredients which will change its character, to the extent inconsistent with good commercial practice, is not permitted on bonded wine premises” (CFR 2016). In general, these additives are used to create a more stable product, as wine is filled with plenty of volatile compounds, and to produce a more consistent product. The additives on the list are legally allowed to be used in wine and include sulfites to kill bacteria and undesirable yeast, enzymes to break down the cell walls in grape skins or modify the flavor and aroma of the wine, tannins for astringent taste, and acids that can affect the color, flavor, and texture of wine. Other allowable material includes ones that are classified as clarifiers and fining agents such as albumen, gelatin, and isinglass. These can help prevent haze in wine and attract small particles so that they can be strained away or fall to the bottom of the barrel.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Craft Hard Cider Emphasizes Tradition

Craft Hard Cider Emphasizes Tradition

When looking at craft beer menus, it’s likely you will see listings for hard cider. This beverage is having a moment of late, with manufacturers both small and large releasing their own versions of this age-old beverage. While you might see it sold next to beer on store shelves, don’t confuse the two. Simply put, hard cider is a fermented apple beverage. While additives like sulfites, colorings and flavorings, sugars, and acids can be added, the burgeoning craft cider movement is going back to basics with cider recipes.

Craft cider manufacturers view the apple much like winemakers view the grape. “Like wine, where you grow the apples contributes greatly to the character of the cider,” says Gregory Hall, founder and CEO of Virtue Cider, Fennville, Mich. (virtuecider.com). He adds that southwestern Michigan’s “cider coast” has a climate similar to European cider-producing regions in Normandy, France, Somerset, United Kingdom, and Asturias, Spain—areas conducive to growing apple varieties used in cider production.

The barrels in which the cider ages, too, give distinction to the beverage. “Each barrel, after many uses, becomes its own unique biosphere,” says Hall. “You put the same cider in 100 different barrels, each one creates a different cider, many slightly different, many distinctly unique. It gives our cider a level of complexity that can’t possibly be achieved with just fruit.”

The yeast strains used to produce cider also contribute to the development of interesting flavors and aromas. Certain strains of champagne yeast are commonly used, as are specialty strains. White Labs, San Diego, Calif. (whitelabs.com), developed a line of specialty strains from wild yeast and from combinations of wild yeast, ale yeast, or wine yeast specifically for use in cider production. Of course, some manufacturers leave the fermentation up to the wild yeast found on the apples and in and around the production facility. “Most of my friends in Normandy, Asturias, and [southwest] England ferment cider the old-fashioned way, naturally with the native yeast from the orchard,” says Hall. His approach is to use wild yeast found naturally in the apple orchard (“Wild yeast provide a level of complexity that one pure culture can never match.”) and add cultured yeast to most fermentation tanks, which affects flavor and aroma and can also encourage a more rapid fermentation of his cider varieties.

Beverages Produced By Distillation

Distilled spirits are born from the same process that gives us wine and beer, essentially a carbohydrate-rich mash that is fermented by yeast. After this, the fermented mash is run through a distillation process (alcohol is boiled out at 173°F and then condensed back to liquid form, sometimes multiple times). The distillate is filtered and then, depending on the type of spirit, is either bottled or aged in barrels or casks before bottling.

There are several categories of spirits, each defined by the carbohydrate source from which it is distilled (i.e., grain for whiskey and gin; pale grain or vegetables like potato or beet for vodka; fruit juice/pulp for brandy; sugarcane juice and molasses for rum; and agave plant for tequila). Each category can be broken down further, giving distinctions between the different types of whiskeys or types of rum, for instance.

Grain manufacturers like Briess feature distiller’s malts (pale, smoked, caramel, and specialty) with high alpha amylase and diastatic power amounts to increase fermentable yield, as well as high-yield flours, raw grains, and flakes. Fermentis, a business unit of Lesaffre, offers yeast strains specific for the production of whiskey, bourbon, spirits distilled from fruit, and spirits that have neutral flavor and aroma.

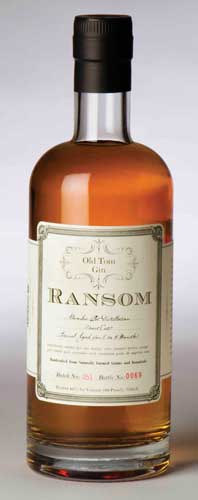

Other ingredients are added along the way. Gin is made with juniper berries and botanicals. Neutral spirits are typically used as a base for flavored alcoholic beverages and cream-based alcoholic beverages to which distillers add sugar, coloring agents, and ingredients to add flavor. Flavored vodka is a trend now, as is creating spirits with citrus peel, herbs, chili peppers, and other ingredients. Wood like cherry wood and nuts like walnuts are not unheard of either, and Tad Seestedt, the proprietor of Ransom Spirits, Sheridan, Ore. (ransomspirits.com), says that ingredients like bark, nuts, herbs, and more add great flavor complexity to spirits such as the company’s vermouth.

Other ingredients are added along the way. Gin is made with juniper berries and botanicals. Neutral spirits are typically used as a base for flavored alcoholic beverages and cream-based alcoholic beverages to which distillers add sugar, coloring agents, and ingredients to add flavor. Flavored vodka is a trend now, as is creating spirits with citrus peel, herbs, chili peppers, and other ingredients. Wood like cherry wood and nuts like walnuts are not unheard of either, and Tad Seestedt, the proprietor of Ransom Spirits, Sheridan, Ore. (ransomspirits.com), says that ingredients like bark, nuts, herbs, and more add great flavor complexity to spirits such as the company’s vermouth.

Seestedt and others are part of a growing craft distillery movement across the country. Producing distilled spirits on a smaller scale allows the craft distillers to experiment with different methods of distilling, use local or organic ingredients, or get creative with their recipe development. Oftentimes, they grow their own ingredient or malt their own grains, or they use stills and other equipment that is custom-made. Seestedt has embraced this wholeheartedly by employing the use of direct-fire distillation (“an original, traditional method of distilling,” he says), growing as many ingredients on the property as possible, not using extracts in the beverages, and generally practicing quality over quantity.

Fermented and distilled beverages are very diverse categories of beverages that boast products that come in ranges of flavor and style varieties, thanks in part to innovations in the ingredients used to produce them and to manufacturers developing creative product offerings. The craft beer and distilling movement is driving innovation in the beer and spirits markets, while health-minded consumers are enjoying tart and tangy kefir beverages and flavor-focused kombucha drinks. And, of course, wine will continue to be enjoyed as winemakers experiment with different types of yeast strains, grape varieties, and more.

Next month’s Ingredients section will provide a preview of some of the ingredient suppliers exhibiting at IFT16 in Chicago, July 17–19.--- PAGE BREAK ---

Old Recipe Inspires New Beer

Old Recipe Inspires New Beer

Research conducted on the Wari people, who once lived in Cerro Baúl in southern Peru, led to an interesting discovery by researchers from The Field Museum located in Chicago. Ceramic artifacts from a brewery that dates between 600 and 1050 AD contained residues of maize and molle berries (pink peppercorns), suggesting that the Wari people combined the two to make a brew that was stronger and more flavorful than the traditional corn beer called chicha that the people drank. This inspired the creation of WARI Chicha de Molle Inspired Ale, a beer made with purple corn and molle berries. The researchers collaborated with the brewers at Off Color Brewing, Chicago (offcolorbrewing.com), to develop the beer, which according to the brewery, has “dry, grainy funk and pepper spiciness.” Another interesting quality of the beer is its color: purple with pink foam lacing. The limited-edition beer is sold at the museum on tap and in bottles.

Alcoholic Beverages as Culinary Tools

Cooking with alcohol is nothing new. Wine is used to make pan sauces, rum and bourbon add flavor to cake, and beer complements other ingredients in chili and sauces. Thanks to ingredients like denatured spirits, wine reductions, and traditional flavorings (both natural and artificial forms), consumers now find a diverse range of alcoholic beverage–flavored food products and culinary applications—everything from merlot-flavored candy and bourbon-flavored barbecue sauce to ale-flavored seasoning blends and stout-flavored cake frosting.

• Denatured spirits from Mizkan Americas, Mount Prospect, Ill. (mizkan.com), include rum, tequila, brandy, whiskey, bourbon, and moonshine. The addition of a small amount of salt renders a spirit undrinkable (denaturing) so it is no longer subject to alcohol excise taxes. While denatured spirits are not suitable to drink, they are still flavorful additions to sauces, dressings, marinades, dips, frozen and refrigerated entrees, meat applications, flavors, and bakery. Mizkan includes its Porter Ale in its denatured spirits line of ingredients, and featured it in Belgian Ale, Stout Beer, and Blue Moon Ale Type Barbeque Sauce product concepts at the Research Chefs Association (RCA) 2016 Annual Conference & Culinology Expo. With a taste like a combination of stout and pale ale, the Porter Ale ingredient enhances food with notes of brown malt, coffee, and chocolate. The company also manufactures a line of wine reductions in burgundy, Chablis, sweet Marsala, red port, and sherry versions using a time-and-temperature-controlled process without salt or added sugar. These ingredients can be added at the beginning or the end of the cooking process to blend the wine flavor with the flavors of the other ingredients used in the formulation or at the end to create a stronger lingering of the wine flavor. Use wine reductions in the same applications as denatured spirits as well as in confections and ice cream.

• Bell Flavors & Fragrances, Northbrook, Ill. (bellff.com), featured some trendy alcohol flavors in product concepts inspired by Cuban cuisine and with a Colorado twist at the RCA event held in Denver. A Pineapple Mint Mojito Sidecar product concept was formulated with the company’s Rum Flavor while pickles used on a Cuban sandwich were flavored with Amber Ale Flavor that lent toasted malt characters and a light fruity flavor reminiscent of a favorite beer style in the Colorado craft beer scene. The company also offers other craft beer flavors (IPA, Belgian Style Ale, American Style Lager, Hefeweizen, and Stout) and Hard Cider Flavor.

• Barrel aging is common practice in the wine industry and in the production of many distilled spirits. The beverages aged in wood barrels take on some of the flavor and aroma compounds like vanillin and tannins found in the wood used to make the barrel. Manufacturers can add barrel-aged flavors to flavored vodkas, cordials, and liqueurs, and nonalcoholic applications like ice cream, confections, meat, cheese, and dressings with Barrel Aged Flavors from David Michael, Philadelphia (dmflavors.com). The liquid, natural WONF flavors come in cherrywood, applewood, oak, maple, hickory, and mesquite versions.

• Try one of the six alcoholic beverage flavors from Sensient Flavors, Hoffman Estates, Ill. (sensientflavors.com), to add layers of flavor to any number of food products. Natural Red Wine Reduction has fruity and floral notes, and Natural Margarita-Type Flavor has woody flavor notes with a touch of orange peel and lime. Two other flavors capture characteristic flavor notes of classic spirits. Natural Brandy Flavor has woody, caramel, and vanilla notes with a slight fruity aroma while Natural Kentucky Bourbon-Type Flavor has the resin and char notes of the barrel with woody, caramel, and sweet notes. Finally, Natural IPA Beer-Type Flavor has an expected hoppy flavor with a slight yeasty character and fruit and floral notes, and Natural Stout Beer-Type Flavor has dark rich notes of yeast-risen bread and chocolate notes.

Enzymes for Fermented Applications

Enzymes are naturally present in malt and yeast and are crucial in the malting, mashing, and fermentation processes. Some brewers, especially large-scale ones, will supplement with commercial enzyme preparations to maintain consistency, reduce costs, and optimize processes across production lines. Wine makers, too, may choose to use enzymes to speed up reactions at various steps in the winemaking process and to help develop flavors and aromas in wines.

Biocatalysts, Cardiff, Wales, United Kingdom (biocatalysts.com), offers enzymes for brewing that hydrolyze starches and ones that break down non-starch polysaccharides. Its pectinase enzymes for winemaking decrease the viscosity of must for increased juice extraction. Alphalase Advance 4000, a new brewing enzyme from DuPont Nutrition & Health, New Century, Kan. (danisco.com/food-beverages), can reduce or completely eliminate diacetyl, which can cause undesirable off-flavors. In addition to a line of enzymes for use in the various stages of beer and spirits production, Enzyme Development, New York (enzymedevelopment.com), also focuses on wine production with its Enzeco enzymes to remove unwanted fermentation byproducts and increase grape juice yield. Enzyme Innovation, Chino, Calif. (enzymeinnovation.com), offers enzymes that provide functions like increased extraction, flavor control, and stability in beer and enzymes that improve organoleptic characteristics of wines and clarification and filtration in wine. Enzymes from Novozymes, Bagsværd, Denmark (novozymes.com), address cost-effective cooking of cereal grains, optimizing raw material use, wort separation and beer filtration, attenuation control, and fermentation control.

Kefir and Kombucha Find Their Niche

While kefir and kombucha are made differently from the other fermented beverages discussed in this article and contain small amounts of alcohol (kombucha) or no alcohol, they have piqued the interest of consumers and product developers lately.

Both beverages appeal to health-conscious consumers mainly because of their probiotic content. In recent years, news about the health benefits of probiotics has led to the development of a range of probiotic-containing food products like kefir, a fermented milk product with a tart/tangy taste, and kombucha, a fermented tea that is slightly effervescent. Manufacturers of probiotic cultures have developed strains specifically for use in these beverages. Chr. Hansen, Hørsholm, Denmark (chr-hansen.com), and DSM, Heerlen, the Netherlands (dsm.com), for instance offer probiotic cultures (eXact Kefir and DelvoFresh, respectively) for dairy products like kefir that promise to deliver the health-promoting benefits of probiotics without compromising the taste and texture of the kefir product.

While these beverage products seem more suited for health food stores, they have penetrated larger retail markets across the country. Lifeway Foods’s kefir products are widely available at the retail level, and there are even store brands available such as Trader Joe’s kefir products sold in its stores. Kombucha too has a retail presence, with stores like Target and Whole Foods selling several brands, as well as an online presence where small manufacturers have cultivated a growing businesses. The health halo of the beverages appeals to consumers, and so does the flavor variety. Certain fruit flavors pair well with creamy dairy—strawberry, black cherry, peach, or blueberry in yogurt—so it is no surprise that the kefir products on the market boast the same types of flavors. Kombucha Wonder Drink manufactures kombucha with ingredients like rose petals, green cardamom, schizandra berries, goji berries, black pepper, and miso. GT’s Third Eye Chai Classic Organic Raw Kombucha from Millennium Products is blended with chai spices.

Tree Extract Stabilizes Foam

To produce a long-lasting, stabilized foam on beer, Ingredion, Westchester, Ill. (ingredion.us), offers FOAMATION QB DRY foaming agent. The ingredient is derived from the Quillaja saponaria Molina tree, more commonly called the soapbark tree, a source of foam-inducing compounds called saponins. These surfactants “inherently have high surface active components which stabilize the water and air, creating an interface of bubbles that in turn, stabilize the foam,” says Dinah Diaz, senior marketing manager at Ingredion. The company standardizes the active saponin component when producing the FOAMATION QB DRY foaming agent, she adds, to ensure consistent performance and functionality in beverage applications. “Beer manufacturers, whether large or small, often see the value in removing chemical-sounding ingredients from their products and replacing them with our naturally derived foaming extracts,” says Diaz. Ingredion’s foaming agent ingredient not only functions in beer, producing thick, long-lasting foam and improving frothy lacing in beer, but in other alcoholic beverages where foam is desired. “In frozen alcoholic beverages FOAMATION QB DRY foaming agent improves the ice crystal texture, creating a smoother mouthfeel due to its entrapment of air,” says Diaz. “It also increases overrun by over 80%, creating cost savings for manufacturers.”

www.ift.org

Members Only: Read more about ingredients that are used to formulate fermented and distilled beverages at ift.org. Type the keywords into the search box at the upper right side of the home page.

Karen Nachay,

Karen Nachay,

Senior Associate Editor

[email protected]

References

CFR. 2016. Materials Authorized for the Treatment of Wine and Juice. Code of Federal Regulations, 27 CFR part 24.

Goode, J. 2014. The Science of Wine: From Vine to Glass, 2nd ed. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Karabin, M., T. Hudcová, L. Jelinek, and P. Dostálek. 2016. “Biologically Active Compounds from Hops and Prospects for Their Use.” Comprehensive Rev. Food Sci. Food Safety, 15: 542–567.

MacNeil, K. 2015. The Wine Bible, 2nd ed. New York: Workman Publishing.

Mosher, R. 2009. Tasting Beer: An Insider’s Guide to the World’s Greatest Drink. North Adams, Mass.: Storey Publishing.