Applying Good Science to Create Great Recipes

CULINARY POINT OF VIEW

A cast member of the television show America’s Test Kitchen (ATK), Chef Dan Souza is executive editor of Cook’s Science—a new digital experiment with cooks, scientists, and journalists reporting from the world of food and science. He, along with Molly Birnbaum, co-executive editor and food journalist, are delving into the science behind ice cream, tortillas, palate cleansers, and more.

Q: Dan you have a background in communications before attending culinary school, and Molly you are a successful food writer. How did you guys come to work for America’s Test Kitchen?

Dan Souza: I worked in advertising for a while and realized that my passion was definitely much more in the kitchen. So after working for a little bit at Restaurant Dante in Cambridge, I enrolled in culinary school at the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, N.Y. It was a two-year program, and while I was there I learned a ton. I also had a lot of questions about why we were doing certain things.

I worked in Manhattan for a little bit after graduating and knew that I wanted to do something in food, wanted it to be cooking, but wanted the opportunity to spend a little more time working on my recipes and diving into some of the “whys” in cooking. That eventually led me to America’s Test Kitchen. I got here in 2008, and I really saw the beauty in using the scientific method to uncover interesting techniques or new ways to approach recipes. It’s a really good job for problem solving. You run into various issues every day that you get to try and come up with good solutions for.

Cook’s Science brings together a lot of different ideas that Molly and I are really passionate about. There’s the storytelling that comes from Molly’s journalism background, the science—we’re both just science geeks, and then, obviously, there’s the cooking.

Molly Birnbaum: I have been really into cooking for a very long time and I wanted to be a chef. I studied art history in college, but after I graduated I started working in restaurants immediately trying to work my way up from the bottom and learning as much as I could. I was actually supposed to go to the Culinary Institute of America, but I didn’t make it because I was in a car accident in which I lost my sense of smell due to a head injury. As you probably know, smell is a huge part of flavor and so without it I couldn’t proceed.

I knew that I couldn’t cook, but I had been writing a blog—this was around 2005—about cooking and working in restaurants and I loved that so as soon as I recovered from the accident I thought “Why not try and write?” So, I moved to New York City and started interning at various magazines, eventually went to grad school, and moved into the world of journalism from there.

I got to America’s Test Kitchen because I had just finished writing a book about my experience with smell, which was a reported memoir about the science of smell and flavor and how it affected eating and cooking, in addition to lots of other aspects of my life. The book hadn’t come out yet but I really needed a job. I sort of stumbled into this job because our creative director, Jeff Bishop, was looking for help with what became the first science book that we published here in America’s Test Kitchen called “The Science of Good Cooking,” which came out in 2012. That’s where I met Dan because he was also working on the book.

Q: How did the idea for Cook’s Science develop? What does it bring to the ATK family of brands that may have been missing before?

Souza: First and foremost we’re doing a lot of things the same. There’s a real core to America’s Test Kitchen with the use of the scientific method to make food taste great. But one of the biggest differences is that we are looking totally outside of the Test Kitchen, chasing after stories, and through that learning, we are improving our recipes, techniques, and our understanding of the science of food.

Birnbaum: We are really aiming to add storytelling on top of these scientifically-developed, foolproof recipes. The stories involve people, places, and things that are happening in the world that—if you are interested in good recipes and how they work—you will probably be interested in what these people are doing, what they’re learning, and then, ultimately, what we take away from those experiences and distill in the Test Kitchen.

Q: How do you take extremely science-heavy information—such as in Penn State’s ice cream science course—and make it accessible for the non-food scientist?

Souza: Having a science expert on staff is really important so that we can have conversations about it. Plus, we have a lot of scientifically-minded folks on our team who come from really different backgrounds. So, we work and talk together a lot and through that we come up with better ways to describe processes and techniques. Another aspect of it is how we visualize things—whether it’s in video or photography and illustrations in order to try to get them to become super recognizable for people.

Birnbaum: I also think that a big part of our job here at Cook’s Science is translating from scientists. So, talking to people who are working in the highest levels of science—such as the dairy scientists at Penn State—and asking them enough in-depth questions to understand the information in a way that we can relate. We’re learning how to translate science for the layperson.

Q: Cook’s Science works extremely well as a digital product. You use videos and annotations in an effective way to help clarify and entertain. Are there any plans, beside the cookbook, to expand beyond digital? Perhaps a television show?

Birnbaum: I think it’s something on our minds for sure. Possibly down the road. We love doing the videos and we think it’s such a great way of talking about the science and showing recipes and food so I think it would be a really great fit for us down the line.

Souza: Nothing is off the table in terms of what we might do with Cook’s Science, but we’re really happy to be serving content digitally with our website. It gives us a lot of flexibility in what we publish.

Q: Science plays a huge role in this new endeavor. Oftentimes people can hear “science” and “food” in the same sentence and become hesitant and fearful. Is it your mission to make science less intimidating for people?

Birnbaum: I think that that is 100% the way people feel on a gut level if they haven’t studied science or it’s not something they’ve been interested in. It can seem scary and obtuse and hard to understand, making food way more complicated than anyone wants it to be.

I think what we try really hard to do at Cook’s Science is make it attainable for the layperson and really put it in terms of stories. So it’s not capital “S” science—equations and getting deep into the nitty gritty stuff—it’s really about getting a big, important concept that relates to food that you eat every day. And by reading stories about it you’ll better understand the food and be more interested in the recipes that we’re publishing and that you’re making at home.

Q: You have already covered emulsions and nixtamalization. What are some other food science concepts you will be covering?

Birnbaum: I am working on a story about how sound affects flavor and our perception of flavor. So, it’s about what happens when you listen—either listening while you’re cooking or while you’re chewing. Or, what is going on around you auditorily when you are having dinner, whether that be music in a restaurant or noise on an airplane. It turns out that in each of those situations sound affects your perception of flavor pretty intensely and in really interesting ways.

Souza:: Another idea that we’re currently working on recipes for is using koji which is a fungus traditionally used for making miso, soy sauce, and sake. We have a story coming out about how American chefs are putting it to use on some really different foods like meats and grains, with some pretty cool results. So we are incubating and growing some really funky foods in the Test Kitchen right now.

Q:What is the editorial process like? How do you decide what you are going to cover next?

Birnbaum: So, our editorial process is that we meet with our team every week. We’re a small team—there’s five of us—but we talk about what stories we’re interested in as a team. What’s so great about our team is that we’re all interested in slightly different areas of food and food science. Everyone comes to the table with really interesting, different ideas.

We also take freelance pitches from journalists. That’s where the koji story came from. We’re really interested in hearing from people out there in the world who are interested in subjects or reporting on different things. We’re also interested in hearing from scientists. So much of what we do is talk to people out in the world so we’re constantly getting idea. Then we come together as a team and decide what we want to go for.

Currently, we are publishing weekly. We will be publishing more starting next year so we’re working on a bunch of different things all at the same time constantly.

Q:: You just released a “Cook’s Science” cookbook this month. What can we expect to see?

Q:: You just released a “Cook’s Science” cookbook this month. What can we expect to see?

Birnbaum: It’s modeled in a very similar way to the first book [“The Science of Good Cooking”]. Except instead of 50 different techniques and the science behind them, it’s 50 of our favorite ingredients and the science of how to make them taste their best and unlock their flavors. It’s ingredients that range from olive oil to tomatoes, pork butt to almonds and wine. It’s a wide range of ingredients and each chapter—like in the first book—has an essay getting into the science behind how they work.

Dan did an experiment for each chapter, which, like in the first book, are super information packed but also a lot of fun. We had a lot of fun finding new ways to show cool things about each one of these ingredients. The new thing about this book, besides the content, is that we have full-page color illustrations that help people to really understand how each of these different ingredients work. And, of course, there’s the recipes.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

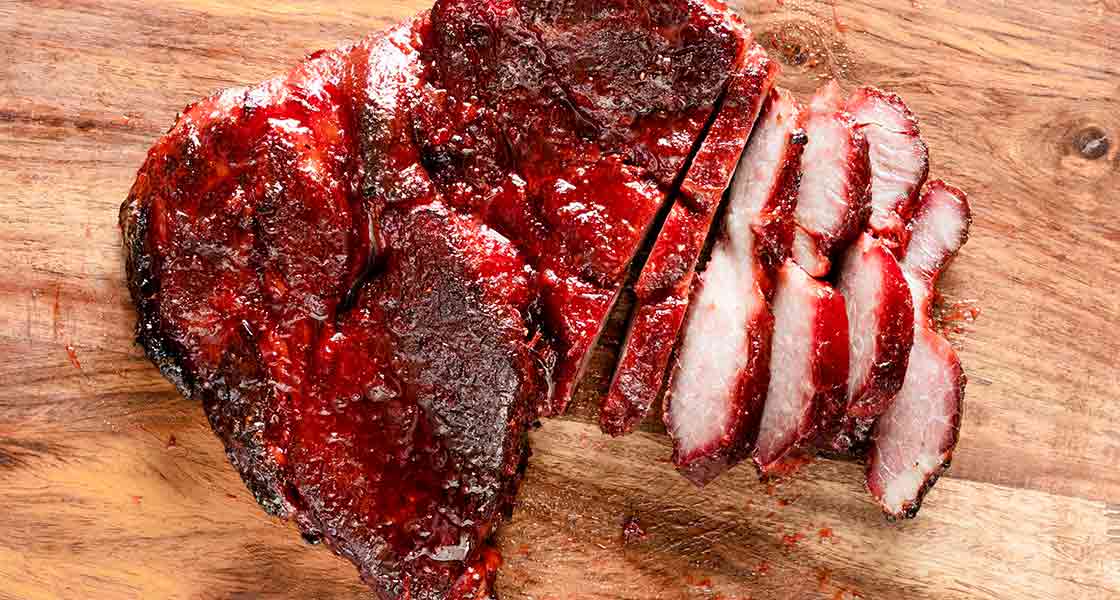

Chinese Barbecue Pork (Char Siu)

Ingredients:

- 4 pounds boneless pork butt

- 1 cup soy sauce

- 1 cup (7 ounces) sugar

- ¾ cup hoisin sauce

- ½ cup Shaoxing Chinese rice wine

- ¼ cup grated fresh ginger

- 2 tbsp toasted sesame oil

- 4 garlic cloves, minced

- 1 tbsp red food coloring

- 2 tsp five-spice powder

- ½ tsp ground white pepper

- ⅛ tsp pink curing salt

- ¾ cup honey

Method:

- Cut pork into four pieces and butterfly to create ¾-inch-thick pieces. Divide pork between two, 1-gallon zipper-lock bags. Whisk soy sauce, sugar, hoisin, Shaoxing, ginger, sesame oil, garlic, food coloring, five-spice powder, and pepper together in large bowl. Measure out 1 cup marinade and set aside. Whisk pink curing salt into remaining marinade; divide equally between bags and rub to distribute evenly over pork. Press out as much air as possible from bags and seal; refrigerate pork for at least 10 hours or up to 16 hours.

- While pork marinates, whisk honey and reserved marinade together in medium saucepan. Cook over medium heat, stirring frequently, until glaze is reduced to 1 cup, 4 to 6 minutes. (Glaze can be prepared up to this point and refrigerated for up to 2 days.)

- Adjust oven rack to middle position and heat oven to 250°F/121°C. Line rimmed baking sheet with aluminum foil and set wire rack in sheet. Spray rack with vegetable oil spray.

- Remove pork from marinade, letting excess drip off, and place on prepared rack. Cover sheet tightly with aluminum foil, crimping edges to seal. Bake until pork registers 195°F/90.5°C, 2 to 2½ hours. Remove pork from oven and discard foil. Let pork rest on rack for 30 minutes.

- Heat broiler. Brush both sides of pork with half of remaining glaze; broil until top is mahogany, 2 to 6 minutes. Flip pork and broil until second side is mahogany, 2 to 6 minutes. Brush both sides with remaining glaze and continue to broil until top is dark mahogany and lightly charred, 2 to 6 minutes longer (second side does not get broiled again). Transfer pork to carving board, charred side up, and let rest for 10 minutes. Slice pork crosswise into ½-inch-thick strips and serve.