Using Culinary to Showcase Ingredients

CULINARY POINT OF VIEW

After working as a chef in Las Vegas, Jeffrey Barish decided to pursue a degree in food science initially for the purpose of returning to the kitchen armed with the science to make him a better chef. Instead, he went on to get his PhD in food science. Now, as application scientist and R&D chef at Gold Coast Ingredients, Barish’s responsibilities include creating prototypes that highlight the company’s flavors. Here, we talk to him about the savory ice creams he developed for sampling at their booth at the IFT16 food expo.

Q: What led you to study culinary arts?

Jeffrey Barish: It’s going to sound a little cliché, but what led me to culinary arts was my love for food. As a child, my mom and grandparents were very good cooks and my grandfather was an avid gardener. Also, I grew up in San Diego, so we had fruit trees in my backyard. Food was always a really big part of my life. Once I got old enough, I wanted to help my grandparents and my mom cook dinner. Then as a got older I began cooking for my friends and I was always helping my parents cook. After graduating high school, I went to the Culinary Institute of America in upstate New York and that’s how it all started for me.

Q: You worked for seven years as a chef in Las Vegas before starting a BS in food science. What was the impetus for that move?

Barish: I’ve never lost my love for restaurants and I miss working in the restaurant every single day. The one and only reason why I decided to leave the kitchen was to become a better chef. I wanted to learn more about food science not because I wanted to be a food scientist, but because I wanted to understand what was happening in the kitchen.

For example, you one day you sear a filet and it forms the most beautiful brown crust but then the next day it gets gray and it doesn’t brown very well. Or, you make a hollandaise sauce and it comes out creamy and smooth, and four hours later it is just as beautiful and emulsified. Then you make it the next day and it looks great right but 30 minutes later it separates and turns into scrambled eggs and clarified butter. If you’re just chef and you don’t understand the physics or the mechanics that are behind what you’re actually doing, you may just disregard it and tell yourself “Oh it broke.” But you never ask yourself, “Why did it break? Or, why did the meat not brown?”

I was working in the kitchens at the time that molecular gastronomy became huge—around 2006 or 2007. I started to take notice, not because I wanted to become a molecular gastronomy chef, but because I realized that there are scientific answers to every single question I ever had in the kitchen.

My decision to leave the kitchen was a very hard one. My initial goal was just to go to the University of Massachusetts to get a bachelor’s in food science and then come back to the restaurant industry and use my knowledge to become a better chef. But different opportunities arose that led me pursue my masters and then my PhD.

Q: What does the job of an application scientist/R&D chef entail?

Barish: The easiest way to explain it is that my job sits in the middle of a triangle. One point of the triangle involves doing application work for customers that come to us with specific projects. So a lot of times I’ll be testing flavors in the matrix or in the system that the customer brings to us. I would say the majority of my time is spent on those type of projects.

The second part of my job is internal testing. For example, we are developing an all-natural red color that’s stable when baked. The flavorists and color chemists need my help to apply it because they can’t see what the color is until it’s baked in the actual cupcake.

And the third part of my job involves preparing for the trade shows we attend, such as IFT16. This is where I am given ultimate freedom in creating the prototypes we showcase. The only constraint is that flavors I use have to be natural.

Q: You developed the ice cream flavors that Gold Coast Ingredients featured at IFT16. Can you take me through the product development process?

Barish: The very first step was to choose a theme and a concept. Since IFT16 took place in Chicago in the summer, ice cream was an obvious choice so we could offer attendees something cold and refreshing. The concept of savory ice creams came about when our vice president of innovation told me that he had been seeing savory featured at a lot of trade shows recently.

The next step for me was to think about things that I like to eat—specifically, my favorite savory dishes. Then I had to decide whether that dish would translate into something sweet. So for example, there were two ideas that I explored that ended up getting cut. One was a shepherd’s pie ice cream, but the sweetness had no place in the dish. The other was a chicken enchilada ice cream. The sweet chicken ice cream worked well, which is why we used it for the chicken and waffles variety that was featured in the booth, but the red enchilada sauce and the cheese components just didn’t work. I initially came up with five different concepts and we moved forward with three: chicken and waffles, Thai coconut curry, and Japanese miso.

To take it from a concept to reality, I started by focusing on each one of the components in the concept dish. I made all the components—the sauces, ice creams, garnishes, and whipped creams separately, making sure each one tasted great on its own. Then I put everything together to make the actual ice cream sundae. At that point in the process I conducted tastings with the chemists I work with, and then the general manager, the lab manager, and even the owner of the company. I took everyone’s input and worked with the chemists to tweak certain flavors, did a couple of more tastings, and then we were ready for the event.

Q: Given your experience, what is one food science learning that you think chefs could benefit from?

Barish: I think it is the basics of food chemistry. I truly think that every single chef, regardless of where they work and what they’re doing, could benefit from understanding the very basic fundamentals of food chemistry—what an emulsion is; what the Maillard browning reaction is; what stabilizers are; how water activity works. These are fundamental concepts that if chefs knew more about them, they could accomplish so much more. It could really open up their minds to so many different things.

For example, they would understand the difference between the Maillard reaction, enzymatic browning, and caramelization. Those are three very different things that have a lot of science behind them. As a chef you may not understand the importance of patting down a piece of meat before you cook it, but knowing the science you would understand that Maillard reaction doesn’t occur if the water activity is above a certain level. A chef may just try turning up the heat, but if you start with a cold, wet piece of meat, it’s never going to brown. Chefs need to know the science behind what they’re doing every single day.

The Gold Coast Ingredients R&D team

Q:What could food scientists learn from chefs?

Barish: Food scientists need to learn about the art of food. Food scientists are very smart and very good at what they do. They’ve got the science down but they may not understand how flavors meld together. It would be helpful for them to be able to look at what they’re doing from a more artistic point of view. Even when you’re doing hardcore science and research if you take a step back and you look through the eyes of creativity, you may find another path to pursue.

Chefs understand how to manipulate food and how to make things taste really good. A lot of food scientists don’t know much about food, but each day they are working on how to make food taste better. Also, a lot of scientists work as individuals. As a chef you learn to work as a team. You can’t be an individual in a kitchen because if you’re not communicating with the grill chef or sauté chef, nothing is ever going to come up together. I know, for me, that’s one learning from my time as a chef that has really helped me in the lab.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

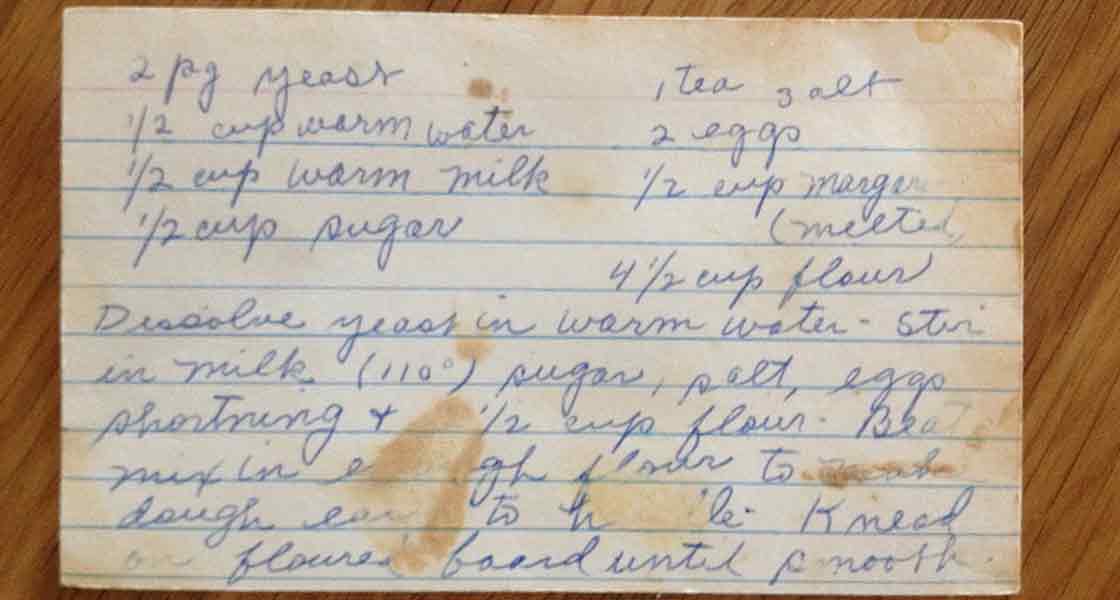

Grandmom Luby’s Onion Bread

Ingredients:

- 2 packages dry active yeast

- ½ cup warm water

- ½ cup warm whole milk

- ½ cup sugar

- 1 tsp salt

- 2 eggs, large

- ½ cup margarine (melted)

- ¼ cup caramelized onions, chopped

- 4 ½ cups flour, all-purpose

Method:

- In a large bowl, dissolve yeast in warm water.

- Add the milk, sugar, salt, eggs, margarine, and caramelized onions—mix well.

- Add ½ cup of flour and mix to incorporate.

- Working in increments, add enough flour to form a dough that’s easy to handle.

- Knead dough on a floured board until smooth.

- Place dough in an oiled bowl, cover, and allow to proof until doubled in size.

- Punch down and place in oiled pan, bake at 375°F until done.