Rediscovering Native American Cuisine

CULINARY POINT OF VIEW

Growing up on Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, Chef Sean Sherman’s childhood diet consisted primarily of processed and canned government-donated commodities. At 13, Sherman got his first restaurant job washing dishes, and quickly moved onto the line, continuing restaurant work through college and beyond. He has spent the past 10 years focused on uncovering the cooking techniques, ingredients, and flavors of the Oglala Sioux cuisine. Along the way, he launched the Tatanka Truck in Minneapolis, a food truck focused on indigenous food, as well as Sioux Chef, a catering company. Currently, he is working on a cookbook and planning to open a brick-and-mortar restaurant devoted to indigenous foods of Minnesota and the Dakotas.

© Heidi Ehalt

Q: When did your passion for exploring Native American cuisine begin?

Sean Sherman: Well, my career path has always been kind of focused on culinary even before I knew I was going to be a chef. Growing up on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota in the 70’s and 80’s there weren’t a lot of restaurants around. We grew up kind of poor, like a lot of people did on the reservation, so when my mom moved my sister and I off the reservation I started working in restaurants out of necessity. And I just kind of stayed with restaurant work all through high school, college, and post-college.

After college I moved to Minneapolis and worked my way up very quickly. It only took me a couple of years of being in Minneapolis before I got my first executive chef position. Then I began exploring lots of different kinds of cuisines and teaching myself about European-style foods—Italian, French, German, Asian, and African. Then I kind of hit a point in my chef career where I realized that I should be dealing with the food of my own personal heritage and ancestry.

When I started looking, I realized that there wasn’t very much information available in terms of Native American culinary history. So I started focusing on that for quite a few years. I tried to figure out for myself all the pieces that I needed to learn and understand, in order to educate myself on what Native American food was. I looked at how I grew up on the reservation and what foods were traditional and which foods had obviously been introduced at a certain point in time. I was slowly deciphering everything to reach the point where we are now with an indigenous food business.

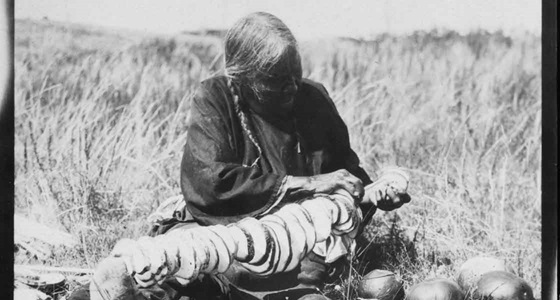

Native American woman drying squash slices—Photo courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society

Q: How did you go about discovering what those indigenous foods were?

Sherman: I always tell people like I couldn’t just go online and order a Joy of Native American Cooking book. I had to search in all sorts of different areas. I was really curious about the wild food aspect, so I taught myself a lot about foraging wild foods. I read a lot of books about the natural botany of the various regions I was studying. I read tons of historical texts. I was always kind of looking through historical pieces with a culinary lens and just trying to find any instance of people talking about food.

Also I tracked down either texts that were first-person from indigenous people or first-contact texts about when outside people encountered the tribes for the first time—before the culture become adulterated. I also talked to a lot of the elders.

Q: What foods are at the heart of the indigenous dishes of the Dakota and Minnesota territories?

Sherman: The Dakota and Minnesota territories make up a really large area with lots of different kinds of terroir—everything from the woodlands and the Great Lakes to the really fertile plains and grasslands. You also have areas like the Badlands, which is almost like desert landscapes immediately off of grassy plains. Then you get into the Black Hills, which is kind of an anomaly when it comes to small mountain ranges. It’s a bubble mountain range so it kind of bubbled from the bottom up. When you are at the top of the mountains you can find lots of ocean bed seashells and things like that.

There’s so much diversity in that range of terroir, so for us it’s about looking at the different regions and what kind of plants grow there. We’re looking at the communities that live there, their culture, and the way they handle food.

So, for example, there’s timpsila [prairie turnip] on the plains and all sorts of different herbs and varieties like purple coneflower, wild garlic, amaranth, and bergamot. When you get into the woodlands there’s different kinds of berries. We also have this wild rice that grows in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and up into Canada. It’s such a unique staple that grows in such a small area—if you look at it on a worldwide scale—so it’s really a special commodity. And, of course, there are lots of different kinds of animals, but our passion has really been more about plants.

Hand-harvested wild rice

Q: How do your preparations of the foods differ from what might have been done in the past?

Sherman: Well, we do have modern conveniences, so we have commercial kitchens and we’re in a modern world. Especially with a food business that has very strict rules and regulations when it comes to serving food to people. That being said, we try to keep everything as simple as possible. We dehydrate and slow-stew a lot of food. Also, we cook things directly, like grilling, because one of the simplest forms of cooking is to have a hot, flat rock that would act as a grill. We have really been very strict about using only indigenous ingredients when possible, to show people that it still can be done. For almost three years now we haven’t used any wheat flour, dairy, or sugar. Not even beef or chicken. There’s plenty of other protein options available, and other things that people ground into flours. Basically, we are taking all of that European culinary education and throwing it away and literally starting from the ground up. And just learning again from the plants around us.

Q: You’ve cooked for people in India, Italy, and the United Nations. What kind of responses have you received?

Sherman: I think people are really interested in what we are doing, especially right here in the United States. But we’ve traveled to Europe, India, and Mexico and everyone seems extremely interested in understanding what the true base of American food is, and the fact that you can’t talk about American history without the indigenous history because that’s where it began.

You have to go back to those roots to fully understand your region, and I think for the longest time, people were refusing to think about those that they displaced and the lands that they took over. They were happy to write their own history starting at the point of their arrival, but there’s so much more history that extends beyond that. Most of the rest of the world understands that because they still pay homage to things that happened thousands of years ago and for us it’s only been a couple hundred years.

I feel like the positive work that we’re doing—by bringing to light this healthy, local indigenous food base—can really help redefine American and North American food in general. America shouldn’t be defined by hamburgers, Coca-Cola, and craft beer, and Canada shouldn’t just be poutine. By understanding your indigenous history and the foods that people utilized, it makes for a deeper and richer story to tell.

© Becca Dilley

Q: Tell me a little bit about the cookbook you are working on.

Sherman: The manuscript is done and we’re expecting to be pre-selling in the next couple months and the book should be out on the shelves by the Fall. It’s being published through University of Minnesota Press and we feel like they’re going to do a great job. We touched on as much as we could in this first book, but there’s obviously so much more when it comes to indigenous food. We expect that there will be more books in the future.

We’re also looking at alternative ways of educating people—it might be some kind of video production. We’re also in the midst of opening a non-profit where we’re focused on culinary education and indigenous food business development. We really want to help people open up small businesses that are directed towards food and helping to alleviate the food access issue. We want people to have healthy food where they live.

We want to reach out to those indigenous communities and then by creating an educational center we’re hoping to bring people toward us. We’ll help train them on different pieces of indigenous foods, and all the different parts, whether it’s foraging, agriculture, food preservation, cooking, hunting, fishing, or salt and sugar production. There’s so much curriculum around it.

Q: You do a lot of work in the community and it’s obvious that this pursuit is not about having the hottest restaurant or being the top chef in the country. What is it that you hope to accomplish through your work?

Sherman: This work has always been bigger than myself so as a chef it has been nice to go into a food business and not have to worry about ego getting in the way. I am just trying to right a wrong. I grew up on the reservation with virtually no healthy food access and today seeing the effects of decades-long of bad diets—like diabetes. And it’s just due to what people have access to and what they’re used to. We want to reach out to educators and the children, so when they grow up they’ll know the difference between traditional food and poverty food. It’s our hope that this non-profit venture will really help us kind of get there by creating our own community of people to help make these visions come to life.

Q: The Indigenous Kitchen was one of the most well-funded Kickstarter restaurants ever. Is there an expected open date yet? Will the food be focused on the indigenous cuisine of the Upper-Midwest?

Sherman: We did a Kickstarter in September [2016], to raise $100,000 for seed money to start the restaurant, and we raised $150,000. That’s how we were in the top five of the most-funded restaurants and the most-backed one for restaurants for. It was nice to see all the support that that was out there.

What we want to do with the restaurant is team up with the non-profit that we’re creating to make a unique space that’s not only a restaurant but also a training center. We want this to be a modern indigenous kitchen, and we have this vision of being able to cook everything by wood fire. We also want to have a lot of green space outside to grow a lot of kind of permaculture foods that we love to utilize and have some test gardens to showcase some of these cool heirloom seed strains that we still have access to.

We’re hoping that as this restaurant model grows we can help develop smaller units near reservation areas around the country. It’s creating an indigenous infrastructure by bringing together all these partners with indigenous food growers and purveyors and then opening up peoples’ eyes to start thinking about indigenous history. And food is something that we all have in common and is so tangible.

Right now we’re in the midst of looking for locations that might work and then we’ll still need to continue to raise some funds but we’re hoping that doing this with the non-profit will help us move forward.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Cedar Maple Tea

Serves 6 to 8

Ingredients

- 8 to 10 cups water

- 3 6-inch cedar branches

Put the water into a large pot. Break the cedar branches into small chunks and add to the pot. Set the pot over medium-high heat and bring to a boil. Reduce the heat and simmer, tasting after about 10 minutes, until the tea has reached the desired potency. The longer it simmers the stronger it will taste. Remove from the heat and serve warm or chilled.