Combating Listeria Without Hysteria

FOOD SAFETY & QUALITY

Listeria contamination of foods is a major concern of the food industry and public health authorities, and work continues to be done to combat it through research and development, regulatory guidance, and educational programs. Of the six species of bacteria in the genus Listeria, Listeria monocytogenes is the primary species associated with foodborne illness. It causes a noninvasive gastrointestinal illness (listerial gastroenteritis) and a more serious invasive illness (listeriosis), which may cause septicemia, meningitis, and even death. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), listeriosis is responsible for 1,600 cases of foodborne illness and about 260 deaths in the United States each year. It is the third leading cause of death from foodborne illness. Pregnant women and their fetuses and newborns, people aged 65 and older, and people with weakened immune systems are most susceptible to listeriosis.

Listeria is found throughout the environment and is of particular concern with respect to ready-to-eat products because L. monocytogenes can grow in refrigerated foods and can survive in frozen foods for a long time. Since ready-to-eat products are often consumed without further cooking, there is a greater possibility of the occurrence of foodborne illness from these products if they become contaminated. Listeria species also exhibit tolerance to heat and salt and can form biofilms that may persist despite aggressive cleaning and sanitizing of food-contact surfaces.

According to the FDA’s Foodborne Pathogenic Microorganisms and Natural Toxins Handbook, referred to as the “Bad Bug Book,” foods that have been associated with L. monocytogenes contamination include raw milk, inadequately pasteurized milk, chocolate milk, cheeses (particularly soft cheeses), ice cream, raw vegetables, raw poultry and meat, fermented raw-meat sausages, hot dogs and deli meats, and raw and smoked fish and other seafood. There have been many recent food safety alerts and recalls linked to L. monocytogenes in ice cream, pet food, herring products, dairy products, hummus and products containing it, goji berry, cacao pods, ready-to-eat chicken breast strips, sliced deli meat products, fresh-cut vegetables, sunflower seeds, tamales, chicken fried rice, frozen waffles, smoked fish, frozen prepared foods, cookie dough, ready-to-eat chicken chili soup, and bacon.

Guidance for Industry

On January 17, 2017, the FDA published in the Federal Register a revision of the 2008 “Draft Guidance for Industry on Control of L. monocytogenes in Refrigerated or Frozen Ready-to-Eat (RTE) Foods,” requesting comments by July 17, 2017. The proposed revision reflects ongoing efforts by industry and government agencies to reduce the risk of L. monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods. The draft guidance emphasizes prevention, is consistent with the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), and reflects the FDA’s current good manufacturing practice (CGMP) requirements and the FSMA’s requirements for hazard analysis and risk-based preventive controls. The draft guidance incorporates industry best practices for sampling strategies and the seek-and-destroy approach used by the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), providing a more uniform federal approach to reducing the risk of environmental contamination with L. monocytogenes in plants. “Seek and destroy” refers to the recommendation to sample food-contact surfaces for Listeria species instead of L. monocytogenes, thereby increasing the chances of finding the pathogen.

The draft guidance includes recommendations for controls involving personnel, cleaning and maintenance of equipment, sanitation, treatments that kill L. monocytogenes, and formulations to prevent it from growing during storage of food between production and consumption. The draft guidance is intended to help companies comply with the CGMP requirements with respect to measures that can significantly minimize or prevent L. monocytogenes contamination of ready-to-eat food whenever it is exposed to the environment prior to packaging and the packaged food does not receive a treatment or control measure that would significantly minimize L. monocytogenes.

The FSIS’s “Compliance Guideline on Controlling Listeria monocytogenes in Post-lethality Exposed Ready-to-Eat Meat and Poultry Products,” issued in January 2014, points out that lethality treatments such as heat processing meat and poultry products generally eliminate L. monocytogenes but that ready-to-eat products can be recontaminated after the lethality treatment, during peeling, slicing, repackaging, and other processing steps. Examples of post-lethality treatments are steam pasteurization, hot water pasteurization, radiant heating, high-pressure processing, ultraviolet light treatment, infrared treatment, and drying (to lower water activity).

The FSIS guidance document “Best Practices for Controlling Listeria monocytogenes in Retail Delicatessens,” finalized in October 2015, presents specific recommendations for actions that deli retailers can take to control L. monocytogenes contamination of ready-to-eat meat and poultry products. It is based on actions identified by an interagency risk assessment; information from the FDA Food Code, scientific literature, and other guidance documents; and lessons learned from meat and poultry establishments. In January 2017 the FDA also issued a constituent update, “5 Steps Toward Working with FDA on Human and Animal Food Guidance Documents,” that explains how industry associations can work with the FDA in developing their own draft guidance documents that the agency may use to develop future guidance documents for the food industry.

Analytical Testing

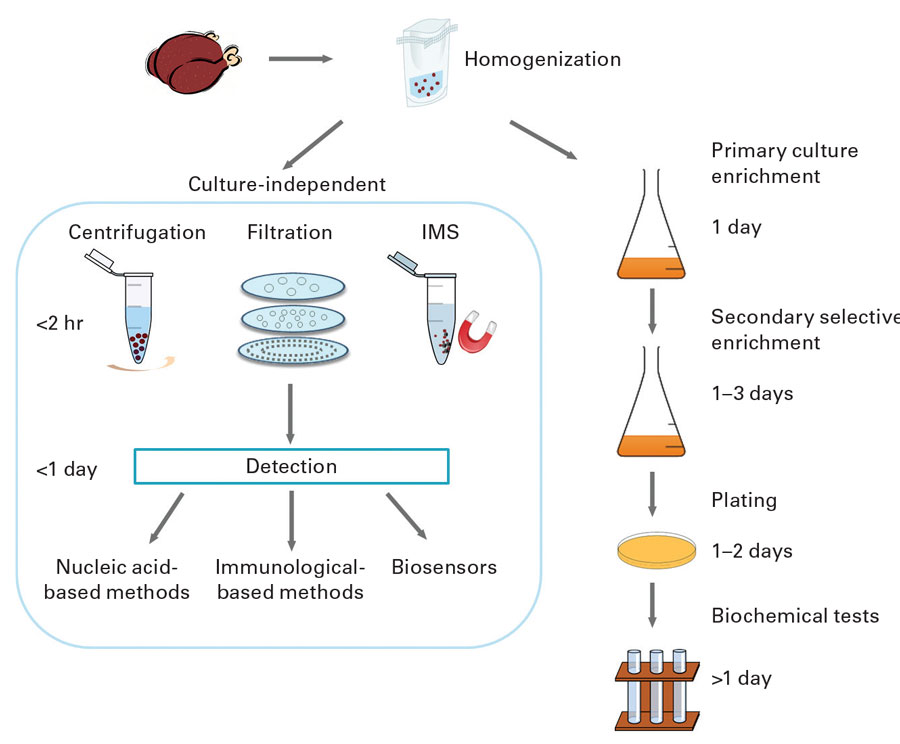

Tests for Listeria species detect L. monocytogenes and other Listeria species, but tests for L. monocytogenes does not detect other Listeria species. Sampling of production facilities for rapid detection of Listeria species is routinely used as an indicator of the potential presence of L. monocytogenes. Conventional culture-based detection methods require enrichment to allow for recovery of injured organisms and growth of Listeria to detectable levels. This can take 24–48 hours. Rapid methods and test kits have been developed and commercialized that do not require extensive enrichment. They include nucleic acid–based methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and variations such as quantitative PCR and real-time PCR, antibody-based assays such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and lateral-flow techniques, and biosensors. Bacterio-phage-based methods have also been developed and marketed.

The FDA has specified analytical methods for detection, isolation, and enumeration of L. monocytogenes and other Listeria species from foods in its Bacteriological Analytical Manual (BAM). Chapter 10, “Detection and Enumeration of Listeria monocytogenes in Foods,” states that the standard method involves 24–48 hours of enrichment in buffered Listeria enrichment broth followed by a variety of agars and biochemical confirmation. Total time to identification is 5–7 days. It states that certain rapid test kits approved as AOAC Official Methods of Analysis may be used to screen for the presence of Listeria and that isolates may be rapidly confirmed as L. monocytogenes by using specific test kits or PCR procedures. The kits are only approved for the food matrices specified in each official method. Negative results are considered definitive, and no further testing is required. Presumptive positive results with these rapid screening methods must be confirmed by streaking to selective agars and confirming isolates to the species level. The FDA has also specified test methods for food-contact surfaces and equipment in the food processing environment in the document “Testing Methodology for Listeria species or L. monocytogenes in Environmental Samples.”

The FDA and the FSIS emphasize that any method chosen for use by a food company should 1) be validated for testing relevant foods by a recognized independent body such as AOAC, AFNOR, MicroVal, or NordVal, 2) be included in the FSIS’s Microbiology Laboratory Guidebook or the FDA’s BAM, or 3) be an International Standards Organization method. The FSIS publishes on its website a list of test kits that have been validated by independent bodies for detection of Listeria, L. monocytogenes, and other foodborne pathogens and updates it quarterly. Included are those test kits certified by the AOAC Research Institute as Performance Tested Methods. The FSIS also provides guidance on the design of validation studies for pathogen testing methods in “Guidance for Test Kit Manufacturers, Laboratories: Evaluating the Performance of Pathogen Test Kit Methods” and guidance for manufacturers of meat, poultry, and egg products on choosing a microbiological testing laboratory in “Establishment Guidance for the Selection of a Commercial or Private Microbiological Testing Laboratory.”

Educating About Listeria

The FDA, FSIS, and CDC all provide information on Listeria via their websites, as do the manufacturers of test kits and other organizations. In addition, various organizations provide information, educational programs, and workshops on Listeria. The Produce Marketing Association (PMA) and the United Fresh Produce Association in September 2016 established a joint working group to, among other things, identify produce-specific L. monocytogenes research needs and funding sources and share information about research results and educational resources, such as through the PMA’s Listeria Resources website. The Food Safety Consortium Conference in December 2016 included a “Listeria Detection & Control Workshop.” In May 2017 the Food Safety Summit will include a workshop on the latest in Listeria control. The North American Meat Institute will present an “Advanced Listeria monocytogenes Intervention and Control Workshop” in Kansas City, Mo., in October 2017. The International Association for Food Protection will have several sessions on Listeria at its annual meeting in Tampa, Fla., in July 2017 and has available several webinars on Listeria. And the Institute of Food Technologists’ IFT17 scientific program will feature a symposium on preventive controls in food manufacturing and papers on pathogen control.

Neil H. Mermelstein, IFT Fellow,

Neil H. Mermelstein, IFT Fellow,

Editor Emeritus of Food Technology

[email protected]