Food Companies Get Smart About Artificial Intelligence

AI and machine learning are adding value to product development and sensory evaluation, not to mention operations and logistics. Here’s a look at how some progressive players—both established giants and entrepreneurial innovators—are applying these technologies.

Article Content

For Nestlé and Nuritas, artificial intelligence (AI) is helping identify proteins that lead to healthier foods. Kraft Heinz’s focus for now is using AI to optimize operations and enhance relationships with stores, sales reps, and consumers. Kroger plans to leverage AI through a new investment in start-up distribution specialist Ocado. And Domino’s is harnessing AI to help with phone orders of pizza.

The food business finally is doing a deep dive with artificial intelligence and its close companion, machine learning (ML). A fleet of start-ups is hoping to exponentially improve the process of ingredient discovery and development, trying to optimize seed cultivation and livestock output, and improving customization of commercial diets. Established giants are trying to keep pace by using AI and ML in product R&D as well as across the spectrum of operations and relationships.

“We keep finding areas where AI and ML can be applied to help our organization ‘be the best food company,’” says Francesco Tinto, global chief information officer for Kraft Heinz, citing the company’s slogan. “The road to leverage [these technologies] is not a destination but more like a journey.”

It’s a journey that must be hurried. Traditional food and beverage companies are struggling mightily with competition from start-ups and private labels, and food industry employees—from CEOs to factory workers—are losing their jobs in the process. So they’re pressing AI and ML into service across the board, perhaps most promisingly in improving and accelerating product innovation.

“About 95% of new food and beverage products fail in their first three years on the market,” says Jason Cohen, founder and chief executive officer of Analytical Flavor Systems, a start-up that uses AI and ML to predict humans’ perceptions of flavor, aroma, and texture—and, by proxy, predicts the chances of success for a new product. “It doesn’t matter the size or category or level of R&D spending: Failure rates from concept development are through the roof.”

“About 95% of new food and beverage products fail in their first three years on the market,” says Jason Cohen, founder and chief executive officer of Analytical Flavor Systems, a start-up that uses AI and ML to predict humans’ perceptions of flavor, aroma, and texture—and, by proxy, predicts the chances of success for a new product. “It doesn’t matter the size or category or level of R&D spending: Failure rates from concept development are through the roof.”

Playing Catch-Up

But the business is behind in AI, just as it was initially in e-commerce. The food and beverage industry doesn’t even register on an “AI Heatmap” of deals distribution in 24 verticals compiled by CB Insights, where health care and advertising are two of the most active; agriculture is No. 17. And pharmaceuticals, a business closely related to food, has darted ahead of it in AI, partly because the payoffs from discovering new drugs can be enormous, which is not necessarily the case in foods and beverages.

Food and beverage companies also typically are among the least prepared to exploit the power of AI and ML because of deficiencies in the raw material required by those technologies: data to crunch, massage, and extrapolate from.

“We in the industry haven’t been generating as much data as other industries where this can be applied,” says Tony DeLio, senior vice president of corporate strategy and innovation for Ingredion, a major ingredient developer and supplier. “We haven’t necessarily done a good job of structuring the data as we’ve captured it so we can utilize it. And, honestly, the industry really hasn’t focused on this until now because the cost has been too high.”

“We in the industry haven’t been generating as much data as other industries where this can be applied,” says Tony DeLio, senior vice president of corporate strategy and innovation for Ingredion, a major ingredient developer and supplier. “We haven’t necessarily done a good job of structuring the data as we’ve captured it so we can utilize it. And, honestly, the industry really hasn’t focused on this until now because the cost has been too high.”

Another reality is that AI is not a panacea. For one thing, its emphasis on engineering may seem at cross-purposes with the biggest trend in the industry: consumer demand for the pure and natural, unadulterated and unaltered. “No one wants to feel like they’re eating Frankenfood,” says Ken Harris, managing director of Cadent Consulting, which works with food companies.

Also, some early flame-outs damaged AI’s reputation in the industry. Seven-year-old Hampton Creek was a start-up sensation, with founder Joshua Tetrick initially promising a stream of plant-based products and lately patenting an AI system dubbed “Blackbird” to research proteins at the molecular level. But Tetrick squandered early retailer and consumer fascination with Hampton Creek and products such as Just Mayo, sinking into financial scandal, legal battles, and food safety concerns that prompted Target to remove its products from shelves last year.

Accelerating Discovery

Accelerating Discovery

Nuritas hopes for far better results. Founder Nora Khaldi is an Irish mathematician who established the company in 2014 to use AI and genomics to identify bioactive peptides in plants that could provide health benefits in foods. Early investors, to the tune of a total of $30 million, include U2’s Bono and Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff.

“I recognized that the industry was taking too long—seven to 10 years and at least $35 million—identifying one scientifically proven ingredient that could benefit human health, and even with all of that, only at an accuracy rate of 0.1 percent,” says Khaldi.

Peptides are the most potent molecules in food because “every signal that occurs in the human body is based on peptide attraction of DNA,” Khaldi explains. “Yet there are billions of peptides in a common apple, and most of them haven’t yet even been found, much less analyzed. We came up with an accelerated way to find things that have always been there, but humankind has never been able to find them.”

The Nuritas AI platform combines the company’s own research with two centuries of scientific literature, patents, and other information sources to target diseases and conditions including diabetes, aging, and loss of muscle mass. It predicts which peptides might help. Then Nuritas scientists try to “unlock” the substance for real-world applications. Machine learning all along improves the process, which has been shown to identify peptides 10 times faster and 500 times more accurately while significantly cutting costs, the company says.

Already, Nuritas has reached a deal with Nestlé to identify and exploit peptides for a health-oriented application that neither company will disclose. Nuritas also has partnered with BASF to commercialize a network of its existing peptides as an anti-inflammatory ingredient in medical foods, supplements, and functional foods, and to work in other areas of interest for the Germany-based chemical giant.

And Khaldi believes it won’t be long before Nuritas helps a CPG company develop a nutrition bar for prediabetics. “They could consume it on a daily basis to prevent them from going to diabetes,” she says. “There’s nothing on the market that does that.”

Applying AI to Sensory Analysis

Analytical Flavor Systems harnesses AI and ML for a different purpose: identifying ingredients and foods that consumers will love and selling that research to food and beverage companies.

In a drive to help clients come up with hyper-personalized foods, the company takes three sources of data—its own R&D, large-scale consumer panels, and tastings by client CPG companies—and plugs it into an AI-based algorithm that helps overcome the predictive shortcomings of traditional methods.

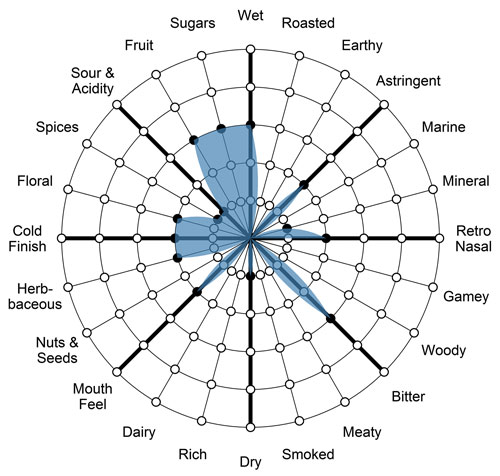

Its Gastrograph is a smart phone app whose central feature is a wheel with 24 spokes, where each sliver represents a discrete category of sensory experience, such as “meaty,” “bitter,” or “mouthfeel.” Research participants indicate the intensity of their perceptions of a product along these specifications. It also gathers demographic and lifestyle data.

“We can translate all the data into target markets and tastes, so we can model preferences,” Cohen says. “And once we understand what individual demographics taste in products, we can predict what they like and dislike.”

The algorithm also makes decisions about whether the taste preferences of various cohorts are expressions of physiological characteristics or learned behaviors. It can help predict predilections for flavors that testers can’t name or maybe have never experienced before. And if, for example, there are no Germans on the taste panels, Gastrograph infers what Germans would like anyway.

Another start-up, FlavorWiki, uses AI and ML to extrapolate taste preferences and help established food companies and start-ups alike avoid the expense of continually engaging large panels of consumers or high-cost, sensory-trained tasters.

“We’ve built an algorithm that is able to process simple digital inputs that an untrained person can give us, say distinguishing between two flavors and textures rather than having to scale them—and then it develops those into profiles,” says founder Daniel Protz. “Over time, working with actual panels, FlavorWiki optimizes the data.”

“We’ve built an algorithm that is able to process simple digital inputs that an untrained person can give us, say distinguishing between two flavors and textures rather than having to scale them—and then it develops those into profiles,” says founder Daniel Protz. “Over time, working with actual panels, FlavorWiki optimizes the data.”

FlavorWiki also helps clients understand what factors truly drive satisfaction as consumers experience existing products. “It’s not actually really known,” Protz said, “why many successful brands and products succeed.”

AI in Product Development

Among old-line food companies, Harris says, use of AI so far has fallen into two main camps. First, big beverage companies are harnessing the technologies in an unending search for sweeteners that replicate the appeal of sugar without the calories, after current alternatives ranging from aspartame to stevia haven’t provided an ultimate solution.

Beverage makers are among the industry’s most active users of AI applications in product development. Coca-Cola, for instance, last year decided to launch Cherry Sprite as a new flavor based on monitoring data collected from the latest generation of self-service soft-drink fountains, Freestyle, which allow customers to mix their own drinks. And Carlsberg has launched the Beer Fingerprinting Project, which uses AI to reduce time and cost in developing new types of beer, in conjunction with Microsoft, with an advanced “sensor platform” that can determine complex flavor compounds in beverages.

A second tranche of interest in AI by the established industry is ingredient and end-goods companies “trying to create products using different elements to come up with food that is essentially better in nutrients but has the look, taste, touch, and feel of things that we’re familiar with,” Harris says.

Ingredion is one of those. Helped by the fact that off-the-shelf AI algorithms have become practically free over the past few years, the company is scrambling to use AI and ML to turbocharge substance discovery and experimentation. “We’re starting that journey, and it’s exciting,” DeLio says.

For example, Ingredion has hired AI experts and has begun applying the techniques to starch and other texturizers, soon to move on to more classes of ingredients. The company is agglomerating data from three primary sources to feed AI’s capabilities: information on consumers, sensory data that it has been accumulating for decades, and a new system for generating texture data called Texture Robotics Experimenter.

“T-Rex” is a series of nine different robots that perform a range of texture measurements to help understand how a product’s performance is affected by other ingredients or by conditions such as cooking temperatures and times, and process shear. The platform can precisely screen texture systems up to 10 times faster than traditional methods, which may have involved scouring the world for dozens of existing products and testing some with consumers. T-Rex nicely tees up all this great new data for AI applications.

“With AI starting to come into play,” DeLio explains, “we can start to project. We can link in more of the sensory stuff with the rheological data so that we can start to predict an optimized texture for, say, a yogurt product. And if someone wants to mimic this sort of texture, we can go in and, through our system, pretty accurately define an ingredient solution that gets you to that texture.”

Similarly, Kraft Heinz is experimenting with AI and ML in product development as well as packaging, Tinto says. “We believe there are opportunities hidden in multiple places in the organization, and we are actively looking to uncover hidden gems anywhere we can find them,” he says. The company’s “analytics innovation process allows us to test and learn quickly across all areas of the company and geographies to look for opportunities to leverage new ways of working, using advanced analytical techniques.”

Still, Tinto, DeLio, and peers across the CPG industry are running into complications as they grapple with a technology that they know will help dictate their future.

For one thing, DeLio says, “Food is complex.” He began his career in instant coffee, searching for aromas among 3,000 identified flavor ingredients. “If you got one of them wrong,” he says, “it’s, ‘This one smells like burning tires.’”

The psychological nature of food consumption can throw curves that even the best AI and ML can’t solve so far. “Pharma can develop AI operations that measure very specific things, but it’s simpler because there’s only one output, and you don’t worry about too much other than that,” DeLio says. “But what’s handicapped the food industry is that most decisions on formulation come down to tasting it, and capturing what humans think is a very complex process of assimilating a lot of inputs.”

Thinking Beyond Algorithms

Cathy Kapica agrees. “Especially thinking about food, there is an irrational aspect as well as a huge emotional component that no algorithm is going to be able to capture,” says the food scientist who formerly was global head of nutrition for McDonald’s and now leads the Awegrin Institute, a food policy think tank. “Those things you’re not going to get from AI until we get a quantum computer.”

Kapica further argues that AI can lead down rabbit holes in the food and beverage industry if it’s misdirected in the first place. “AI is only as good as the programmer who’s programming the thing,” she says. “That’s especially important with product development, where human creativity and innovation are crucial. Technology can’t do everything. And to think that you can replace humans—especially around something like food—is short-sighted, especially in consumer preferences, which change. Humans can’t even predict what humans will do.”

For example, Kapica says, AI and ML were unlikely to have presaged today’s boom in gluten-free foods by extrapolating demand from existing products. “Who would have thought gluten-free would be a big deal despite how it tastes?” she says. “An algorithm wouldn’t have predicted that.”

Another example: AI and ML can’t suggest “healthy” or “nutritious” foods because “there’s no consensus on what that means,” Kapica says. “So if we can’t agree on the parameters for an algorithm in this area, you’d have, ‘Garbage in; garbage out.’”

Food companies also must learn to interpret their growing interest in AI and ML for consumers and other constituencies who have been pulling them strongly in the direction of transparency and simplicity in every phase of their operations, especially in product formulations, supply-chain sourcing, and packaging.

“AI has the potential to transform food and beverage, but with challenges that other verticals don’t have,” says Harris. “It isn’t the benefit of the technology and the accelerated learning that’s the issue, but rather the countervailing demands from consumers for authenticity and simple, natural ingredients.”

For such reasons, Harris says, some CPG companies have looked at making significant investments in AI and ML and have backed off, choosing at least for now to stick with conventional means of product development.

“They’re sophisticated,” he says of these companies, which he declined to identify. “But they’re trying to go back to creating food using very tried-and-true methods and forcing themselves to use worn-out tools to do it.”

Still, in an industry that has only begun to touch on the possibilities for artificial intelligence and machine learning, even these companies might not be holdouts for long.

IFTNEXT is made possible through the generous support of Ingredion, IFT’s Platinum Innovation Sponsor.

Dale Buss is a freelance writer based in Rochester Hills, Mich. ([email protected]).

For those seeking to live healthfully, hundreds of diet options are available, and finding the most optimal can be challenging. One of the biggest promises of artificial intelligence and machine learning for the food business is to give consumers a choice of just one diet: the one that’s individualized for them alone.

For those seeking to live healthfully, hundreds of diet options are available, and finding the most optimal can be challenging. One of the biggest promises of artificial intelligence and machine learning for the food business is to give consumers a choice of just one diet: the one that’s individualized for them alone. Their ranks include some of the most disciplined manufacturers, distributors, marketers, and salespeople in the world, so it’s little surprise that operations teams tend to be at the leading edge of food industry artificial intelligence and machine learning applications.

Their ranks include some of the most disciplined manufacturers, distributors, marketers, and salespeople in the world, so it’s little surprise that operations teams tend to be at the leading edge of food industry artificial intelligence and machine learning applications. Kraft Heinz is typical of CPG companies that are trying to get their arms around all the various capabilities of AI—before the competition does. Global Chief Information Officer Francesco Tinto is pressing AI and machine learning into every crook and crevasse across the $25-billion enterprise, identifying waste, inefficiencies, and areas ripe for trimming and optimization in manufacturing, supply chains, sales, and even IT itself.

Kraft Heinz is typical of CPG companies that are trying to get their arms around all the various capabilities of AI—before the competition does. Global Chief Information Officer Francesco Tinto is pressing AI and machine learning into every crook and crevasse across the $25-billion enterprise, identifying waste, inefficiencies, and areas ripe for trimming and optimization in manufacturing, supply chains, sales, and even IT itself.