Combating Antibiotic Resistance

FOOD SAFETY AND QUALITY

An antimicrobial is anything that inhibits or kills microbial cells, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Antibiotics are antimicrobials that target bacteria. They either prevent the reproduction of bacteria or kill bacteria by dissolving the bacteria’s cell membranes or affecting the bacteria’s protein-building or DNA-copying process. Some antibiotics are effective only against specific bacteria while others target a wide range of bacteria.

An antimicrobial is anything that inhibits or kills microbial cells, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Antibiotics are antimicrobials that target bacteria. They either prevent the reproduction of bacteria or kill bacteria by dissolving the bacteria’s cell membranes or affecting the bacteria’s protein-building or DNA-copying process. Some antibiotics are effective only against specific bacteria while others target a wide range of bacteria.

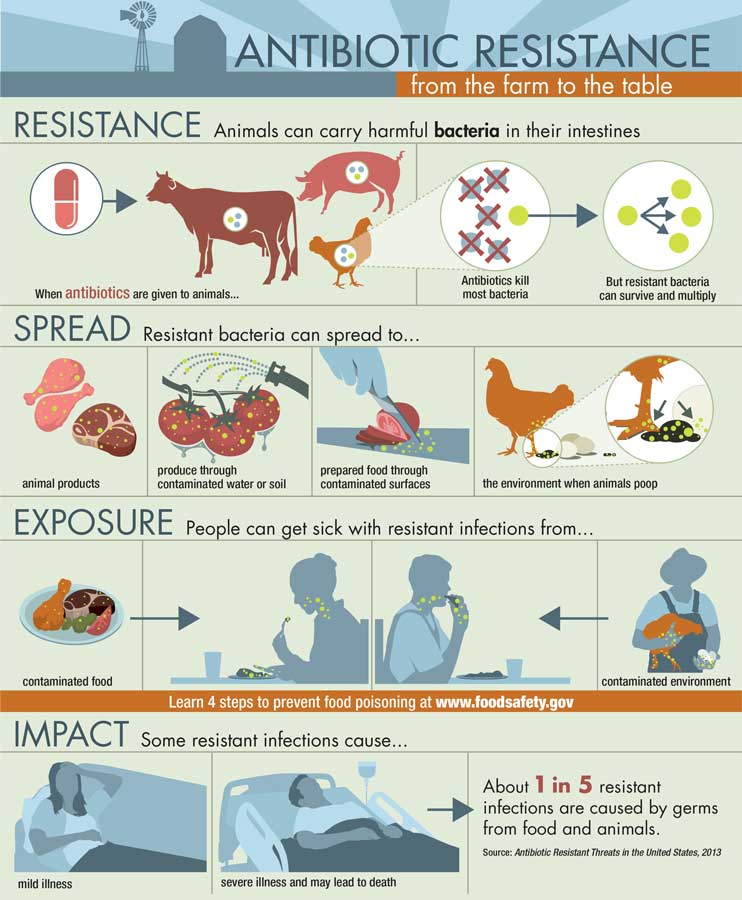

Besides being used to treat human illnesses, antibiotics are widely used to treat bacterial infections in food-producing animals such as cattle, swine, poultry, and fish. However, a major problem around the world today is that important bacterial infections are developing resistance to some antibiotics. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), every year more than two million people in the United States get infections that are resistant to one or more antibiotics, and at least 23,000 people die as a result. Some bacteria are naturally resistant to antibiotics, and others may become resistant if they are not completely killed by an antibiotic.

Unnecessary use of antibiotics is considered a major cause of antibiotic resistance, and many approaches have been taken to address it, including banning the use of antibiotics that are used solely for agricultural production purposes and educating consumers about inappropriate uses of antibiotics. The World Health Organization has recommended that farmers stop routinely using antibiotics to promote growth and prevent disease in healthy animals, and Antibiotic Awareness Week activities are held around the world each year in November to raise awareness of the threat of antibiotic resistance and the importance of appropriate antibiotic prescribing and use. Inappropriate uses of antibiotics by humans include inappropriate prescribing, sharing medicines, not taking antibiotics as recommended, and taking antibiotics for viral infections such as a cold or the flu.

Phasing Out Production Uses

Antibiotics are used to treat food-producing animals that have been diagnosed with an illness, to control the spread of an illness on a farm or ranch in the face of an outbreak, and, under the supervision of a veterinarian, to prevent illness when livestock are particularly at risk. Until recently, antibiotics were also used to promote growth or increase feed efficiency. To reduce the possibility that the use of antibiotics in food animals may result in increased resistance to antibiotics in humans, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued Guidance for Industry (GFI) 209, “The Judicious Use of Medically Important Antimicrobial Drugs in Food-Producing Animals,” in April 2012, and GFI 213, “New Animal Drugs and New Animal Drug Combination Products Administered in or on Medicated Feed or Drinking Water of Food-Producing Animals: Recommendations for Drug Sponsors for Voluntarily Aligning Product Use Conditions with GFI No. 209,” in December 2013. GFI 209 outlined the agency’s position on phasing out growth-promotion claims and phasing in veterinary oversight, and GFI 213 outlined a three-year plan calling on animal-drug companies to remove from their product labels indications for use related to growth promotion and bring the remaining therapeutic uses under the oversight of licensed veterinarians by switching their marketing status from over-the-counter (OTC) to either prescription or Veterinary Feed Directive (VFD). In June 2015, the FDA updated its VFD rule to improve the efficiency of the requirements regarding how VFD drugs are used and distributed. On January 1, 2017, the FDA announced that implementation with GFI 213 had been completed and that all affected animal drug companies had voluntarily withdrawn 84 approved drug applications and converted 93 applications for oral dosage products for use in water from OTC status to prescription status and 115 applications for products for use in feed from OTC to VFD status. Growth-promotion indications were withdrawn for 31 applications.

National Action Plan

The White House in March 2015 issued the National Action Plan on Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria (CARB) to reduce by 2020 the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria by slowing the emergence of resistant bacteria and preventing the spread of resistant infections; strengthening national surveillance efforts to combat resistance; advancing development and use of rapid and innovative diagnostic tests for identification of resistant bacteria; accelerating research and development (R&D) for new antibiotics, other therapeutics, and preventive strategies, including vaccines; and improving international collaboration and capacities for antibiotic-resistance prevention, surveillance, control, and R&D.

The U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services (HHS) reported during Antibiotic Awareness Week in November 2017 on the progress that the Interagency CARB Task Force had made during the first two years of implementation of the action plan. The following are some of the highlights in the October 2017 report: The CDC established the Antibiotic Resistance Laboratory Network of seven regional laboratories to better detect, respond to, and contain resistance and resistant infections. The USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service updated its National Veterinary Accreditation Program for licensed veterinarians, which includes training module 23, “Use of Antibiotics in Animals.” The National Institutes of Health (NIH) invested in research exploring novel approaches to address diagnostics for antimicrobial resistance, including host-targeted therapeutics, microbiome-based therapeutics, bacteriophage, phage lysins, biofilm inhibitors, anti-virulence strategies, immune-based therapies, and others. The FDA approved, cleared, or granted authorization for marketing several new diagnostic devices for detection of antibiotic resistance. The USDA’s Agricultural Research Service implemented R&D projects on alternatives to antibiotics, such as vaccines, bacterial-derived products, immune-related products, phytochemicals, and other chemicals and enzymes. The USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture in 2015 funded a project on voluntary compliance in antimicrobial stewardship of beef and dairy production systems and in 2016 funded basic research projects to develop novel systems approaches to investigate the ecology of antibiotic resistance; alternative practices that mitigate emergence, spread, or persistence of resistant pathogens within the agricultural ecosystems; critical control points for mitigating antimicrobial resistance preharvest and postharvest; innovative training, education, and outreach resources; and design studies to evaluate impacts.

The U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services (HHS) reported during Antibiotic Awareness Week in November 2017 on the progress that the Interagency CARB Task Force had made during the first two years of implementation of the action plan. The following are some of the highlights in the October 2017 report: The CDC established the Antibiotic Resistance Laboratory Network of seven regional laboratories to better detect, respond to, and contain resistance and resistant infections. The USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service updated its National Veterinary Accreditation Program for licensed veterinarians, which includes training module 23, “Use of Antibiotics in Animals.” The National Institutes of Health (NIH) invested in research exploring novel approaches to address diagnostics for antimicrobial resistance, including host-targeted therapeutics, microbiome-based therapeutics, bacteriophage, phage lysins, biofilm inhibitors, anti-virulence strategies, immune-based therapies, and others. The FDA approved, cleared, or granted authorization for marketing several new diagnostic devices for detection of antibiotic resistance. The USDA’s Agricultural Research Service implemented R&D projects on alternatives to antibiotics, such as vaccines, bacterial-derived products, immune-related products, phytochemicals, and other chemicals and enzymes. The USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture in 2015 funded a project on voluntary compliance in antimicrobial stewardship of beef and dairy production systems and in 2016 funded basic research projects to develop novel systems approaches to investigate the ecology of antibiotic resistance; alternative practices that mitigate emergence, spread, or persistence of resistant pathogens within the agricultural ecosystems; critical control points for mitigating antimicrobial resistance preharvest and postharvest; innovative training, education, and outreach resources; and design studies to evaluate impacts.

Incentivizing R&D

The HHS in September 2015 established the Presidential Advisory Council on Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria to recommend programs and policies regarding antimicrobial resistance. In March 2015, the council issued “Initial Assessments of the National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria,” in which it agreed to propose recommendations for incentivizing the development of new products to reduce the spread of antibiotic resistance for humans and animals. The council said that although the contribution that the administration of antibiotics to food animals makes to the overall problem of antibiotic resistance in foodborne bacteria and in medical settings remains to be quantified, selective pressures from antibiotic use in any setting will likely increase the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria; therefore, opportunities to replace, refine, or reduce antibiotic use should be examined. The council established three working groups focusing on incentives for vaccines, diagnostics, and therapeutics/anti-infectives. The working groups identified 45 critical issues that hinder the development of new and improved products and proposed 64 recommendations to address them.

The council in September 2017 issued the report “Recommendations for Incentivizing the Development of Vaccines, Diagnostics, and Therapeutics to Combat Antibiotic-Resistance,” which was divided into sections on human health and animal health. With regard to animal health, the council recommended drafting a National Policy on Innovation for Food Animal Disease Interventions and creating an interagency innovation institute, situated within the USDA, to facilitate public-private partnerships for R&D related to antimicrobial resistance. With regard to vaccines, the council recommended funding to incentivize use of vaccines that reduce bacterial and viral disease prevalence in farm animals to reduce the need for antibiotics; funding to support basic research on immune systems across species to optimize vaccine and adjuvant development; studies to estimate the amount of antibiotic use that can be eliminated with vaccines, including viral disease vaccines; and education and training in assessing the effectiveness of disease prevention programs that balance productivity and welfare through improvements in veterinary and animal science curricula, continuing education, and funding for training programs that assess herd and flock health programs.

With regard to diagnostics for animal use, the council recommended funding for clinical trials to enhance understanding of the animal health and potential human health risks and benefits associated with clinical decisions involving antibiotic use and ongoing funding for veterinary diagnostic laboratories that perform diagnostic testing and antimicrobial susceptibility testing for animal pathogens. And with regard to R&D, the council recommended funding for research on diagnostics that rapidly identify pathogens in food animals or provide rapid susceptibility results directly from clinical specimens in the field setting, translational research to adapt diagnostics platforms developed for humans to animals, and research to develop culture-independent methods for detecting microbial contamination of carcasses and meats as a tool for improved process controls.

Animal Stewardship

Stewardship (careful and responsible management) of food-producing animals is an important aspect of the fight against antibiotic resistance. In the report “Antibiotic Resistant Threats in the United States 2013,” the CDC said that the number-one contributing factor to the development of antimicrobial resistance is overuse in humans, but it also emphasized the need for good antibiotic stewardship among livestock and poultry farmers. Food-animal associations recognize this and offer stewardship guidelines. For example, the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association has incorporated antimicrobial stewardship guidelines into its Beef Quality Assurance program, which includes the manual “Antibiotic Stewardship for Beef Producers”; the dairy industry’s National Dairy FARM Program offers the “Milk and Dairy Beef Drug Residue Prevention Reference Manual 2017,” which addresses the judicious and responsible use of antibiotics and avoidance of drug residues in milk and meat; and the National Pork Board offers the “Pork Industry Guide to Responsible Antibiotic Use” and other information regarding antibiotic resistance and residues.

Veterinary associations have also prepared stewardship plans. For example, the American Veterinary Medicine Association has issued the policy “Antimicrobial Stewardship Definition and Core Principles,” which identifies core principles of stewardship that should be considered in developing species-specific stewardship plans. And the American Association of Bovine Practitioners has issued “Key Elements for Implementing Antimicrobial Stewardship Plans in Bovine Veterinary Practices Working with Beef and Dairy Operations” to provide bovine veterinarians with guidelines for designing, implementing, and monitoring antimicrobial stewardship programs.

The USDA’s 2015 Antimicrobial Resistance Action Plan called for enhanced monitoring of antimicrobial use in food-producing animals, and the USDA’s National Animal Health Monitoring System conducted studies on antimicrobial use and stewardship practices on beef feedlots in 2017 and swine farms in 2016 before implementation of the FDA’s policy changes. Expected to be conducted biennially, the studies covered antimicrobial stewardship practices, such as recordkeeping related to antimicrobial use, whether a veterinarian was consulted in the decision to use antimicrobials, how and why antimicrobials are used, and the percentage of operations using specific antimicrobials.

Advancing Antibacterial Innovation

Several government funding opportunities have been encouraging development of new antimicrobials and rapid methods for diagnosing and treating drug-resistant bacterial infections. The CARB-X Challenge, a five-year event designed to accelerate the development of new antibiotics, vaccines, and other therapeutics and products to tackle antibiotic resistance, was launched in July 2016. CARB-X is a nonprofit partnership created in response to the U.S. government’s 2015 CARB initiative and the United Kingdom’s call in 2016 for a concerted global effort to tackle antibiotic resistance. It is funded by the HHS’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) and the Wellcome Trust with in-kind support from the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The partnership provides financial and scientific support to accelerate the most promising research projects from around the world through the early stages of product development so that they can attract additional private or public investment for clinical-stage development. By November 2017, CARB-X had granted awards to 24 biotechnology companies and research teams in six countries. The projects include 22 early-development R&D projects investigating seven new classes of antibiotics, 10 nontraditional antibiotics, 10 new molecular targets, and a rapid diagnostic to determine the type of drug-resistant bacteria that is causing an infection.

The Antimicrobial Resistance Diagnostic Challenge, a competition to develop tests that identify antibiotic-resistant bacteria or distinguish between viral and bacterial infections to reduce unnecessary use of antibiotics at point of care, was launched in September 2016 by the NIH and BARDA. In March 2017, 10 entries were selected from among 74 submissions as semifinalists in step one of the three-step competition; each entrant received $50,000 to develop concepts into prototypes. In addition to the 10 semifinalists from step one, others can submit a prototype to compete in step two without having been a semifinalist in step one. The deadline for submissions of prototypes for step two is September 4, 2018, and up to 10 finalists will be selected on December 3, 2018, and receive up to $100,000. Their prototypes will be evaluated in step three, and up to three winners will be announced on July 31, 2020, to share an amount up to $20 million.

The different approaches taken by the semifinalists included measuring immune biomarkers from a single blood sample; diagnosis based on differences in the breath volatile metabolite profiles of patients with bacterial versus viral pneumonia; digital nonmagnified imaging to count fluorescently labeled cellular and molecular targets; use of rapid multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to distinguish bacterial infection, viral infection, and no infection; detection of infection biomarker in a single drop of blood; a disposable, molecular PCR diagnostic device for antimicrobial resistance detection; a rapid test for characterizing the presence or absence of pathogenic microorganisms in blood and urine samples and a rapid test for characterizing the functional minimum inhibitory concentration of an antimicrobial to suppress the growth of the pathogen; a microfluidic sensor that counts and weighs individual microbes at high throughput and measures bacterial culture growth; use of transcriptional profiling to distinguish bacterial and viral respiratory infection; and measurement of the response of a patient’s airway cells to tell whether the body is fighting a viral infection or a bacterial infection.

Neil H. Mermelstein, IFT Fellow, Editor Emeritus of Food Technology

Neil H. Mermelstein, IFT Fellow, Editor Emeritus of Food Technology

[email protected]