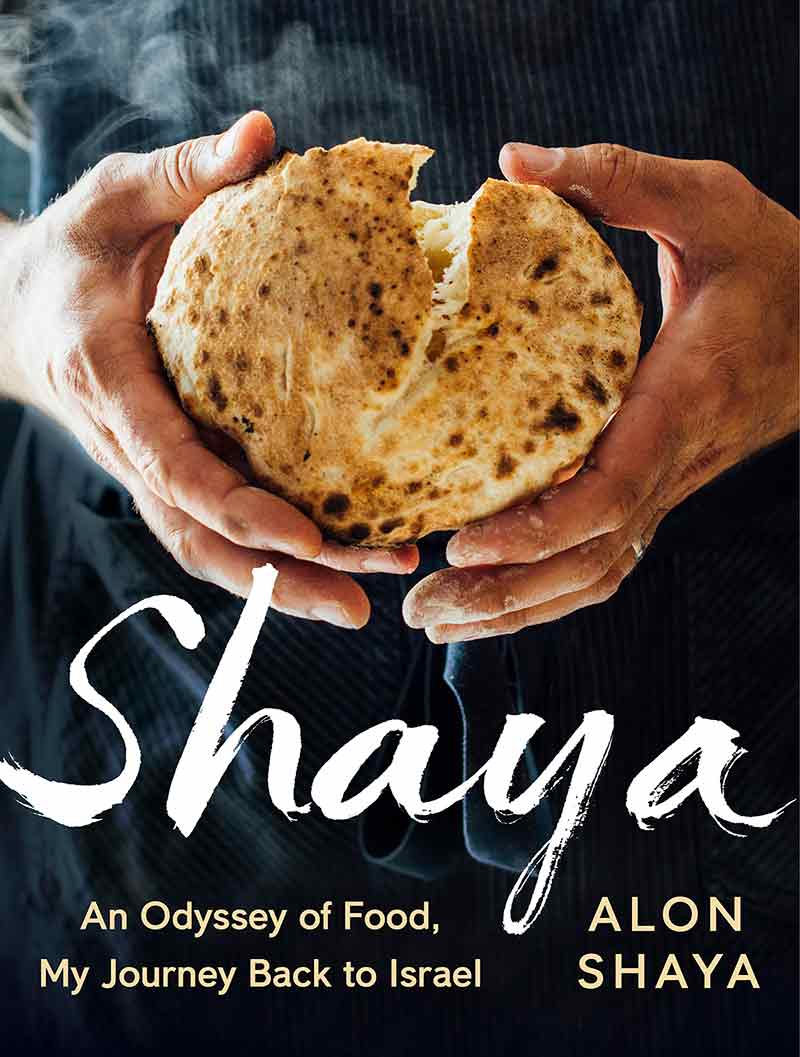

Chef Shaya Reconnects With His Israeli Roots

CULINARY POINT OF VIEW

Recipe: Moroccan Carrot Salad

Israel-born and New Orleans–based chef Alon Shaya first learned to cook from his grandmother when she visited Philadelphia, where he was raised. With the guidance of his home economics teacher, Shaya attended the Culinary Institute of America, and went on to cook at restaurants in Las Vegas, St. Louis, and Italy. Within the past five years, Shaya has returned to his cooking roots and is now the owner of two restaurants, Saba in New Orleans, and Safta in Denver, serving upscale Israeli dishes imbued with New Orleans’ ingredients.

Q: You named your restaurants after your grandmother and grandfather. What impact did they have on your culinary journey?

Alon Shaya: They had a huge impact. My grandmother really got me to fall in love with food from a very young age. Cooking with her was more than just preparing meals—it was being together with family. My family immigrated from Israel to America when I was four, but my grandparents still lived in Israel. So, whenever they would visit us in Philadelphia, it was always centered around food. It was the one thing that made us feel like we were back home again.

Q: In your cookbook you liken Israeli food to gumbo. Why is that an apt comparison?

Q: In your cookbook you liken Israeli food to gumbo. Why is that an apt comparison?

Shaya: Gumbo is a melting pot of many different cultures and traditions that taken has root in this one part of the world. There’s many different varieties of gumbo and each form is influenced by different styles of cooking in the different regions. Even the gumbo cooked out in the bayou and river parishes is unique to this part of the world.

Israeli food is very similar in the sense that it is a melting pot of different cultures and cuisines and the way that it exists in Israel is different than the way it exists anywhere else in the world. It’s a place where Moroccans, Bulgarians, Yemenites, Turks, and Russians are all living together in the same place. They’re having children with each other and creating family traditions based off this melting pot of cultures. You don’t find that in other Middle Eastern countries or really anywhere else in the world.

Q: What influence does New Orleans and southern food have on your menu at Saba?

Shaya: It’s present on the menu when we talk about the resources that we use—like the shrimp and the okra. We don’t, for example, make an Israeli etouffee, or something like that. However, we do use the beautiful crab meat and shrimp and the chanterelles mushrooms that appear all over Louisiana in the summer. That’s the way we influence the menu with our local resources.

Q: What did you learn in Italy that impacts your approach to cooking today?

Shaya: I think that living and cooking in Italy helped me understand the importance of history, culture, and tradition in food in a way that I had never experienced before. Being in Italy you’re so completely embedded in this centuries-old tradition. Where I lived in Parma, prosciutto, Parmigiano Reggiano, anolini in brodo, and tortelli d’erbetta—all these dishes that haven’t gone anywhere and the locals eat them every single day. In the kitchens, I saw three generations of the same family working together. I was deeply influenced by that and I think it’s helped me develop the way I think about food and feeding people, and about being proud of the local resources that we have.

A great example is when a chef at the restaurant approaches me and says, “We already have a shrimp on this dish, so why should we have it on another dish?” And then I say, “Well, because we have some of the best shrimp in the world here in Louisiana and let’s just celebrate that.” If you’re in Apulia, Italy, every restaurant has burrata on the menu five different ways. It doesn’t just show up subtly, it’s there in abundance. And that’s because that’s where burrata comes from. Why would you shy away from that? You want to celebrate it.

Q: You spent a lot of time after Hurricane Katrina cooking red beans and rice for people in the community. What impact did that have on you?

Shaya: Hurricane Katrina changed so much for me. It really made me fall in love with New Orleans and Louisiana and claim it as my forever home. I felt like I could make a difference and be a part of something greater than just myself. I felt like I was a part of a community and could help it rebuild and learn from that experience. And I did. It helped me understand my values in a way that I had never really thought of before.

Q: I know community is important to you and you place a lot of emphasis on valuing each other and each one of your team members. Why you place such importance on that?

Shaya: My wife, Emily, and I started Pomegranate Hospitality in 2017 because we wanted to live out the values that were important to us every day and we didn’t feel like we were in a position to do that because we weren’t surrounded by the right people. I was able to have control over how to set up the business and the resources to really devote all our energy to that. And our director of people and culture at Pomegranate, Suzi Darre works all day long on sustaining a healthy culture and living up to the promises that we make to our team.

Q: Why is the Shaya Barnett Foundation important?

Shaya: As a teenager I was a misfit and just really lost. I was lucky to have Donna [Barnett; his home economics teacher] in my life to see my way forward. She recently retired from teaching and she was still so full of wisdom and energy. I wanted to work with her to try to make a difference in someone’s life the way she made in my life.

And that is our mission now. We’re doing that through our work with vocational programs, which have become very sparse in our country. So, in New Orleans and Denver we’ve partnered up with two vocational schools to help influence and inspire in any way that we can.

People are getting into this industry now that could be anything—astronauts, doctors, or scientists—and they’re choosing to be chefs because they love food and cooking. Our goal is to help people understand that and help guide kids that are wondering about the industry.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Moroccan Carrot Salad

yields 4–6 servings

Ingredients

- 2 lb carrots, no tops

- 1 tbsp plus ¼ cup extra-virgin olive oil, divided

- 1½ tsp Morton kosher salt, divided

- 2 tbsp apple cider vinegar

- 1½ tbsp Harissa (recipe below, can also be bought in local grocery stores)

- 1½ tsp sugar

- ½ tsp sweet paprika

- ¼ tsp ground caraway

- ¼ tsp ground cumin

- Zest of half of an orange

- Half of a yellow onion, thinly sliced

- 2 tbsp lightly packed fresh mint leaves

- Heat the oven to 400℉.

- Toss the carrots with 1 tbsp oil and 1 tsp salt and spread them over a rimmed baking sheet. Roast for 12–15 min, until they’re sweet and tender on the outside but still have that raw crunch in the center. Let cool to room temperature.

- In a large salad bowl, combine the remaining ¼ cup olive oil with the vinegar, harissa, sugar, spices, orange zest, and remaining ½ tsp salt. No need to worry about emulsifying. Thinly slice the onion and toss it in the dressing, then pile in the carrots. Tear the mint leaves over the salad just before serving.

Harissa

yields approximately 1 cup

Ingredients

- 15 dried árbol chile peppers

- 2 dried guajillo peppers (If you can’t find guajillo peppers, use 4 additional ancho peppers)

- 1 dried ancho chile pepper

- 1 tbsp whole cumin seeds

- 1½ tsp whole coriander seeds

- 2 large cloves garlic, crushed

- 2 tbsp lemon juice

- 1 tbsp white wine vinegar

- 1 tsp Morton kosher salt

- 1½ tsp smoked paprika

- 1 tbsp tomato paste

- ¾ cup olive oil, divided

- Fill a small saucepan with water and bring it to a boil. Add all the dried peppers and remove from heat. Cover and steep for at least 1 hour, or until the water has completely cooled.

- Strain the peppers and, with a paring knife, trim away the stems and split them lengthwise. Scrape away their seeds and any of the stringy pith inside—wearing latex gloves will keep your fingertips from burning. Be sure to get rid of them all or else it’ll be crazy spicy. Add to the bowl of a food processor and set aside.

- Toast the cumin and coriander in a small skillet over low heat, stirring occasionally, for about 3 min, until you start to smell them. Grind them in a mortar and pestle or chop them by hand to release all their aromas, then add the garlic and mash it all into a paste.

- In a food processor, combine the garlic and spices with the lemon juice, vinegar, salt, paprika, and tomato paste. Once everything is blitzed together, stream in ½ cup olive oil.

- Scrape the sauce into a container and stir in another ¼ cup of olive oil by hand. This last addition lingers on the surface and absorbs all the flavors around it. Harissa keeps for months in the fridge, and once you start using it, you’ll find it has a home on just about everything. With its smoky heat, it’s one of the best “hot sauces” around.