A Piña Colada Tastes Better on a (Virtual) Beach

During IFT19, an interactive event allowed participants to be immersed in a virtual environment to test whether their surroundings would alter their liking of beverages.

Article Content

The classic central location testing (CLT) paradigm is pervasive in consumer research and usually involves carefully controlled tests run in sensory booths specially designed to minimize any unnecessary stimulation or distraction. These booths limit extraneous factors that may impact participants’ perception or influence how they evaluate samples, including eliminating any context from their surroundings. However, in the real world, people do not consume foods or beverages under such isolated circumstances. Conducting sensory tests in plain and neutral booths can also give rise to another problem: The results that sensory scientists obtain can lose touch with the perception of those same stimuli in real-world conditions as was famously demonstrated with the failure of “new Coke” (Oliver 1986).

People have attempted to incorporate the external validity that arises from context in a number of ways. In one example, researchers used a mobile testing laboratory moved by a truck to introduce some realistic contextual elements to the test while maintaining reasonable control of sample preparation (Resurreccion 1998). Some scientists have reported directly creating the environment they wanted within a testing room, for example, a simulated airplane cabin (Holthuyesen et al. 2017). The results showed that a simulated context can have a similar effect to that of real context on food perception. Despite the ecological validity of these methods, they can be expensive and time-consuming, which precludes them from widespread adoption. Still, using less expensive measures, others have attempted to add environmental context via written descriptions, pictures, or videos. Currently, modern technologies such as virtual reality (VR) are drawing researchers’ attention as a potential solution to this problem (Jaeger and Porcherot 2017).

Sunshine Makes a Good Piña Colada

At the IFT19 annual event in New Orleans, more than 100 attendees, most of whom were food industry professionals, participated in the “Virtual Reality Tasting Experience.” These participants tasted nonalcoholic piña coladas and Bloody Marys while wearing a virtual reality headset displaying a 360-degree video of a sunny beach and tasted both drinks without the headset. They rated their liking for each drink on a nine-point hedonic scale in real time. At the end of the test, the participants completed a survey that contained questions about 1) the frequency of their consumption of the two drinks, 2) VR (e.g., their familiarity with VR, their perceived level of immersion, whether they experienced dizziness, how useful they perceived this type of testing, and other implications), 3) demographics, and 4) their thoughts about this approach. The main goal was to determine whether simply viewing and hearing a beach setting via the VR headset could alter people’s perception. If so, then the beach setting would increase people’s liking for piña coladas, which are commonly consumed on beach vacations, whereas ratings for Bloody Marys would not be affected significantly.

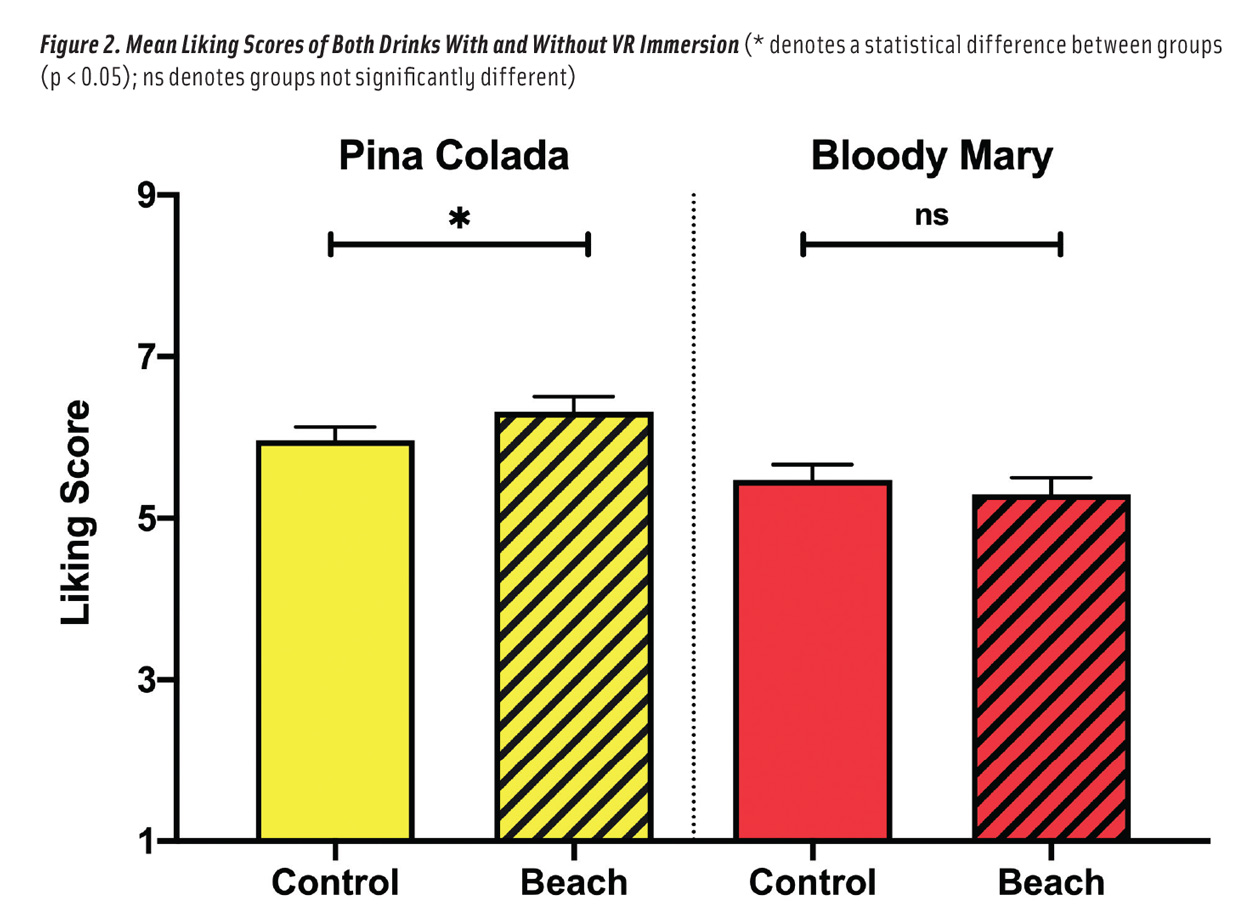

Indeed, the VR test data indicated statistically higher liking scores when the participants consumed piña coladas on a virtual beach than they did when tasting without the VR headset. The mean liking score for piña coladas increased from a 6 to a 6.3 with a VR beach scene; the liking scores for Bloody Marys remained the same under both conditions. The results didn’t seem to simply be a feature of wearing the VR headset as the tasters’ liking for Bloody Marys wasn’t altered with or without a virtual beach. Additionally, many participants described the Bloody Marys as “odd,” “improper,” or “weird” in the virtual beach context. This suggests that associations exist between certain experiences and flavors: Few people associate a Bloody Mary with being on vacation, but many people associate a piña colada with a relaxing vacation on a beach. However, some panelists still rated samples atypically by liking Bloody Marys more on the beach. Clearly, how people are influenced by context is subject to their personal experiences and habits. Further investigation of such relationships could help sensory scientists understand when people most enjoy a particular food or drink and might even hint at why people adopt unhealthy eating practices in certain situations.

Bloody Marys Aren’t for Everyone

Though there were no effects of VR on liking of the Bloody Mary, the frequency at which participants consumed them in their usual lives did show an influence on liking. Those who identified as habitual consumers of Bloody Marys liked them statistically more than those who do not drink Bloody Marys regularly (as might be expected). Nearly half of the participants indicated that they had never drunk a Bloody Mary before, and because their mean liking score was just slightly above a 5 (i.e., neutral), this implies they may never drink one again. This pattern was not observed for those who had never drunk a piña colada—probably because a piña colada is a sweet, creamy drink and thus much easier-going for a novice. A Bloody Mary is clearly not a drink for beginners.

VR Immersion

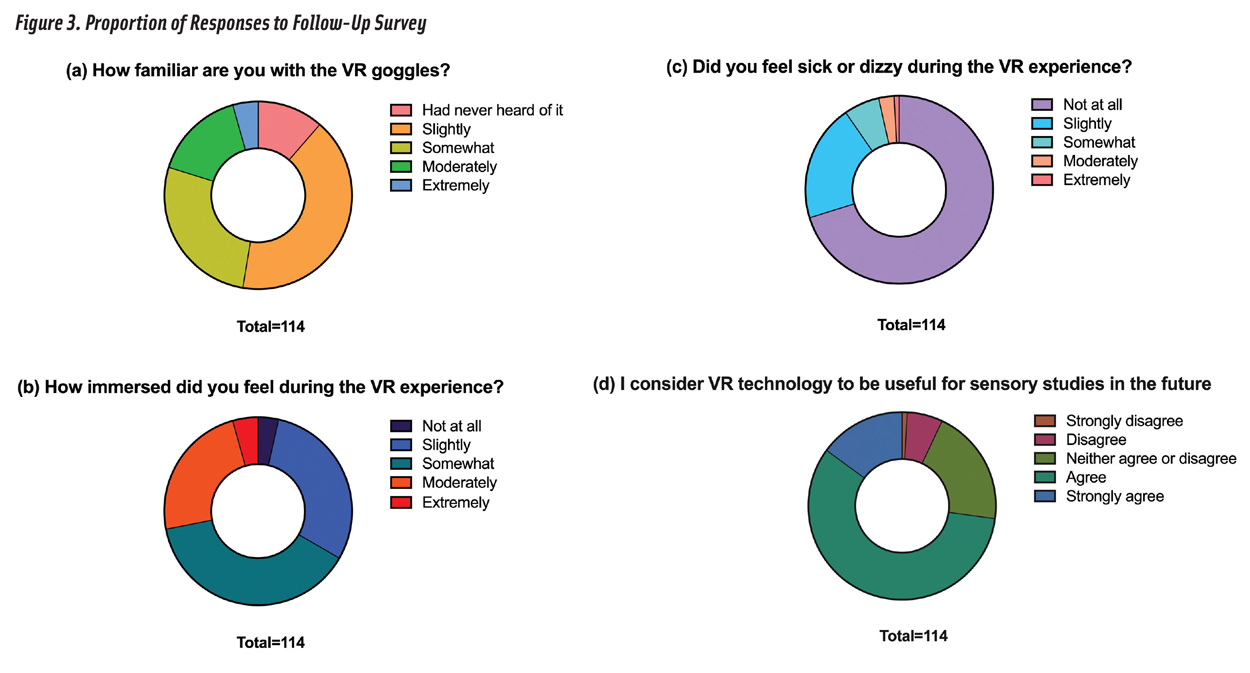

Panelists’ familiarity with VR varied from extremely familiar to not having heard of VR at all. Almost half of them reported more than “slight” familiarity; however, 11% of them had never heard of this technology before the event. More than 96% of participants said they felt some degree of immersion during the experience. The panelists’ degree of immersion was influenced by their familiarity with VR. With increasing familiarity, the feeling of immersion participants perceived increased, possibly due to the more fluid experience that results from understanding the controls and mechanics of a VR system. It is thus likely that a longer training period in which panelists learn how to use the technology may elicit a more immersive end result. Ratings of immersion were not impacted by whether a panelist felt any sickness or dizziness during the experience. Most panelists (70%) did not feel any sickness or dizziness at all; however, a number of panelists reported slight dizziness. Also, there was no correlation between liking scores for the drinks and reported levels of dizziness.

Participants also indicated their attitude toward applying VR technology in future sensory studies via a Likert scale. More than two-thirds of participants (73%) believed this technology would be useful in the future. First-timers saw the most potential for VR in sensory studies in the future, possibly also reflecting the novelty of the first exposure to VR. Other significant predictors of a panelist’s perceived usefulness of VR in sensory were the panelist’s perceived level of immersion when wearing the headset and their age: Younger participants were more likely to accept VR as a useful tool for sensory.

Areas for Improvement

In response to a question on the usefulness of VR, there were several constructive comments. Six percent of participants referenced some form of incompatibility; for example, some said that the headsets did not fit well with glasses or that it was hard to taste the samples with the headsets on. Only 3% worried about the headset’s pressure on their nostrils whereas 23% noted that the weight of the headsets made them a little uncomfortable. The blurriness of the picture was the most notable issue reported: 41% of panelists perceived the video as having a low resolution. This can be easily remedied as many VR headsets with higher resolution are available; the system used in this experiment was made purposefully with cost in mind, containing a full setup and four headsets costing under $1,000 (Stelick et al. 2018). Finally, several panelists suggested testing in a quieter environment or using a higher volume to add to the degree of immersion. This can also be easily remedied in a real testing situation as most testing environments would not be in the expo hall of an IFT annual event.

Peiyuan Zhou, a member of IFT, is a doctoral student at Cornell University ([email protected]).

Mingze Qin, a member of IFT, is a master’s student at Cornell University ([email protected]).

Robin Dando, PhD, a member of IFT, is an associate professor at Cornell University ([email protected]).

Megan Barenie and IFT volunteers assisted in carrying out the VR testing project.

REFERENCES

Holthuyesen, N. T. E., M. N. Vrijhof, R. A. de Wijk, and S. Kremer. 2017. “Welcome on board:” Overall liking and just-about-right ratings of airplane meals in three different consumption contexts—laboratory, re-created airplane, and actual airplane. J. Sens. Stud. 32(2): 1–8.

Jaeger, S. R. and C. Porcherot. 2017. Consumption context in consumer research: Methodological perspectives. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 15: 30–37.

Oliver, T. 1986. The Real Coke, the Real Story, New York: Random House.

Resurreccion, A. V. 1998. Consumer Sensory Testing for Product Development. Gaithersburg, Md.: Aspen Publishers.

Stelick A., A.G. Penano, A.C. Riak, R. Dando. 2018. Dynamic context sensory testing–A proof of concept study bringing virtual reality to the sensory booth. J. Food Sci. 83(8): 2047–2051.