Playing the open dating Game

The authors use a baseball analogy to stress that a federally mandated open dating system can increase efficiency and understanding among retailers and their customers

PRE-GAME STATS

94% of shoppers have noticed it, 75% claim to have used it to make a purchase, but less than 50% even understand its meaning. What is it?

The answer to this question (Sherlock et al., 1991) is, of course, an “open date” or “open shelf-life date” on a food product. An open date refers to the date on packaged food that indicates when the product was packed, meant to be “sold by,” or meant to be “used by.” Such a practice has been in demand since the beginning of the 20th century.

Just as with most games, open dating involves rules and regulations, defenders and opponents, and the potential to become a stronger presence in the league (of supermarket practices).

Dating of food products has been known to exist in the dairy industry since 1917 (Anonymous, 1979). As America continued to urbanize, the use of processed foods purchased through grocery stores increased. Consumer Reports, dating back to the 1930s, reported consumers’ desires for an open dating regulation to indicate the freshness of their foods, and some supermarket chains began implementing some type of system in the early 1970s (Seligsohn, 1979). During 1979–80, although the Food and Drug Administration had yet to propose any federally required open dating regulations, a number of consumers, processors, and consumerist groups held hearings discussing its possible future implementations (IFT, 1981).

Within the past three decades, there have been several extensive surveys on open dating, and research on open dating has increased. These surveys have indicated a consumer demand for open dating regulations. For example, an A.C. Nielsen Co. (1973) report stated that many people looked on the food packages for some type of date to aid them in selecting the freshest food. At that time, as is also true now, many manufacturers preferred using code dates. The purpose of a code date was to assist supermarket employees with stock rotation and as a means of lot identification in the case of product recalls. Although the everyday use of code dates was not directly intended for the consumers’ benefit, a consumer group, the New York State Consumer Protection Board, published a book deciphering the meanings of the manufacturers’ code dates. They received more than 100,000 orders for this code book in the first year alone (IFT, 1981), although the book does not exist today. Some supermarkets at that time actually put several books in their stores so consumers could decipher the code dates on food products while they shopped.

The U.S. Dept. of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service (ERS) and the Consumer Research Institute conducted a consumer survey in 1973 concerning food spoilage (USDA, 1973). The results showed a lack of consumer confidence in the products they had purchased from the supermarket. While 93% of the people surveyed reported that they had not purchased any stale or spoiled products within the past year, many of them indicated a problem with the freshness of foods. Within the two weeks prior to being surveyed, 18% of the customers purchased food which spoiled or staled before they expected. When a food was spoiled on the day that it was purchased, most consumers reported that they threw the product out rather than returning it to the store—in spite of the fact that 62% of the shoppers knew about the store’s money-back guarantee.

FDA conducted its own survey in 1973 concerning open dating and published the results in the Federal Register (FDA, 1979). This led to a federally sponsored project by the Office of Technology Assessment to determine if such dating needed federal regulation (OTA, 1979). After surveying 1,374 grocery shoppers, FDA reported that 94% of the shoppers claimed that they had noticed the dating on various food products; about 75% of those shoppers claimed to have used the date in making a purchase (Labuza, 1982). In 1981, the Institute of Food Technologists’ Expert Panel on Food Safety and Nutrition published a scientific status summary titled “Shelf-Life Dating of Foods” to inform professionals about open dating (IFT, 1981).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

For about 18 years, open dating concerns seemed to have disappeared, but the issue became hot again around 1996. For example, a study by Supermarket News indicated that peak freshness was the most important quality consumers looked for when shopping for perishable foods (Dowdell, 1996). In fact, fresh products in the meat department were the most important factor in determining where 73.6% of the surveyed consumers shopped (Stickel, 1996). In addition, when consumers saw a “sell-by date” on a food product, it heightened their confidence about the food’s freshness (Dowdell, 1996). Although an open-date system does not guarantee the consumer that a food product is not spoiled, as would happen if it was improperly handled, a date can be used as an indication of freshness.

Other research indicated that to increase effective communications with the consumer, simple and basic information works best. According to Joanne Gage, Vice President of Consumer and Marketing Services at Price Chopper Supermarkets, Schenectady, N.Y., the “sellby” or “use-by” dates on precut packaged items, like fresh-cut salads, are the information most sought after by the consumer (Williams, 1998).

A recent outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes foodborne illness caused 21 deaths (15 adults and 6 miscarriages/stillbirths) across the nation (CDC, 1999). The source of the foodborne illness was from ready-to-eat meat products, such as hot dogs and luncheon meats, consumed very close to the stamped “use-by” dates. If the products were temperature abused, however, conditions may have allowed the pathogen to reach an infectious dose before the end of other food quality attributes, as was inferred by Thomas Billy, head of USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service, FSIS (Silverman, 1999). While food regulators scramble to determine the breakdowns in food safety, they already know that federal rules governing how the “sell-by” and “pull-by” dates are determined on packaged foods is a major part of the solution (Anonymous, 1999).

THE RULES

Who regulates the present open dating requirements? a. Federal government b. State legislation c. Industry standards d. Nobody

The answer to this question is quite complex. Other than prescription and over-the-counter drugs and infant formula, which are federally mandated by FDA to have a date, the open date on food products is generally established by the food industry to indicate a product’s shelf life (Fig. 1). Shelf life can be best represented as the end of consumer quality, as determined by the percentage of consumers who are displeased by the product (Labuza and Schmidl, 1988). This definition accounts for the variation in consumer perception of quality and has an economic part; i.e., since it is not possible to please all consumers all of the time, one must establish a baseline of consumer dissatisfaction.

The answer to this question is quite complex. Other than prescription and over-the-counter drugs and infant formula, which are federally mandated by FDA to have a date, the open date on food products is generally established by the food industry to indicate a product’s shelf life (Fig. 1). Shelf life can be best represented as the end of consumer quality, as determined by the percentage of consumers who are displeased by the product (Labuza and Schmidl, 1988). This definition accounts for the variation in consumer perception of quality and has an economic part; i.e., since it is not possible to please all consumers all of the time, one must establish a baseline of consumer dissatisfaction.

An article in Supermarket News in 1997 stated that an increase in consumer pressure and media attention have strengthened the overall awareness of infant formula dating (Moore, 1997). Depending on the volume of sales in a store, employees should be restocking these products on a daily to weekly basis and supposedly checking the expiration dates each time. According to the article, however, infant formula within days before its expiration date was discovered on grocery store shelves. There is no law regulating how far in advance of their expiration dates products must be removed from the shelves, but most chains claimed to remove the products within a month beforehand.

Meat and poultry products are under the federal control of FSIS. A retailer may sell meat and poultry products that are wholesome even if they have gone beyond the expiration date on the label. However, there is virtually no way one can determine wholesomeness for most prepackaged products. Thus, the potential for disaster is a constant threat. It is illegal for retailers to alter, change, or cover up the expired date with a new date if the meat was federally inspected; however, if the meat is cut and wrapped at the store, the label can be changed (FSIS, 1995).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

In a recent case, a Sainsbury store (a large supermarket chain in the United Kingdom) was charged for unethical open dating practices and fined $14,000 for selling foods past its “use by” dates and trying to conceal the original open date with a new sticker. The food items included crab, beef burgers, ostrich goujons, and chocolate roulade. The issue was brought to the attention of the authorities by a consumer who noticed the October 29 “use by” label on the crab meat that he purchased covering another label stating October 27 as the use-by date. The Sainsbury store admitted to the offense, but they stressed that all of the products would have been safe to eat and would not have invoked any potential threats (Butler, 1998). This may or may not be true, but safety is not the key point of open dating; this defense only confuses the matter.

In another example (Besfamille, 1998), the “Direction Generale de la Concommation et de la Repression des Fraude,” the French public agency in charge of the quality of goods sold to the consumer, found 115 cases of relabeling of out-of-date meat during 1,200 inspections at the grocery store level. In France, meat must have a use-by date which is set discretionally by the seller. Although no cases of seizures by U.S. or state authorities have been reported in the legal literature, it is commonly felt by the consumer that this practice also occurs in the U.S.

According to Labuza and Szybist (1999), the District of Columbia and 29 states mandate some sort of open dating policies on foods. These policies are regulated by various state departments, depending on the state, such as the Department of Agriculture, Department of Weights and Measures, Department of Public Health, etc. In 1979, the Grocery Manufacturers of America took the Massachusetts Department of Public Health to court to overthrow the state’s proposed open dating requirements on all foods because of the burden it posed to interstate commerce (GMA v. Massachusetts, 393 NE 2d, 881, 1979). The Supreme Court of Massachusetts, however, ruled that the T legislation “bore reasonable relation to [sic] goal of consumer protection” because out-of-date products have an increased risk of containing non-safe agents. Not providing a date on a food product was an omission of fact and was therefore considered misbranding.

Open dating of all food products is mandated in many countries, including the countries of the European Union, many South American countries, many of the Arabic States, the Scandinavian countries, Israel, and Taiwan. Within the EU legislation, for example, open dating (or durability dating) was amended in Directive 97/4/EEC of the European Parliament and of the Council. Article 9 of this directive mandates the use of “Best before” and “Use by” dates. Uniform legislation among the EU members will simplify food regulations across the continent’s borders. It will also allow the European people to understand the dates on their food products in any supermarket chain in any country of the EU. This increased confidence in an open dating system is a luxury yet to be afforded by the American people across this country’s state borders.

HOME TEAM PLAYERS

On the retail level, who are the benefactors of an open date system? a. Retailers b. Consumers c. Both a and b d. None of the above

The answer to this question is c. An efficient open dating system would play a synergistic role with increased effectiveness in the supermarket industry, in particular, with respect to Efficient Consumer Response (ECR), a joint task force developed in 1992 by grocery retailers, distributors, suppliers, and brokers to increase the competitive edge in the grocery industry. While looking at current practices in the industry, the overall goal of this approach was to create potential opportunities in the grocery business and raise customers’ satisfaction without a huge financial burden. It included computerizing restocking procedures and just-in-time delivery.

While implementing ECR will mainly require the reorganization of the internal and external structures of the grocery supply chain and changes in communication among those sectors involved, an efficient open dating system fits directly into the guidelines of this approach. Principle 1 of the “Guiding Principles of Efficient Consumer Response”(Kurt Salmon Associates, 1993) is “Constantly focus on providing better value to the grocery consumer: better product, better quality, better assortment, better in-stock service, better convenience with less cost throughout the total chain.”

--- PAGE BREAK ---

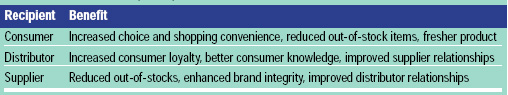

An efficient open dating system would actually enhance the ECR system and increase its benefits to the store. The intangible benefits of ECR for the consumer, distributor, and supplier are listed in Table 1. Many of the benefits of ECR also mirror the benefits of open dating (Kurt Salmon Associates, 1993).

An efficient open dating system would actually enhance the ECR system and increase its benefits to the store. The intangible benefits of ECR for the consumer, distributor, and supplier are listed in Table 1. Many of the benefits of ECR also mirror the benefits of open dating (Kurt Salmon Associates, 1993).

Stock control is another important issue for retailers that usually involves open dating. With thousands of different code dates being used by the food industry, it is unreasonable to expect food distributors and supermarket employees to be able to decipher every one of them. In 1972, Keith Ford of the Minnesota Office of Consumer Services found that 44% of the infant formula they observed were over age. An astounding 64% of the store managers could not read the date codes on the products; therefore, they were not rotating the stock to allow for selling of the oldest product (Labuza, 1982). In addition, of the 25 stores surveyed, 100% had out-of-date products on the shelves.

The recent policy change by the Procter & Gamble Co. may increase retailers’ need for understanding code dates. The company will no longer be responsible for goods that the retailers cannot sell, including those items with limited shelf life. Instead, P&G will pay lump sums to retailers on a quarterly basis to cover the cost of old or damaged goods. As Narisetti (1997) wrote, “It’s likely that P&G’s payment plan will seem like a bonus to efficient retailers and prove costly for those with poor ordering or handling systems.” Other companies are expected to follow P&G’s lead. If other food industries begin to implement the P&G practice, there will be an increased need for a legible open date printed on prepackaged food, which would improve inventory control (IFT, 1981). Readable dates not only assist supermarket personnel in stock rotation but also lessen the chances of a consumer’s purchasing foods of lower quality (Anonymous, 1979).

Issues such as food safety and quality, nutrition, and educational value also benefit the retailers as well as the consumer:

• Food Safety and Quality. An efficient open dating system may heighten awareness along the distribution chain. As previously mentioned, the open date can be used as a guide to ensure “first-in, first-out” practices (stock control). Proper handling and storage of food products also are necessary to produce the highest standards in food quality and ensure food safety. With controlled temperatures and humidity levels, proper rotation practices, and monitored home storage conditions, food quality and the safety of foods will be enhanced (Taoukis et al., 1997).

Food quality can refer to perceived freshness or sensory changes such as color, odor, flavor, and texture of the food product that lead to consumer dissatisfaction. It may also imply functional properties. Some foods, such as baking yeast, lose their functional properties over time (Anonymous, 1971). Open dating of such foods is necessary. In addition, pre-emulsified salad dressings will separate if temperature abused, and raw eggs will lose part of their whipping functionality after 30 days of storage.

An in-store experiment conducted by USDA supported the concept of increased consumer confidence in food quality when open dating was introduced (OTA, 1979). With regard to foods commonly cited for spoilage or staleness, such incidence complaints at the experimental store were reduced by 50% after open dating was implemented. The store also experienced decreased financial losses and package rehandling. The spoilage complaints decreased for both the open-dated and non-open-dated products at the store. Although the open dating system did not reduce food spoilage, it may have attributed to the consumers’ increased confidence in the overall freshness and food quality of the food products sold at that store.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

• Nutrition. Environmental conditions leading to nutrient losses are identical to those factors affecting loss of quality. Open dating assists as well as forces more precise distribution practices, so products can reach store shelves before nutritional degradation occurs. An increased awareness could decrease the losses of several vitamins (such as A, B, and C) and some essential amino acids (IFT, 1981). Under normal conditions, the open date will indicate when the nutrient loss is significant and the nutrient level goes below the legal level stated on the label for the most labile nutrient, e.g., vitamin C in refrigerated orange juice.

• Educational Value. The educational value associated with open dating is significant, as it may affect consumers’ purchasing habits. In FDA’s (1979) survey, only 1.3% of the participants responded that they were confused about what the date on food products represented. Further questioning, however, revealed that most of the respondents actually did not know what the date meant. With an increased understanding about the time period of a food’s acceptable quality, a trust will form among the consumers, food store personnel, and the food industry (IFT, 1981).

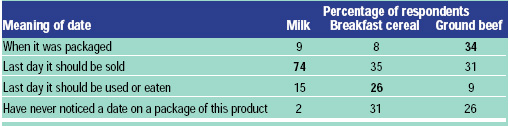

The OTA (1979) study assessed consumers’ understanding of open dates (Table 2). The results were mixed as to what the participants understood the date to mean on milk, breakfast cereal, and ground beef packages. Interestingly, about three-quarters of the shoppers correctly identified the date on milk; only one-quarter of the answers for breakfast cereal and one-third of the answers for ground beef were accurate.

The OTA (1979) study assessed consumers’ understanding of open dates (Table 2). The results were mixed as to what the participants understood the date to mean on milk, breakfast cereal, and ground beef packages. Interestingly, about three-quarters of the shoppers correctly identified the date on milk; only one-quarter of the answers for breakfast cereal and one-third of the answers for ground beef were accurate.

A later study conducted by the Minnesota/South Dakota Dairy Research Center in 1992 confirmed that this misunderstanding continued. Sherlock and Labuza (1992) reported that 94% of the people in that survey stated that the date label was extremely important in the purchase of milk. However, about 25% of those surveyed doubted the reliability of the date, while 61% of the participants claimed that they did not even understand the date.

Based on this information, a uniform open dating system at the federal level would help to decrease consumers’ confusion and build their confidence in product freshness. It would also force the industry to improve its control over product quality through distribution, including better control during holding in the supermarket (Anonymous, 1979). Also, with consumers’ understanding that an open dating system is only an indication of freshness and that the date written on the product is not necessarily the end of product quality, it may lead to a reduction in food waste.

THE OPPOSING TEAM

True or False: Open dating is not a flawless practice.

Open dating is not a perfect system, and not everyone is in favor of a mandatory open dating system. Drawbacks of an open dating system may include its lack of food safety protection as well as the expense.

Concerning food safety, an open date cannot prevent failures during or after processing or improper practices in the distribution chain (IFT, 1981). As stated in a University of Minnesota study on food shelf-life indicators, “If the food is temperature abused, an open date is meaningless and in fact is a false sense of security” (Taoukis et al., 1991). In other words, an open dating system would provide little or no help in detecting pathogenic microbial levels in abused food products (IFT, 1981).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

The financial aspects of implementing open dates are also a necessary consideration. In 1979, experts were consulted to discuss the costs of open dating at the request of OTA, which was the research branch of Congress headed by Senator Ted Kennedy (Chair of the Committee). This group comprised consumer representatives, food retailers, processors, wholesalers, scientific experts, and state and federal government officials (OTA, 1979). The following issues were investigated concerning cost: establishing shelf life, dating the package, and enforcement.

One of the cons about implementing a mandatory open dating system is the financial cost for implementing shelf-life testing. In 1979, the cost for a perishable food product was estimated to be approximately $100,000, and the cost for a non-perishable product was about $200,000 per food item tested. Obviously, the costs would be higher 20 years later. Enforcement costs would be difficult to estimate without knowing the enforcement system needed to be implemented. One option would be a self-enforcing system, where there are no penalties for out-of-date products. Instead, customers would enforce the open dating system by refusing to pay full price for such items. If legal penalties were to be enforced, the cost would be high.

From the supermarket standpoint, the costs of implementing a stock-rotation policy to prevent people from sorting for the freshest date would be costly and might increase food waste. Dairy and bakery products are two of the largest contributors to food loss because products which are still safe to eat and of acceptable quality are often removed from supermarket shelves once they reach the sell-by date. In the U.S., an incredible amount of food is wasted each day. According to USDA, 5.4 billion lb of food was estimated to be wasted in 1995 at the retail level, and 91 billion lb was lost at the foodservice and home level (Kantor et al., 1997). Milk, for example, is a highly perishable product, and it was estimated that almost 27% was wasted in the distribution system in 1995 in part because of spoilage (Kantor et al., 1997). In a 1971 study, 62% of 628 people surveyed stated that they sometimes sort through packages to find the freshest product. From that same group, 74% claimed that while sorting through dated products (Fig. 2), they would usually find some products that were fresher than others (Anonymous, 1971).

FOUL BALLS

What is the most inhibiting factor that makes the dating of refrigerated foods a questionable practice? a. Temperature abuse b. Temperature abuse c. Temperature abuse

As mentioned by the opposition with regard to open dating, temperature abuse will affect the usefulness of an open date while presenting a potential threat to the consumer. According to Labuza (1982), “Shelf-life is not a function of time alone, rather it is a function of the environmental conditions and the amount of quality change that can be allowed.” The “environmental conditions” often relate to the temperature of food products during storage and distribution.

The maximum temperature recommended for chilled foods in warehouses, trucks, and retail displays by the National Food Processors Association is 40ºF. NFPA has also published the following information for the optimum temperature ranges of various chilled food products during distribution and storage: dairy products 32–40ºF, meat 30–34ºF, poultry 30–34ºF, seafood 30–34ºF, and salads 32–40ºF (Brody, 1997). In its revised Food Code (1997), FDA established 41ºF as the recommended maximum temperature for retail establishments which handle meat, fish, poultry, delicatessen products, and precut produce (Brody, 1997).

Unfortunately, whether because of carelessness or expense, current practices do not always meet with the recommendations. Besides the possible expense of having to employ new technology to maintain proper temperatures, retailers and distributors face the fact that there is a 10% increase in total energy costs for every 5ºF decrease in refrigeration temperature (FNQEB, 1999). The economic costs should not supersede the boundaries of safety, but studies show that the proper steps in temperature control are not being taken seriously.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

An Audits International (1990) survey reported startling results after temperature measurements were recorded of 1,000 refrigerated food items at three points: at the retail level, when the products reached the consumers’ homes, and after 24 hr in the home. Delicatessens in the study had refrigerated foods stored at temperatures ranging from 34 to 71ºF, with an average of 47ºF. The average home refrigeration was 43ºF. Both of these averages are above the 40–41ºF recommended for refrigerated food, meat, poultry, and eggs. Almost 10 years later, Richard Daniels of Audits International reported a followup study at the International Fresh Cut Produce Conference in San Diego (Anonymous, 1998). In a sample of 98 supermarkets, the mean temperature in the refrigerated deli case was 46ºF, with 10% of them at a mean of 58ºF. In the produce section, packaged salads were also at a mean of 46ºF. In both cases, this will cause more rapid deterioration of prepackaged foods and could also lead to a safety issue.

A study sponsored by The Refrigeration Research and Education Foundation found that approximately 20% of retail chilled display cabinets operated at temperatures above 50ºF and that more than two-thirds of the chilled food retailers did not monitor the expiration dates on the products (Brody, 1997). These studies illustrate a potential for growth of pathogens that might cause food poisoning, especially in abused chilled food products that are minimally processed. At temperatures above 40ºF, pathogenic anaerobic microorganisms are capable of growth and toxin production. Between 40 and 55ºF, nonproteolytic anaerobic microorganisms may grow. Such spoilage is not detectable by smell (Brody, 1998).

Those groups most susceptible to food poisoning include the elderly, the young, immunocompromised individuals, and pregnant women. The group with the highest risk of mortality from food poisoning, however, is the elderly. A study by Angela Johnson of the University of Nottingham, England, looked at the food safety knowledge and ractices of elderly people living at home (Johnson et al., 1998). While the participants’ overall understanding of the “sell by” and “use by” dates was decent, 45% of them could not read the dates because of poor eyesight and small and hard-to-read print. Of even greater concern, however, was the fact that 70% of the participants’ refrigerators were too warm to safely store food.

An open date will not protect consumers from microbial threats, but it can be useful as a guide. If the product is kept at ideal temperatures and conditions throughout its life span and is consumed before the end of shelf life, then the food will most likely be safe. The September 1998 issue of Newsweek mentioned that to guarantee that temperature abuse has not occurred, “tell the truth” tape or time–temperature integrators (TTIs) are being designed to signal a premature end of shelf life (Springen, 1998). The TTIs are mentioned in greater detail in a following section. After consumers check the TTI, they will feel confident that their product has not been temperature abused, and with an open date they will know approximately how long the product will remain fresh under proper conditions. Such information may be useful at both the retail and consumer levels, since many consumers may not be aware of the actual storage conditions in their own homes (Taoukis et al., 1991).

Studies done by Tropicana Products, Inc., illustrated the effects of temperature abuse on their products (Kalish, 1991). In the 1980s, the company discovered that 72% of the consumer complaints on chilled juices were connected with temperature abuse. When examining this problem, the company found that the temperatures during the distribution of the juice reached 45ºF in some cases. The recommended temperature range for proper storage of the juice is 32–38ºF to maintain high quality. Within the retail stores, only 37% of the products were stored at the proper temperature. During storage, the average temperature of the juice was about 44ºF and went as high as 56ºF. The rotation practices in the display cabinets were also found to be poor.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Tropicana also conducted a time–temperature experiment measuring the flavor quality. The juice was rated on a scale of 1 to 9, with scores below 5 being unacceptable. The results showed dramatic differences in quality with temperatures only 10ºF different. These changes in the shelf life as a function of time and temperature are a function of the product’s temperature sensitivity factor Q10. Juice held at 45ºF fell to a 5.1 score after only 49 days, while juice held at 35ºF, i.e., 10ºF lower, remained above 6.0 for the entire 63-day shelf life (Kalish, 1991).

Lack of temperature control is not just a problem in the food distribution chain. Bishai et al. (1992) found that of 50 pediatric clinics in the Los Angeles area, only 16% of vaccine (measles, mumps, rubella) storage coordinators could cite appropriate storage temperatures for vaccines, and 18% were not even aware that temperature abuse would destroy the effectiveness. Refrigerator thermometers were checked once weekly in only 20% of the offices, 22% of the refrigerators were above the recommended temperature range, and 16% of the offices stored vaccine unrefrigerated.

TIME OUT!

The open dating game is now being played, but it’s time to call a “time-out” and evaluate our current play. The stats show that changes need to be made.

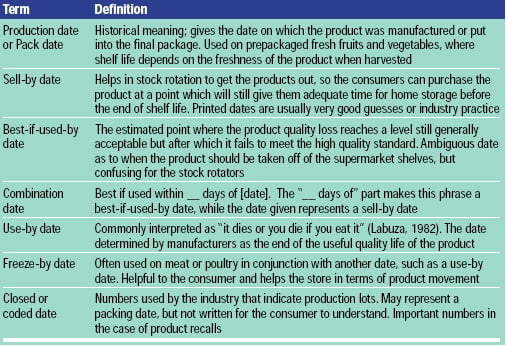

Before looking at the open dating practices currently being implemented, it is important to understand exactly what these dates represent. Table 3 defines the basic open dating terminology.

Before looking at the open dating practices currently being implemented, it is important to understand exactly what these dates represent. Table 3 defines the basic open dating terminology.

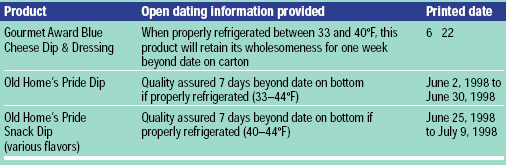

We collected current data on open dating practices in a large supermarket on the outskirts of St. Paul, Minn. The information collected included “Name of Product,” “Company Name and Address,” “Dating System,” the actual “Date” written on the package, and any “Additional Comments” related to the open date system. Table 4 illustrates some of the different explanatory phrases for open dating found on flavored dips and yogurt taken in this study.

It is interesting to note the temperature ranges given for storage of the products. On Old Home’s Pride dips (various flavors), the temperature range on the labels spanned more than 11ºF. The products’ change in quality as a function of temperature would be significant, and there would be a significant difference in shelf life, as was seen with the Tropicana products mentioned above. Therefore, if two containers of dip are dated June 2, and one is held at 33ºF while the other is held at 44ºF, the former product will actually have a longer shelf life than its identical product stored at a higher temperature, perhaps as much as twice as long.

It is interesting to note the temperature ranges given for storage of the products. On Old Home’s Pride dips (various flavors), the temperature range on the labels spanned more than 11ºF. The products’ change in quality as a function of temperature would be significant, and there would be a significant difference in shelf life, as was seen with the Tropicana products mentioned above. Therefore, if two containers of dip are dated June 2, and one is held at 33ºF while the other is held at 44ºF, the former product will actually have a longer shelf life than its identical product stored at a higher temperature, perhaps as much as twice as long.

Depending on the characteristics of a food product, potential forms of food deterioration are important factors to consider when establishing an open date and managing the distribution, including holding practices at the supermarket level. The food’s primary mode of deterioration will depend on a variety of characteristics: food composition, chemical constituents, enzymatic activity, processing technique, packaging used, and distribution. In some cases, the process of deterioration may be prolonged by manipulations by the food industry or proper handling techniques by grocers and consumers.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

PINCH HITTER

Despite distribution and storage obstacles, what can be used with the open date to guarantee the freshest and highest-quality food and prevent “foul balls” (temperature abuse of refrigerated products)?

The OTA (1979) study concluded that the industry did not have the data at that time to properly implement an efficient open dating practice. A significant problem with open dating is that the loss of quality and “freshness” is not solely a function of time, but depends on the control of temperature, humidity, and light during distribution. Both the kinetics of deterioration and the product’s history of exposure, including temperature abuse, must be incorporated into the setting of a shelf-life date (Labuza, 1982; Taoukis et al., 1997).

As previously mentioned, however, TTIs used together with an open date form an undefeatable combination when properly implemented. TTIs are small devices that are placed on the food package to measure the temperature history of a product and indicate a definitive change at the end of shelf life. Through “integration” of the time–temperature exposure, TTIs are reliable indicators of end of shelf life for food products if they have temperature sensitivities similar to those of the deterioration mechanism (Taoukis et al., 1991). Because the devices are used on individual consumer packages, they establish a control system, since not all products will receive uniform handling, distribution, and time–temperature effects (Taoukis et al., 1991). Therefore, TTIs can increase the effectiveness of quality control in distribution, stock-rotation practices of perishable foods in grocery stores, and efficiency in measuring freshness by the consumer (Sherlock and Labuza, 1992).

Taoukis and Labuza (1989a, b) showed that for the most part, the commercially available TTIs are both reliable and applicable for use in combination with open dating of refrigerated foods. Malcata (1990) showed that although the tags respond more quickly to temperature abuse than the actual food, the response is on the conservative side of safety—i.e., the tag color indicates end of shelf life before the food is actually spoiled. The Campden Food and Drink Association in the United Kingdom has developed technical standards for evaluation of TTIs (Campden, 1992).

The three major manufacturers of TTIs are 3M, Lifelines, and Cox Recorders, Inc. As early as 1988, Find/SVP, a marketing consulting firm, concluded that the use of TTIs had great potential for use in the food business (Find/SVP, 1988). Although studies have shown that consumers believe in the validity of an open date and freshness, a survey by Business Marketing Research Inc. found that consumers would prefer clear, consumer-readable indicators of time and temperature to measure the freshness and safety of their perishable food products (Sherlock and Labuza, 1992).

The use of TTIs on dairy products has been extensively studied. As early as 1982 (Mistry and Kosikowski, 1983), the 3M and i-Point products were found to be very effective, making “it possible to replace the sell-by date on market milk.” Concerning the effectiveness of TTIs and the dairy industry, a study by Duyvesteyn (1997) concluded that “Although the tags did not sufficiently predict the sensory endpoint it is still thought that tags would be beneficial to the dairy industry when used along with a ‘Use-by date.’” Duyvesteyn focused on the reliability of the TTIs, but its use in conjunction with a “use-by” date will not be effective if there are no standards for determining a proper date.

An open date may be used to indicate a problem with distribution if the TTI expires much faster than the printed date. Quickly identifying such a problem can decrease the food waste in this country. According to observations made in this study, on November 25, 1997, the “sell-by” dates on milk containers at a local grocery store ranged from November 28 to December 12. In this case, the “sell-by” dates on the milk products are useful in determining whether the product should be sold within 3 days or 17 days to still maintain a reasonable time before reaching the end of shelf life at home. In most cases, the open date could be extended if the milk product is constantly handled under the proper temperature.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

On the other hand, an open dating system may actually contribute to the larger milk waste every year. To eliminate some of this waste, the open date could be used as a guide to end of shelf life, but TTIs would be more effective in this case to determine the actual time of the products’ unacceptability.

Besides consumer acceptance and food waste reduction, TTIs may play a critical role in food safety. There are potential dangers of controlled-atmosphere/ modified-atmosphere-packaged (CAP/MAP) prepared meals with temperature abuse. Improper conditions can lead to the growth of harmful pathogens such as Clostridium botulinum, Listeria monocytogenes, and Salmonella enteritidis. In one reported case, four people became ill from C. botulinum (a potentially lethal pathogen) from a CAP/MAP shredded cabbage product that experienced temperature abuse (Sherlock et al., 1991).

Some retailers have already begun implementing TTIs on some of their refrigerated products. The Lifelines TTIs are presently being implemented on refrigerated products in the Monoprix food chain in France. As of November 1998, CUB stores in the Minneapolis/St. Paul, Minn., area are doing a market testing of the 3M tags on prepacked CAP/MAP hamburger. A large national dairy products manufacturer may also implement tags on specialty dairy products in the near future, and Eatsy’s of Dallas, Tex., began using Lifelines tags on their deli and refrigerated items in late 1998.

NINTH INNING

After evaluating the status of open dating, what must be done to increase its efficiency and guarantee a win for the home team (consumers and retailers)?

Although some of the open dating surveys in this study cited consumers’ confusion almost 20 years ago, current supermarket data do not suggest that state-regulated opendating laws have improved the consumers’ understanding of the dates over that time. One solution suggested by Ted Labuza at the University of Minnesota was to follow the guidelines as used by the meat industry. In other words, let the industry decide on what open date to use but require specific dating explanations when any date is used (Anonymous, 1979).

Since 1979, some states have added mandatory open dating legislation to suggest that there has been a growing consumer awareness of its potential benefits since the beginning of the century. However, the lack of uniformity among state laws is still apparent. It is only a matter of time before the inaccuracy or omission of an open date leads to a complicated lawsuit against a food industry or grocery chain. As the grocery industry strives toward more efficiency in its distribution and internal structure, the implementation of open dating would complement the goal of Efficient Consumer Response. At the same time, the technology of TTIs used in conjunction with an open date is increasing the chances of a wholesomeness guarantee for high-quality food products. USDA has recently recommended that this may be a useful approach, and the CUB food chain in the Midwest is now using the 3M tags (FSIS, 1998).

A federally mandated open dating system would not only educate consumers but assist in making the grocery retail industry more efficient. The trust that would develop among the retailers and their customers makes the home team the indisputable champions in the dating game.

THEODORE P. LABUZA AND LYNN M. SZYBIST

Author Labuza, a Fellow, and Past-President of IFT, is Morse Alumni Distinguished Teaching Professor, and author Szybist is Research Assistant, Dept. of Food Science & Nutrition, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN 55108. Send reprint requests to author Labuzza.

Edited by Neil H. Mermelstein

Senior Editor

References

ACNielsen Co. 1973. Study of consumer attitudes toward product quality. Northbrook, Ill.

Anonymous. 1971. Food stability and open dating. Food Science Dept., Rutgers Univ., New Brunswick, N.J.

Anonymous. 1979. Open dating and food waste. Minneapolis Tribune, October.

Anonymous. 1998. Retail temperature control lags food code. Food Reg. Weekly 1(2): 3-4.

Anonymous. 1999. Bad politics, bad meat. Los Angeles Times, Feb. 12.

Audits International.1990. 1989 National retail food product cold temperature evaluation. Highland Park, Ill.

Besfamille, M. 1998. Personal communication. Univ. of Toulouse, France.

Bishai, D.M., Bhatt, S., Miller, L.T., and Hayden, G. 1992. Vaccine storage practices in offices of pediatricians. Pediatrics 88:193-196.

Brody, A.L. 1997. Chilled foods distribution needs improvement. Food Technol. 51(10):120.

Brody, A.L. 1998. Minimally processed foods demand maximum research and education. Food Technol. 52(5): 66.

Butler, J. 1998. Sainsbury’s fined for selling stale food. PA News, June 23, p. 2.

Campden. 1992. A food industry specification for defining technical standards and procedures for evaluation of time temperature indicators. Tech. Manual 35. Campden Food and Drink Assn., Campden, U.K.

CDC. 1999. Update: Multistate outbreak of listeriosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov/od/oc/media/pressrel/r990114.htm).

Dowdell, S. 1996. Looking for a date. Supermarket News, June 17, pp. 27-36.

Duyvesteyn, W. 1997. Integration of the time-temperature history effect on the shelf life of fluid milk. M.S. thesis, Univ. of Minnesota, St. Paul.

Find SVP. 1988. Time-temperature monitoring products. A comparative intelligence report. Find/SVP, New York.

FDA. 1979. Summary of hearings on open dating. Food and Drug Admin., Fed. Reg. 44: 76007.

FNQUEB. 1999. Energy efficiency report. Far North Queensland Electricity Corp., Ltd. (www.fnqeb.com.au/index.html).

FSIS. 1995. Focus on food product dating. Food Safety and Inspection Service, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Washington, D.C. (www.fsis.usda.gov.80/oa/pubs/dating.htm).

FSIS. 1998. Guidance for beef grinders to better protect public health. Food Safety and Inspection Service, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Washington, D.C. (www.usda.gov/fsis/oa/haccp/guideb.pdf).

IFT. 1981. Open shelf-life dating of food. Inst. of Food Technologists, Food Technol. 35(2): 89-96.

Johnson, A.E., Donkin, A.J.M., Morgan, K., Lilley, J.M., Neale, R.J., Page, R.M., and Silburn, R. 1998. Food safety knowledge and practice among elderly people living at home. J. Epidemiol. Community Health, pp. 745-748.

Kalish, F. 1991. Extending the HACCP concept to product distribution. Food Technol. 45(6): 119.

Kantor, L.S., Lipton, K., Manchester, A., and Oliveira, V. 1997. Estimating and addressing America’s food losses. Food Rev. 20(Jan-Apr): 2-12.

Kurt Salmon Associates. 1993. Efficient Consumer Response (enhancing consumer value in the grocery industry). Presented at Food Marketing Institute, Washington D.C.

Labuza, T.P. 1982. “Shelf-Life Dating of Foods.” Food & Nutrition Press, Inc., Westport, Conn.

Labuza, T.P. and Schmidl, M.K. 1988. Use of sensory data in the shelf life testing of foods: Principles and graphical methods for evaluation. Cereal Foods World 33(2): 193-205.

Labuza, T.P. and Szybist, L.M. 1999. Current practices and regulations regarding open dating of food products. Working paper 99-01. Sloan Foundation, The Retail Food Industry Center, Univ. of Minnesota, St. Paul.

Malcata, F.X. 1990. The effect of internal temperature gradients on the reliability of surface mounted full history time-temperature indicators. J. Food Proc. Preserv. 14: 481-487.

Mistry, V.V. and Kosikowski, F.V. 1983. Use of time temperature indicators as quality control devices for market milk. J. Food Protect. 46(1): 52-57.

Moore, A.K. 1997. Dated thinking. Supermarket News, March 24, p. 40.

Narisetti, R. 1997. P&G’s new no-returns policy tells retailers to keep damaged goods. Wall St. J., March 24.

OTA. 1979. Open shelf-life dating of food. Office of Technology Assessment (OTA). U.S. Govt. Print. Office, Washington, D.C.

Seligsohn, M. 1979. Smashing the open-dating myth. Food Eng. 10: 20-25.

Sherlock, M. and Labuza, T.P. 1992. Consumer perceptions of consumer type time-temperature indicators for use on refrigerated dairy foods. Dairy, Food Environ. Sanitation 12: 559-565.

Sherlock, M., Fu, B., and Labuza, T.P. 1991. Systematic evaluation of time-temperature indicators for use as consumer tags. J. Food Protect. 54: 885-89.

Silverman, J. 1999. Interview with Tom Billy. Food Safety Report ISSN 1523-4533, Bureau of National Affairs, Washington, D.C., Feb. 17.

Springen, K. 1998. Safer food for a tastier millennium. Newsweek, Sept. 28, p.14.

Stickel, A.I. 1996. Values that make cents. Supermarket News, July 1, pp. 15, 18-19.

Taoukis, P. and Labuza, T.P. 1989a. Applicability of time temperature indicators as shelf life monitors of food products. J. Food Sci. 54: 783-788.

Taoukis, P. and Labuza, T.P. 1989b. Reliability of time temperature indicators as food quality monitors under non-isothermal conditions. J. Food Sci. 54: 789-793.

Taoukis, P., Fu, B., and Labuza, T.P. 1991. Time-temperature indicators. Food Technol. 45(10): 70-82.

Taoukis, P., Labuza T.P., and Saguy, I.S. 1997. Kinetics of food deterioration and shelf-life prediction. Chpt. 9 in “Handbook of Food Engineering Practice,” ed. K. Valentas, E. Rotstein, and R.P. Singh, pp. 363-405. CRC Press, Denver, Colo.

USDA. 1973. Food dating: Shoppers’ reactions and the impact on retail food stores. Marketing Research Report. Econ. Res. Service, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Washington, D.C.

USDA. 1995. Focus on: Food product dating. Consumer Education and Information Service, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Washington D.C. (www.fsis.usda.gov:80/oa/pubs/dating.htm).

Williams, M. 1998. Simple advice. Supermarket News, July 13, pp. 31-32.