The Matrix of Food Safety Regulations

What ends up on your plate is affected by many agencies, and today’s food technologist needs to be a combination of scientist, lawyer, and regulator to understand the complex matrix of food safety regulations under state and federal authority.

Gone are the days when a food technologist devised a totally new food product concept and had it on the shelves within months. Now there’s a maze of food regulations, food safety issues, and regulatory agencies with which to deal. Today’s food technologist needs to be a combination of scientist, lawyer, and regulator. Not understanding the complex matrix of food safety regulations under state and federal authority may put one’s company at grave risk.

This risk is even more intimidating because the lines of regulatory responsibility are sometimes blurred. While the primary responsibility for enforcing federal regulations for the safety of the food supply still rests with the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) and the U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services’ Food and Drug Administration (FDA), there are no less than 12 separate agencies that oversee aspects of food safety.

The legal authority of these 12 agencies derives from 35 separate federal statutes. These wide-ranging and sometimes overlapping food safety responsibilities represent a bewildering array of regulatory functions that are separated sometimes by the type of food product being regulated and sometimes by the type of contaminant.

This article presents some of the historic background in the development of the food regulations that exist today and provides the reader with an overview of the food safety regulatory matrix, as well as starting points for obtaining additional information regarding specific regulations.

A Brief History

It was far simpler when the food industry was young. Early in the 19th century, food quality regulation resided in the hands of state and local officials. These local regulators were often well acquainted with the food producers in their community. However, as increasing quantities of food moved across state lines, concerns about adulteration grew because the interstate movement of food was largely exempt from local regulation. It was partly out of these concerns that the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture was created in 1862. Part of USDA’s mission focused on the education and training of food producers.

As interstate trade continued to expand, the public became increasingly concerned about the wholesomeness of its food supply. Upton Sinclair’s book, The Jungle, although fictional, focused attention on the unsanitary practices in the meat packing industry and the plight of new immigrants working in that industry. In 1906, Congress passed the Food and Drugs Act (21 USC §§1 et seq.), often called the Pure Food and Drug Act, and the Federal Meat Inspection Act of 1907 (21 USC §§601 et seq.). [USC stands for United States Code, which contains the general and permanent laws of the U.S.] These acts prohibited adulterated or misbranded food in interstate commerce and required the inspection of meat processing facilities.

USDA was mandated to enforce this new legislation. Its Chemical Division, later named the Bureau of Chemistry, was responsible for conducting chemical analysis of food, food additives, and preservatives to evaluate their effect on public health. Later, the Bureau of Chemistry was renamed the Food and Drug Administration. USDA retained its authority related to meat, poultry, and eggs. But FDA and the food regulatory functions were transferred to the Federal Security Agency, which is now the U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services (DHHS).

In 1938, the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (21 USC §§301 et seq.) replaced the former Pure Food and Drug Act. The FD&C Act remains the primary statutory basis for food regulations today. The Poultry Products Inspection Act (21 USC §§451 et seq.) was passed in 1957 to augment the Federal Meat Inspection Act of 1907, and the Egg Products Inspection Act (21 USC §§1031 et seq.) was added to the legislation in 1970.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

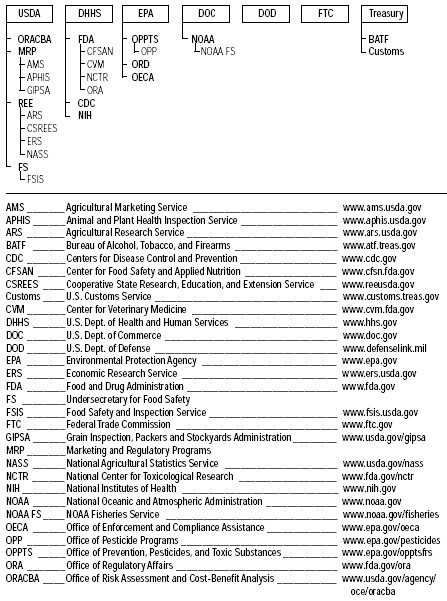

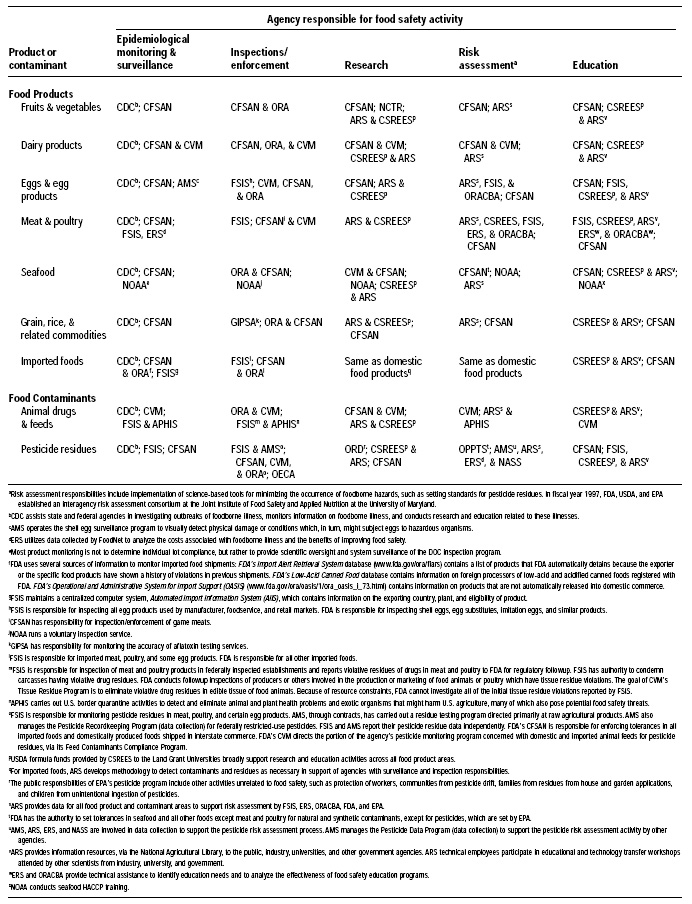

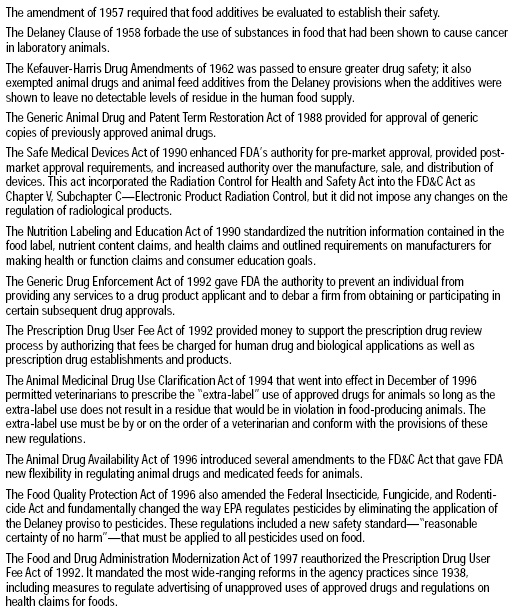

Fig. 1 and Table 1 on pp. 62 and 63 show the federal agency organizational framework and major components of the current federal food safety enforcement system; they are adapted from Ensuring Safe Food: From Production to Consumption (IOM/NRC, 1998)—this is an excellent reference that gives an overview of the catalog of food safety regulators, and the reader is encouraged to read it for additional details. Throughout the remainder of this article, references are given to specific statutes for additional information. Table 2 on p. 64 gives a summary of the major amendments to the FD&C Act of 1938 through 1997.

State Legislation and Regulation

At the state level, basic food laws contain provisions based on the FD&C Act of 1938 as amended, but because this federal legislation contains no comprehensive preemption provisions for the federal government, states retain a considerable amount of authority. In certain areas of labeling, however, there is express federal preemption requiring state provisions to be identical to the federal requirements. In most other areas,states are usually free to act unless the state legislation is inconsistent with federal law or the state’s involvement “stands as an obstacle” to accomplishing the objectives of a federal program. However, this is normally not an issue because FDA encourages states to play an active role in inspections and enforcement activities.

Similarly, states are encouraged to be involved in the federal meat, poultry, and egg related inspection programs of FSIS. If a state’s regulations are at least as strict as the federal programs’ (an “equal to” state), FSIS will cooperate with the state to allow it to administer its own safety programs for intrastate shipments.

FSIS also actively cooperates with state agencies in both inspection and enforcement activities. About half of the states in the U.S. have their own meat and poultry inspection programs in “equal to” states. Meat and poultry products that are only state inspected may only be sold within that state. Food safety is further extended by local government inspection of restaurants and foodservice establishments.

Compliance with all local, state, and federal food safety statutes and regulations is a legal and ethical obligation plus a wise business practice. Violations of applicable requirements can subject a company to civil or criminal enforcement actions initiated by local, state, or federal government authorities and can also subject a company to liability for damages brought by consumers or other companies in civil cases involving defective food products. These food safety violations may be considered negligence “per se” and may lead to imposition of strict liability for damage claims related to defective food products. In cases imposing strict liability, the plaintiffs only have to prove that the food product was defective, the defect existed when the food left the manufacturer’s control, and the defect caused injury to the plaintiff.

In addition, many contaminated-product insurance policies exclude coverage for any loss arising directly or indirectly out of the insured’s intentional violation of any government statute or regulation.

The following discussion reviews the regulatory authority of the five federal agencies that have the primary responsibilities for food safety as it relates to the inspection and enforcement of food composition, manufacturing, labeling, and advertising requirements. These five agencies were chosen because they have the main responsibilities for food safety, and they serve as a good example of the complexity of the regulatory matrix without making this article too complex.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Food Safety and Inspection Service

FSIS has broad statutory authority under three separate acts: the Federal Wholesome Meat Act that amended the Federal Meat Inspection Act in 1967 (21 USC §§601 et seq.); the Poultry Products Inspection Act of 1957 (21 USC §§451 et seq.); and the Egg Products Inspection Act of 1970 (21 USC §§1031 et seq.).

Under these Acts, FSIS carries out mandatory inspections of plants that slaughter livestock and poultry or plants that process shell eggs or liquid, dried, or frozen egg products. The agency follows the products throughout processing to assure wholesomeness and proper labeling. As mentioned above, under both the Federal Meat Inspection Act and the Poultry Products Inspection Act, if state inspection programs are at least as strict as the federal programs, FSIS will cooperate with the states to allow them to administer their own inspection programs for intrastate transactions. However, if the state is not operating a program at least equal to the federal requirements, the state may be “designated.” If that occurs, practically there is only federal inspection, and provisions of these Acts become applicable to sales within the state’s borders. Many states are now being designated because they no longer pay a share of the FSIS program costs. Additional information can be found at www.fsis.usda.gov.

Federal Meat Inspection Act

• Inspection Programs. Under the FMIA, cattle, sheep, swine, goats, horses, mules, and other equines are to be visually inspected by a federal inspector before slaughter (21 USC §603). The carcasses and organs are subject to a postmortem inspection (21 USC §604), including inspections during the preparation of meat products (21 USC §606). FSIS also imposes detailed facility, equipment, and sanitation requirements, and FSIS inspectors are responsible for checking compliance with these requirements.

Three exemptions from the FMIA inspection requirements exist: (1) custom slaughterers who prepare the carcass for the owner’s use; (2) retail meat markets and restaurants that sell directly to consumers where no meat processing occurs, as long as the storage and handling of the meat are covered by state or territorial law; and (3) a territorial exemption where inspection is impractical in unorganized territories (21 USC §623(a)-(b)). However, adulteration and misbranding requirements remain applicable.

This is a dynamic area where there is ongoing consideration of possible changes to make improvements in the safety of the food supply. The role of the hazard analysis and critical control points (HACCP) system, risk assessment, and the use of the FoodNet surveillance network are new improvements (Woteki, 1998). Some of the latest information can be found at www.usda.gov and www.fsis.usda.gov.

• Adulteration. FMIA lists circumstances under which meat articles will be considered adulterated and unfit for human consumption. The adulteration concept includes not only a meat or meat product that is filthy, putrid, or decomposed; but also the presence of poisonous or deleterious substances that cause the food to be injurious to health (21 USC §601(m)). In addition, if themeat or meat product contains pesticides, food additives, or color additives that are considered unsafe under the FD&C Act, the food is also considered adulterated.

The massive recall of Hudson Foods’ raw ground beef in 1997 occurred because of the presence of Escherichia coli O157:H7. The recall was based on an allegation of adulteration that was injurious to health, and this incident has prompted calls for increased regulation of microbiological contamination by USDA and FDA (Erickson, 1997).

FSIS stated in its final rule on meat and poultry irradiation (www.fsis.usda.gov/oa/background/irrad_final.htm) that the maximum absorbed dose of irradiation is 7 kGy for frozen meat and 3 kGy for poultry. It was determined that this dose could result in a significant reduction or elimination of certain microbial pathogens. Foods that are irradiated at levels above the legal doses are considered adulterated.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

• Misbranding/Labeling. The FMIA statute and USDA regulations in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) set out specific situations in which misbranding occurs, such as use of false or misleading labels, use of an incorrect product name, or lack of a label identifying one food as an “imitation” of another food (21 USC §601(n); 9 CFR §301.2). FSIS has also issued numerous standard of identity regulations that specify compositional requirements for products sold under commonly understood names (9 CFR §319). Labeling rules require that any new or proposed labels be submitted to FSIS for approval.The application for an approved label includes information on how the product is prepared and its content. In some cases, sample labels may have to be submitted for evaluation (9 CFR §317.4).

• Enforcement. FMIA contains provisions for both criminal penalties and civil sanctions. The most serious violations, including those committed with an “intent to defraud” or those involving felonies; lesser violations are misdemeanors. Civil sanctions under the Act include court orders to stop certain actions, seizure, and condemnation provisions (21 USC §674). In addition, FSIS has the authority to withdraw, deny, or suspend inspection services (21 USC §671). This authority is most often used when the recipient of inspection services has been convicted of a crime related to adulteration of food. distribution of adulterated articles, are felonies; lesser violations are misdemeanors. Civil sanctions under the Act include court orders to stop certain actions, seizure, and condemnation provisions (21 USC §674). In addition, FSIS has the authority to withdraw, deny, or suspend inspection services (21 USC §671). This authority is most often used when the recipient of inspection services has been convicted of a crime related to adulteration of food.

Poultry Products Inspection Act

• Inspection Programs. The PPIA requires that poultry and poultry products intended for human consumption be federally inspected. “Poultry” is defined to include chickens, turkeys, ducks, geese, and guineas (21 USC §453(e)), and “poultry product” is defined as the carcass or part or any product made from poultry (21 USC §453(f)).

The inspections may include examination of poultry before slaughter to determine if it “plainly shows” any disease or condition that should cause it to be condemned (9 CFR §§381.70-71). The Act leaves it to the agency to determine the extent to which such inspections are considered necessary.

Today, pathogenic bacteria are a predominant food safety concern. It is, of course, impossible for inspectors to see these bacteria on a carcass. Accordingly, there have been suggestions that the current effort and expense of inspecting individual bird carcasses might be better spent performing other activities. These suggestions could have a profound effect as modifications in legislation and regulations are considered in efforts to further reduce the incidence of foodborne microbial pathogens.

A recent statement by the Administrator of FSIS outlined how many and which types of defects pass through our current inspection system (www.fsis.usda.gov/oa/news/tb_083100.htm). Under FSIS’s Model Project plan being used to establish proposed inspection changes, plant inspectors would address these defects with additional FSIS checks and verification. The inspectors’ union challenged the Models Project in court, losing the initial hearing but winning on appeal.

Nonetheless, the present PPIA requires postmortem inspections on a bird-by-bird basis (21 USC §455(b)). Each carcass is examined using one of four approved systems of inspection, depending on the type of bird and type of operation. The specific examination will depend on the kind of product, type of preparation, procedures followed, and whether the product is in containers (9 CFR §381.145). Finished product inspection may also be required (9 CFR §381.309).

The exemptions from inspection requirements under the Act are similar to those under FMIA, including a personal use exemption, a “producer’s own poultry” exemption, a custom exemption, a retail store and restaurant exemption, and a territorial exemption. There is also a “small enterprise” exemption and one related to religious dietary laws. In addition to the specific inspection exemptions, there is a general exemption from all provisions of the Act for poultry producers who slaughter no more than 1,000 poultry each year that were raised on their own farm, who do not buy or sell poultry products other than those raised on their own farm, and who sell only intrastate (9 CFR §381.10(c)). However, these exemptions apply only to inspection. Sanitary standards are still applicable, as are the other provisions concerning adulteration and misbranding (21 USC §464).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

• Adulteration. The Act defines adulteration in the same manner as FMIA (21 USC §453(g).

• Misbranding/Labeling. There are 12 specific situations in which misbranding occurs with regard to any poultry product (21 USC §453(h)). These are identical to those itemized in FMIA. Prior approval of labels to be used with poultry and poultry products is also required, as under FMIA (21 USC §453(a)).

Egg Products Inspection Act

• Inspection Programs. The EPIA makes it illegal to buy, sell, or transport eggs or egg products for use as human food that are not inspected and labeled under the provisions of the Act (21 USC §1037(b)(2)). Egg handlers are prohibited from using eggs in the preparation of human food that do not meet the strict requirement of the Act (21 USC §1037(a)(2)). “Egg” is defined to include eggs of the domesticated chicken, turkey, duck, goose, or guinea (21 USC §1033(g)). “Egg product” means “any dried, frozen, or liquid eggs, with or without added ingredients” but does not include products that contain eggs in only a “relatively small proportion” or which have not historically been considered products of the egg food industry (21 USC §1033(f)).

The inspection programs, by requiring direct inspection and uniform consumer grade standards, focus on preventing eggs and egg products that are unfit for human consumption from reaching consumers. This regulatory approach focuses on “restricted eggs” (also referred to as “undergrade” eggs), which are defined as any “check, dirty egg, incubator reject, inedible, leaker, or loss.” (21 USC §1033(g)(8)). It is illegal to buy, sell, or transport restricted eggs, unless they are denatured, or to use them in the preparation of human food. In addition, the premises and facilities of egg and egg products are subject to minimum sanitary standards and inspections (7 CFR §§59.500 et seq.). USDA inspectors make periodic inspections of facilities of egg handlers who are engaged in transportation or shipping of eggs or who pack eggs for consumers. However, FDA retains authority with regard to the use of eggs in institutions such as bakeries and restaurants where the eggs are processed and used as an ingredient in another food.

A limited exemption exists (21 USC §1044; 7 CFR §59.100) for poultry producers who sell eggs from their own flocks directly to household consumers. Each sale is limited to 30 dozen eggs, and if it occurs door-to-door or at a site away from the site of production, the restrictions on loss and leaker eggs still apply.

There have been a series of recent federal rulemaking changes that affect the marketing of shell eggs. These are summarized in a Shell Egg Regulations Overview (www.ams.usda.gov/poultry/regulations/eggpdfs/ShellEggOverview.htm). Other proposed changes may affect the shell egg food safety surveillance program under the Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS). These changes include the proposal to ban repackaging of eggs for retail sale and the packaging of officially identified eggs older than 15 days, the requirement that eggs with an official consumer grade be transported and stored at 45°F or colder, and the requirement that eggs be labeled to indicate that refrigeration is required. These regulations were moved from part 59 to part 57 of the CFR.

• Adulteration. EPIA specifically defines “adulterated” eggs and egg products very broadly (21 USC §1033(a)) and tracks closely the definition of “adulterated” used in FMIA and PPIA. If eggs are adulterated, they cannot be used for human food and must be disposed of by denaturing (21 USC §1039; 7 CFR §59.504(c)).

• Misbranding/Labeling. EPIA establishes uniform labeling and packaging requirements and prohibits the use of false or misleading labeling or containers (21 USC §§1036, 1052). Prior approval of any identification devices, marks, or certificates is required (21 USC §1037(e)).

• Federal/State Cooperation. One of the primary reasons for enactment of EPIA was to eliminate an inconsistent and confusing variety of state requirements related to eggs by imposing uniform standards. In most cases, the Act preempts state requirements, but inspection is generally carried out by the states under USDA supervision and at USDA expense (21 USC §1038).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Voluntary Inspection Programs

FSIS operates a number of voluntary inspection programs covering food articles not otherwise governed by the three mandatory programs described above. For example, any article of human food derived from meat, meat by-products, or meat food products, as well as animal casings, may be voluntarily inspected and identified as “federally inspected and passed” (9 CFR §350). Similarly, food products from poultry carcasses, not otherwise covered by the Act, may be voluntarily inspected (9 CFR §362).

A processor of exotic animals, e.g., reindeer, elk, deer, antelope, bison, and water buffalo, may apply for approval as an official exotic animal establishment and, if approved, receive (fee-based) inspection services. In addition, certification of the exotic animal meat and meat food products as “inspected and passed” follows ante-mortem and post-mortem inspections that track the requirements under FMIA (9 CFR §§352.7, 352.10-352.11). A voluntary inspection program for rabbits slaughtered for human food operates in a similar manner (9 CFR §354).

Food and Drug Administration

FDA has a broad mandate under the FD&C Act regarding food safety and wholesomeness. “Food” is broadly defined to include articles used for food or drink for man or animal, chewing gum, and any food components (21 USC §321(f)). This mandate covers the inspection of food plants and the establishment of standards for composition, quality, and safety of food and food additives, as well as economic standards to assure consumer confidence in labeling. FDA requirements for small businesses are summarized at www.fda.gov/opacom/morechoices/smallbusiness/blubook/blubook2.htm.

• Inspection Programs. FDA’s inspection programs are directed toward any article used for food or drink except for meat, poultry, and egg products that are regulated by USDA. FDA inspects food plants and animal feed manufacturing facilities. These inspections of both the regulated establishment (plant) and processed products (21 USC §374) are not continuous inspections, but rather occur on a limited basis. The inspections may range from abbreviated to comprehensive inspections depending on whether they are in response to some reported product problem such as contamination.

Inspections are generally unannounced, and written statements are required regarding certain violations detected during the inspection. The inspector must also provide a written receipt of any samples taken, and FDA must provide written notice of certain laboratory analyses of samples (21 USC §374).

• Adulteration. Adulteration is defined in a manner consistent with FMIA and PPIA. A food article is adulterated if it contains any poisonous or deleterious added substance which may render it injurious to health, if it contains any unsafe substances such as dangerous levels of pesticide residues, if it consists of any filthy, putrid, or decomposed substance, or if it is otherwise ”unfit for food” (21 USC §§342(a)-(c)). A food is also considered adulterated if it comes from a diseased animal or one that died other than by slaughter, if it has become injurious to health because of a contaminated food container, or if there has been an omission or subtraction of any “valuable constituent” from the food. An action that causes adulteration is a violation, as is any action that causes the introduction or delivery of adulterated food into interstate commerce or the receipt, delivery, or offering for delivery of adulterated food in interstate commerce (21 USC §331).

For naturally occurring “poisonous or deleterious” substances, adulteration occurs only if the substance will “ordinarily” render the food injurious to health. For added “poisonous or deleterious” substances, the test is whether the substance “may” render the food injurious to health. The added substances can be regulated, among other ways, by the congressionally mandated food additives system (21 USC §348) or by a tolerance system (21 USC §§346, 346a).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

The statute’s definition of food additive includes a substance which is intended to become a component of food or otherwise affect the characteristics of food. The statute does not apply to a substance which is considered “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) as determined by experts qualified by scientific training and experience to evaluate the safety of such substances (21 USC §321(s)). If a substance meets the definition of a food additive, it must receive FDA approval before it can be used. However, the use of a substance that was approved by USDA or FDA before 1958 is exempt from food additive status. Generally, use of a food additive without approval causes a food to be adulterated (21USC §§342 (a)(2)(A)(B), 346(a)).

Separate regulations exist for chemical pesticide residues in or on a raw agricultural commodity or in a processed food. Tolerance levels for chemical pesticide residues are set by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and enforced by FDA (21 USC §346(a)). While FDA enforcement of policies on chemical residues in foods, such as dioxin, are strict, these policies are much more consistent than those seen in a recent incident in central European countries (Crawford, 1999).

• Misbranding/Labeling. The FD&C Act provides that a food shall be deemed to be misbranded if the labeling is false or misleading; if the food is offered for sale under the name of another food; if the food is an imitation of another food and not so labeled; or if the container is filled, made, or formed so as to be misleading (21 USC §§343(a)-(d)).

The label must identify the manufacturer, packer, or distributor and state the quantity of the contents. The required labeling must be prominently and conspicuously displayed. If the label represents the food to be one for which a definition and standard of identity has been prescribed by regulation, the food must conform to that definition and standard. Likewise, if a standard of quality or of fill has been prescribed, the food must meet the standard or bear a label statement that indicates that it does not meet the standard (21USC §343(e-m). The label must also bear a “statement of the identity” of the food and list the ingredients contained in the food (21 CFR §§101.3-101.4). Artificial flavoring, artificial coloring or added natural colors, and chemical preservatives must be revealed (21 USC §343(k)).

• Enforcement. If FDA learns from an inspection or from another source of information that a food has been adulterated or misbranded, the agency can recommend that a U.S. attorney initiate in court a civil seizure action in order to seize and condemn the food. The agency can also recommend that an injunction action or criminal prosecution be initiated in court against the company or individual person responsible for the violation (21 USC §§332-334).

Labeling violations that are based on the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act (15 USC §§1451 et seq. (1966) are not subject to criminal sanctions. FDA may request a recall of food products that are in violation if they present a rationale for an “urgent” situation.

The FD&C Act provides for the first violation, usually a misdemeanor, with possible imprisonment of not more than one year or a fine of not more than $1,000, or both. To bring the action as a felony, FDA must show either a prior misdemeanor conviction or a knowing violation with intent to defraud or mislead (21 USC §§337(a)(1)-(2)). An example of this enforcement provision is the penalty leveled against the officers of the manufacturer of BeechNut apple juice, where adulteration with water was proven (Wrolstad, 1991).

• FDA-State Cooperation. The FD&C Act does not generally prevent state involvement in food safety matters. FDA has encouraged cooperative relationships with state agencies and in some cases has left the major enforcement activities primarily in the hands of the states. For example, regulation of milk and shellfish and the oversight of retail food stores and restaurants are generally accomplished by the states with technical assistance from FDA. Procedures for the FDA–State Cooperative programs are based on the Grade A Pasteurized Milk Ordinance, 1999 Revision, and are at http://vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~acrobat/pmo99-1.pdf. Procedures covering cooperatives’ interstate milk shipments are at http://vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~ear/proceed.html.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

• FDA Guidance Concerning Produce. FDA has published guides for industry to help minimize the microbiological hazards from fresh fruits and vegetables (http://vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/prodguid.html) and sprouted seeds (http://vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/sprougd1.html). These detailed guides address personal hygiene, facilities sanitation, and control of potential hazards from water and manure.

In a recent example of the complexity of the food safety matrix, USDA held a conference and published a proceedings (USDA, 1999) that addressed current educational needs to help ensure that both domestic and imported fruits and vegetables meet FDA’s guide for highest standards for food safety. USDA’s AMS has published a final rule (7 CFR §47) under the Perishable Agricultural Commodities Act of 1930 (7 USC §§499 et seq.) that establishes fair trading practices for fresh and frozen fruits and vegetables (www.ams.usda.gov/fv/paca/rules-txt.htm).

FDA contracts with states to carry out many inspection responsibilities for food sanitation and medicated animal feeds. It also uses a commissioning system to obtain the assistance of state officials to conduct inspections and examinations. This statute imposes no limitations on a state’s enforcement of adulteration actions to either restrain violations or seek civil enforcement of violations, but it does limit some misbranding actions by the states (21 USC §337(b)(1)).

• FDA’s Changing Role. In recognition of trade with other countries, as well as an attempt to solidify the safety of the national food supply, FDA has implemented the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997 (FDAMA, 21 USC §§301 et seq.). One of its main goals is to improve the flow of information to consumers and food processors. The U.S. is currently engaged in trade discussions over genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in foods, the European Union’s ban of hormones in meat, and increased labeling requirements for both domestic and imported food items. The U.S. maintains that the current labeling requirements are sufficient to inform both consumers and trading partners of the contents of food products. Labeling requirements may change as a result of these ongoing trade discussions, FDAMA, or the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (NLEA) of 1990 (21 USC §343 et seq.), discussed below.

Other new initiatives may form the food safety regulations of the future. President Clinton’s Food Safety Initiative of 1997 (http://vm.cfsan.gov/~dms/fsreport.html) was directed to better coordinate actions among government agencies in this area. Revisions in 1997 and 1999 to the FDA Food Code provide a scientifically based foundation for food safety advice to federal, state, and local agencies, including additional requirements for potential risks associated with eggs and sprouts; new methods to advise consumers of increased risks of foodborne illness; clarification of “barehand contact” prohibitions for ready-to-eat foods; modifications of time and temperature controls for meat, pork, and beef served rare; safe-handling instructions for poultry packers and retailers of meat; and changes to recommendations for oxygen packing. The 1999 Revision of the Food Code, modified April 15, 1999, can be downloaded from http://vm.cfsan.gov/~dms/fc99-toc.html.

The proposed Consumer Food Safety Act and the proposed National Uniform Food Safety Act would establish a National Food Safety Program, require registration of food processing and importing facilities, provide for unannounced inspections, provide civil monetary penalties for violations, and require additional labeling for certain foods. The Consumer Food Safety Act (H.R. 2129) was introduced in June 1999, sent to the House Committee on Commerce, and referred to the House subcommittee on Health & Environment within Commerce. The National Uniform Food Safety Act (S. 2810) was introduced in June 2000 and referred to the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation.

Environmental Protection Agency

EPA is given specific authority under the FD&C Act to establish pesticide chemical residue tolerances in both raw agricultural commodities and processed food (21 USC §346a(b)). EPA’s Office of Pesticide Programs determines the safety of new pesticides and sets tolerance levels for all pesticide residues in foods. If the quantity of the residue exceeds the tolerance, the food is considered unsafe and meets the definition of “adulterated” (21 USC §342a(2)(B)). Tolerances, defined as the maximum allowable pesticide residue levels, are set for specific pesticides and specific commodities. This tolerance limit is set at a “safe” level, i.e., a level where “there is a reasonable certainty that no harm will result from aggregate exposure to the pesticide chemical residue.” (21 USC §346a(b) (2)(A)(ii)). The tolerance level is not to be established unless there is a practical method for detecting and measuring the levels of pesticide chemical residue in or on the food (21 USC §346a(b)(3)(A)). In some cases, EPA may approve an exemption from the requirements of a tolerance if it is determined that the exception is safe (21 USC §346a(c)(2)(A)(i)).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

FDA enforces EPA’s pesticide residue tolerance levels and publishes directions for safe use of pesticides in the production of food. FDA also uses EPA’s water quality standards for bottled water sold in interstate commerce (http://vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~lrd/fr98511a.html).

If a person introduces or delivers into interstate commerce a food that is adulterated because of the unauthorized presence of a chemical pesticide, a civil penalty may be imposed instead of the remedies of injunction, seizure, or criminal prosecution. However, farmers who grew the article of food that is adulterated under these provisions are specifically exempt from civil penalties (21 USC §333(f)(2)(A)(B)). More information is available at www.epa.gov.

Federal Trade Commission

FTC, FDA, and USDA share jurisdiction over claims made by food manufacturers. In 1954, a memorandum of understanding outlined their cooperation to help eliminate duplication of efforts and promote consistency (FDA/FTC, 1971). They agreed that the regulation of food advertising would be primarily in the hands of FTC, while FDA would have the primary responsibility for regulating food labeling.

FTC’s statutory authority with regard to food advertising is broad. In general, FTC requires that any objective claim made in advertising must be supported by a “reasonable basis of substantiation” that the advertiser has in its possession at the time the claim is first made. It is unlawful to disseminate a false advertisement for the purpose of inducing, or for the purpose that is likely to induce, the purchase of food (15 USC §52(a)). It is also considered an unfair or deceptive act or practice to disseminate or cause the dissemination of any false advertisement for food (15 USC §52(b), referring to 15 USC §45).

The passage of the NLEA did not change FTC’s statutory responsibilities to prohibit deceptive advertising practices. However, in this new and expanding area, FTC recognizes FDA’s scientific expertise and seeks harmonization of nutrient content and health claims that may differ in the total context of an advertising campaign from those simply appearing on the food’s label. In advertisements, FTC uses the FDA serving size as a reference and requires the use of FDA-defined terms in a manner consistent with FDA regulations. Foods that make health claims must contribute significantly to a healthful diet. FSIS and FDA regulations implementing NLEA goals were designed to prevent deceptive and misleading claims, standardize and limit terms permitted on labels, and, importantly, use nutrient content and health claims as education tools for consumers.

Food processors, advertisers, and educators should avail themselves of FTC’s guidance in making nutrient content and/or health claims in food advertising. This reference (www.ftc.gov/bcp/policystmt/ad-food.htm) goes into detail, with copious footnotes, on what constitutes deceptive advertising and when omission of information may be considered deceptive. It states in part that “Advertisers, therefore, should comply with all relevant provisions of the Enforcement Policy Statement on Food Advertising and not simply the provision that seems most directly applicable.” Additional information is available at www.ftc.gov.

NOAA Fisheries Service

The U.S. Dept. of Commerce’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries Service, formerly the National Marine Fisheries Service, oversees the management of fisheries in the U.S. and is responsible for seafood quality and grading. Under the 1946 Agricultural Marketing Act (7 USC §§1621 et seq.), NOAA Fisheries operates a voluntary inspection program for fish in conjunction with FDA. FDA regulates processing of both shellfish and “finfish” that are used for food, just as it can regulate any other food. In 1995, FDA issued its final rule on HACCP plans that must be in place for seafood processors (21 CFR §123) and a guidance document that consists of recommendations to aid seafood processors in developing their own HACCP plans (http://vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/haccp-2.html).

NOAA Fisheries has its own authority for the promulgation of grade standards, inspection, and certification of fish and shellfish. Its inspection services are offered on a fee basis and are performed by sampling to determine whether fish meet appropriate grade standards. If the sample complies with the product description, the applicable standard of quality, and the desired grade, then a grade, such as U.S. Grade A, is assigned to the lot from which the sample is taken, and an inspection certificate is issued by the inspector (50 CFR §§260.21, 260.26).

Approved grade marks and other inspection identifications may be used on the container, labels, or in advertising for the final processed product. The grade marks indicate the assigned U.S. Grade Standard, and the inspection marks indicate that the product has been “Packed Under Federal Inspection.” (50 CFR §260.86).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Continuous inspection on a contract basis may also be requested for an “official establishment” which processes and packs fishery products (50 CFR §260.96). An official establishment (or plant) is one or more buildings of a single plant, where the facilities and methods of operations have been approved by the Administrator as being suitable and adequate for the grading service, where grading is carried on in accordance with the regulations (7 CFR §70.1).

The contracting party must handle and store all raw materials under sanitary conditions, as well as maintain the establishment itself in a sanitary condition (50 CFR §260.97(c)(1)). Labels that refer to federal inspection or U.S. Grade Standards must be used properly and only on products that are processed and packed under the fishery products inspection services program (50 CFR §§260.97(c)(3)-(6)). Codes must be used on containers to enable positive identification of the products, and reports of processing, packaging, grading, laboratory analysis, and output of products are required (50 CFR §§260.97(2), (7)).

The premises in which seafood is processed must be maintained free from conditions that might result in contamination of food, such as strong, offensive odors, or conditions that might attract rodents, insects, or other pests (50 CFR §260.98). Detailed sanitary rules apply to maintenance of the buildings, structures, facilities, and equipment; and the operation and operating procedures must be in accordance with an effective sanitation program (50 CFR §§260.99-260.103). More detailed information is available at www.nmfs.noaa.gov.

Agricultural Imports

Foods imported into the U.S. are generally required to meet the same rules and regulations as domestically produced foods. In addition, imported foods must have the appropriate filing documents completed by the importer or its agent, and be authorized by the U.S. Customs Service and the U.S. Treasury Dept.

The import filing documents may be presented before the food arrives at the port of entry. There are specific requirements, and a license or permit is required from the agency responsible for importing animal products, fruits, nuts, meat and meat products, milk, dairy and cheese products, plants and plant products, poultry and poultry products, trademarked articles, and vegetables.

A more complete introduction to the laws and regulations for imports can be found in USDA’S Food and Agricultural Import Regulations and Standards Report (www.fas.usda.gov/itp/ofsts/us.html).

USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) also requires a phytosanitary certificate for many commodities to ensure that they will not introduce any pests or disease into the country. Additional information on these requirements is available at www.aphis.usda.gov/ppq/ss/permits/pests/.

Finding What You Need

Although the matrix of differing agencies having similar responsibilities for the same food product may be bewildering, it is vital for food scientists to be familiar with the requirements of local, state, and federal agencies, especially in the area of food safety, to be successful. We hope that this article will help you find in-depth regulatory information you need to successfully develop and market your food product.

by Jake W. Looney, Philip G. Crandall, and Anita K. Poole

Author Looney is former Dean of the Law School and Distinguished Professor of Law at the National Center for Agricultural Law Research and Information (NCALRI), University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701; author Crandall, a Professional Member of IFT, is Professor, Dept. of Food Science, 2650 Young Ave., University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72704; and author Poole, a former Research Fellow at NCALRI, is with the Public Defender’s Office, Washington County, Fayetteville, AR 72701. Send reprint requests to author Crandall.

This article is based on “Food Safety: State and Federal Standards and Regulations,” a multi-volume compilation of educational and informational documents completed in 2000 by the National Center for Agricultural Law Research and Information as a research project in conjunction with the National Association of state Departments of Agriculture. The complete work (a federal section and 50 state sections of laws) is available at www.nasda.org and http://law.uark.edu/arklaw/aglaw.

The authors thank Corliss O’Bryan, Teresa Cole, and the staff of the National Center for Agricultural Law Research and Information for their assistance in the preparation of this article. This article is meant to inform and is not intended to provide legal advice. The Internet sites cited were visited on January 30, 2001.

Edited by Neil H. Mermelstein,

Senior Editor

References

Anonymous. 1999. Guide to regulatory agencies. Food Proc., Sept., pp. 7-9.

Crawford, L. 1999. Implications of the Belgian dioxin crisis. Food Technol. 53(8): 130.

Erickson, O.P. 1997. Beef recall prompts push for new legislation. Food Prod. Design. 7(7): 23, 25, 27.

FDA/FTC. 1971. Memorandum of Understanding. Working agreement between FTC and Food and Drug Administration, 4 Trade Reg. Rep (Commerce Clearing House ¶ 9,850.01).

IOM/NRC. 1998. “Ensuring Safe Food: From Production to Consumption.” Comm. to Ensure Safe Food from Production to Consumption, Inst. of Medicine, Natl. Res. Council. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C (www.nap.edu).

Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990, Pub. L. No.101-535, 104 stat.2353 (codified in part at 21 USC §343(i), (q) and (r)).

USDA. 1999. Proceedings of the National Science and Education Conference: Toward implementing the “Guide to Minimize Microbial Food Safety Hazards for Fresh Fruits and Vegetables,” Orlando, Fla., April 6-7. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture,Washington, D.C.

Wrolstad, R.E. 1991. Ethical issues concerning food adulteration. Food Technol. 45(5): 108,112,114, 117.

Woteki, C. 1998. The “State of the Union” on food safety. USDA keynote address. J. Assn. Food and Drug Officials 62(2): 9-15.