2001: A Spice Odyssey

There’s nothing science fiction about these new spice developments.

I don’t think the spirit of late film-maker Stanley Kubrick would mind if I took some liberties with his classic sci-fi title. Besides, the revised title really does capture this month’s ingredients topic: spices and the broad—some would say limitless—possibilities that they offer today. (See also the Ingredients section on page 68 for a roundup of spices shown at the recent Chicago Section Suppliers’ Night.)

Spice consumption in the United States has reportedly doubled since 1980, growing to nearly four pounds per person. And, according to recent statistics from the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture and the American Spice Trade Assn. (ASTA), America’s total spice consumption is close to reaching 1.4 billion pounds per year by the end of 2003.

This article will provide an update on several of these popular spices and, in particular, address new developments in functionality, health benefits, sourcing, consumer preferences, the creation of novel spice combinations, preparation, and applications.

However, before we begin our voyage of discovery, there are some points about spices that may need further reviewing or clarifying.

According to ASTA, a spice is “any dried plant product used primarily for seasoning purposes.” A working definition such as this one is broad enough to include herbs, spice seeds, roots, spice blends, and other plantbased elements. However, this article will not cover dehydrated vegetables, vanilla, and some botanical herbs because the Food and Drug Administration’s definition of spices does not include dehydrated vegetables (USDA requires that onion and garlic be listed as “flavors); vanilla, derived from beans, is primarily used as a flavoring extract; and certain botanical herbs over recent years have been promoted primarily as nutraceuticals rather than as seasonings or flavorings. Spices that contribute color, such as paprika, turmeric, and saffron require separate labeling and will not be discussed here.

A particular spice can come from different regions. Consequently, the flavor, aroma, consistency, and overall quality of the spice can vary dramatically depending on the location, which influences such factors as climate, soil, seed, harvesting, and storage. Not surprisingly, cost versus quality must be taken into consideration as well as the political stability of the region and restrictions on trade. One could easily write an entire book on the variations between spices from different regions and the factors that affect their quality or trade. For the present, this article will discuss each spice in a more generic manner, although it will allude to some of the differences already mentioned.

Spices have a long and rich folklore surrounding their cultural and medical benefits. (For an entertaining and informative read, I can highly recommend The Book of Spices by Frederic Rosengarten, Jr., published in 1973, or a visit to Web sites such as www.astaspice.org or www.mccormick.com.) Interestingly, today’s research is confirming some of the health benefits of spices that were learned during antiquity. This article will discuss some of the recent research. However, usage levels always need to be considered. A pinch of spice for flavoring will likely not be enough to make a food safe from microbes or prevent a disease. But spices in combination with other ingredients and processes may play a greater role in the area of health maintenance.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Spices are also playing an important role in the different ways foods are prepared. For example, spice rubs have gained new popularity with chefs. Rubbing in dry mixtures of spices before cooking meats, fish, and poultry can create deeper flavor than marinades, sauces, or basting liquids. Also, rubs can be used with a variety of different cooking methods, such as grilling, roasting, sauteing, and braising. The number of spices used in the mixture can vary, depending often upon the experience of the chef. Toasting dried seeds such as sesame, cumin, and fennel can release maximum aroma and flavor from the seeds. Meat, fish, and other dishes may be served in “crusts” of whole seeds for textural and visual appeal. Seasoned dishes may be surrounded by a sauce created in the form of a light, creamy foam. A variety of foods (not to be confused with appetizers) may also be prepared in smaller portions for sampling, and this approach can take advantage of the wide range of flavors and aromas that spices offer. Spices can be sprinkled onto dishes after they are cooked. One chef sprinkles the spices that are used in the dish around the rim of the plate for decoration. These are only a few of the innovative ways that foods are being prepared today. Some of these methods will be referred to throughout the article.

Finally, spices may be classified in several ways: for example, (1) by parts of the plant from which the commercial product comes; (2) by their properties; (3) according to family; and (4) as they might appear on an organized spice shelf, alphabetically. One can learn a great deal about spices, depending on how you organize them. One can also get easily confused, as there are some strange relatives in every family. Because of space and time constraints, and because I don’t want to get too confusing, this article will organize the spices individually, updating their benefits and possible reasons for popularity.

With some potential confusions hopefully resolved, let’s now look at some of these popular spices.

Cinnamon

Over the holidays, most of us have probably sampled such products as pumpkin pie, hot cider beverages, spiced vegetable salads, raisin toast, and compote. If you did, then you’re familiar with the sweet-spicy aroma of cinnamon—a spice which is popular not only during festive occasions, but throughout the year.

Cinnamon is derived from the dried bark of trees in the evergreen family of the genus Cinnamomum. Actually, there are several varieties of trees that produce cinnamon with varying characteristics. For example, most of the cinnamon (actually cassia) in the U.S. comes from Indonesia, as opposed to Sri Lanka (Ceylon) versions which have milder flavor and aromas. While the U.S. prefers the Indonesian variety, countries such as Mexico and Latin America favor the type that originated in Sri Lanka—this bark is much thinner, much lighter in color, and, again, much milder in flavor (from lower oil content).

In the past, political events have had much impact on spice trade. In the cinnamon market there have been several important changes. For instance, cinnamon is now coming from South Vietnam where trade has previously been interrupted since the fall of the country’s government on April 30, 1975. However, it should be noted that Saigon cinnamon, as it once was called, is now listed as Vietnamese Cassia; beyond this name change, the grade has the same premium qualities—intensely sweet taste and exceptionally high volatile oil content. The Vietnamese product is reportedly increasing in demand since its return to the U.S. market in 1996. Also, China has become an increasingly important source of cinnamon since U.S. has resumed trade with the country. China sends two types, Tunghing and Sikiang. Grown near the Vietnamese border, both have flavor similar to the Vietnamese product (though lower in oil).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Cinnamon’s component cinnamic aldehyde is chiefly responsible for imparting its characteristic odor and flavor, described as woody, musty, and earthy. It is warming to taste, and the finer the grind, the more quickly it is perceived by the taste buds.

The sweet and hot tones of cinnamon make it especially suitable in foods that emphasize heat or a spicy heat balanced by sweetness. Once primarily a baking spice, cinnamon may now be used to accent the flavors of meats, poultry, vegetables, and other foods. For example, a new snack item using cinnamon recently made its debut into the marketplace. Planters Sweet Roasts® consists of almonds, peanuts, and pecans accented with cinnamon. (Also new in this line was almonds, cashews, and peanuts flavored with vanilla.)

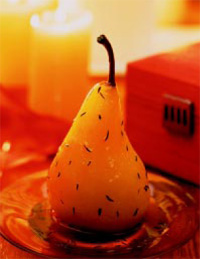

Recipes developed by McCormick & Co., Inc. include Cinnamon-Thyme Poached Pears (ripened pears are simmered in a mixture of maple syrup, cinnamon sticks, and thyme to bring new flavor to the fruit) and Southwestern Cinnamon Steak Rub (cinnamon combines with cumin seed, paprika, and oregano with a touch of brown sugar to infuse flavor into the steak).

According to McCormick & Co., cinnamon is a key ingredient in North African cuisine which is growing increasingly popular. Some dishes include Orange and Radish Salad with Cinnamon Vinaigrette, Moroccan Spice Braised Chicken with Dates and Almonds (cinnamon combined with cumin and ginger), Cinnamon Beef Tagine (cinnamon with bay leaf, cumin, ginger, and red pepper), and Egyptian Koshary Pasta (a meatless dish containing layers of rice, lentils, and pasta with a tomato-cinnamon sauce).

Although the spice has been used medicinally for thousands of years, recent scientific research is confirming its potential value in such areas as disease prevention and antimicrobial properties.

Test tube studies conducted by the USDA Agricultural Research Service found that certain substances in cinnamon make body cells more responsive to the hormone insulin, which regulates glucose metabolism—the process in which cells convert glucose to energy and keep blood sugar levels normal. If future research shows that these substances do the same thing in people, then the spice may have the potential to delay or prevent adult-onset (type 2) diabetes.

The researchers found that cinnamon’s most active compound, methyl-hydroxy chalcone polymer (MHCP), increased glucose metabolism approximately 20-fold in a test tube assay of fat cells. None of the other plant extracts evaluated came close to MHCP’s level of affecting glucose metabolism. Furthermore, MHCP provided an important side effect—preventing the formation of damaging oxygen radicals in a blood platelet assay. Other studies have shown that antioxidant supplements can reduce or slow the progression of various complications of diabetes.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

ARS scientists are currently seeking a patent application on the compound. MHCP is the first chalcone—a type of polyphenol or flavonoid—reported in cinnamon. MHCP and other active compounds are water soluble and are not found in the spice oils sold as food additives.

An article on the test tube studies appeared in the July 2000 issue of Agriculture Research magazine.

Studies have also looked at the antimicrobial properties of spices such as cinnamon. In 1999, researchers at Kansas State University studied the antagonistic effect different doses of cinnamon alone and in combination with preservatives would have on E. coli O157:H7 in apple juice. One million E. coli bacteria cells were added to one mL of pasteurized apple juice. (The number of bacteria cells added to the juice was higher than the number of bacteria cells that would be found in consumer food products and was done for experimental purposes only.) After adding approximately 0.3% of cinnamon—more than one teaspoon of the spice to a 64-oz bottle—about 99% of the E. coli was eliminated.

Previously, the researchers found that variety eral spices, including garlic, clove, cinnamon, oregano, and sage killed 99% of E. coli bacteria in ground beef.

Although amounts of spices and herbs added to foods are generally too low to prevent spoilage, studies suggest that microorganisms can be controlled through a combination of factors—including the effective use of spices as antimicrobials.

Cumin

A key component in both chili powder and curry powder, cumin is the dried seed of the herb Cuminum cyminum, a member of the parsley family. Its sensory profile is characterized by a strong musty/earthy flavor which also contains some green/grassy notes. Cumin aldehyde is the principal contributor to the spice’s flavor and aroma.

According to ASTA, the spice has shown a substantial growth in recent years, primarily as a result of the increased popularity of chili and Mexican foods. The total demand in the U.S. is estimated to have increased 50% or more in the past decade.

Although most of the cumin seed used in the U.S. goes into chili powder, followed by manufactured chili con carne, chili meat products, and other Mexican-style foods, cumin is also an excellent spice for rice dishes, curries, stuffings, sauces, and marinades. Mc-Cormick & Co. notes that the earthy, pungent flavor of cumin brings depth to stews and soups. Cumin may also be used in breads and some sweet baked goods. Although its usage in cheese is similar to caraway, the result is distinctively different.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Cumin is also an important spice in a sevvariety of other ethnic cuisines. It may be used in combination with cinnamon in a variety of dishes from Northern Africa. As the influence of Indian cuisine, Middle Eastern, and Northern African dishes grow stronger, there is obviously much potential for cumin. Also, after chili peppers, cumin is perhaps the most distinguishing flavor characteristic of Latin American foods in general.

Cumin seeds may be toasted, as well, to release their intense aroma and flavor, and then added to a novel dressing. Available from McCormick, the recipe, Grilled Corn, Papaya, and Black Bean Salad with Toasted Cumin Dressing, has an appealing range of colors, textures, and flavors.

Another novel preparation method is used to create Orange-Cumin Roasted Chicken, a recipe also available from McCormick. The recipe uses the earthy flavor of cumin to complement a citrus flavor, in a spice paste that coats the chicken. The paste should resemble a thick tomato sauce. Once the chicken is evenly coated, high-heat oven roasting is used to intensify the flavor. This technique relies on high heat (425–450°F) to “fast cook” the dish with dry heat, creating a tender, juicy inside and crispy outside. Cumin seeds are naturally toasted while the dish is roasting. Layered flavors and textures from the use of ground cumin and toasted cumin seeds and the orange juice and peel provide a flavor with more dimension.

Cumin is native to Egypt and the shores of the Mediterranean. Today, the principal supplier of the spice is Iran. India is actually the world’s largest producer of the spice, but it is also the largest consumer, which, of course, has a large impact on its exporting. Nevertheless, it is still a major source, producing a cumin which is very similar to the Iranian variety. Other sources include Syria, Pakistan, Egypt, and Turkey.

Because the plant adapts to both warm and cool climates, it is widely cultivated in countries around the world. Consequently, there is potential for new sources, particularly if new political and economic problems develop. According to ASTA, countries which have not had much to export in the past could well boost production and become tomorrow’s leading sources.

Researchers in India are studying cumin’s anti-cancer potential and some herbalists recommend cumin tea for reduction of stress.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Basil

Basil (also known as sweet basil) is the dried leaves of the herb Ocimum basilicum, a member of the mint family. It has a fragrantly sweet aroma and flavor (its botanical name is derived from the Greek “to be fragrant”). One of its components, methyl chavicol, is the major contributor to the herb’s flavor and aroma. According to its sensory profile, basil is characteristically tea-like, with green/grassy, hay-like, and minty notes. It is also slightly bitter and musty.

Egypt is the principal source of basil followed by the U.S. (mostly California). In 1964, the U.S. was importing 40,000 pounds of basil a year. Today, the annual import exceeds a million pounds. In addition, domestic production accounts for at least another 75%. Basil has a wide usage in tomato recipes, including spaghetti sauce, soups, and salad dressings, and the popularity of pizza and Italian foods continues to help fuel this “basil boom.” (Pizza has also helped out the consumption of another herb, oregano—imports of which account for 13 million pounds annually.)

Basil can be used in a number of dishes reflecting different regions of the country. Some examples include oils, cold sauces, and pesto for soups (Northeast); lobster bisque (South); and basil and bass terrine (Midwest). A search on the Web can also find a variety of recipes for basil ice cream, such as lemon-basil, jalapeño and tomato basil, and Thai basil with pineapple compote.

On the international front, basil is an important herb in Asian and Pacific Rim cuisine, finding its way especially in soups and sauces, and consequently may play an important role as foods from these areas fuse with other cultures.

Basil is also finding use in a number of newer, more innovative applications, including grilled vegetable sandwiches, veggie burgers, bakery desserts, and condiments such as herb butters and salsa.

Black Pepper

Derived from the dried berry (called a peppercorn) of a woody, climbing plant, black pepper (Piper nigrum L.) has a sharp, penetrating aroma, imparts a characteristic woody, piney flavor, and is hot and biting to the taste. (It has no relation to the pod peppers which include red and green pepper and the hot, red peppers.) A native of Indonesia, pepper is now cultivated in the tropics of both eastern and western hemispheres.

With the emphasis on hotter and hotter foods, it is not surprising that pepper remains so popular. According to ASTA, America’s black pepper imports were the highest on record in 1999—totaling more than 107 million pounds. Although 14 countries contributed to this total, three countries—India, Indonesia, and Brazil—accounted for 86% of it. Vietnam and Malaysia supplied most of the rest.

India provided more than half of the imports to the U.S. (57 million pounds). Termed Malabar, the Indian product is said to have a distinctive, fruity bouquet in its volatile oil and also tests high in non-volatile piperine (the bite factor). Indonesia, the second largest source, contributed Lampong black pepper which, compares favorably with the Indian product in pungency and flavor strength. Brazil, the third largest source, grows berries which have a distinctively smooth and very black outer skin and a creamy white center. (Brazil is also a major source of white pepper, which is produced by removing the dark skin and using only the core.)

In 1998, Vietnam was already the world’s second largest grower of black pepper. Although most of its output is going to Singapore and Europe, the U.S. bought 8 million pounds in 1999, and Vietnam holds much potential as a future source.

Oleoresin is the major extractive for black pepper because it yields both aroma and bite. It is usually added to a carrier to make it easily dispersible. The resulting soluble product may be liquid or dry

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Capsicums

According to ASTA’s “Spice Statistics 1998" report, consumption of the hot spices (black and white pepper, red pepper, and mustard seed) has increased 80% in the past 20 years. In 1998 alone, the hot spices accounted for 43% of the U.S. total spice usage.

America’s taste for heat is reflected in a recent statistic from Taco Bell. According to the fast-food chain, its customers reach for more spice (in the form of add-on sauce packets) 5.2 billion times a year. Of these, 2.6 billion are “mild,” 1.8 billion are “medium spicy hot,” and 800 million are “fire.” The American Tasting Institute recently named Kentucky Fried Chicken’s Triple Crunch Zinger sandwich (consisting of white meat chicken strips topped with a blend of fiery peppers and spices in a mayonnaise sauce) as its “Best of Show.” And a variety of spices and seasonings, especially the hotter types, were highlighted by exhibitors at the Chicago Section Suppliers’ Night. (See Ingredients section on page 68.)

Furthermore, foods may continue to get hotter or spicier for several reasons, including (1) the U.S. population is getting older and their taste buds will need to be challenged more; (2) the growing Hispanic segment will influence hotter dishes; (3) ethnic trends such as Caribbean, Mexican, and South America will provide impetus for this trend; and (4) new products in the grocery store are reflecting the same hot trend seen in restaurant menus.

If you want heat, the capsicums are the family to go to. Capsicum is a genus encompassing some 300 different varieties of plants producing fleshy vegetable pods. The property that separates this family from other plant groups is capsaicin, a crystalline substance that is extremely pungent. The higher the capsaicin content, the hotter the pepper. Major types of capsicums include paprika, red pepper, chili pepper, and chili powder.

According to ASTA, the worldwide capsicum crop currently exceeds 7.7 billion pounds annually and are now a much bigger spice in tonnage than pepper. India alone produces more than 2 billion pounds of capsicums a year.

The largest gains over the past 20 years have been registered by the hottest member of the group—red pepper. Red pepper is the dried, ripened fruit pod of Capsicum frutescens, one of the most pungent capsicums. Although there are numerous sources of red pepper, major producers are India, Pakistan, and China. Varieties originating from these countries are among the hottest and most pungent types.

In addition to providing heat, red pepper is playing an important role in a number of recent trends. For example, its heat may be combined with sweet flavors such as vanilla, maple, brown sugar, and fruit. In Hawaii, “Maui-Mex” is a style of cooking that combines sweet citrus fruit with red pepper for a sweet-heat result.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Ginger

Prepared from the dried rhizome or root of a tuberous perennial plant, Zingiber officinale, ginger has a flavor characterized by lemon/citrus, soapy, and musty/earthy notes. Available in ground and crystallized forms, the spice may be imported from countries such as India, China, Jamaica, and Australia.

The popularity of ginger in holiday foods was discussed in the November Ingredients section. But this appeal extends far beyond festive occasions, finding its way into a wide range of applications, such as sausages, baked goods, beverages, condiments, frozen desserts, pickles, and spice blends. For example, one new processed food product is Hellman’s Ruby Red Ginger Dressing.

What are some of the reasons for ginger’s popularity?

One reason has to do with its ability to work with other ingredients. ASTA describes the spice as “a silent partner,” quietly playing many parts. Recipes available from McCormick seem to support this point. In a mashed sweet potatoes dish, Ginger Thyme Sweet Potato Mash, ginger’s warm, citrus notes combine with the minty freshness of thyme. Or in a savory item, Hot Tempered Baby Back Ribs with Sweet Guava Glaze, the sweet flavors of brown sugar and guava jelly complement the heat that ginger, cinnamon, and crushed red pepper bring. Served with this item is a not-so-traditional cole slaw dish consisting of vanilla, ginger, red pepper, and black pepper—a mix which adds heat to the crisp texture of the salad. Because of this functionality, ginger plays an important role in international cuisines such as Asian, Australian, and Hawaiian, as well as creating new dishes that fuse different cultures.

In addition, studies are looking at its application in nutraceutical products. For example, ginger tea may be used to improve circulation, aid digestion, and treat nausea from motion sickness, pregnancy, or chemotherapy. Most recently, researchers at the University of Arizona Center for Dietary Supplement Research, established by the National Institutes of Health, are focusing on the use of ginger for the treatment of inflammatory diseases.

Rosemary

Rosemary is the dried leaves of the evergreen shrub Rosmarinus officinalis of the mint family. The small, narrow, aromatic leaves resemble curved pine needles when dried and are used as a fragrant seasoning herb. Major producers include France, Spain/Portugal, and the former Yugoslavia.

Rosemary has a distinctive pine-woody aroma with camphoraceous undertones and a fresh, bittersweet flavor. These qualities may work well with citrus flavors in both sweet and savory foods. For example, Lemon Rosemary Pound Cake —a recipe available from McCormick—offers a variation on the traditional bakery item. Crushed rosemary, used in the cake and glaze, is said to have a sweet, clean flavor which combines well with the cake’s citrus flavor.

A second recipe, Rosemary Mojo Lamb Chops, combines spices such as rosemary, thyme, basil, cumin, and black pepper with citrus juices such as orange and lime, and red wine.

According to ASTA, rosemary is considered one of the largest volume basic extractives (the others being anise, cinnamon, cloves, mint, nutmeg, and thyme). Rosemary is said to offer natural antioxidant properties, preventing lipid oxidation which can cause spoilage in edible oils and fat-containing foods as well as decrease product shelf life while accelerating color deterioration and rancidity. Rosemary extract may be used as a natural antioxidant in such products as sausage, fresh ground poultry, and frozen entrees. The essential oil contains 1,8-cineol, camphor, borneol, bornyl acetate, and alpha-pinene as primary components. The ingredient may be labeled “natural flavoring” or “spice extract.”

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Thyme

Thyme is the dried leaves of Thymus vulgaris, a small perennial of the mint family, native to southern Europe and Mediterranean area. Available ground or whole, it has a warm, pungent, sweetly herbal flavor.

If the word “pleasant” (not exactly the most scientific term, I admit) could be applied to any spice in this article, it could very well be thyme. A hint of thyme with its minty green flavor can enhance or provide balance to a variety of dishes. For example, the herb can be partnered with ginger’s warm, citrus-like notes or cinnamon’s hotter flavor; it can be combined with lime juice to create meat marinades; it can provide balance to the sweetness of fruits such as pears; it can be used with red pepper to create a sweeter heat; or it can work with garlic (but then for some people, anything works with garlic), especially in broths and sauces. Vegetarian dishes—vegetable, soy, and legume—are frequently seasoned with thyme. A sprig of thyme may also be used to enhance the appearance of a dish.

Today, Spain is the largest supplier of thyme to the U.S. Thyme is also grown commercially in California, where it is cultivated, machine dried and cleaned, and selected for rich color and flavor.

Thyme has also had a long history of medicinal virtues. Although much of this is folklore, it is interesting to note that thymol, the active ingredient in thyme oil, is still recognized today as a carminative, an anti-spasmodic, and a counter-irritant. The pharmaceutical industry uses a synthetic thymol now, but before it was developed, thyme oil was used in cough drops, antiseptic mouthwashes, liniments, and antifungal preparations. Because it has components which have antibacterial and antioxidant properties, it is quite possible that thyme may find a role in future nutraceutical applications.

Sesame Seed

Sesame seed—which comes from a tall annual herb, Sesame indicum, of the Pedaliacae family—offers a mild, sweet, nut-like flavor. Current imports show the U.S. relying on more than 20 countries for its sesame seed supply, including Mexico, Central America, and the People’s Republic of China. However, according to ASTA, if current varietal research is successful and machine harvesting can make the domestic product price competitive, U.S. has potential to be a strong sesame producer. Today, Arizona is the major grower in this country, with some production in Texas.

Americans reportedly consume more than 70 million pounds of sesame seeds a year—largely due, of course, to sesame-topped hamburger buns. Interest in ethnic foods and gourmet cooking is also boosting sales of such sesame products as halavah (Middle Eastern confection), tahini paste , and sesame salad oil. Also, sesame seeds are finding popular use in a variety of bakery and snack products. Recently, a leading pretzel brand, Snyder’s of Hanover, Hanover, Pa., launched a line of organic products, including Honey Wheat Sticks with Sesame Seeds.

Sesame seed’s 25% protein is rich in methionine and trytophan—two amino acids which are lacking in many other sources of vegetable protein. Consequently, when sesame flour is added to these other sources, they can become complete proteins, and find particular advantage in nutritionally balanced snacks such as breakfast bars and instant breakfast drinks.

In the U.S., sesame oil is considered a specialty salad and cooking oil—sold primarily through health and fancy food stores. There are two types—a coldpressed product which has a clear, golden color and bland taste, and an oriental type which is made by roasting the seeds before pressing. The oriental oil is dark colored and has a very strong flavor.

Sesame oil’s fatty acid composition contains about 45–50% linoleic acid. However, unlike other healthy oils which tend to oxidize easily, sesame oil has components which act as natural antioxidants. Sesame oil has been shown to lower cholesterol levels, inhibit and reduce cancer, and arrest the aging process in mice.

Loriva Supreme Foods, Inc., Ronkonkoma, N.Y., manufactures two types of sesame oil: a roasted variety, and a product derived from unroasted sesame seeds. The products are made by a cold-pressing process which delivers an alternative to traditional chemical extraction and refining methods which deprive the oils of essential nutrients. The process also captures the true flavor and natural aroma of each source. The manufacturer was recognized by the American Tasting Institute as the 1999 Gold Medal Winner for the “Best Line of Specialty Oils in America.”

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Coriander

An annual herb of the parsley family, Coriander (Coriandrum sativum) is available in three forms—whole and ground seed, dried and freeze-dried leaves (also called cilantro), and oil and oleoresin extractives.

Coriander seed reportedly has a flavor which resembles a blend of lemon and sage with a sweet note. Traditional suppliers of the spice were Morocco and Romania. However, according to ASTA, in 1999, Canada accounted for nearly 90% of U.S. imports, reaching 6.9 million pounds out of a total of 7.7 million. The Canadian product is mechanically harvested; it is very clean and is stored in silos for year-round availability. Most of this product is of the large seeded, lower-oil type. (Higher-oil seed, grown in Europe, is most frequently used for production of coriander oil and oleoresin.)

California is the major domestic producer of cilantro, the young leaves of the coriander plant. Cilantro has become especially popular in this country because of its use in Mexican and Chinese cuisine. Cilantro’s flavor, described as a mix of parsley and citrus, is said to be distinctively different from that of coriander seed.

Salsa, gazpacho, egg dishes, seafood entrees, black bean salads, Asian salads, and pasta and bean combinations are all big users of cilantro.

Essential oil of coriander seed is used today by distillers, soft drink manufacturers, picklers, and sausage makers. The oleoresin, which has a relatively high volatile oil content, is particularly suited to products that will be used in highheat processing and foods that will be microwaved.

Cloves

Cloves, said to be the strongest of all the aromatic spices, are the dried, unopened flower buds of Syzygium aromaticum, a myrtle tree. Most people are probably familiar with seeing them in baked ham and certain sweet pickles. However, they are used in a wide variety of spicing and seasoning combinations for sweet baked goods, sausages, luncheon meats, soups, salad dressings, relishes, and other foods.

In the case of clove buying, origin specifications are not very important, which is fortunate. In 1990, Brazil was U.S.’s largest clove supplier, accounting for 2,298,000 pounds or more than half of the U.S. consumption. In 1991, Brazil did not send a pound and has not been a major source since then. Currently, Madagascar supplies about 80% of the imports. However, Indonesia, which ceased being a source years ago (because the country used up its cloves in the making of cigarettes) is now becoming an exporter once again and may become an increasing source.

According to ASTA, volatile oil content is the essential quality factor in cloves, and as long as suppliers send product which consistently meets or exceeds 15% volatile oil, the location doesn’t matter. Instead, the customer specifies volatile oil percentage and various other analytical measurements, and the spice company meets the specifications from whichever source is currently available.

For uses where big, bold cloves are desirable (in pickling preparations, clove-studded hams, and certain casserole-type products), there is a grade called “hand-picked” which comes from Sri Lanka and Indonesia. “Handpicked” doesn’t relate to harvesting, but rather hand-selecting of the largest dried cloves (heads intact) to get the best-looking product.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Sage

Modern America is said to use more sage for seasoning than any other country in the world. The leaves of the sage plant (Salvia officinalis), a small perennial shrub of the Labiatae or mint family, are the source of this herb. The coastal areas of Croatia, Macedonia, and northern Albania produce the variety of sage preferred by U.S., and a supply of it reportedly remained available despite the recent war.

Sage is often associated with the holidays, especially its use in turkey and stuffing. However, according to the Foodwatch newsletter (July 2000), because of the growth in chicken recipes, sage has become more of an everyday flavoring and not just a holiday poultry seasoning.

Dill

The dill plant is an annual of the parsley family. Two of its components—dill seed and dill weed (the tops of the plants)—are used in the U.S. Dill weed, primarily grown domestically and in Egypt, is the dried leaves of the herb Anethum graveolens. Dill seed is primarily grown in India from a plant classified as Anethum sowa. Dill weed, said to be more subtle and fresh in flavor than the seeds, is characterized by sweet, green/grassy, tea-like, and rye notes.

Dill weed oil is mostly produced in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and western Canada. For this purpose, dill has been grown commercially in the U.S. for more than 30 years. Compared to dill seed oil, the weed oil has a sharper, cleaner, fresher dill flavor and one which doesn’t seem as oily. Principal contributor of the herb’s flavor and aroma is d-carvone.

Not too surprisingly, the pickle industry is the largest user of dill, primarily dill-weed oil. However, dill is popular in other foods, especially culinary applications, such as rubs, fish, vinaigrette, roasted vegetables, and sauces. Salmon and dill accounts for more than half of the appetizers using dill. A recipe available from McCormick, Purple Potato Salad with Dilled-Fennel Vinaigrette, combines toasted fennel seeds which release a mild and sweet licorice flavor with the fresh taste of dill to impart a new flavor dimension to potatoes, red bliss potatoes, and purple potatoes.

Unfortunately, dill is not associated with major ethnic cuisines such as Mexican/Latin or Asian, and for that reason increasing dill use is probably hampered somewhat.

Fennel

Fennel seed is the dried, ripe fruit of the perennial Foeniculum vulgare, a member of the carrot family. Once native only to the Mediterranean region, it is now grown primarily in India, China, Egypt, and Turkey. Fennel is generally described as having a sweet aromatic flavor and aroma similar to anise or licorice but less intense. It has a slight menthol undertone with musty/green flavor notes.

According to ASTA, the biggest use of fennel seed today is in Italian sausage, in which it supplies a distinctive, anise-like flavor and aroma. A large amount of this sausage meat is sprinkled on pizza, explaining why the consumption of fennel seed has more than doubled in the U.S. in the past decade. Fennel also goes into other sausages, such as pepperoni, cappicola, and Italian loaf, as well as fish preparations, curry powder formulations, Italian-type breads and baked goods, and sweet pickles. Fennel is an important ingredient in Latin-influenced cuisine and works particularly well with cumin. Sweet fennel oil may be used in liqueurs, candy, condiments,pickles, desserts, meat products, and a number of pharmaceutical preparations.

Fennel seed may be toasted and roughly ground to coat fish. For example, a recipe available from McCormick, Fennel Crusted Grouper with Vanilla Beurre Blanc, is grouper evenly coated in a mixture of toasted fennel seeds, black pepper, dill, and thyme. Served over the dish is a vanilla sauce combined with white wine, butter, shallots, and red pepper. The sweet vanilla sauce is said to complement the texture and heat of the crusted fennel.

Chefs are also using fennel to flavor foods ranging from rice-shaped pasta to portobello mushrooms. It may also be used in candied preparations for desserts.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Fenugreek

An annual herb of the bean family, Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) is cultivated in the Mediterranean area, India, and North Africa. It is said to have a bitter, maple-like flavor.

In India, the herb is incorporated into curry blend; it plays an important role in Middle Eastern dishes; and in the U.S., its extract may be used as a flavoring ingredient in imitation maple syrup.

Research studies have shown that it can help reduce cholesterol in laboratory animals, minimize symptoms of menopause, and lower blood sugar levels for diabetics.

Other Emerging Spices

The FoodWatch newsletter (July 2000) covered several other spices and herbs which are becoming increasingly popular and showing future potential.

For example, the growth and interest in ethnic foods has led to a more extensive usage of lemongrass, especially in Asian and Indian recipes.

Many leading culinary publications have written about lavender and its use in poultry, teas, ice cream, breads, cookies, lobster, and other uses. Although the recipes suggest that lavender may be used in a broad array of food products, its use still remains minimal.

Tarragon has a rich, sweet, anise-like flavor for use in sauces, dressings, seafood salads, and meat and poultry dishes.

Star Anise—the fruit of a small evergreen grown in China—is a major ingredient in 5-spice powder used extensively in Chinese cooking.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Ongoing Evolution of Spices

An article about a particular spice can cover a number of areas such as history, source of origin, differences between varieties, growing conditions, storage, handling, and so on. Although useful, that information, by itself, still gives an incomplete picture. That is because no one spice is consumed alone. Rather, the magic of spices is its relation to other spices, other ingredients, and the food it is used in. When a spice is combined with another spice, the resulting taste is very different from that of either spice individually. And even if the same spice combination is used in a variety of applications, the final taste will depend on what application—for example, savory or sweet, hot or mild—the combination is used in.

Now that point may sound very basic, but I think it needs to be stressed when considering the development of new flavors in the future. As the world grows smaller and different cultures come together, the opportunities for spice combinations creating new tastes become limitless. And ancient spices, when used in certain ways, suddenly become very young ingredients.

This point is also captured very well by the title of this article, which, of course, is meant to be an entertaining variation on the title of that classic movie, 2001: A Space Odyssey. In the movie, the word “odyssey,” on one level, means space travel. But on a higher level, it comes to mean man’s evolution from primitive ape to space traveler to a new species—a culmination of human and alien known as the “Star Child.” The story of spices is also an odyssey. On one level it can mean the different journeys that spices must take to reach our tables. These journeys are constantly changing as new sources are found and old ones replaced. On a higher level, however, the story of spices is an evolutionary one as well.

At one time, certain spices might be used to provide an incense in a temple. Or be used in a funeral ceremony. Or be given by a young lady to a knight as a sign of faithfulness. Or be revered as having mystical or healing properties. Furthermore, past cultures had to rely on spices they had access to, and so possibilities for new combinations were often limited. But as the years passed and we made advances in food science and technology, knowledge of individual cultures, and world travel, our use of spices evolved. For example, when you combine a hot spice with a sweet one, you create a new taste. When you use a spice in a not-so-traditional application, you create a new experience. When you prepare a spice in a different way, you create a different-tasting spice.

Of course, there is one important difference between the movie, 2001: A Space Odyssey and the story of spices. For all its greatness, the movie still remains science fiction. But there’s nothing science fiction about the spice developments discussed in this article.

Donald E. Pszczola, Associate Editor