Intelligent Packaging Improves Chilled Food Distribution

PACKAGING

In previous columns, I have written about active and intelligent packaging, and of the inevitability of intelligence in packaging eventually leading to monitoring and control. And I have asserted that the programs presented by IFT’s Food Packaging Division (FPD) at the 2001 IFT Annual Meeting were at the cutting edge of food industry commercial practice. I supported that assertion with a promise of more information on the subject. Here it is.

At the FPD symposium in June, Fred Reimers, veteran food safety manager of H-E-B Food & Drug Co., a major retail supermarket chain headquartered in San Antonio, Tex., described a means to control temperature in retail distribution—an area that has been repeatedly identified as a significant deficiency in our entire food distribution chain. As every food technologist should know, food deterioration is linked to temperature. Chilled foods, and especially today’s “chef-quality” prepared chilled foods, and fresh meats, fish, and dairy case contents are especially vulnerable to the increases in microbiological growth, enzymatic and biochemical reactions, and physical action rates resulting from increased temperature.

At the FPD symposium in June, Fred Reimers, veteran food safety manager of H-E-B Food & Drug Co., a major retail supermarket chain headquartered in San Antonio, Tex., described a means to control temperature in retail distribution—an area that has been repeatedly identified as a significant deficiency in our entire food distribution chain. As every food technologist should know, food deterioration is linked to temperature. Chilled foods, and especially today’s “chef-quality” prepared chilled foods, and fresh meats, fish, and dairy case contents are especially vulnerable to the increases in microbiological growth, enzymatic and biochemical reactions, and physical action rates resulting from increased temperature.

Despite the Food and Drug Administration’s 1999 Food Code (recommendations for five years from now) that foods be maintained at temperatures of 41°F (today, 45°F is acceptable) at the “warmest” location, including the defrost cycle, this “suggestion” is hardly adequate. Data assembled in numerous articles and research papers, most vocally by Hospitality Institute of Technology and Management’s Pete Snyder, demonstrate this inadequacy. The difference between a nearly ideal 31°F and the 41°F recommendation is 10°F, a driver that increases deterioration rates by a factor of 1.5–2. FDA is now proposing that time should also be included in the temperature equation—a good idea, if followed. And, as publications by Audits International’s Richard Daniels clearly indicate, temperatures of food in United States distribution channels are more probably in the range of 45–55°F, well out of the range of ensuring microbiological safety and quality retention.

Thus, we are faced with a distribution system that is largely unregulated, whose standards are recommendations rather than mandated, and that is generally out of control and not well managed, at a time when the volume of refrigerated product in the chain is increasing dramatically.

Reimers pointed out in his presentation that consumer demand for packaged, safe, fresh, “restaurant-quality” meats and freshly prepared foods reflects the changing supermarket landscape. At a time when more and better refrigeration and temperature control are needed to meet consumer food desires, “economics” and a paucity of information on the benefits of good temperature control dominate. One consequence is that conservative practices dictate very short production runs and discarding of food within one or two days of preparation and/or packaging to avoid temperature-driven adverse effects. This is not to say that many links in the food distribution chain are not well controlled. Most, however, are not under good control, and this, many observers believe, leads to unduly high costs for food.

Harvard University’s Leonard Schlesinger asserted, “Virtually every . . . innovation in the supermarket industry in recent years can be traced to an initiative begun at H-E-B.” Might this Texas chain lead to a real reexamination of the realities and benefits of temperature control?

Reimers’ presence on the FPD platform was supported by his stated definition of packaging as “a protective unit for storing or shipping a commodity.” H-E-B involvement in this context is overt measurement and control of packaged food within the retail environment, an extraordinary practice even in 2001. At H-E-B, everyone involved, from top management down to store staff, is overtly committed to safe food and handling, including temperature control.

Thermographic imaging of food within display cabinets offers rapid assessment of the actual temperatures of the food mass—as contrasted to the more common measure of air temperature at the coil discharge. Without even considering the vast gap between air and product temperature, what happens to the food temperature during the usual twice-a-day defrost cycles? And what happens when, as occurs all too frequently, coils are covered with ice? Reimers’ examples suggested an enormous temperature disparity between products in proximity with each other.

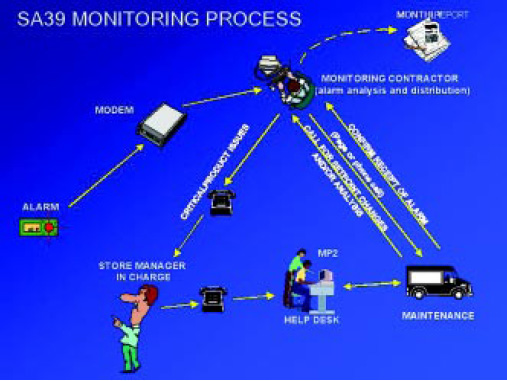

H-E-B has installed an elaborate system to measure, monitor, and control food temperatures within each element of the store. In addition to the usual indicating digital thermometers in each location, the measurements are sent to a central computer where the temperatures are recorded and, more important, monitored for control purposes. Air temperatures within each chilled food area are reviewed by the computer against a reference, and someone is alerted to take action—an almost revolutionary concept in chilled food logistics.

But H-E-B strides a giant step beyond: within each area is an artificial product sensor. A simulated package (cleanable, waterproof, portable) containing a temperature transducer is installed in the “warmest” location within each case to reflect the temperature of typical chilled foods and to transmit its data to a central computer. When the temperature is outside the mandated boundaries, mechanical alarms signal the deviation for human intervention. The notion of protection against product abuse has been advanced significantly. Records of the inputs are available to all members of the H-E-B monitoring team.

Unfortunately, the artificial product still does not measure the temperature situation in fresh meat, fish, or delicatessen packages—a large volume sector usually made on premises. Attempts to incorporate simulators for back-room-packaged foods to date have resulted in too many false positives. Insertion probes in product or return air are currently mandated in these sensitive areas.

Installation of such temperature controllers reduces costs, saves energy, helps to comply with existing and pending regulations and guidelines, and definitely aids in food safety. It represents true energy management.

According to Reimers, the monitoring system has resulted in improved food safety, reduced shrink, a tool in the front line of defense, an integrated flexible and simple system tied to a central system, and temperature data that can be used in place of surveys to protect the package. It can perhaps be considered a tertiary packaging level, in professional packaging parlance.

Tomorrow offers the possibility of both alarm and data collection over the World Wide Web; real-time and archived data viewing; microbiological growth based on temperature–time experience signaling; and shelf life prediction. On-package time–temperature integrators have been commercially available for many years, but their expense and need to be directly read represent obstacles to widespread use. Time-temperature measurement and integration are quite feasible through intelligent packaging, the incorporation of radiofrequency responders, and even transmitters. The time–temperature signals directly from real, not artificial, packages may be electronically linked to the distribution-system monitoring software to provide instant readings on the status of the contained food. Even consumer checkout scanner readings may offer information on the quality and safety of any single package.

Visionary Reimers concluded that temperature monitoring is a form of packaging to protect the product that can be integrated into other distribution systems to provide tangible benefits. Temperature management holds the potential for not only managing food safety but also enhancing quality through shelf life prediction. This H-E-B professional has charted a route by which the difficult task of controlling the safety and quality of case-ready fresh meat, fresh fish, and home-meal-replacement foods may be facilitated. It is another exciting prospect for food packaging in its complex role as a foundation stone for food science and technology.

PRODUCTS & LITERATURE

Polyethylene Bottle in a 10-oz size is being used by Welch’s for its Concord and Niagara grape-based single-serve products, including 100% juices, juice cocktails, and juice drinks. The lightweight, resealable, and shatterproof bottle was recently introduced nationally to wholesale membership clubs and is being distributed this month to vending, foodservice, mass merchandise, and grocery store channels. Welch’s is the first major brand to introduce this size plastic bottle for juices. For more information, contact Welch’s, P.O. Box 9101, Concord, MA 01742-9101 (phone 978-371-1000, www.welchs.com) —or circle 319.

Silicone Insert for wine bottle corks prevents the wine from taking on unpleasant flavors from the natural cork. It prevents diffusion of undesirable molecules into the wine. The insert is impermeable to liquids and undesirable aromatic molecules but permeable to gases such as carbon dioxide and oxygen. Inserted at the base of the cork in a suitable cavity, it prevents contamination of the wine while allowing it to “breathe,” a process of oxidation that makes wine smoother to drink. For more information about the “Preserver” insert, manufactured by Cortex, a joint subsidiary of two French wine cork manufacturing companies, contact the French Technology Press Office, 1 E. Wacker Dr., Suite 370, Chicago, IL 60601 (phone 312-222-1237)—or circle 320.

Bottle Labeling System, Model 5000, features a vacuumized reverse-feed wrap belt that allows fast and accurate full-body or front-and-back placement of pressure-sensitive labels on almost any cylindrical glass or plastic container. It also handles paper and film labels. For more information, contact Label-Aire, Inc., 550 Burning Tree Rd., Fullerton, CA 92833 (phone 714-441-0700, fax 714-526-0300, www.label-aire-inc.com) —or circle 321.

Digital–Mechanical Packaging Equipment combines the best features of digital pneumatic and analog mechanical equipment. Models PXM-1, 2, and 3 are available in the Pre-Formed Containers Fill, Seal, and Cap line, with a new modified-atmosphere system, room for up eight fillers, and an output of 40–160 containers/min. Models PDP-4.1 and 4.2 are available in the Stand-Up Pouches Fill and Seal line, with room for two fillers and output of 25–50 containers/min. Model PFM-1 is available in the Bottles and Jugs Fill and Cap line, with room for up to four fillers and an output of 30 bottles/min. For more information, contact Pack Line Corp., 26001 Miles Rd., Unit 6, Cleveland, OH 44128 (phone 216-464-2828, fax 216-464-2829, www.packlinecorp.com) —or circle 322.

Rotary Pocket Unscramblers for plastic containers feature self-adjusting rotary pockets that gently pick up and cradle each container and set them precisely in line. Unscramblers are available with a maximum of 8, 15, or 20 rotary pockets arranged in carousel fashion for production speeds of 40–400 containers/min. For a 4-p brochure describing the RP Unscramblers, contact Omega Design Corp., 211 Philips Rd., Exton, PA 19341-1336 (phone 610-363-6555, fax 610-524-7398, www.omegadesign.com) —or circle 323.

Aseptic Filling Lines for beverages and dairy products feature an injection system with magnetic control, enabling the filling of both liquid and semiliquid products. Because containers are transferred by their neck, it is quick and easy to adjust settings to accommodate varying container sizes and shapes. The lines accept PET, barrier PET, Barex, and HDPE containers. The SAS 2 IN line is designed for packaging high-acid products (pH < 4.5), such as fruit juices, fruit drinks, flavored teas, and isotonic beverages. The SAS 2 TF line is designed for packaging acidic and neutral products (pH $4.5), such as UHT milk and other milk drinks, coffee, and unflavored tea. For more information, contact Serac, Inc., 300 Westgate Dr., Carol Stream, IL 60188 (phone 630-510-9343, fax 630-510-9357, www.seracgroup.com) —or circle 324.

by AARON L. BRODY

Contributing Editor

Managing Director, Rubbright•Brody, Inc.

Duluth, Ga.