Developing and Marketing Foods for Diabetics

Designer Foods for Diabetics: A Big Potential, Tricky Market

A whole new category of foods is emerging to help battle the onslaught of diabetes, but how they are marketed has an important bearing on their success.

"We have created the great American feedlot.” So says Walter Willett of the Harvard Medical School of Public Health in an August 24, 2002, Time Magazine Health story about the growing plague of obesity in the United States. “Sedentary lifestyles and a cornucopia of food have transformed people into the equivalent of corn-fed cattle confined in pens,” Time’s editors conclude in the same article.

These observations come amid an increasingly heated public debate over the causes and cures of obesity and its deadly side effects, mainly diabetes, the seventh-leading cause of death in the U.S., according to the American Diabetes Association (ADA). Much of the debate centers on food companies, with the fast-food industry the most popular scapegoat.

A Scapegoat for Obesity

Industry leader McDonald’s is the target for two well-publicized legal actions in which persons suffering from obesity blame the company’s food and marketing practices for their condition. The most recent action came in September, when three New York City teens filed a class-action lawsuit against the company, alleging that its food caused them to gain as much as 200 lb and develop serious health problems, including diabetes. According to court papers cited in the Washington Times, the teens allege that McDonald’s inaccurately posted nutrition information and deceptively advertised its products. The attorney for the teens, Samuel Hirsch, stated that his clients ate at the restaurant almost every day for at least five years. McDonald’s spokesman Walt Riker in a written statement called the suit “frivolous.”

Earlier this year, a New York City man, Caesar Barber, filed suit with the Supreme Court of New York against McDonald’s and three other fast-food companies, in which he claimed that the restaurants were responsible for making him and others overweight and at risk of illness. Hirsch also represents Barber.

These actions, while seeming to epitomize a highly litigious society in which personal responsibility has given way to wholesale victimization, actually serve to focus and intensify media attention on the broader issues. They also serve as a bellwether for trial lawyers looking for a sequel to the lucrative era of tobacco-related class-action litigation.

“There has been a huge increase in the number of stories about obesity in a very short period of time,” stated Sylvia Rowe, President of the International Food Information Council, during her presentation at the Hot Topic session on obesity at the Institute of Food Technologists’ Annual Meeting in June. “The topic makes for very compelling visual coverage.”

So do the statistics. Approximately three of every five U.S. adults is overweight or obese, at an economic cost due to increased health care and lost productivity of $117 billion a year by some estimates. The death toll for obesity-related deaths is 300,000 per year and rising, Rowe said. Obesity is rapidly supplanting tobacco use as the leading cause of preventable death in the U.S., and diabetes is at the root.

Type 2 diabetes is most closely associated with obesity, with statistics for both rising in steep tandem lines. About 5.9% of the U.S. population has been diagnosed with some form of diabetes, mostly Type 2, as reported by Linda Milo Ohr in the September 2002 issue of Food Technology. Up to 20 million more may have an undiagnosed condition. ADA estimates that the number of diagnosed diabetics will grow by 798,000 within a year and continue to accelerate.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

A New Market Segment

While the finger-pointing intensifies over who’s to blame and what to do about it, the role of food is incontrovertible. It can play a negative or positive role. In fact, the diabetes epidemic has created a new market segment for specialized foods. A whole new category of foods is emerging to help battle the onslaught of diabetes. Foods designed for diabetics are different from the low-sugar, low-fat foods often found on recommended lists. These specifically formulated foods consist primarily of nutrition bars and shakes engineered to provide therapeutic balance and work in conjunction with drugs to help control blood glucose levels more efficiently.

One of the first brands, launched in 1995 to address this need, is Choice DM®, from Mead-Johnson Nutritionals, Evansville, Ind. It currently offers two flavors of nutrition bars and two varieties of shakes in single-serve cans. An oatmeal product was dropped from the line in March.

Mead’s experience illustrates the complexity of this seemingly hot retail segment. Choice DM is sold through several distribution channels, including fulfillment companies that send drugs and supplies directly to the home, health-care agencies, institutional distribution to hospitals, clinics, and nursing homes, and conventional retail sales. Retail has the most volume potential, but the environment is highly competitive. Choice DM and similar “disease-specific” foods are relegated to the pharmacy, where diabetics spend a considerable amount of time purchasing drugs and supplies. When it comes to food, however, they shop like everyone else—often making purchases for the whole family. Thus, the greatest potential for shakes, bars, and cereals is positioning where these products normally appear. Retail shelf space, however, is extremely valuable, and with supermarkets operating on razor-thin margins the turnover must be high. This precludes products that are aimed at a specialized consumer segment, even one as large as diabetics.

This economic reality was partially to blame for the demise of Choice DM cereal. “It was an excellent product, we just had a hard time getting distribution,” stated Choice DM brand manager Kirsten Lemmon. “It seems like retailers are not ready to put foods for people with diabetes in general grocery, and consumers weren’t used to looking for food in pharmacies. I think we were ahead of our time with that product.”

Another challenge is reaching the growing population of diabetics. “We are experimenting with different channels. Anywhere we can reach a population with diabetes, we want to be there,” Lemmon stressed. The most effective means today is through health-care professionals, who are generally enthusiastic about foods that can help diabetics better manage their blood chemistry.

“I see a real niche for these products,” stated Anne Wolf, a registered dietitian and research instructor at the University of Virginia School of Medicine. “Right now, many people are confused by the various educational materials they get, with instructions for diet. They get stuck on certain food intake and sometimes go back to their normal diet. These products can help them get the most from their diabetes medication.”

In addition, Mead is assisting in efforts by ADA and various health organizations to sponsor diabetes-screening programs. Many such programs are held in supermarkets, such as “Diabetes Corner,” introduced last year by Nash Finch stores, a 44-unit chain based in Minneapolis, Minn. The program includes screening, product merchandising, a newsletter, and periodic in-store activities. Much of the retail space is devoted to food products such as sugar-free pancake mixes, syrups, and jellies.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

A similar program was initiated by Giant Food, Landover, Md., which is initiating wellness centers focusing on the needs of diabetics in many of its stores. “The present and future of diabetes care is going to come from trying to help people where they are—in the homes, through the TV and the Web, in schools, in churches and community centers, in supermarkets, pharmacies, etc.,” stated ADA Vice President of Clinical Affairs Nathaniel Clark in an interview with Supermarket News.

Retailers also have become more involved in community organizations. Penn Traffic, Syracuse, N.Y., which operates Big Bear markets in the Northeast, is active with local chapters of the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation and ADA. Safeway stores and 40 other retailers representing 21,000 stores nationally joined forces last summer in a diabetes educational program targeting women. The program, called “Take Time to Care,” recognizes that 60% of the population afflicted with diabetes is female, according to Supermarket News.

Also behind similar efforts are several large food companies. The Kraft Foods unit of Philip Morris Cos. has a Web site dedicated to diabetic recipes, and Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., sells its own line of diabetic products through its in-store pharmacy. These products, however, are primarily sugar-free alternatives, not functional foods. In addition, ADA has a virtual grocery store on its Web site to foster education and allow food companies to sponsor virtual aisles and displays. Participants include Keebler Foods’ Murray Sugar Free Cookies, Monsanto’s Equal sweetener, Kraft cheese, Ocean Spray, Inc., and Abbott Laboratories, whose Ross Products Div. markets Glucerna® nutrition bars and shakes.

Among these brands, only Glucerna is specifically designed for blood glucose maintenance. Since it is a part of the Ensure product line, Ross Products is positioning the brand in familiar retail territory, with other nutritional supplements.

The newest player among foods designed for diabetics is Victus, Inc., based in Miami, Fla. In August, it launched Enterex Diabetic with Fiber beverages. Other products in the market include Balance Bars, from the Balance Bar Co., Extend Bar from Clinical Products, Ltd., NiteBite Timed Release Glucose from ICN Pharmaceuticals, and Level Best beverages from Functional Foods, Inc.

A Role in Diabetes Management

For the most part, these designed foods are rich in protein, complex carbohydrates, and fiber, with little or no saturated fat or sugar. They also are fortified with essential vitamins and minerals and often backed by clinical and consumer tests to support their efficacy. This enables them to assume a role in diabetes management far greater than conventional no-sugar foods. “If you have better blood sugar control through a dietary product, then some people may not need certain medications, which often number up to three,” Wolf said.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

For its part, ADA stated in its January 2002 Diabetes Spectrum that “The complex formulation of the diabetes bars and beverages on the market responds to the mounting evidence that certain nutrients and physiologically active food components play a role in improving glycemic control and reducing risk factors for development of diabetes complications.”

Adding fuel to this expanding market is a shocking rise in childhood diabetes. ADA estimates that up to half of new diabetes cases in children are diagnosed as Type 2, considered extremely rare a generation ago. Like the adult population, childhood diabetes is statistically linked to a surge in obesity. The number of overweight children in the U.S. has increased by 50% since 1991.

“It’s definitely a population we’re going to have to take a serious look at,” stated Mead’s Lemmon. “The key is fitting the products into their lifestyle. Being where they are—in vending machines or at sports activities—is critical. Teens are less likely than adults to be culled out as different.”

Collectively, these trends provide significant momentum for the new category of foods specifically developed for diabetics. With supermarkets increasingly promoting screening activities, and health professionals seeking better and more-effective glucose-management tools, these specialized foods are well positioned for expansion.

“We don’t have any frozen foods for diabetics. We need a combination platter of food that really watches the amount of carbohydrates and really makes sure the protein is good,” Wolf observed, adding that breakfast also is important. “It’s a critical meal, because if your blood sugar can stay stable during breakfast time, it’s pretty good for the rest of the day.”

The future may be characterized by innovative partnerships, such as Mead joining forces with Quaker to reintroduce a line of breakfast foods and then leveraging Quaker’s presence in the cereal aisle to gain shelf space. Or Nestlé’s Stouffer’s brand partnering with Ross Labs to create a Lean Cuisine D line, addressing the need for a combination platter. This is speculation at present, but Lemmon admits, “We’re always looking for opportunities.”

by Pierce Hollingsworth,

Contributing Editor

The author is President, The Hollingsworth Group, P.O. Box 300, Wheaton, IL 60189.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Formulating Foods for Diabetics

Here’s how Mead Johnson Nutritionals developed its Choice DM line of retail food products designed specifically for persons with diabetes.

Diabetes is a serious and increasingly common disease. Approximately 17 million Americans are afflicted with it, and another 16 million with a condition called pre-diabetes, according to the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

In diabetes, the body does not produce enough and/or properly use insulin, the hormone that is needed for sugar, starches, and other food to be utilized for energy. Sugar, in the form of glucose, is the basic fuel for the body, and insulin is necessary for its transportation from the blood to the cells. High levels of glucose in the blood can cause numerous medical problems, including heart disease, stroke, kidney failure, blindness, and neurological disorders.

There are two major types of diabetes. Type 1 diabetes, in which the body does not produce any insulin, occurs most often in children and young adults and accounts for 5–10% of cases. Type 1 diabetics must take daily insulin injections.

Type 2 diabetes, in which the body does not make enough or properly use insulin, accounts for 90–95% of cases. According to Nathaniel Clark, ADA’s National Vice President for Clinical Affairs, Type 2 diabetics can live long, healthy lives by keeping their blood sugar level within their target range through proper meal planning, exercise, and weight control. The Association’s philosophy is that people with diabetes can eat the same foods that everybody else eats, he said. The Association doesn’t have a problem with the availability of foods specifically tailored for people with diabetes, he added, but it doesn’t promote their use.

Nevertheless, although people with diabetes can control their diets using regular foods, various formulated foods are being developed specifically for them. Sugar-free and fructose-sweetened candies—such as Hain Celestial Group’s Estee™ products—have been marketed to diabetics for a long time, but foods developed specifically to help people with diabetes manage their diets are relatively new. The two most visible brands have been the Choice DM® line of products marketed by Mead Johnson Nutritionals, Evansville, Ind., and the Glucerna® line of shakes and snack bars marketed by Ross Products Div. of Abbott Laboratories, Columbus, Ohio.

I discussed the development of the Choice DM line with Steve Rumsey, Director of Scientific Research at Mead Johnson Nutritionals.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Four Products Developed

Recognizing the opportunity for retail products designed to fit into diabetics’ meal planning, he said, the company, which has a long history of providing nutritional products for patients with a variety of health problems, decided to develop four types of products—liquid beverages, snack bars, nutrition bars, and instant hot cereal—for the retail market, in addition to liquid tube-feeding products for the clinical and hospital market.

• The Ready-to-Use Beverage (as well as the liquid tube-feeding products) was introduced in 1995. It is a nutritionally complete liquid beverage—four cans provide 100% of 24 essential vitamins and minerals, including antioxidants and fiber—for flexibility in diabetes meal planning. The product has been clinically shown to result in lower blood glucose response than standard nutritional supplements, such as Ross Products’ Ensure, the leading nutritional supplement. It provides 40% of total calories from carbohydrate and about 68% of the calories from carbohydrate and monounsaturated fat. It also contains added antioxidants vitamins C and E. The beverage is marketed in Vanilla and Chocolate flavors in 8-fl-oz cans, sold individually or in multipacks of 6 cans. Each can provides 24 g of carbohydrate and 220 kcal and can be used as a snack or as part of a small meal.

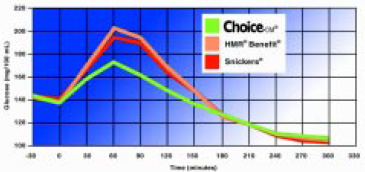

• The Nutrition Bar was added in 1997. The chocolate-covered bar has a nougaty, chewy texture and is very similar in nutrient composition to the beverage, providing 140 kcal, 6 g of protein, 4.5 g of fat, and 24 vitamins and minerals per 1.23-oz (35-g) bar. It contains a proprietary blend of carbohydrates that results in a special starch that is resistant to digestion, enabling the product to provide a lower glycemic response than a product with equivalent carbohydrate levels. Resistant starch isn’t used in the liquid beverage because heat used in processing the beverage would denature the starch and cause the product to gum up. The bar is comparable in nutrient composition to the Glucerna bar and lower in glycemic response than Health Management Resources Corp.’s HMR Benefit® snack bar and a Snickers® candy bar (see chart). It is sold in Peanutty Chocolate and Fudge Brownie flavors individually and in multipacks of 4 bars.

• The Nutrition Bar was added in 1997. The chocolate-covered bar has a nougaty, chewy texture and is very similar in nutrient composition to the beverage, providing 140 kcal, 6 g of protein, 4.5 g of fat, and 24 vitamins and minerals per 1.23-oz (35-g) bar. It contains a proprietary blend of carbohydrates that results in a special starch that is resistant to digestion, enabling the product to provide a lower glycemic response than a product with equivalent carbohydrate levels. Resistant starch isn’t used in the liquid beverage because heat used in processing the beverage would denature the starch and cause the product to gum up. The bar is comparable in nutrient composition to the Glucerna bar and lower in glycemic response than Health Management Resources Corp.’s HMR Benefit® snack bar and a Snickers® candy bar (see chart). It is sold in Peanutty Chocolate and Fudge Brownie flavors individually and in multipacks of 4 bars.

• The Crispy Bar was added in 2000 but was discontinued earlier this year for marketing reasons rather than product shortcomings—basically, people do not look for foods in the pharmaceutical section, and shelf space is very difficult to obtain in the regular food sections of supermarkets for a product intended for a small population. The 1.06-oz (30-g) snack bar contained soy nuggets to provide a crispy texture. It was not designed to be nutritionally complete, but it did provide 110 kcal, 4 g of protein, and essential vitamins and minerals and had been clinically shown to result in a lower blood sugar response than other snack bars tested. It was sold in Berry Almond and Peanut Butter flavors.

• The Hot Whole Grain Cereal was introduced in 2000 but also was discontinued earlier this year for the same reason as the Crispy Bar. The instant hot oatmeal type cereal used a proprietary blend of specific strains of oats and barley designed to release carbohydrates slowly and help keep blood sugar levels on an even keel. It provided a lower glycemic response than the leading Quaker instant oatmeal. The product was marketed in Vermont Maple and Apple Cinnamon flavors, in boxes containing six 1.4-oz (40-g) packets.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Challenges in the Development

The object in choosing the name Choice DM, Rumsey said, was to indicate that the product would give people with diabetes choices to help them manage their daily diet by producing a measurably lower glycemic response. The DM in the product name, he added, was chosen to represent the role these products play in dietary management.

The company conducted many focus group interviews and found that the participants felt that products like these would make choices a little simpler for people with diabetes. They also felt that having a company like Mead Johnson with a long history of providing nutritional products for infants and adults gives the consumer confidence in these products.

Many of the products on the market for people with diabetes are just sugar-free products, with no fortification, Rumsey said. They provide no glycemic response but also no nutrition. It would be relatively easy to simply substitute artificial sweeteners for carbohydrate sweeteners, he said, but the real challenge is to provide nutrients—carbohydrates, protein, fat, vitamins, and minerals—while minimizing the glycemic response.

This is especially important if the products are to be used in a hospital-care setting or as a meal replacement, providing sustained nutrition for someone. We want well-balanced macro- and micronutrient profiles, he said.

The first step in formulating the products, Rumsey said, was to screen potential ingredients, using literature values, in-house assays, and finally in-vivo studies looking at combinations of ingredients. The target was to achieve a significantly lower glycemic response than comparable products, using the standardized glycemic response test. The test substance is provided to people with diabetes in a measured dose of 50 g of carbohydrate, and the rise in blood glucose level and insulin level over time is measured and compared to a standard. Some studies use glucose as the standard, he said, while others use white bread. The response from glucose is a little higher than that from white bread, but the results are comparable.

The rationale for developing the products, Rumsey said, was to create products for people with diabetes that would satisfy their nutritional needs, following the American Diabetes Association’s Medical Nutrition Therapy guidelines, i.e., to aid individuals in maintaining better blood glucose control, as well as help them control blood lipid levels. To that end, the products were designed to provide relatively lower glycemic response than comparable food products and higher monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acid levels than regular alternatives, while maintaining low saturated fat levels.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

The goals were achieved in different ways for the different types of products. For the beverages, the company used a unique blend of canola oil, corn oil, and sunflower oil to provide a high monounsaturated fatty acid composition, plus a blend of simple sugars and long-chain maltodextrins with fat and protein to provide a lower glycemic response. The resulting product had a glycemic index of 50, compared to 100 for glucose, about 25% lower than Ensure, another complete nutritional beverage.

Because of its potential use in clinical and hospital settings, a primary strategy was to make the beverage nutritionally complete—capable of sustaining life—by fortifying it with all essential micro- and macronutrients. The product was also designed to have a high level of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids to make it heart-healthy. Because the company had had a lot of experience in formulating fortified beverages, such as the company’s nutritionally complete Boost® energy drink for the general population, the formulation challenges were not significant.

One of the challenges the company faced was to make the products taste good. Taste is foremost at Mead Johnson, Rumsey said, because if people don’t like the taste, they won’t use the product and won’t reap its nutritional benefits. The company generally works with outside flavor houses, as well as its own in-house flavor group, conducting internal panels and studies to refine the products.

The main challenge in using resistant starch in the nutrition bar was to prevent the product from drying out, Rumsey said. The company successfully prevented that by using various combinations of carbohydrates to keep moisture in the product. A unique encapsulation technology helps keep moisture from migrating within the product from ingredient to ingredient.

One last challenge—perhaps the most important one—is marketing the products, the topic of Pierce Hollingsworth’s companion article, “Designer Foods for Diabetics: A Big Potential, Tricky Market,” in this issue (p. 38). An important consideration in marketing foods for people with diabetes, Rumsey said, is where the products are displayed for sale. Most Choice DM products are sold in the pharmacy section of supermarkets, mass merchandisers, and drug stores where other diabetes products are sold, and that’s probably not where they are looking for foods, he said.

In the meantime, as Linda Milo Ohr reported in her article, “Catching Up with Diabetes,” in the September 2002 issue of Food Technology (p. 87), research is being conducted on a number of substances, such as chromium and biotin, that may have an effect on blood glucose levels and help the body respond to insulin and that may eventually, if not already, appear in formulated foods designed for people with diabetes.

by Neil H. Mermelstein,

Editor