Dairy Derivations

NUTRACEUTICALS & FUNCTIONAL FOODS

Dairy Derivations

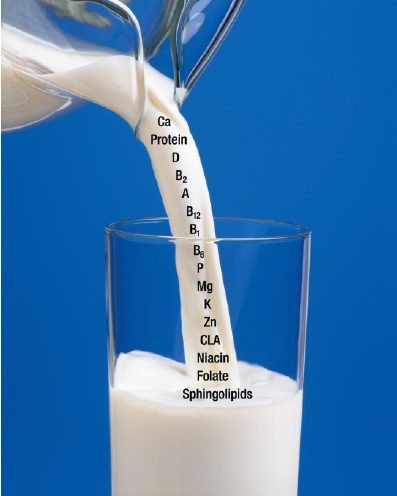

It is no question that dairy products are essential for proper nutrition. Dairy foods such as milk, yogurt, and cheese constitute an integral group of the Food Guide Pyramid. Both the pyramid and National Dairy Month (June) encourage consumers to obtain 2–3 servings of dairy products each day.

The American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Dietetic Association, and National Medical Association help promote dairy food consumption by supporting the 3-A-Day of Dairy program. The campaign, sponsored by the American Dairy Association/National Dairy Council, encourages Americans to eat at least three servings of calcium-rich milk, cheese, or yogurt every day to help address America’s growing calcium deficit.

In addition to promoting stronger bones and teeth, research has associated the intake of dairy foods with weight loss and blood pressure control. Dairy foods such as milk and cheese have also been shown to help prevent dental caries by reducing the effects of acids formed by plaque bacteria and restoring the enamel that may have been lost while eating (Kashket and DePaola, 2002).

So dairy products such as milk not only “do a body good,” they also serve as a source of healthy ingredients for formulators to utilize in functional foods. Dairy-derived nutraceuticals such as whey protein, calcium, and conjugated linoleic acid have been linked to preventing cancer, hypertension, obesity, and more. This column will discuss some of these ingredients and their reported benefits.

Whey Protein

Whey, a by-product of cheesemaking, contains lactose, minerals, vitamins, protein, and traces of milkfat. Whey proteins are especially popular in sports nutrition products such as bars and beverages because of the essential amino acids they supply. They have a high content of sulfur-containing amino acids that support antioxidant functions and branched-chain amino acids that help minimize muscle wasting.

The Dairy Products Technology Center at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, works on developing prototypes using whey protein concentrates and isolates. Examples include a high-protein chocolate chip cookie and a high-protein energy bar using whey protein concentrates, and a smoothie mix using whey protein isolate.

Whey proteins are also utilized in some infant formulas. For example, Nestlé’s Carnation® Good Start® utilizes whey protein that the company says is partially hydrolyzed for easier infant digestion. According to information from the U.S. Dairy Export Council, an active area of research related to whey and infant nutrition is the formation of biologically active peptide sequences during digestion and resultant effects on secretion of entero hormones as well as immune enhancement. In addition, a whey-predominant protein was found preferable to a casein-predominant protein in the diet of very-low-birth-weight neonates, possibly because it may lessen the risk of metabolic acidosis and its potential adverse effects.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

In addition to sports and infant nutrition, a whey protein isolate has also been linked to hypertension (Pins and Keenan, 2002). Davisco Foods, Eden Prairie, Minn., presented research on its BioZate® 1 hydrolyzed whey protein isolate supplement and hypertension at the 11th International Congress on Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy last May. Researchers in the Dept. of Family Practice and Community Health at the University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, hypothesized that this whey protein isolate might inhibit the angiotensin-converting enzyme and thereby lower blood pressure. They hypothesized that a 20-g dose would significantly reduce both systolic (7 mm Hg) and diastolic (4 mm Hg) blood pressure.

Thirty unmedicated, nonsmoking, borderline-hypertensive men and women were randomized to the hydrolyzed whey protein isolate group or the unhydrolyzed whey protein isolate control (BiPRO®). Individuals were instructed to take their protein dose daily with water for six weeks and to maintain their normal lifestyle habits. Participants reported weekly in the early morning for blood pressure checks, blood draws, side-effect assessment, diet assessment, and general monitoring.

A significant drop in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure occurred after one week of treatment and persisted throughout the study. Compared to the control, the hydrolyzed whey protein isolate reduced systolic blood pressure by 11 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure by 7 mm Hg. Treatment-related side effects, including hepatic and renal function, did not differ by group. Based on these findings, the hydrolyzed whey protein isolate appeared to reduce both systolic and diastolic blood pressure in untreated borderline hypertensives.

Individual whey proteins such as beta-lactoglobulin and alpha-lactalbumin also show additional functionalities and benefits:

• Beta-lactoglobulin binds and stabilizes fat-soluble vitamins such as A and D, making it a source for protein fortification in lowfat nutraceutical beverages with added fat-soluble vitamins.

• Alpha-lactalbumin is used in infant formula to make it more similar to human milk. It has been demonstrated to have immune-enhancing activities and is useful in sports nutrition products because of its content of branched-chain amino acids. It also enhances calcium absorption. It may also function as a potential anti-cancer agent with respect to its ability to induce apoptosis in tumor cells while not affecting healthy cells (Svensson et al., 1999). This effect was traced to high-molecular-weight oligomers of alpha-lactalbumin. Oligomerization appeared to conserve alpha-lactalbumin in a state with molten globule–like properties under physiological conditions, suggesting differences in biological properties between folding variants of alpha-lactalbumin.

• Immunoglobulins contribute to the immune response, providing protection against foodborne illnesses.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

• Lactoferrin is an iron-binding whey protein. It is often used in infant formulas fortified with iron to improve oxidative stability. It also protects against pathogenic bacteria and viruses, enhances immunity, and stimulates growth of beneficial intestinal bacteria.

• Glycomacropeptide (GMP) is a casein-derived protein found in cheese whey that stimulates cholecystokinin, the hormone that regulates food intake, helps reduce dental caries, and is beneficial for phenylketonuria (PKU). A new protein isolation process developed by researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, with funding from America’s dairy farmers and sponsored by Dairy Management Inc. (DMI), can help children with PKU obtain the protein their bodies require. Children with PKU can’t metabolize the amino acid phenylalanine, so foods high in protein are often eliminated from their diet.

According to information from DMI, GMP is one of the only known phenylalanine-free natural proteins. It is released when the enzyme chymosin breaks peptide bonds in casein, the major milk protein, during cheese making. While cheese curds are forming in the vat, the peptide fragment GMP separates into the whey, where it can constitute up to 20% of the whey protein. Ion exchange separates GMP from whey at a purity greater than 90%.

“With the availability of purified GMP, we can help food manufacturers develop a better variety of products that meet the special needs of kids and adults with PKU,” said Kathy Nelson, research specialist at the University of Wisconsin’s Center for Dairy Research.

GMP offers several functional characteristics, such as good solubility, heat stability, gel-formation properties, and foaming. The Center for Dairy Research is experimenting with a broad scope of application possibilities. Initial work suggests that GMP can be formulated into baked goods, puddings, and juices.

Additional research suggests a broader market for GMP. It has appetite-suppressing properties, which might make it a good addition to diet products or supplements. It also works to fight tooth decay by preventing the adherence of bacteria on the teeth, making it a unique ingredient for toothpaste or chewing gum.

Conjugated Linoleic Acid

Numerous animal model studies have shown benefits of conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) related to carcinogenesis, atherosclerosis, onset of diabetes, and body fat mass. CLA is a fatty acid naturally present in cow’s milk. According to DMI, researchers believe that potential health properties are linked to CLA’s molecular construction. CLA has double bonds at carbon atoms 10 and 12, or 9 and 11. The cis-9, trans-11 isomer present in milk-related CLA might hold anti-cancer properties or have a positive impact on bone health.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Researchers from Ohio State University reported that diabetics who added CLA to their diets had lower body mass as well as lower blood sugar levels by the end of their 8-week study (Belury et al., 2003). They also found that higher levels of this fatty acid in the bloodstream led to lower levels of leptin, a hormone thought to regulate fat levels. Many scientists believe that high leptin levels may play a role in obesity, one of the biggest risk factors for adult-onset diabetes.

The researchers found that one particular CLA isomer, the 10–12 isomer, helped control both body weight and leptin levels. They asked 21 people with adult-onset diabetes to take either a daily supplement containing a mix of rumenic acid and the 10–12 isomer or a safflower oil supplement as a control, for 8 weeks. Rumenic acid is the predominant isomer in foods that contain CLA, while the 10–12 isomer is less abundant.

At the end of the trial, the researchers took blood samples from each participant to check CLA levels. By then, fasting blood glucose levels had decreased in 9 of the 11 people taking the CLA supplement, but only in 2 of the 10 taking safflower supplements—a 5-fold decrease in patients taking CLA compared to patients taking the safflower oil.

The researchers also studied the impact each isomer had on changes in body weight and levels of the hormone leptin. They found that the 10–12 isomer, and not rumenic acid, reduced body weight and leptin levels.

There was only a small average weight loss among patients taking CLA supplements (about 3.5 lb), although they had been asked to not change their normal caloric intake during the study. The group taking safflower supplements neither lost nor gained weight. Leptin levels decreased in the CLA group, and rose slightly in the safflower group.

“The effect of the 10–12 isomer on reducing body mass and leptin levels was key,” said Martha Belury, Associate Professor of Human Nutrition at Ohio State University and senior author of the study. She added that other researchers have shown the 10–12 isomer to be helpful in reducing body mass in animals. “The amount of CLA, how long it’s taken and the type taken all impact the fatty acid’s ability to affect obesity in humans, and therefore help manage diabetes,” she said.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Calcium

In addition to its effect on osteoporosis, calcium consumption has also been linked to lowering the risk of colorectal cancer in women (Terry et al., 2002). Researchers studied the diets of 61,463 Swedish women for an average of 11.3 years to determine whether there was an association between dietary intakes of calcium, vitamin D, and colorectal cancer risk. Using data from a food frequency questionnaire, the researchers found that high dietary calcium intake was associated with a reduced risk of colorectal cancer, particularly cancer of the distal colon. Women over the age of 55, with the highest dietary calcium intake (816–1,300 mg/day) had a 67% lower risk of developing cancer of the distal colon and a 34% lower risk of all colorectal cancers than those with the lowest dietary calcium intake (176–568 mg/day). There was no clear association between vitamin D intake and colorectal cancer risk. The authors stated that their data suggested the association might be strongest in postmenopausal women, but that further study is needed.

Calcium has also recently been linked to weight control and weight loss. A Creighton University researcher reevaluated data from previously published studies on women and bone health to determine if calcium intake plays a role in the risk of being overweight during mid-life (Heaney, 2003). The analysis found that women who consumed lower amounts of calcium gained an average of nearly a pound a year by mid-life. Conversely, women who consumed higher amounts of calcium—the amount found in about three servings of milk, cheese, or yogurt—averaged a slight weight loss. While the author cautioned against over-zealous interpretation of the results, he estimated that the incidence of overweight and obesity may be reduced by as much as 60–80% if dietary calcium intakes were shifted upward to the current recommendation of 1,000 mg/day for women ages 19–50.

A separate review of studies that included a wide age range of Caucasians and African Americans, both male and female, found that increased calcium intake may help increase weight and/or fat loss (Teegarden, 2003). This review focused on the results of clinical trials that have investigated the impact of calcium and dairy products on prevention of weight gain, weight loss, or development of the insulin resistance syndrome. The results from this analysis implied that calcium may play a substantial contributing role in reducing the incidence of obesity and prevalence of the insulin resistance syndrome. The author concluded that “calcium and dairy products should not be removed from weight loss diets, but instead may enhance the effects of the diet.”

There is a plethora of information on these and other healthful dairy-based ingredients. The dairy industry supports a tremendous amount of ongoing research. See the accompanying sidebar for some sites that offer more information and current research on these ingredients and their health benefits, applications, and functionalities.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Probiotics and Dairy

Probiotics are live microbes that have a beneficial effect on human health. In addition to effects on the gastrointestinal tract, studies also link probiotics to beneficial effects regarding the immune system, allergies, and viral infections. Probiotics such Lactobacillus acidophilus and bacteria from the genus Bifidobacterium are mostly associated with fermented dairy products such as yogurt and kefir.

The following information from usprobiotics.org, a nonprofit research and education Web site made possible by the California Dairy Research Foundation and Dairy & Food Culture Technologies, explains why dairy products provide a desirable probiotic delivery vehicle.

• Dairy foods can protect the probiotic bacteria. Traveling through the human digestive tract can be dangerous for bacteria. High acid levels in the stomach and the high bile concentrations in the small intestine can lead to the injury and death of many members of the probiotic population. Although some bacteria are more resistant than others to this stress, consumption of probiotics with food, including milk, yogurt, and other dairy products, buffers stomach acid and increases the chance that the bacteria will survive into the intestine.

• Refrigerated storage of dairy products helps promote probiotic stability. Although the lactic acid content of yogurt can be a barrier to culture stability, refrigeration and short-term storage generally promotes stability.

• Live cultures in dairy foods carry a positive image. The consuming public may have a generally negative image of bacteria in foods, but they are aware of “live, active cultures” in fermented dairy foods, and these cultures convey a positive, healthful image. Probiotic bacteria in dairy foods can be an extension of the comfortable association of cultures in dairy products, and make it easier to communicate health messages to the public.

• The healthful properties of probiotic bacteria blend with the healthful properties of milk products. A dairy product containing probiotics makes a healthy, “functional food package.” In addition to the calcium, vitamins, other minerals, and protein obtained from milk products, modern research has suggested healthful properties of fermentation-derived peptides, conjugated linoleic acid, and butyric acid found in some dairy products.

For more information on probiotics, visit www.usprobiotics.org or see pp. 67–77 in the November 1999 issue of Food Technology and pp. 67–70 of the October 2002 issue.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Sources for More Information on Recent Research and the Health Properties of Dairy Ingredients

American Dairy Products Institute (www.americandairyproducts.com)

California Dairy Research Foundation (www.cdrf.org, www.healthywhey.org, www.usprobiotics.org)

Dairy Products Technology Center, California Polytechnic State University (www.calpoly.edu/~dptc)

Dairy Management Inc. (www.doitwithdairy.com)

Dairy Research and Information Center, University of California, Davis (http://drinc.ucdavis.edu)

Dairy Research Knowledge Exchange (www.extraordinarydairy.com)

Minnesota–South Dakota Dariy Foods Research Center (www.fsci.umn.edu/dairycenter/mndak.html)

National Dairy Council (www.nationaldairycouncil.org)

Northeast Dairy Foods Research Center, Cornell University (www.foodscience.cornell.edu/dairycenter/dairycenter.html)

Southeast Dairy Foods Research Center, North Carolina State University (www.cals.ncsu.edu/food_science/sdfrc/sdfrc.html)

Western Dairy Center (www.usu.edu/westcent)

Wisconsin Center for Dairy Research, University of Wisconsin (www.cdr.wisc.edu)

by LINDA MILO OHR

Contributing Editor

Chicago, Ill.

References

Belury, M.A., Mahon, A., and Banni, S. 2003. The conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) isomer, t10c12-CLA, is inversely associated with changes in body weight and serum leptin in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Nutr. 133: 257S-260S.

Heaney, R.P. 2003. Normalizing calcium intake: Projected population effects for body weight. J. Nutr. 133: 268S-270S.

Kashket, S. and DePaola, D.P. 2002. Cheese consumption and the development and progression of dental caries. Nutr. Rev. 60(4): 97-103.

Pins, J. and Keenan, J.M. 2002. The antihypertensive effects of a hydrolyzed whey protein isolate supplement (BioZate® 1). Cardiovasc. Drugs Therapy 16(Suppl. 1): 68.

Svensson, M., Sabharwal, H., Hakansson, A., Mossberg, A.K., Lipniunas, P., Leffler, H., Svanborg, C., and Linse, S. 1999. Molecular characterization of alpha-lactalbumin folding variants that induce apoptosis in tumor cells. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 6388-6396.

Teegarden, D. 2003. Calcium intake and reduction in weight regulation. J. Nutr. 133: 249S-251S.

Terry, P., Baron, J.A., Bergkvist, L., Holmberg, L., and Wolk, A. 2002. Dietary calcium and vitamin D intake and risk of colorectal cancer: A prospective cohort study in women. Nutr. Cancer 43(1): 39-46.