Meeting Children’s Nutritional Needs

NUTRACEUTICALS & FUNCTIONAL FOODS

The numbers are all too well known. Nationwide, approximately 30% of children ages 6–19 are overweight and 15% are obese. In addition, 70–80% of obese, adolescents become obese adults. This opens up a world of health conditions later in life, such as heart disease, diabetes, and cancer.

Childhood obesity is one of the main concerns when it comes to children’s nutrition. Lack of physical activity and poor dietary habits are two overall contributing factors to the problem. Food companies have stepped up to address the growing concern with children’s nutrition by offering healthier options and providing public awareness of healthy eating habits.

For example, last year, Kraft Foods, Glenview, Ill., established initiatives to address obesity. In terms of product nutrition, the company stated that it would be determining the levels at which the portion sizes of its single-serve packages would be capped, developing nutrition guidelines for existing and new products, and improving existing products and providing alternative choices, where appropriate. Nabisco 100-calorie packs, a four-item line featuring Wheat Thins, Chips Ahoy!, Cheese Nips, and Oreo brands, for example, are portion-controlled, single-serve products formulated to have 3 g or less of fat, 0 g of trans fat, and no cholesterol. Another new product, Kool-Aid Jammers 10, is made with real fruit juice, contains 100% of the daily value of vitamin C, and contributes only 10 kcal/serving.

In October 2003, Quaker Oats, a unit of PepsiCo Beverages & Foods, Chicago, Ill., in collaboration with the American Dietetic Association, Introduced a five-step family nutrition program called Quaker Oatmeal Strive for Five. The online program teaches parents how to prevent childhood weight gain and obesity by establishing key nutrition habits at home in one month. The program was developed on the basis of a survey of nearly 1,000 ADA-member dietetic Professionals who identified acting as a nutrition role model, eating more whole-grain foods, eating breakfast daily, and understanding portion sizes as top Ways that parents can help prevent weight gain and obesity in their children.

In addition to food companies’ initiatives, a number of Web sites offer parents and children advice and guidelines on healthy eating.

Kidnetic.com, launched in 2002, is a site for kids 9–12 years old, parents, and health professionals. Games, a frequently asked question section, discussion boards, and recipes are among the many resources available on the site. It is part of an educational outreach program of the International Food Information Council Foundation developed in partnership with several professional associations, including ADA and the American Academy of Family Physicians.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Action for Healthy Kids (www.actionforhealthykids.org) is a nationwide initiative dedicated to improving the health and educational performance of children through better nutrition and physical activity in schools. Guidance and direction are provided by more than 40 national organizations and government agencies, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrition Service.

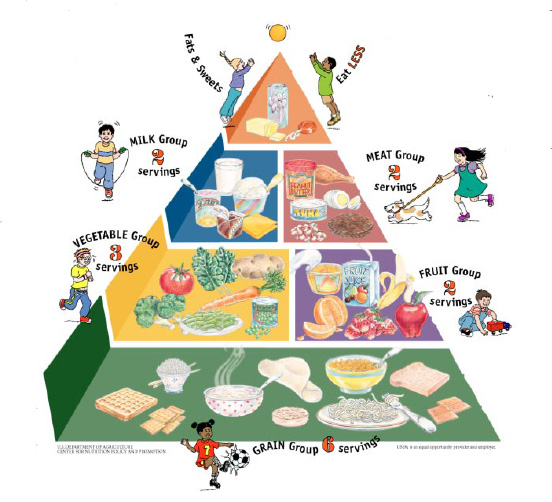

The USDA Food Guide Pyramid for Young Children (Fig. 1) offers basic nutrition guidelines for children ages 2–6 years. They include six daily servings of rains, three servings of vegetables, two servings of fruit, two servings of milk, two servings of meat, and low intake of fats and sweets.

Foods and Nutrients Children Should Be Getting More of

“Balance, variety, and moderation of many foods is the best way for children to get all of their nutrients,” said Marilyn Tanner, ADA spokesperson and clinical pediatric dietitian at St. Louis Children’s Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine. However, the simple truth is that children of all ages do not have balanced diets and are not getting essential nutrients. According to ADA, intake of several important nutrients, such as calcium and iron, is less than recommended. Here is a rundown of some food groups and nutrients that children should be getting more of:

• Fruits and Vegetables. “Children do not eat enough fruits and vegetables,” said Tanner. This is detrimental to their diets because these food groups provide fiber, vitamins A and C, B-vitamins, potassium, and complex carbohydrates for energy. Five or more servings of fruits and vegetables are recommended as part of a healthy diet. According to “State of the Plate,” a study published in October 2002 by the Produce for Better Health Foundation, 90% of teen girls and 96% of kids ages 2–12 do not eat five servings

per day.

The 5-A-Day for Better Health program gives Americans a simple, positive message: Eat five or more servings of fruits and vegetables every day for better health. The National Cancer Institute and the Produce for Better Health Foundation jointly sponsor this program. The goal of the program is to increase the consumption of fruits and vegetables in the United States to 5–9 servings every day. In addition, the program seeks to inform Americans that eating fruits and vegetables can improve their health and reduce the risk of cancer and other diseases. It also provides consumers with practical and easy ways to incorporate more fruits and vegetables into their daily eating patterns.

One way to get kids to eat more fruits and vegetables is to make them more fun and portable. According to the State of the Plate study, romaine lettuce and bag lettuce are the only vegetables that Americans are eating more of than before, increasing by an average of two annual servings per person. The bagged salads are more convenient for parents to prepare for family meals. Another example of portability is baby carrots. “Everyone loves these, and they are easy and convenient,” commented Tanner.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

• Dairy Foods. Yogurt, milk, and cheese provide calcium, potassium, phosphorus, protein, vitamins A, D, and B-12, riboflavin, and niacin. USDA recommends 2–3 servings of dairy products daily, but the majority of people only consume half of this. The 3-A-Day campaign, managed by the American Dairy Association/National Dairy Council, works to promote three servings per day. The program stresses the importance of dairy’s role in children’s health.

For example, a recent study by Goulding et al. (2004) recognized the importance of milk in children’s diets (Fig. 2). The study investigated the impact of milk consumption on children 3–13 years old. The investigators compared the fracture histories of 50 children who avoided drinking cow’s milk for extended periods of time to a group of 1,000 children from the same city, Dunedin, New Zealand.

“Children who regularly avoided milk had lower bone mineral density and weighed more, two factors that increase fracture risk,” said lead researcher Ailsa Goulding of the University of Otago, New Zealand. Nearly one in three of the young milk-avoiders had broken a bone before they were eight years old, frequently from slight trauma such as a minor trip or fall. “Forearm fractures were especially common,” said the researchers, concluding that “young children avoiding milk are prone to fracture.”

Dairy companies have made innovative strides to increase dairy consumption among children. Flavored milks, carbonated milk beverages, and flavored and colored cheese are among the newest dairy products that make dairy fun for kids. For example, Raging Cow™, from Dr Pepper/Seven Up Inc., Plano, Tex., is a five-flavor line of single-serve milk drinks. Chocolate Insanity, Pina Colada Chaos, Chocolate Caramel Craze, Berry Mixed Up, and Jamocha Frenzy are the five flavors that make milk more exciting. The company’s Web site states, “Boring milk needed a kick in the shorts, and with Raging Cow, that’s just what boring milk got.”

• Calcium. Because of insufficient dairy consumption, children’s diets are lacking in calcium. “Children under 10 need about 900 mg of calcium,” said Tanner. “Once they get to the age of 10, they need 1,300 mg of calcium per day.”

Information from the 3-A-Day program states that about 30% of kids ages 1–5 do not get the recommended amount of calcium in their diets; 70% of teenage girls and 60% of teenage boys (ages 6–11) do not meet current calcium recommendations; and nearly 90% of teenage girls and 70% of teenage boys (ages 12–19) do not meet daily calcium recommendations.

Not only is lack of calcium detrimental to children’s bone and teeth health, but also recent studies have shown that calcium may play a role in children’s weight. Research presented at the Experimental Biology Meeting in April 2003 (FASEB, 2003) suggested that girls who consume more calcium tend to weigh less and have lower body fat than those with low calcium consumption. Researchers at the University of Hawaii at Manoa and Kaiser Permanente Clinical Research Center in Honolulu studied 321 white, Asian, and mixed-ethnicity girls ages 9–14. They found that girls who consumed more calcium on average weighed less than similar girls who consumed less calcium. An increase of one serving of dairy—a cup of milk or a thumb-sized piece of cheese, about 300 mg of calcium—was associated with a 0.9 mm lower skin fold (about half an inch) and 1.9 lb lower weight.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Rachel Novotny, Professor in the Dept. of Human Nutrition, Food, and Animal Sciences at the University of Hawaii, explained that as calcium intake increases, the body increases its ability to break down fat and decreases fat synthesis.

Another study (Skinner et al., 2003) found that higher intake of dietary calcium was associated with lower body fat in young children. The study looked at 52 children ages 2–8 and their mothers. Results showed that dietary calcium and polyunsaturated fat intake were associated with a lower percentage of body fat. Milk and other dairy products were the main sources of dietary calcium in the with milk alone accounting for 50% of the total calcium intake.

• Vitamin D. This vitamin also is essential for bone health because it helps the body absorb calcium. Vitamin D deficiency largely is to blame for a rise of bone-deforming rickets in recent years among U.S. infants and toddlers, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Research at the University of Maine showed that during the winter, Maine girls are not getting enough vitamin D (Anonymous, 2004). Insufficient levels of vitamin D were detected in nearly half of 24 Bangor-area girls during a three-year study funded by the Maine Dairy and Nutrition Council. The findings worried Susan Sullivan, Assistant Professor of Human Nutrition at the university, because a history of persistent deficiencies of vitamin D could set the stage for osteoporosis later in life.

Vitamin D deficiency is most common in post-menopausal women and older Americans. However, Sullivan said, vitamin D intake is critical for children because they add calcium to their bones at a fast pace, maintain those levels into adulthood, then start to lose calcium as they grow elderly.

• Iron. “Iron is a part of blood’s hemoglobin, which carries oxygen to the cells,” Tanner said. “The oxygen helps cells produce energy, without which the body can become fatigued. Iron needs go up during the teen years.”

Infants need 6–10 mg of iron each day, and children need 10–15 mg. After age 10, children should be getting 15 mg of iron each day. Iron deficiency can be a problem, particularly for girls who experience very heavy periods. In fact, many teenage girls are at risk for iron deficiency because their diets may not contain enough iron to offset the blood loss. Also, teens can lose significant amounts of iron through sweating during intense exercise.

Iron deficiency can lead to fatigue, irritability, headaches, lack of energy, and tingling in the hands and feet. Significant iron deficiency can lead to iron-deficiency anemia.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

• Fiber. Because children are not consuming five daily servings of fruits and vegetables, their fiber intakes are low as well. To determine how many grams of fiber a child should be consuming each day, it is recommended to add 5 to a child’s age in years, said Tanner.

Fiber, especially in cereals, has been linked to the prevention of childhood obesity. A study by Albertson et al. (2003) showed that children who frequently consume cereal are less likely to be overweight. Cereal eaters were found to have a lower body mass index (BMI) and a higher nutrient intake than infrequent or non-cereal

The study, which included 603 children ages 4–12 years, examined the relationship between cereal consumption habits and BMI of school-aged children. The investigators concluded that children who consumed eight or more servings of cereal within a period of two weeks had significantly lower BMIs compared to the children who consumed fewer servings during that same time. Statistically, nearly 80% of the children who frequently consumed cereal boasted an appropriate body weight for their age and gender.

“For an average 10-year-old boy, the decision to eat cereal or not can equate to about a 12-pound difference,” said G. Harvey Anderson, Professor of Nutrition at the University of Toronto and coauthor of the study. The authors also found that cereal consumption benefited the children in the study who were at risk of being overweight. Children of this age group who ate cereal lowered their risk to 21.3%.

Another study (Quaker Oats, 2003) showed that the risk of obesity is lower for children who eat oatmeal eaters regularly compared to those who do not.The percentage of children 2–18 years old who are overweight or at risk of becoming overweight is almost 50% lower in oatmeal-eaters than in children who do not consume the fiber, according to the study, which was funded by Quaker Oats.

In addition, the study found that children who eat oatmeal are about twice as likely to meet fiber intake recommendations— fiber intakes were 17% higher than for those who do not eat oatmeal.

The findings of the study were presented by researchers from Columbia University and Quaker Oats at Experimental Biology 2003.

“This study found that children and teens who consumed higher intakes of dietary fiber had lower BMI levels or less body fat,” said Christine Williams, Professor of Clinical Pediatrics and Director of the Children’s Cardiovascular Health Center at Columbia University. “Our data further suggests children who have diets rich in high-fiber foods, such as oatmeal, as early as age two could help them prevent obesity throughout their lives.”

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Suggestions for Food Manufacturers

When it comes to formulating food for children, Tanner stressed the importance of portion sizes, in addition to important nutrients, in her suggestions for food manufacturers:

• Reduce portion size. “Sell items in smaller packages. For example, lose the “grab bag” and go back to the 25-¢ ½-oz bag,” she said. “Also consider smaller beverage containers.”

• Replace candy with fruit. “A prepackaged lunch does not need candy to sell,” she said. “Replace the goop with fruit. There are healthy options—the challenge is to keep them preserved so they are tasty and the fruit is fresh.”

• Add vegetables. “Help make veggies cool. They have a great taste and are good for you, but for some reason the “not so cool” connection is there. Advertising speaks volumes!

• Provide lower-fat, yet tasty options. “The bottom line is that kids will not eat anything if it does not taste good.”

Infant Nutrition

Newborns and infants have different nutritional requirements than children. If not breastfed, infants’ main source of food is formula. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), arachidonic acid (ARA), probiotics, and fiber, show promise in benefiting infant health. DHA and ARA are currently used in infant formulas in the U.S., probiotics enhance some formulas in Europe and Japan, and prebiotic fibers are used in some European formulas as well.

• DHA and ARA. These two fatty acids are used in infant formulas to improve the visual and brain development of infants. Researchers at the Retina Foundation of the south west in Dallas, Tex. (Hoffman et al., 2003), showed that infant formula non supplemented with DHA and ARA significantly improved the visual development of infants compared to non-supplemented formula. They studied babies who were breastfed from birth to 4–6 months of age and then randomly weaned. The babies fed the supplemented formula had improved visual acuity at one year of age, compared to the babies fed the non-supplemented formula after weaning.

“This study demonstrates the continued need for DHA and ARA in the infant diet beyond four months of age to optimize visual development during the first year of life,” said lead researcher Dennis R. Hoffman.

• Probiotics. Research has shown that probiotics in infant formula may boost the immune system. Scientists at the Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition Unit of Ben-gurion University in Israel used a double-blind placebo-controlled trial with full term healthy infants between 4–10 months of age (Asli et al., 2003). They randomly received formulas supplemented with either Bifidobacterium lactis or Lactobacillus reuteri, or the same diet with no probiotics for 12 weeks. Infants fed a probiotic supplemented formula exhibited fewer febrile episodes and fewer gastrointestinal illnesses. They noted that this effect was more prominent in the L.

• Fiber. Research at the University of Illinois indicated that adding fiber to milk formula may be beneficial on bowel health of infants (Correa-Matos et al., 2003). The study showed that piglets that consumed formula with moderate levels of fermentable fiber tolerated an induced infection by Salmonella typhimurium much better than those fed a plain control formula or one with a nonfermentable fiber.

According to the study, diarrhea is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in infants. The addition of fiber to infant formulas reduces recovery time following pathogenic infection in infants older than six months, but effects on neonates are unknown. The researchers concluded that because fermentable fiber enhanced intestinal function and reduced the severity of symptoms associated with S. typhimurium infection, it may be a cost-effective way in which to reduce the severity of pathogenic infection–associated symptoms in infants.

by LINDA MILO OHR

Contributing Editor, Chicago, Ill.

[email protected]

References

Albertson, A.M., Anderson, G.H., Crockett, S.J., and Goebel, M.T. 2003. Ready-to-eat cereal consumption: Its relationship with BMI and nutrient intake of children aged 4 to 12 years. J. Am. Dietetic Assn. 103: 1613-1619.

Anonymous, 2004. Umaine study: Teenage girls lacking in vitamin D. Univ. of Maine News press release, Jan.29. www.umaine.edu/news/020204/GirlsVitaminD.htm.

Asli, G., Alsheikh, A., and Weizman, Z. 2003. Infant formula supplemented with probiotics reduces gastrointestinal infections’ rate in day care infants. Presented at Ann. Mtg., Am. Pediatric Soc., May. www.reuteri.com/eng/sidor/studies/scientific_posters/stage2.pdf.

Correa-Matos, N.J., Donovan, S.M., Isaacson, R.E., Gaskins, H.R., White, B.A., and Tappenden, K.A. 2003. Fermentable fiber reduces recovery time and improves intestinal function in piglets following Salmonella typhimurium infection. J. Nutr. 133: 1845-1852.

FASEB 2003. Adolescent girls who consume more calcium weigh less. Press release. Fed. of Am. Socs. for Exp. Biol., www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2003-04/foasagw033003.php.

Goulding, A., Rockell, J.E.P., Black, R.E., Grant, A.M., Jones, I.E., and Williams, S.M. 2004. Children who avoid drinking cow’s milk are at increased risk for prepubertal bone fractures. J. Am. Dietetic Assn. 104: 250-253.

Hoffman, D.R., Birch, E.E., Castaneda, Y.S., Fawcett, S.L., Wheaton, D.H., Birch, D.G., and Uauy, R. 2003. Visual function in breast-fed term infants weaned to formula with or without long-chain polyunsaturates at 4 to 6 months: A randomized clinical trial. J. Pediatrics. 142: 669-677.

Quaker Oats. 2003. Study reveals oatmeal can play role in preventing childhood obesity. Press release, www.quakeroats.com/qfb_News/PressRelease.cfm?ID=201.

Skinner, J.D., Bounds, W., Carruth, B.R., and Ziegler, P.2003. Longitudinal calcium intake is negatively related to children’s body fat indexes. J. Am. Dietetic Assn. 103:1626-1631.