Solving the Obesity Conundrum

World-renowned experts participating in IFT’s third Research Summit identify key research areas for solving the problem of obesity—arguably the most pressing public health problem in this country.

The Institute of Food Technologists convened its third Research Summit on February 15–17, 2004, in New Orleans, La., to identify actions that will advance understanding of biological and physiological mechanisms affecting appetite, satiety, long-term eating behavior, energy balance vs imbalance, and food-related solutions to the obesity epidemic.

Summit organizer Eileen T. Kennedy, Adjunct Professor, Columbia University and recently named Dean of the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University, opened the Summit by asking three major questions: (1) Globally, why do we have positive energy balance that is driving the overweight/obesity epidemic? (2) Why are the biological mechanisms that have guarded against overconsumption for centuries apparently failing? and (3) What is the role of food and drink in modulating the energy imbalance? “The big issue,” she said, “is to find ways to incorporate efficacious changes into nearly transparent, sustainable actions within our everyday lives.”

World-renowned experts in food science, food technology, nutrition, and public health then heard thought-provoking keynote addresses and additional commentary from invited discussants, deliberated about the state of the obesity conundrum, and reached consensus on a number of key areas for research.

This article summarizes the keynote addresses and the commentaries from invited discussants. The PowerPoint visuals accompanying the speakers’ presentations, the list of participants, and the list of program committee members are available online at www.ift.org/cms/?PID=1000374.

Causes and Control

Two keynote addresses were presented, followed by commentary by a discussant:

Claude Bouchard, Executive Director, Pennington Biomedical Research Center, in his keynote address, “The Worldwide Epidemic of Overweight and Obesity-Environmental Causes and Control,” said that during the recent three-to-four decades, the prevalence of overweight and obesity has increased throughout the world. The increase in overweight and obesity is particularly notable in the high body mass index (BMI ≥40) classification. Approximately 1.1 billion adults throughout the world are overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 25), and almost 25 million children and adolescents in the United States are overweight. Thus, overweight and obesity have become arguably the most pressing public health problem in this country, Bouchard said.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

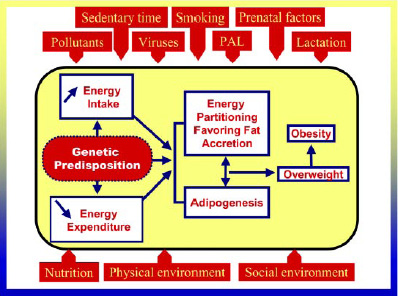

He concluded that there is not one unique reason for this obesity epidemic. However, there are many hypotheses that have been invoked to account for the positive energy balance that drives this epidemic and the failure of biological mechanisms to guard people against over-consumption. He addressed several hypotheses for the epidemic including behavioral, physical environment, and biological approaches.

Behavioral hypotheses include intake of high-calorie foods, high-fat diets, high sugar intake, low calcium intake, low protein intake, and a large amount of time spent in sedentary activities. Physical environment hypotheses relate to features of the urban environment and the potential role of environmental pollutants (e.g., organochlorines). Biological hypotheses include, among others, infant birth weight, maternal and post-natal nutrition, rise in use of high-fructose corn syrup in food formulation, low resting metabolic rates, high respiratory quotients (and low lipid oxidation rates), low leptin levels, viral infection, and genetics.

Despite the biological determinants of the predisposition for obesity, the rapid weight gain of the population can clearly not be explained by changes in the genome, Bouchard said. Rapid weight gain is most likely the result of our changing, “obesogenic” environment that encourages consumption and discourages energy expenditure-behaviors that are poorly compatible with our preagricultural hunter-gatherer genes. In this regard, attention has focused on the “thrifty genotype” hypothesis. Equally important, however, are the “gluttonous” and “slothful” genotypes as potential explanations for a biological predisposition to obesity, he said.

Noting the substantial increase in the n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid composition of the breast milk of American women during the past 50 years, Bouchard said that this phenomenon is sufficiently intriguing to warrant more research to determine whether this sets the stage for an enhanced predisposition to obesity. As for potential food-related solutions to the obesity epidemic, he said that foods could be designed to be less calorically dense and more highly satiating. He added that food manufacturers could also decrease their reliance on high-fructose corn syrup if the latter continues to be supported by the ongoing research.

Ricardo Uauy, Professor at INTA University of Chile and LSHTM University of London, in his keynote address, “The Behavioral Influences on What We Eat,” discussed a number of factors that influence eating habits: genes and their interaction with the environment, the interaction of appetite influencing neural and hormonal signals, social and individual behavior determinants, food cost, income, advertising, and marketing.

He presented data supporting several pertinent observations: (1) education is protective against obesity; (2) insulin and leptin are “center stage” in regulating weight; (3) because the brain is very dependent on sugar, our ancestral taste preference for sweets served to secure survival during evolution; (4) as the energy density of foods rises, energy consumption covertly increases; and (5) reducing the glycemic load lowers insulin levels, and helps lose body weight and fat mass. “I think we know what to do—to restore energy balance in our lives,” he said.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Some of the suggested strategies for reducing intake of energy dense foods are taxes, levies, limits on advertising, and outright bans. Control of obesity, Uauy said, will include environmental changes that make healthy food choices easy and favor active lives, in conjunction with targeting the genes that regulate food intake and activity level. He pointed to the identified need for studies on diet structure and food costs, on which to base responsible nutrition interventions and fiscal food policy. More specifically, he suggested focus on the economics of food choice, optimization of the farmer to consumer food chain, reallocation of subsidies to agricultural and industrial food production, changing trade regulations to favor consumption of healthy foods, promoting healthy choices within government programs, changing relative food pricing, facilitating healthy food selection and purchases, and providing point-of-sale nutrition information that is free of commercial interests.

To be effective, Uauy said, the entire spectrum of factors—basic causes, underlying factors, and nutrition related susceptibilities—must be considered.

Van Hubbard, Director, Div. of Nutrition, National Institutes of Health, in his commentary reported that obesity related complications—Type 2 diabetes, gallbladder disease, coronary heart disease, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, and osteoarthritis—are increasing in prevalence in men and women. Because these adverse health effects are part of a continuum, time-limited treatments are rarely effective, he said. Lifelong modification of behaviors, with prevention of weight gain in those who are not currently overweight, will be needed to solve the obesity epidemic.

Multiple sectors of the community impact effectiveness of obesity prevention and intervention efforts, he said. Given the finite limit of human and financial resources, interactions across government agencies and other organizations are imperative to enhance investments. To solve the epidemic, Hubbard said partnering among individual, community, and national strategies to accomplish the needed changes in behaviors and social norms must be emphasized.

The food industry, he added, can contribute to the solution by going beyond their own products, to provide public service. For example, manufacturers can implement innovative programs within their own workplaces and encourage other businesses to support opportunities for lifestyle change. Additionally, the industry can assist with appropriate translation of research findings and share their marketing expertise to enhance public awareness that all approaches to obesity do not work for all people.

Biological Mechanisms

The second session featured one presentation and three commentaries:

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Stephen C. Woods, Director of Obesity Research, Dept. of Psychiatry, University of Cincinnati, in his presentation, “Obesity Conundrum One: Is There Evidence That a Food Solution Can Impact Overweight Through Biological Mechanisms for Appetite, Satiety, and Energy Balance?” described the complex biological system controlling energy homeostasis and the current evidence for purported mechanisms and proposed models for control of food intake. The system relies on numerous satiety and adiposity signals in three realms—(1) visual, olfactory and taste sensations, (2) gastric and duodenal signals, and (3) ileal signals.

Undeniably, he said, the signals that control when meals occur are distinct from those that control when meals end. Most evidence related to meal initiation suggests that under normal circumstances, meal initiation is based on learned associations, convenience, or social settings. Some evidence, however, suggests that a meal-stimulating peptide (ghrelin) exists. Evidence for meal cessation strongly indicates that meal size is controlled by pre-absorptive gastrointestinal signals. The putative satiety signals most studied are cholecystokinin (CCK), bombesin peptides, apolipoprotein AIV, peptide YY (3-36), glucagon-like peptide 1, enterostatin, amylin, glucagon, and somatostatin. Most of these signals are secreted in the brain as well as in the gastrointestinal tract. Woods noted a fundamental observation-regardless of the amount of satiety factor present, a meal can only be reduced in size; meal size cannot be reduced to zero.

The potential use of foods to trigger satiety signals, such as CCK, and consequently reduce meal size has been extensively investigated. Small, statistically significant effects have been observed for soybean trypsin inhibitor, potato proteinase inhibitor, phenylalanine, and others (e.g., calcium in milk). The viability of such a strategy, however, is not clear, because when CCK is used to reduce the size of every meal, the number of meals increases, and when given alone it has no net effect on food intake or body weight. Determining whether any foods or food additives could be developed that would stimulate the ileum early in a meal would be useful, Woods said.

He added that there is considerable interest, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry, in the adiposity signals insulin and leptin because they exhibit very powerful effects on food intake and energy expenditure, and hence body weight and fat. Increased insulin or leptin signal activity in the brain, which is controlled by a very complex system in the hypothalamus, enhances satiety signals, thereby decreasing food intake and increasing energy expenditure.

Henry Koopmans, Professor, Dept. of Physiology and Biophysics, University of Calgary, commented on whether there are nutrients and hormones that alter daily food intake, body weight, and obesity. He presented results of investigations that are the basis for his thoughts on this subject. The key experiment involved a pair of parabiotic rats in which one rat loses food into the intestines and bloodstream of its partner. Observations in this model support the existence of satiety signals that are located not in the mouth or stomach but in the intestine and beyond.

Additional studies tested the hypothesis that nutrients in the bloodstream control daily food intake; i.e., that endogenous gut signals—nerves or hormones—are not involved. In the test, glucose, amino acids, and lipids were infused intravenously, by-passing the gut and supplementing the rats’ own absorbed nutrients. In this experiment, rats adjusted for about 75% of infused calories. Thus, Koopmans said, the presence of nutrients in the blood and body provide the major signals that alter food intake; endogenous gut signals may provide about 25% of the satiety signal.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

To determine where nutrients are sensed, additional infusion experiments were done, with nutrients infused into either the carotid artery or the portal vein to test the involvement of the brain and liver, respectively. These studies indicated that despite the existence of glucose receptors in both of these organs, neither organ senses plasma glucose or amino acid levels and uses the information to regulate food intake in this acute situation. The potential involvement of other organs, such as muscle and fat, which metabolize nutrients, merits future investigation, Koopmans said.

Additional studies he described addressed the role in energy balance of insulin, the main hormone that causes nutrients to move from the bloodstream into tissues. Insulin increased food intake when infused into diabetic rats, even though the rats’ blood glucose levels were high. Insulin levels in blood flowing through the brain did not have an effect; thus, the brain is apparently not involved in sensing insulin in a way that controls daily food intake. When nutrients are infused into the bloodstream, food intake is reduced; however, when insulin is released, nutrients move out of the blood and food consumption increases.

Judith S. Stern, Professor of Nutrition & Internal Medicine, University of California, Davis, focused her comments on research priorities. She believes that there likely is a food solution to obesity, albeit a complicated one. Development of public policy without sufficient science is a problem, she said.

Areas in need of research include identification of short-and long-term factors involved in meal initiation and cessation; development of measurement tools for accurate intake assessment; identification of individual markers for obesity; and determination of the impact of food ingredients and packaging on consumer behavior. Additionally, research is needed to determine the impact on satiety of liquids vs solid foods; role in food intake of portion, serving sizes, and advertising on food intake; the role of age in obesity risk; and the roles in weight control of workplace and school environments (e.g., activity level, day length, and daily nutrition).

Stern also said that the Food Guide Pyramid needs to be redesigned and that food assistance programs and the Food and Drug Administration’s pharmaceutical approval policies merit attention. The obesity-related research budgets in some organizations are insufficient, she commented. The government and Medicare/Medicaid programs must view obesity as a disease warranting high priority and conduct programmatic activities accordingly. “In the absence of quantitative research,” she said, “consumer perception prevails.”

Long-Term Eating Behavior

The third session featured one speaker and two discussants:

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Adam Drewnowski, Director, Nutrition Science Program, University of Washington, in his presentation, “Obesity Conundrum Two: Can a Food Solution Influence Long-Term Eating Behavior?” addressed several questions pertinent to obesity and the economics of food choice. While the traditional, academic view of food selection holds that the brain controls behavior and that dietary choices can be modified by learning, experience, or the food environment, consumers approach food choices in a radically different manner. Food choices are influenced by taste, cost, energy density, and convenience, and to a lesser extent by health and variety of foods. Instead of physiology influencing food choices, economically-driven eating habits may, in the long term, affect physiology and the neural systems of reward. In other words, the obesity epidemic may be causally driven by the high palatability and very low cost of energy dense foods.

It is no secret that the U.S. public does not follow the Food Guide Pyramid. The consumption of cereals, added sugars, and added fats has increased sharply during the past two decades. As is well known, the consumption of corn sweeteners has overtaken that of cane and beet sugars. However, replacing refined grains, sugars, and fats with vegetables and fruit may come up against the barrier of food costs. At this time, three fruits—oranges, apples, and bananas—account for 50% of all fruit servings. Iceberg lettuce, frozen potatoes, and potato chips account for 33% of vegetable servings. Diets composed of lean meats, fish, fresh vegetables and fruit are likely to cost more.

Drewnowski argued strongly that the key factors that drive eating behavior are economic. Addressing the economics of added sugars and fats, he pointed out that almost 40% of energy in the U.S. diet is provided by added sugars and fats, which are far cheaper, he demonstrated, than natural sugars and fats. Retail price increases between 1985–2000 were higher for fruits and vegetables than for foods containing added sugar and fat. Describing the results of a study of 837 French adults, he reported that at each level of energy intake, eating more vegetables and fruit was associated with higher diet costs. In contrast, eating more fats and sweets was associated with lower diet costs. At this time, very few studies globally (and no studies in the U.S.) have explored the relationship between dietary energy density, diet quality, and estimated diet costs.

Obesity and “unhealthy” diets are both associated with low incomes and low education. Asking low-income consumers to adopt a costly diet of lean meats and fresh produce is “blatant economic elitism,” he said. Asking whether there could be a link between dietary energy density and obesity that is mediated by low food costs, he said that more studies are needed on diet quality and cost relationships.

Richard Mattes, Professor, Dept. of Foods & Nutrition, Purdue University, in his commentary challenged the hypothesis that obesity is inversely associated with food cost and income. First, he noted that, globally, weight gain is often associated with increased economic growth. The clearest case study is that of the inhabitants of Nauru, an island in the West Pacific, where rewarding trade conditions led to high per capita income and the highest level of obesity on the planet. He also argued that obesity is often a resource allocation issue. In Brazil, China, and Russia, overweight and underweight coexist within populations and households. Gender based differences in weight status raise questions about the purported economic determinants of obesity, as well. Furthermore, the Continuing Survey of Food Intake by Individuals data indicate that people with high incomes are more likely to choose diet soda and skim milk, whereas people with low incomes tend to choose regular soda and whole milk. Thus, obesity may be related more to education and choice rather than economics.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

In challenging the hypothesis, Mattes also addressed whether energy density is a reliable predictor of a food’s dietary impact. To make the point, he contrasted beverages (e.g., carbonated soft drinks), which have low energy density, with nuts and seeds, which have high energy density. The former elicit weak dietary compensation and promote positive energy balance, whereas the latter have repeatedly been associated with strong compensation and a lack of effect on body weight. Mattes argued that there is nothing special about soft drinks or their sweeteners, rather that the fluid form of the caloric intake is the issue. Nuts may not pose a threat to energy intake, he said, because they have a very high satiety value, may elevate energy expenditure, and are inefficiently absorbed.

Hunger is multidimensional, he said, and is linked to metabolism, appetite, and cognition. To address the problem, greater emphasis is needed on whole foods/diets, total calories, lifestyles, and small but substantial modifications.

Sachiko St. Jeor, Professor of Nutrition, University of Nevada School of Medicine, in her commentary addressed the food industry’s role in solutions to obesity. The conundrum, as she presented it, reflects energy-dense foods, highly palatable/desirable foods, accessible/low-cost foods, larger portion sizes, problematic eating patterns, “toxic” food environment, and “susceptible” confused consumers.

She built a case for a new paradigm. Reflecting on the dietary trends of 2004 and “acceptable” vs current macronutrient intake ranges, she reported that weight loss is independent of diet composition (total kcal) but that weight maintenance is influenced by diet composition (macronutrients/low fat). The energy density/caloric concept needs to be separated from the nutrient quality of the diet, she said. Small changes in intake and activity can make a difference over time, she showed. The new paradigm would be composed of long term strategies for weight maintenance (±5.0 lb weight fluctuation or between any two given points in time) vs weight loss; prevention of weight gain vs weight regain; prevention of obesity and/or exacerbation of the disease state; a decrease or delay of obesity associated morbidity and mortality; improvement of health profiles/reduced risk; smaller, simpler interventions; and incremental additive steps.

St. Jeor suggested that the food solution should comprise individualized total diet approaches; a defined “basic” diet for good health; guidance for healthier choices and discretionary intake; emphasis on energy balance; a cooperative food environment; and strong partnerships combating fads and misinformation and initiating research.

Role of the Media

Sylvia Rowe, President and CEO of the International Food Information Council, in her presentation, “Role of the Media in Influencing Healthy Lifestyles,” reported that consumers are confused. The confusion stems from multiple messages from multiple sources, public skepticism about expert opinions, public misunderstanding of reports on scientific findings and results, increased media coverage unaccompanied by recommendations for physical activity and nutrition, corporate marketing strategies and health claims, and competing real-life and lifestyle demands.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

She presented results of IFIC’s “Food for Thought V Research,” commissioned by the IFIC Foundation, which is a biannual quantitative and qualitative content analysis of diet, nutrition, and food safety reporting. Since the initiation of the research in 1995, obesity and functional foods have moved into the top five topics of diet, nutrition, and food safety reporting; obesity coverage ranked highest in 2003.

Among the key 2003 findings were that obesity is currently the lens through which all issues are viewed. Factors linked in the news coverage to weight gain included eating too much, too little physical activity, failure to eat balanced meals, eating too much carbohydrates and fat, and alcohol intake. Factors linked to obesity included eating too much, too little activity, failure to eat nutritious meals, genetic predisposition, stress, boredom, “food addictions,” anger, too little calcium, and “sweet tooth.” Responsibility for obesity was attributed to fast-food companies, food producers/marketers, parents/families, individuals, and government.

Numerous suggested causes of obesity appeared in the coverage, including parental influence, food availability and low cost, soft drinks, low calcium intake, dietary carbohydrates, large portion sizes, snacks, lack of physical education in schools, personal safety, community design, computer games, television watching, automobile culture, latch-key kids, genetics, aging, depression, stress, low incomes, high incomes, low self-esteem, and a virus. The “Food for Thought V Research” was conducted by the Center for Media and Public Affairs in Washington, D.C.

Research Recommendations

Summit participants recognized the Strategic Plan for NIH Obesity Research as a comprehensive document and identified a plethora of areas warranting investigation. The potential value of some research topics was reinforced by being mentioned more than once. For example, several participants noted the value of identifying what can be learned from the non-obese, e.g., factors that contribute to maintenance of healthy habits.

A number of study areas relating to physiology were mentioned: physiological effects of dieting and weight loss; role of muscle tissue and fat in the control of daily food intake, energy expenditure, and body weight; location of the insulin (which causes increases in food intake when it’s decreased in the brain and elevated in the blood) transducer/signal; and foods or ingredients that stimulate the ileum.

As for research protocol, several participants mentioned the importance of conducting long-term as well as short-term research in a number of study areas. Research approaches need to be individualistic as well as population based.

Additional information gaps and promising research topics mentioned were genetic-based tools, e.g., genomics, nutrigenomics, metabolomics, and proteomics; applicability of smoking-cessation programs as a model for weight control, from the perspective of food as an addictive substance; and role of the postharvest food sector, including impact of commodity subsidies.

Subsequently, the participants reached consensus on a number of areas that will advance capabilities for dealing with the obesity epidemic. The outcomes of research in these areas, they noted, would be enhanced with evidence-based approaches using human subjects.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

• Prevention.This is an essential step in dealing with obesity, which participants said must be acknowledged as a disease. Some disagreement exists about the extent of lifestyle changes needed (e.g., small, meal-based or larger, long-term changes). Identification of effective interventions to enhance short and long-term weight management requires better understanding of the role in obesity of prenatal, infant, and childhood nutrition. Because childhood obesity is of such concern, participants agreed that it demands immediate attention. Parents would be well advised to participate in the development of school policies and practices to achieve needed changes (e.g., programming that increases physical activity).

Acknowledging the complexity of the obesity issue, participants believe that public–private collaboration to investigate preventive measures is necessary to successfully address the disease. Joseph Jen, Under Secretary, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, commented that the Agriculture Research, Education and Economics Service intends to contribute to the obesity prevention equation, and he mentioned a number of basic and applied research activities that the agency is actively pursuing.

• Analytical Tools. The adequacy of current measurements of food and supplement intake by various subpopulations and categories of individuals (e.g., by age, BMI) and nutrient assessment was called into question. Thus, the need to accurately assess food, nutrient, and caloric intake by different population subgroups was cited. More-precise population studies and capacity to measure small changes in various subpopulations will require technological advancements in diagnostics. Furthermore, adequate monitoring tools are needed for tracking compliance with prescribed experimental behavior interventions.Developments in personal measurement tools, enabling people to track their own nutritive and caloric intake and physical exertion, will be valuable as well.

• Predictive Biomarkers. Identification of reliable long-term behavioral and biological indicators of obesity risk is needed. Biomarkers for dietary compliance, energy intake, and energy expenditure could effectively indicate risk for obesity and associated metabolic changes. The potential for transferring technological bases of biomarkers currently used in other disciplines is worthy of investigation. Also noted is the need to pursue only those indicators that do not impact subject behavior and which can be externally validated.

• Behavior Motivations. Understanding what drives food related behavior is at the crux of the obesity issue, one participant noted. The group agreed that “real-life” investigations into motivations for food choices and the initiation and cessation of eating occasions are needed. Furthermore, knowledge of the short- and long-term impact on behavior of psychosocial, cultural, and, hence, lifestyle influences on healthy and unhealthy weight, is also needed. More specifically, the influences on behavior of food composition, properties, cost, portion size, packaging, labeling, and availability need to be determined. In addition, the impact of time allocation and time constraints on behavior and the impact of time constraints on time allocation need to be investigated. Once the drivers of food-related behavior are better understood, more-effective strategies for behavior modification can be established.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

• Communication and Education. Because individuals have personal responsibility in weight management, through diet and exercise, participants also agreed that consumer education is a key component in limiting the epidemic. While availability of nutrition information is critical, provision of such information is not education. Delivering successful educational programs requires research into effective positive and negative messages, consumer interpretation of nutrition information, and “hot buttons” for learning. Harnessing the marketing expertise within the food industry to help the public understand that all weight-control approaches do not work for everyone was suggested.

• Satiety. Participants agreed that factors having an influence on satiety and medium and long-term food intake must be identified and understood. Such food related influences on satiety may include fiber, macro- and micronutrients, phytochemicals, probiotics, peptides, flavors, and water. Furthermore, better understanding of the role in satiety of sensory characteristics of foods, e.g., texture, taste, and form (liquid vs solid), is also needed. Information on the role in satiety of cognition and any psychological effects of food components would also be helpful. Longitudinal investigations to determine whether satiety signals change with age or physiological state are needed.

Studies to determine whether food processing affects food components that may have an impact on satiety could also be useful. Ileal transposition has been shown to cause a small but reliable weight loss; participants agreed that determining the relationship between ileal peptides and satiety would be useful. Additionally, it would be important to investigate whether certain foods or food components act as antagonists of appetite-stimulating substances such as ghrelin or, conversely, stimulate key brain areas involved in energy regulation to decrease food intake and increase energy expenditure.

• Food Solutions. Identifying whether successful, sustainable weight-control interventions, however slight, can be achieved through food formulation is a priority. Determining whether specific foods or combinations of foods can be used to manage energy intake to decrease obesity was noted as a study area. Related to this, participants suggested that nutrigenomics may be applicable to determine whether different types of diets affect individuals differently. Furthermore, the group concluded that a key research question is whether food manufacturers can make minimal changes in the energy density of foods (e.g.,5% reduction in caloric value), and thereby contribute to effective weight reduction. In addition, it would be valuable to investigate the impact of certain foods on thermogenesis and energy loss. Better understanding of the influence of food packaging on food intake is also needed.

• Other Issues in Understanding Obesity. Understanding the genetic, metabolic, and psychological factors that may contribute to obesity is important. Research into the hypothesized obese genotypes is needed. The “thrifty” genotype describes the selection of genes favoring conservation of energy during periods of limited food supply. Other potential genotypes—the “gluttonous” genotype, which favors hyperphagia, and the “slothful” genotype, which favors energy conservation under caloric deprivation—appear to be more prevalent than the thrifty genotype and warrant more investigation. Additional research to identify more of the specific genes and DNA sequence variants related to obesity, the synergistic relationship between genes and the environment (as seen in the Pima Indians), and the genetic predisposition for obesity is needed.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

More studies are needed to assess whether or not all calories are equal, more specifically, to determine if there is a scientific basis for differences in food composition contributing to weight gain, excess body fat, and loss of muscle mass.

An understanding of whether there are habit-forming characteristics of certain foods or food ingredients and the scientific basis for the proposed addictive nature of certain foods needs elucidation. For example, it is known that babies respond to the sweet taste of sugar at an early age. A better understanding of how acquisition of food preferences and avoidances occur is needed.

Integration of Research Efforts

In reaching consensus on the research topics identified above, discussion evolved to the need for a clearinghouse for research outcomes as applied to solutions to the obesity epidemic. Participants identified the need to compile in one central location the results of current research and coordinate research outcomes with ongoing and future research efforts within government, industry, and academia.

Establishment of such a clearinghouse would enable better implementation of actions that can be effective at the present time and determination of which study areas warrant more attention. Participants generally agreed that IFT would be the logical home for this clearinghouse, allowing research expenditures to be better tracked and public–private research coordinated.

by Jennifer MacAulay and Rosetta Newsome

Author MacAulay ([email protected]) is Staff Scientist, Institute of Food Technologists, Office of Science, Communications, & Government Relations, 1025 Connecticut Ave., N.W., Washington, DC 20036-5422. Author Newsome ([email protected]) is Director, Dept. of Science and Communications, Office of Science, Communications, & Government Relations, Institute of Food Technologists, 525 W. Van Buren St., Chicago, IL 60607.