A Holistic Approach to Product Development

Emotive research refocuses the development process from product features to consumer-product experiences, leading to successful trial and repeat purchases.

When we consider buying foods such as chocolate, our minds are filled with emotions, yet our research methods focus on purchase intent and liking. Is it a wonder, then, that new product success rates are low in the food industry?

Hoban (1998) cites success rates as low as 2%. Less than 25% of new products launched in 2005 exceeded $7.5 million, and less than 1% exceeded $100 million in year-one sales (IRI, Inc., 2006).

The Product Development Management Association (PDMA) reports that 68% of consumer packaged goods companies use a phase-gate approach to product development. The Stage-Gate® process (Cooper, 2001) claims improved success rates through faster market responsiveness. However, an industry survey reported by Adams-Bigelow and Griffin (2005) found accelerating development cycle times reduce, not increase, the rate of new product success. As companies search for faster responsiveness and higher success rates, unresolved issues remain at the heart of the product development process. Perhaps the key to improved new product success is generating and utilizing better consumer research information.

Sensory evaluation and marketing research bring the voice of the consumer into the new product development process through a wide range of quantitative and qualitative research methods. Product liking ( i.e., “How well do you like this product?”) and purchase intent are often used to gauge hedonic affinity and purchase intention, respectively, for products as a whole, or to specific product components such as concept, package, brand, and sensory qualities. However, evidence exists that purchase intent is a poor univariate predictor of purchase probability (Kalwani and Silk, 1982; Chandon et al., 2005).

It is often unclear how liking relates to purchase behavior, especially when products provide functional, in addition to hedonic, benefits. To improve product success rates, marketers and product developers need better measures that deepen insights into how products as a whole elicit compelling, differentiated product experiences.

Emotions are the underlying motives of human behavior. Various emotive topologies have been proposed (Desmet, 2005). Overall liking, for instance, is a measure of product love (i.e., liking an appealing object). Accurate measurement of emotions other than product love may create opportunities for companies to increase new product success rates. For example, chocolate products may be equally liked, but not equally desired for their sheer decadence. A dark chocolate may elicit more pride than a white chocolate due to its perceived health benefits.

Linking brand, concept elements, package design and function, product features and usability, and expected benefits to emotions establishes a strategic framework for marketers, package designers, and food developers to holistically design and develop products. Emotive measurements have the potential to change the product development paradigm, refocusing development away from product features to product experiences, from liking drivers to emotive levers, and from optimization to harmonization.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Emotions and Emotive Levers

Behavioral psychologists have developed many theories to explain consumer behavior. For instance, contrast assimilation theory provided an early framework linking consumer expectations to behavior (Cardello et al., 1985). Now a more complex, rich theory is emerging. Attitudes, beliefs, expectations, concerns, and fulfillment of self-social identity are all being shown to elicit product emotions and behaviors (Elliott, 1998; Kempf, 1999; Phillips and Baumgartner, 2002; Desmet, 2003).

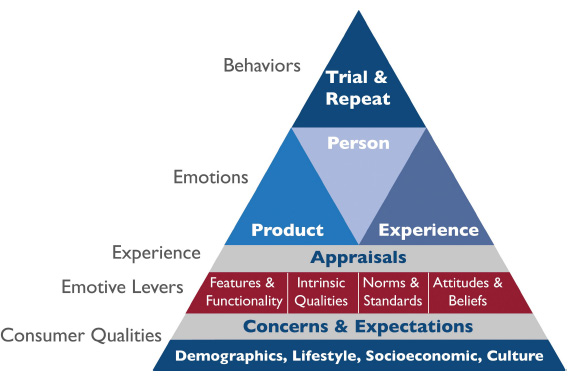

To apply this theory, a framework of “emotive levers” is required, which in turn can be used in product development to elicit specific emotions and behaviors. Figure 1 provides a framework linking concerns, expectations, and appraisals to emotions—and subsequently to behaviors.

To apply this theory, a framework of “emotive levers” is required, which in turn can be used in product development to elicit specific emotions and behaviors. Figure 1 provides a framework linking concerns, expectations, and appraisals to emotions—and subsequently to behaviors.

Concerns are the basic needs that consumers strive to fulfill—achieving basic goals, maintaining standards, and adhering to held attitudes and beliefs. Expectations are the experiences that consumers believe will result from product use; they can be characterized as functional, hedonic, and self-social identity fulfillment. Appraisals involve cognitions and/or perceptions of product qualities, features, and functionality on the basis of motive compliance against goals, authenticity in experiences, standards of identity, or novelty.

In the context of consumer packaged goods, consumers experience multiple points of appraisal. Products are appraised conceptually prior to and at point of purchase, and experientially during product preparation and consumption. These appraisals form a cascade of interrelated expectations and emotions leading to trial and repeat motivations (Figure 2).

In the context of consumer packaged goods, consumers experience multiple points of appraisal. Products are appraised conceptually prior to and at point of purchase, and experientially during product preparation and consumption. These appraisals form a cascade of interrelated expectations and emotions leading to trial and repeat motivations (Figure 2).

Motivations for trial are driven by emotions and rational thoughts elicited during product (concept) appraisals. Motivation for repeat behavior is driven by emotions and rational thoughts elicited during product experiences (i.e., through preparation and consumption appraisals). This framework shows that emotions are dynamic in nature, enhanced or mitigated during product preparation, and/or through sensory cues that are perceived prior to consumption. Less dynamic are consumer concerns that form the basis of all appraisals against a range of various, unfulfilled needs.

Expectations and concerns affect how we appraise consumer products. Expectations are dependent on our memories and rational thought. Memories are strongest when associated with emotional experiences. We are discovering patterns where specific expectations and concerns lead to specific emotions. For example, experiencing an expected functional benefit often leads to satisfaction. Heightened hedonic expectations and experiences tend to elicit enjoyment. A novel product elicits pleasant surprise or amusement. Association of product use with someone you admire elicits pride. Thus, a product may be liked for a combination of hedonic and functional benefits, yet liking may not be the key driver of behavior. Focusing only on maximizing liking for product guidance may completely miss the mark.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Emotive Research

Much debate currently exists in the sensory and market research communities as to whether product emotions can be measured quantitatively. There is concern that rational thoughts used to consider questions and rate feelings result in biases. Yet, hedonic questions and rating scales have proven themselves valid measures of liking (i.e., product love). Why not for other emotions? Frijda et al. (1992) reported that emotional responses are multidimensional and measurable quantitatively. Furthermore, an icon set has been developed into a software product, Product Emotion Measurement tool—PrEmo, for collection of nominal (presence/absence) emotional responses (Desmet et al., 2002). The challenge may be more about leveraging research designs and methods that ensure that derived measures accurately reflect true emotions.

Emotive research requires holistic research design. In such a design, respondents must be presented with complete information about the product concept to elicit accurate expectations. Recruitment and segmentation must be based on concerns, rather than demographics or past product use. Respondents must be exposed to product experiences similar to real-use situations. Research objectives must be focused on eliciting specific emotive measures.

If emotions are measured quantitatively, appropriate rating scales, questions, and questionnaire designs must avoid psychological errors in judgment and bias. If consumer language associated with emotions is unknown, methods such as free association profiling (Stucky et al., 2005) can lead to language discoveries. The complexity of a multivariate emotive response requires new tools for seeing data relationships (Lundahl et al., 2005). If emotions are measured qualitatively, researchers must select respondents who represent segments of consumers with similar feelings and behavioral motivations. This can be achieved by using “quant-qual” methods with rapid screening on the basis of real-time quantitative response monitoring (Lundahl and Stucky, 2005).

Instant Coffee Example

Instant Coffee Example

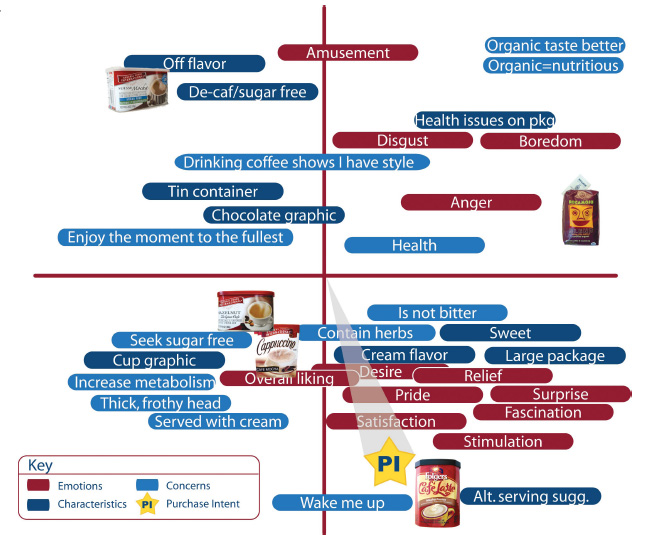

These emotive theories were applied to the specialty instant coffee category (Figure 3). As a first step, an Internet survey was conducted with respondents who described their concerns associated with instant coffees and rated five product concepts for purchase interest and expectations. These data were used to develop a recruitment tool based on purchase intent patterns, typing respondents into one of five groups for a subsequent central location study. This study was designed holistically, allowing respondents to first evaluate a product concept, then prepare and consume it, rating their feelings about each experience.

Respondents rated their feelings about product experiences (e.g., satisfaction, enjoyment, stimulating, pleasant/unpleasant surprise, disgust, amusement, and surprise), products (e.g., liking, desire), themselves (e.g., pride, relief) or the manufacturer (e.g., anger). Emotive response patterns were monitored in real-time to select respondents for one-on-one interviews. This quant-qual method allowed researchers to deepen insights and validate quantitative ratings.

Descriptive analysis was used to characterize each product on the basis of sensory perceptions, brands, claimed functionality, and package features. The causal relationships between these emotive levers (i.e., concerns and product characterizations) and emotions were identified by mapping quantitative responses with a predictive modeling method called mN-PLS (Plaehn and Lundahl, 2006).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

This holistic approach to research resulted in a comprehensive understanding of how consumers differ in response to these five product experiences. The quantitative research resulted in five segments with distinctive emotive patterns and emotive levers. Maps of the data relationships for one of these segments (“Frothy”) are displayed in Figure 4.

The selected one-on-one interviews provided researchers with an opportunity to further characterize respondent feelings, linking feelings to expectations held prior to preparation and consumption, and tracing their feelings back to underlying concerns associated with the product category. The following quote from a respondent (identified as a “Frothy” segment member) shows the ability of respondents to characterize their feelings and to describe underlying causes.

“I was surprised that the product actually frothed when I added the hot water. It was amusing to watch the froth grow over time. I didn’t expect this from an instant cappuccino. I host coffee groups in my neighborhood and would be proud to serve something like this to my girlfriends. I think they would enjoy it as much as I did.”

This holistic, quant-qual methodology enabled researchers to attain a more complete view of the consumer experience. The “Green” segment was the only group interested in purchasing the Organic Rocomojo product. The “organic” label complied with two consumer goals (achieving good taste and health) by adhering to an attitude that organic delivers better taste and health. This group also was fascinated by the package graphics/colors and surprised that an organic, roasted soybean coffee could be an instant product.

The “Diet” segment was the only group interested in purchasing the General Foods Sugar Free Decaf product. They were concerned about their weight, expressed surprise that this product tasted so good, and relief they were doing something so good for their health. The “Frothy” segment had high purchase interest for the General Foods Café Mocha Cappuccino and Folgers Café Latte products. They desired an instant coffee with a creamy mouthfeel and minimal bitter flavor. They were surprised that the instant cappuccino frothed, were fascinated to watch the froth grow, and stated that they would be proud to serve these products to family and friends.

As a result of emotive research, product developers, package engineers, and marketers all gain valuable information applicable to their respective domain expertise. This information helps project teams achieve product development harmony, developing coordinated strategies to achieve successful trial and repeat. To target the “Frothy” segment, project teams working within the holistic process would set objectives to elicit surprise, fascination, desire, and pride through product design. Coordinated development themes focus activities on using specific emotive levers to elicit these emotions. For example, marketing may develop an advertisement portraying pride and fascination while serving friends. Package designers may develop artwork to heighten desire and fascination. Product developers may formulate a creamy, slightly bitter-tasting product to maximize desire and a thick, frothy head to elicit fascination. This leads to product harmony and a more compelling product experience.

The Holistic Paradigm

If the food industry is to improve its historical low rate of new product success, companies must improve the way they take ideas to market, adopting a different product development paradigm. By measuring emotions that motivate consumers to trial and repeat behavior, holistic research methods enable researchers to focus development activities on the entire experience.

For example, early discovery of emotions and emotive levers focuses product development activities on opportunities with the highest chance for success. Holistic research methods pave the way for rapid prototyping where “protocepts” (i.e., concept and rough prototype) are developed and tested experientially to gauge emotive response behaviors. This leads to an iterative product development process of discovery, refinement, and assessment where rough protocepts are refined into viable products.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

The sensory professional plays an important role in supporting the holistic product development process. Sensory groups offer organizations unique skills, capabilities, and expertise in product testing. These skills are essential to elicit accurate emotions to product experiences. Holistic research methods require sensory groups to capture more, rather than fewer, dimensions of the consumer experience. This shifts research from the laboratory into the field where holistic research design results in consumer insights of greater strategic value.

By embracing a holistic paradigm, the food industry can break out of the mindset that liking and purchase interest are sufficient measures for bringing the voice of the consumer into the product development process. Improving the information basis to make product development decisions leads to a more consumer-centric product development process where concept, product, and package are developed in concert, achieving product harmony and eliciting strong positive emotions.

Through emotive research, a more holistic product development process increases the odds that new products will achieve success through the delivery of compelling, differentiated experiences.

by David Lundahl, Ph.D., a Professional Member of IFT, is President & CEO, InsightsNow, Inc., P.O. Box 1628, Corvallis, OR 97339 ([email protected]).

References

Adams-Bigelow, M. and Griffin, A. 2005. Product development cycle time and success: New results from PDMA’s comparative performance assessment study. Product Development and Management Assn., Mt. Laurel, N.J.

Cardello, A.V., Maller, O., Masor, B.M., Dubose, C., and Edelman, B. 1985. Role of consumer expectancies in the acceptance of novel foods. J. Food Sci. 50: 1707-1718.

Chandon, P., Morwitz, V.G., and Reinartz, W.J. 2005. Do intentions really predict behavior? Self-generated validity effects in survey research. J. Mktg. 69: 1-14.

Cooper, R. 2001. “Winning at New Products, Accelerating the Process from Idea to Launch,” 3rd ed. Perseus Publishing, Cambridge, Mass.

Desmet, P.M.A. 2003. A multilayered model of product emotions. Design J. 6(2): 4-13.

Desmet, P.M.A. 2005. Basic set of emotions. A typology of fragrance emotions. In “Fragrance Research 2005, Unlocking the Sensory Experience,” pp. 134-145. ESOMAR, Amsterdam (ISBN 9283113780).

Desmet, P.M.A., Hekkert, P., and Jacobs, J. 2002. When a car makes you smile: Development and application of an instrument to measure product emotions. Adv. Consumer Res. 27: 111-117.

Elliott, R. 1998. A model of emotional-driven choice. J. Mktg. Mgmt. 14: 95-108.

Frijda, N.H., Andrew, O., Sonnemans, J., and Clore, G.L. 1992. The complexity of intensity: Issues concerning the structure of emotional intensity. In ”Emotion, Review of Personality and Social Psychology,” Vol. 13, pp.60-89. Sage Publications, London.

Hoban, T.J. 1998. Improving the success of new product development. Food Technol. 52(1): 46-49.

IRI. 2006. 2005 New pacesetters: Leading new CPG brands. In Times&Trends, Information Resources, Inc., Chicago. www.infores.com.

Kalwani, M.U. and Silk, A.J. 1982. On the reliability and predictive validity of purchase intention measures. Mktg. Sci 1: 243-286.

Kempf, D.S. 1999. Attitude formation from product trial: Distinct roles of cognition and affect for hedonic and functional products. Psychol. Mktg. 16(1): 35-50.

Lundahl, D.S. and Stucky, G. 2005. Bridging the qualquant divide. Presented at Inst. of Food Technologists Ann. Mtg., New Orleans, July.

Lundahl, D.S., Plaehn, D., and Ingersoll, D. 2005. Driving fragrance research through predictive modeling. In “Fragrance Research 2005, Unlocking the Sensory Experience,” pp. 1-21. ESOMAR, Amsterdam.

Philips, D.M. and Baumgartner, H. 2002. The role of consumption emotions in the satisfaction response. J. Consumer Psychol. 12: 243-252.

Plaehn, D. and Lundahl, D.S. 2006. An extension of NPLS to multiple regressors. Unpublished manuscript, InsightsNow, Inc., Corvallis, Ore.

Stucky, G., Wiacek, K., and DiCasoli, R. 2005. Capturing the implicit mind: Qualitative fragrance imagery by free association. In “Fragrance Research 2005, Unlocking the Sensory Experience,” pp. 134-149. ESOMAR, Amsterdam.