Food Allergen Test Kits

LABORATORY

The prevalence of food allergies worldwide has nearly doubled during the past 20 years, doctors and scientists observe. Approximately 4% of the U.S. population is believed to be suffering from one or more food allergies, according to Wesley Burks, Chief of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C. ([email protected] With the current population estimated by the U.S. Census Bureau to be 299,682,000, that means that nearly 12 million people suffer from food allergies.

"The number of individuals affected by this disease is virtually immeasurable when family, friends, caregivers, associates, and health care providers of sufferers, along with food allergy researchers, foodservice providers of various types, and even all the players in the entire food industry from farm to fork are taken into account," Burks says.

"The number of individuals affected by this disease is virtually immeasurable when family, friends, caregivers, associates, and health care providers of sufferers, along with food allergy researchers, foodservice providers of various types, and even all the players in the entire food industry from farm to fork are taken into account," Burks says.

Eight foods or food groups are thought to account for more than 90% of all immunoglobulin E–mediated ("true") food allergies. Known as the "Big Eight," they are milk, eggs, finfish, crustacean shellfish, peanuts, soybeans, tree nuts, and wheat.

The foods most likely to cause anaphylaxis, the most severe form of allergic reaction, are peanuts, tree nuts, and shellfish.

"Almost any food has the potential to trigger an allergy," Burks emphasizes. "More than 160 other foods have been documented as causing food allergies less frequently."

The only way to avoid experiencing allergic reactions is to completely avoid the offending foods. Knowing that some consumers have food allergies can complicate commercial food production significantly. Despite stringent cleaning protocols embraced by manufacturing facilities, there are constant industry concerns about contamination with trace amounts of food allergens.

Manufacturers are responsible for following the requirements of the Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004 (FALCPA), which became effective on January 1, 2006. The bill requires food manufacturers to state clearly if a product contains any of the "Big Eight" foods/food groups.

Domestic or imported packaged foods that are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration are required to make changes to their labels that list the type of allergen—e.g., the type of tree nut (almond, walnut) or the type of crustacean shellfish (crab, shrimp)—as well as any ingredient that contains a protein from the group of eight major food allergens. The labels also must include any allergens found in flavorings, colorings, or other additives.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Use of Test Kits Increases

Food manufacturers are using commercial enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) tests more than ever to ensure the absence of undeclared allergens in food and to validate allergen control measures, says Tong-Jen Fu, an FDA research scientist at the National Center for Food Safety and Technology, Div. of Food Processing and Packaging, Summit, Ill. ([email protected]).

In fact, according to the Food Allergy Research & Resource Program (FARRP) at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, lawyers who specialize in food law consider using allergen residue test kits to be the "standard of care" in the United States.

Many of these tests are designed to allow quantitative determination of food allergens where the presence of the target protein is detected by binding with specific antibodies, Fu points out. The concentration of the antigens is then determined from a standard curve generated with reference protein standards.

"Because quantitation is achieved via measurement of antigenicity, any changes in the antigenic property of the target proteins may greatly influence assay results," she says. "For example, thermal processing can change the antigenic property."

Heat often affects the solubility and immunoreactivity of proteins, but how the thermal treatment of food affects the quantitation of allergens by ELISA test kits remains to be determined, she says.

In a recent study, Fu compared the performance of two major types of test kits, one that employs antibodies that are reactive to all protein components in allergenic foods and one that uses antibodies that are specific for a single allergenic compound or marker protein.

Both kits were used to detect egg that had been subjected to moist or dry heat. Elevated heat treatment resulted in a lower level of proteins being extracted. While the decrease in the amount of extractable protein in dry-heated samples was generally reflected in the readings observed using both test kits, the change in the amount of extractable proteins in boiled samples was not proportionately indicated by either test kit.

The test kit that was reactive to all protein components in egg underestimated the amount of residual protein in boiled samples. The kit that employed antibodies specific to a heat-stable marker protein (ovomucoid) overestimated the amount of protein remaining.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

"These results suggest that heat-induced changes in the solubility and structure of proteins need to be considered when commercial ELISA test kits are used for the quantification of allergens in thermally processed foods," Fu says.

Besides providing food manufacturers with a useful tool for testing ingredients, food allergen test kits have other uses.

"We need to be able to accurately and reliably detect food allergens from the perspective of what the consumer may purchase or eat," says Eric A.E. Garber, Lead for Food Allergen Methods at FDA’s Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, College Park, Md. ([email protected]).

"For that reason, there is a need to conduct detailed evaluations of the test kits with the ultimate goal being to have validated methods," Garber explains. "Through validation, the results obtained using a test kit are defined relative to a recognized reference material and the performance characterized statistically. If you use different brands of test kits for the same allergen with the same sample, you should obtain the same result at a defined level of confidence. That’s the goal of validation."

Ongoing Research Collaboration

To address the critical need for validated methods for the detection of food allergens in food products, research scientists from FDA, Health Canada, FARRP, the Food Products Association, and the European Commission’s Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements began in 2005 a collaboration to maximize the use of available scientific expertise and laboratories for validation trials.

"By employing the best science possible and working with the test kit manufacturers, potential problems are identified and troubleshot, and the test kits validated," Garber relates. "The collaborating researchers want to facilitate the successful validation of test kits. This provides more analytical tools for any user concerned with detecting food allergens."

For their initial project, the group tackled the validation of egg allergen detection test kits. This required three phases.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

"First, the five collaborating laboratories evaluated the performance of six different test kits with two potential reference materials," Garber says. "Based on the results obtained, a spray-dried, whole egg powder was chosen to be the reference material for this study. This material has been deposited with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) as a reference material and represents the first NIST reference material specifically designed for food allergen detection."

Currently, in the second phase, test kits are being evaluated with food samples representative of those that will be used in the multi-laboratory validation.

Finally, in the third phase, after identifying and sharing the results with the test kit manufacturers, a multi-laboratory validation will be conducted at the 95% confidence level for four matrices containing egg at three concentrations (one concentration is 0 and two other concentrations, one representing a target level and the second encompassing the calibration curve), using a minimum of 10 laboratories. The validation study will also examine the specificity/cross-reactivity of the test kits with other foods.

"In addition, FDA scientists are conducting extensive in-house evaluations of commercial test kits, including those for milk, wheat/gluten, egg, and soy," Garber mentions. "FDA scientists also examined the effects of various forms of preparation, such as baking, boiling, and freezing, that represent the products the consumer may acquire and affect the utility of the test kits. By including proper controls and foods that have undergone preparation in the evaluation and validation studies, the utility of the test kits for detecting and quantifying food allergens is understood."

An Important Tool

Overall, manufacturers have done an excellent job in designing test kits, making them an important tool in the arsenal used to determine the presence of food allergens, Garber points out.

"By utilizing sensitive, reliable methods that have been extensively evaluated and validated, when a consumer complaint is made about a food product we can accurately determine whether a food allergen was present, thereby safeguarding the consumer and avoiding erroneous conclusions regarding food products," he says.

Garber is quick to mention that there are still mysteries about test kits that need to be solved. "Our methods are focused on antigenicity and detectability. The effects of preparation on the bioavailability and allergenicity of food allergens are not fully understood."

--- PAGE BREAK ---

There are two major needs that still prevail relative to enhancing allergen test kits as a tool, says Timothy Hendra, Director of Diagnostic Sales for Neogen Corp., Lansing, Mich. ([email protected]).

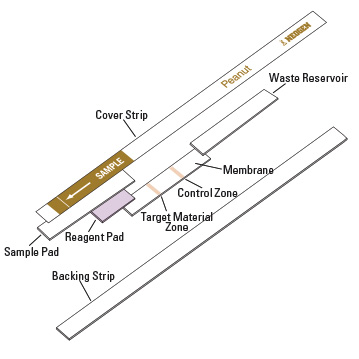

"We continue to work to make test kits easier and quicker to run. Waiting even 20–30 minutes for test results between runs impacts the efficiency of the food manufacturing process," Hendra says. "And test kits are needed for additional allergens, such as tree nuts like walnuts and pecans, processed soy, and shellfish. Neogen currently has ELISA test kits for detection of peanuts, egg, milk, almonds, gliadin, hazelnuts, and soy flour. Our goal is to have all test kits in the 5-min lateral flow format. As these improvements are made, I believe test kit use will increase dramatically."

"We continue to work to make test kits easier and quicker to run. Waiting even 20–30 minutes for test results between runs impacts the efficiency of the food manufacturing process," Hendra says. "And test kits are needed for additional allergens, such as tree nuts like walnuts and pecans, processed soy, and shellfish. Neogen currently has ELISA test kits for detection of peanuts, egg, milk, almonds, gliadin, hazelnuts, and soy flour. Our goal is to have all test kits in the 5-min lateral flow format. As these improvements are made, I believe test kit use will increase dramatically."

"The future holds promise for the food-allergic consumer, as allergen tests will become more reliable, specific, and targeted for what they should do," says Bruce Ritter, founder and President of ELISA Technologies, Inc., Gainesville, Fla. ([email protected]).

Despite his optimism, Ritter doesn’t hesitate to mention the kinks that need to be worked out of allergen testing. "One drawback right now is the lack of sufficient clinical data on thresholds for the allergens, as well as regulatory guidelines that would allow test makers to target the appropriate range of sensitivity of allergen tests. There is such a wide range of patient sensitivity to allergens. We need better clinical information and clear regulatory specifications regarding identification of specific allergenic target levels."

Another challenge is the food matrix itself. "The detection of allergens in foods is affected by the composition and processing of the food products," Ritter says. "If you have a protein responsible for an allergy in five different food products, for example, different amounts of allergenic protein will be recovered from the different foods after processing. A test kit may not see the part that has been changed. The relevance of the modified and undetected proteins in allergic reactions is still largely unknown."

No one test can do it all, Ritter says, and currently all the commercial test kits have specific targets and limits of detection.

"While the tests produce few false positives, no test can test down to zero, and all methods will produce ‘false negatives’ with samples containing allergen levels below the detection limit," Ritter elaborates. "The differences in the allergen threshold range among allergenic people make food manufacturing, testing, and regulation more difficult.

However, analytical tools are available that can target clearly relevant levels of allergens in foods that can affect allergic consumers and lead to recalls. The food industry needs appropriate guidelines and testing tools to deal with these issues so they can produce foods that consumers with allergies can trust."

Manufacturers of Food Allergen Test Kits

The following is a list of some companies that manufacture food allergen test kits that are not already mentioned in this article.

Biotrace International PLC, Bothell, Wash. (phone 425-398-7993, www.biotraceamericas.com)

r-Biopharm Inc., Marshall, Mich. (phone 877-789-3033, www.r-biopharm.com)

SafePath Laboratories LLC, Carlsbad, Calif. (phone 760-929- 7744, www.safepath.com)

Tepnel BioSystems, Stamford, Conn. (phone 802-849-2948, www.tepnel.com)

by Linda L. Leake,

Contributing Editor,

Food Safety Consultant, Wilmington, N.C.

[email protected]