Driving Growth Through Open Innovation

Open innovation strategies, career development, goal setting, and more were on the agenda when IFT members assembled for the second annual Strategic Leadership Forum.

Imagine coming into your workplace each morning and not treading a familiar path to your office or cubicle—because you don’t have one. Sound a bit unorthodox? Such a set-up may be hard to fathom for many of us, but for members of seven “Future Teams” at GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare, it’s a daily reality—and just one aspect of the company’s venture into “open innovation” to energize product development and fuel business growth.

Richard McGregor, Associate Director, Open Innovation, GSK Consumer Healthcare, offered a close-up view of the company’s paradigm shift in a session titled “Embracing Open Innovation Ideas at Work” held at IFT’s Strategic Leadership Forum March 27–29.

The Forum, which drew about 150 established and emerging IFT leaders, offered a full schedule of sessions and activities that elicited feedback on key organizational issues, encouraged networking, provided leadership training, and updated attendees on industry trends. McGregor’s session also featured presentations by Steven Goers of Kraft Foods and James Zuiches of North Carolina State University.

In late 2006, GSK Consumer Healthcare embarked on an Open Innovation campaign in an effort to jump-start product development and to help stem a pattern of declining sales growth. The company has sales of more than $6 billion annually and has a stable of powerful brands, including over-the-counter weight loss aid alli, Tums heartburn remedy, and Aquafresh toothpaste. Implementing a series of changes designed to create a more open and collaborative environment produced dramatic results. In 2007, GSK racked up sales growth of 14%.

Fusion Fuels Momentum

At GSK Consumer Healthcare, senior leadership used the process of fusion—in which multiple particles join to form a nucleus accompanied by a release of energy —as a model for change.

“We looked at creating fusion inside GSK,” McGregor said. Creating the “Future Teams,” structured around the company’s seven major global brands, was the first step. Each team is co-led by a commercial and R&D vice president. Team participants include staff members from research and development, commercial ideation, regulatory, manufacturing, and business development.

With the advent of the new approach came the introduction of the “hub” workplace environment, which brings together team members in an open space floor plan without walls, offices, cubicles, or even assigned desks. Employees utilize mobile carts to house personal/confidential work materials. Even members of the management team are housed together within a “leadership hub.”

“This sent a signal to the whole organization that not only does management embrace the idea of the hub, but by moving into one themselves, [they have demonstrated] that they’re also willing to live the talk,” McGregor said.

The hub set-up led to more idea-sharing and fostered a team mindset, McGregor said. Because they are working in close proximity to one another, team members have even benefited from what one employee described as “creative eavesdropping,” McGregor continued.

GSK hired a consultant to help frame its open innovation program, which is built around what the company describes as its “Want/Find/Get/Manage” model.

McGregor spelled it out in this way: “Want” refers to establishing a mission. “Find” describes the mechanisms that will be used to identify the external resources needed to accomplish the mission. “Get” includes establishing the processes needed to plan, structure, and negotiate the agreements for obtaining resources. “Manage” entails developing tools, metrics, and management techniques to foster external relationships.

“What Want/Find/Get/Manage says in simple terms is that if you really want to be productive, if you really want to drive growth, you need to put some structure behind open innovation,” McGregor said.

GSK is actively pursuing new ideas from outside the organization. The company teams with technology scouts from around the world, partners with technology search companies to scope out innovative ideas that can then be evaluated by GSK’s R&D team, encourages collaboration with its supplier partners, and actively participates in a variety of industry events. The company recently launched a Web site to allow external innovators to submit technologies (http://www.innovation.gsk.com).

Substantial sales growth is not the only measure of GSK’s open innovation success. McGregor shared this by-the-numbers accounting of GSK’s 2007 open innovation results. The company identified over 400 potential “finds” against a list of 45 “wants.” As of this spring, a total of 50 technologies were under review by GSK’s future teams; and 18 early-stage technology agreements had been closed.

GSK research indicates that the open innovation approach has promoted staff efficiency, reducing time lost to formal meetings and the like by 67% or 40 min/day. It also has increased company decision-making speed by 45% and improved market responsiveness by 17%.

Kraft’s Partnership Plans

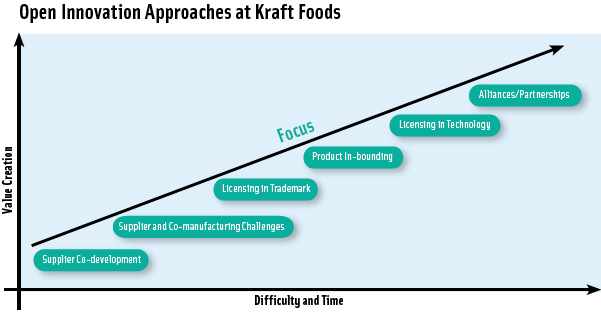

Like GSK, Kraft embarked on its first open innovation initiatives in 2006, so the process—although moving forward rapidly—is still in its infancy

“I consider open innovation to be a journey, and we’re still in the early stages of it,” said Steven Goers, Vice President, Open Innovation and Investments, Kraft Foods.

Kraft doesn’t lack for in-house research and development expertise, Goers observed, referencing its “strong internal innovation” capabilities. But confronted with the “strategic imperative” of generating more than $1.5 billion in new business revenues annually, there was a need to expand the food industry giant’s network of external resources.

“It’s not that we’re not innovative,” said Goers. “We are very innovative, but the fact of the matter is that so are a lot of other people. And the world has gotten very small in the last decade or so, and the pace of innovation has rapidly increased.

“The goal of open innovation is to accelerate Kraft’s growth by leveraging unique and relevant external solutions to meet our strategic consumer needs,” he summarized. “It’s an approach and a cultural shift that says there is most likely a solution out there that exists against our challenges,” he continued, describing the concept.

In some ways, open innovation isn’t a new idea, Goers observed. “Whereas in the past, they [strategic partnerships] were more opportunistic in nature, I think going forward it needs to be more of a business imperative that is embedded in all we do.”

As GSK has done, Kraft has taken a multi-faceted approach to open innovation. In May 2008, the company improved and relaunched its Web site www.InnovatewithKraft.com to seek product, package, and process ideas from outside the company. Goers reported that Kraft has invested in two life science venture funds to help provide early access to emerging technologies.

Establishing a clear-cut objective—i.e. knowing what consumer benefit you are seeking to deliver—is critical to the open innovation process, Goers emphasized.

“If you don’t know what you’re looking for, you’ll never find it,” he said.

At Kraft, each business unit is charged with identifying a “Top 10” list of strategic consumer needs applicable to that unit, and cross-functional teams, led by an open innovation staffer, work to identify products that address those needs.

Among the fruits of Kraft’s open innovation initiative was the rollout earlier this year of Kraft Bagel-fuls, frozen bagel sticks filled with Philadelphia cream cheese. An alert business unit executive identified the product’s potential for the packaged goods category when presented with an unsolicited product innovation.

Kraft’s open innovation team works closely with supplier partners to identify and develop new product concepts. Recent offerings born of supplier collaboration include Oreo Cakesters, LiveActive cereal, and Jell-O Fruit Passions.

Under the open innovation banner, the company has been striving to take its supplier partnerships to an even higher level. In Kraft’s “Supplier Challenge” initiative, the company invites vendor partners to generate new product or packaging concepts that address a particular consumer need or business opportunity, which Kraft presents in a detailed brief. After a vendor has presented a product proposal, Kraft has 30 days to decide whether to move forward with it. If Kraft elects not to proceed, the supplier has the right to leverage that innovation in the marketplace, Goers explained.

Open innovation has begun to pay clear dividends for Kraft, Goers reported. “We have put some runs up on the board,” he said. In 2007, he continued, Kraft launched more than 20 new products in the United States that were “enabled by open innovation,” most coming from supplier-based collaboration.

University Model Spurs Innovation

Rounding out the session on open innovation, presenter James Zuiches, Professor and Vice-Chancellor for Extension, Engagement, and Economic Development at North Carolina State University, added an academic perspective to the industry-oriented vision McGregor and Goers shared. Zuiches pointed out that scientists no less illustrious than James Watson and Francis Crick, who mapped the helical structure of DNA, were, in a sense, early beneficiaries of open innovation. At one point in their careers, the Nobel laureates shared office space with Jerry Donohue, an American physical chemist, and Peter Pauling, son of scientist Linus Pauling, also a celebrated DNA researcher.

Zuiches shared a quote by Watson, from the book, “The DoubleHelix,” in which Watson alluded to reaping benefits from the proximity of the other scientists. “The unforeseen dividend of having Jerry share our office with Francis, Peter, and me, though obvious to all, was not spoken about,” Watson was quoted as stating.

North Carolina State has established an infrastructure that supports technology exchange in a variety of different ways. The university’s Centennial Campus adjacent to its main campus physically brings together university faculty and students with more than 2,000 corporate and government employees. Nearly 400 faculty members and more than 350 students work with the Centennial Campus partners in what the university describes as a “technopolis.” Zuiches described the campus as “a national model for government, business, and university partnerships and research."

Among the Centennial Campus’s prominent government and business partnerships are the National Weather Service, Homeland Security, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Center for Pest Management, and Mead Westvaco’s Packaging Innovation Center.

Another important North Carolina State resource, the Office of Technology Transfer (OTT), established in 1984, has built a patent portfolio of 582 active patents, including 38 issued in the university’s 2007 fiscal year. Also during the fiscal year, OTT’s support of entrepreneurship facilitated the formation of five new start-up companies, Zuiches reported. Historically, the majority of the start-up companies are headquartered in North Carolina, contributing to the region’s economic development.

OTT is a success, “not just because new technologies have come out of faculty members’ labs, and we market them across the country, but—because of that connection to industry—the technology already has a potential home” [when it is unveiled], Zuiches said. North Carolina State’s programs and facilities are “literally a model of open innovation,” Zuiches summarized.

Mary Ellen Kuhn is Managing Editor of Food Technology magaazine ([email protected])

Leadership Forum Fuels Forward Thinking

When 150 established and emerging IFT leaders gathered in Chicago March 27-29 for the second annual Strategic Leadership Forum (SLF), the focus was multi-dimensional. The event was structured to provide professional and leadership development, an update on industry trends, and opportunity for input and dialog on IFT priorities—with occasions for networking and informal exchanges liberally sprinkled into the mix.

IFT President John Floros welcomed SLF attendees and reflected on the opportunity for interaction that the event provided, observing that “meeting each other and learning from each other is a key to our collective success.”

SLF participants included past and current IFT Presidents, student leaders, and members of IFT regional Sections and Divisions from throughout the United States and abroad. IFT’s emerging leadership was well represented; about half of the event attendees have been in the food science and technology profession for less than 10 years. Here’s how a sampling of SLF attendees described their experiences.

• “I am always looking for a way to better myself and gain skills that I knew would help me in my job,” said Alvina Suhendra, Senior Food Scientist at Foster Farms. “And what I learned at the IFT Strategic Leadership Forum … exceeded my expectations! The conference helps me feel more confident in myself and my leadership skills.” Furthermore, she continued, “going to [the] Leadership Forum has introduced me to current and future leaders of the food industry. Former strangers are now friends.”

• “It really opened my eyes to the issues that IFT and the food industry are faced with and [provided] good ideas and methodologies to combat those issues,” noted Daniel Colyar, student representative from the IFT Bonneville (Utah) Section.

• M. Monica Giusti, Assistant Professor of Food Science and Technology at The Ohio State University, described the SLF as “a great opportunity to re-evaluate strategies, career paths, work styles,” adding that the event was “very motivational” and “a wonderful opportunity to meet and interact with IFT professionals.”

The forum included a session titled “Innovation at IFT” that featured an update on the activities of the Task Force on Strategic Plan Implementation. In addition, session attendees used electronic polling devices to provide instantaneous feedback on a series of queries related to IFT’s priorities and future direction.

“Open space conversation” sessions also offered a chance for small group discussions about issues of importance to IFT members. One series of sessions, for example, allowed participants the opportunity to divide up for discussions on ways in which IFT can respond to trends in three areas—consumer issues, global health and wellness, and emerging science topics.

Other sessions invited discussion on topics that included membership recruitment initiatives, international careers, and IFT’s Web site redesign project.

On the final day of the Forum, attendees were treated to a presentation on “Transformation Thinking” by Steve Harvill, founder and President of Creative Ventures, a strategic and organizational consulting firm. Harvill challenged members of the audience to approach their professional and personal lives more creatively by branching out from traditional thought processes.

IFT President-Elect Sheri Schellhaass helped to bring the forum to an upbeat conclusion, urging those who attended to apply the ideas advanced at the event to their careers, the profession, and the community at large. “I encourage you to think about how you can make a difference … and then make a plan to do it,” she counseled.