Food Packaging Systems Deliver the Goods

PACKAGING

In the context of this piece, delivery means delivery of the food product to the consumer—not delivery of the closed primary package to the consumer or the retailer or the foodservice operator. That is distribution.

Delivery of product means access of the consumer to the product for consumption. Delivery means the ability to readily obtain the package contents with minimum or no application of tools or devices. Delivery means consumer convenience. Delivery means the product is not harmed or changed by the convenience of gaining access to the food contents.

Delivery of product means access of the consumer to the product for consumption. Delivery means the ability to readily obtain the package contents with minimum or no application of tools or devices. Delivery means consumer convenience. Delivery means the product is not harmed or changed by the convenience of gaining access to the food contents.

In the Beginning

Before the millennial generation, consumer safety was the prime interest of food packagers. Convenience was an incidental afterthought. Opening the package required an external device. Some hotel rooms today still have affixed to a bathroom wall frame a peculiar device that the elderly recognize as a bottle opener— a pry for crown closures on carbonated beverage bottles. And, as much as sommeliers and Iberian cork tree growers and wedding gift consultants love corkscrews, cork pull closures are still applied for many wine bottles.

Veterans of World War II and the Korean Conflict recall opening (double-seam-closed) C-ration cans with bayonets and thumb-driven can-opening devices originally engineered as personalized thumb screw replacements. Oddly enough, a not unsubstantial fraction of food cans today must still be opened with a mechanical or electromechanical device beloved by wedding gift givers: can openers. But the times they are a-changin’.

Almost all rigid and semi-rigid food packages such as cans, bottles, jars, trays, bowls, and cups are comprised of more than one piece: a body that constitutes the main structure and a smaller closure intended primarily to maintain a barrier against further intrusion or loss of contents. Flexible and paperboard packages usually are single-piece, that is, they are closed using the body of the container. But closures must also be opened to enable consumers to access the contents—and therein lies the complication.

Can Closures and Easy-Open Can Closures

Separate closures must be married to the body by mechanical or thermal methods or both. Invariably, it is essential that the body be engineered to fit the closure and vice versa. The double seam for a can is engineered so that the body seam and the closure seam intermesh and can be squeezed together to produce a hermetic seal that can withstand heat, steam pressure, liquid, and gaseous transmission. Until relatively recently, the double seam was considered the ultimate in closure unless consumer convenience was included in the equation. Not until the twentieth century did the mechanical can-opener days begin. And not until the mid-twentieth century did beverage cans begin to apply softer and more malleable aluminum for can ends in order to allow for more ready opening by “church keys,” some of which are currently ensconced in history and the memories of old-timers.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

The relative ease of cutting open the aluminum end—even overlooking the bimetallic aspects of steel ends and aluminum ends—led to the concept of deep scoring and counter-scoring the aluminum end, adding a lever, and double seaming the end to the body. By forming the lever into a ring riveted to the end, the easy-open grew into the driving thrust for canned carbonated beverages and beer. Easy-open, pear-shaped openings allowed the drinker to have a large orifice through which the beverage flowed easily when the open can was placed to the lips and mouth of the consumer and tilted.

And then came the environmentalists who shouted that the discarded ring pulls were cutting toes on beaches and clogging beaks of ducks, leading engineers back to their drafting tables. Rescoring the end configurations meant the ends were not readily removable from the can end and were pushed into the drink itself as it poured from the opening. (Wasn’t this unsanitary, asked a new generation of cover-the-top inventors?) Coupled with the conversion of can bodies from two-piece steel into cupped, one-piece aluminum, a new, inexpensive means of beverage delivery exploded on the American scene. And so per capita consumption of carbonated beverages and beer began its exponential growth from the late 1960s through the beginning of this century.

Not to be outdone in easy-open liquid delivery, still beverages were packaged into two-piece aluminum cans with easy-open ends, but with the added caveat that the hot filling was complemented by liquid nitrogen that rapidly expanded to fill the headspace to counter the paucity of internal pressure that would otherwise exist with the vacuum of a hot fill. Two-piece aluminum cans quickly replaced the church key-opened steel cans, and another driver for growth of still beverages in cans was under way.

Food Cans

Meanwhile, watching the aluminum can cannibalize drinks, steel can interests counterattacked, first with easy-open aluminum ends on steel bodies, but this time were stymied by bimetallic effects. Steel easy-open ends were not easy-open for hot vended cans of prepared foods because of the metallurgical properties of the harder steel and inability to score and partially cut through the steel. And not until much later when the can and can-end edges were folded under to prevent finger and tongue cuts did this concept receive much attention. And so retorted and hot-filled food cans drifted into plastic ends and even microwaveable plastic bodies with full-panel, easy-open aluminum ends plus plastic overcap and now peelable flexible lamination ends for in-vehicle eating and sipping (e.g., Campbell’s Soup at Hand) and retortable trays with peelable, heat-sealed lids.

And from Europe came two-piece ends whose rim is double seamed to the can body but which contains a large opening covered with a heat-sealed, barrier-flexible material that can be peeled back with a finger pull to open almost the entire end for spooning or forking the contents. This is a technology that awaits further market development.

But the largest advance as measured by unit volume is the full-panel, easy-open steel end finally developed and commercialized after more than 100 years by Campbell’s Soup for its soups and pasta products for kids. Soon, perhaps even sooner than many food packaging technologists might imagine, all food cans will be seal-closed with full-panel, easy-open ends and with plastic overcaps that are easy to reclose. It will mark a new era and the relegation of the wedding gift electric can opener to the museum of crown pries, corkscrews, and church keys.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Plastic Bottle

Tamper evidence and resistance did not usher in the era of plastic bottles that were easy to open and reclose, but the coincidence of their virtually simultaneous debuts suggests that many of the concepts were hardly unrelated. From the early days of pump spray-and-squirt closures for personal care products such as shampoo, deodorant, and liquid soap came a trickle of food products applying the same technologies.

Reasons for the slow adoption of the dispensing closures included inability to change the innate viscosities of the contents such as jellies, peanut butter, and ice cream toppings. Consumers, accustomed to the mouthfeels of such fluid products, were unwilling to compromise their standards for altered products to gain a benefit of ease of dispensing. Further, food scientists had difficulty in modifying formulations to deliver familiar products in different delivery systems. And residuals often lost moisture and clogged nozzles and permitted growth of mold in the surfaces near the bottoms. And who among the food packaging technologists of the 1980s and 1990s could bring themselves to invert bottles as was common in Europe to keep the contents near the closures? And which plastics engineers could figure that their favorite high-density polyethylene did not have much barrier property and that polyester had to be rendered more flexible to allow squeeze pressure to push product out of nozzles?

But each problem was individually resolved, and this decade has witnessed Heinz moving its ketchup out of traditional narrow-neck glass bottles with twist-off metal closures and whack-the-bottom dispensing into squeeze polyester bottles with dispensing nozzles. Some of the nozzles are even self-closing as are the delivery systems for salad dressings and paste seasonings.

In fact, relatively few pumpable or squeezable fluid or liquid foods today are not in squeezable bottles with small openings in the closures through which the product flows for ease of dispensing—and what remains will shortly convert. And do not ever forget the pump dispensers for liquid salad dressings—the spritzer.

Spices, salt, and seasonings have followed the lead of peppercorns by packaging the pristine, intact contents in bottles with steel grinders in their closures in order that the consumer may freshly grind the flavoring directly into or onto the product to be spiced or seasoned. This type of package seems to be the reversal of convenience, but appears to be preferred since it allows for the delivery of what is perceived to be very fresh product.

IFT Achievement Award

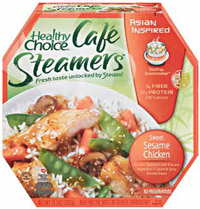

At the recent IFT Annual Meeting & Food Expo®, ConAgra won the Food Technology Industrial Achievement Award for its Healthy Choice Café Steamers, a packaging system for convenience in preparation using a combination microwave heating and steaming of frozen prepared foods. And why shouldn’t the grand prize go to a packaging system adapted very carefully from practices applied in manual form by microwave food folks for decades? Because aren’t packaging and delivery an integral component of food science and technology?

The devices described in this piece are but a sampling of how food packaging technologists have been delivering delivery systems for food products that protect as they foster access for consumers —and signal more and more readily delivered food.

by Aaron L. Brody, Ph.D.,

Contributing Editor

President and CEO, Packaging/Brody Inc., Duluth, Ga.,

and Adjunct Professor, University of Georgia

[email protected]