The Dairy Chronicles

Dairy experts at the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Center for Dairy Research explain why cow’s milk is a near-perfect beverage and perhaps the most versatile ingredient.

Article Content

There are products in the dairy cases of grocery stores that look like milk and cheese and are labeled milk and cheese but are not milk and cheese. They are plantbased dairy alternatives being promoted as nutritious, eco-friendly, and cruelty-free alternatives to dairy. Many consumers are convinced that these plant-based dairy alternatives are equivalent to or better than dairy products, but are they? Using their firsthand knowledge of the unique properties of cow’s milk and other dairy products, the dairy experts at the Center for Dairy Research (CDR) at the University of Wisconsin–Madison (UW–Madison) highlight the virtues of cow’s milk and other dairy products and explain why dairy products are nutritionally and functionally superior to plant-based dairy alternatives and why plant-based dairy alternatives are not always so clean and green.

An All-Natural Beverage

“We consider [dairy milk] to be one of the most unique foods that comes from nature,” says Kimberlee Burrington, coordinator for dairy ingredients, cultured products, and beverages at the CDR. “It has protein, it has carbohydrates, [and] it has lots of vitamins and minerals, which is very unique for one particular food to have.” In fact, dairy milk is designed to contain every fat, every protein, every vitamin, every mineral, and every growth factor necessary for children to grow and develop properly. Specifically, milk is a natural source of high-quality protein including all nine essential amino acids; thiamin, niacin, folate, vitamin C, and other vitamins; calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, and other minerals; carbohydrates; and fatty acids. “Dairy milk is a complete food,” says John Lucey, a professor in the Department of Food Science at UW–Madison and director of the CDR. “It’s a package that is designed to provide growth and make healthy individuals. … Nothing else out there—no plant, no seed, no anything—has that in mind.” And unlike other nutrientdense beverages, dairy milk does not contain a lot of calories. “We’re getting a lot of these key important nutrients, but we’re not consuming a vast amount of sugar or calories when we do so,” Lucey says. “That’s important.”

Besides being relatively low in calories, dairy milk is one of the most minimally processed beverages available: Cows produce milk, farmers milk cows, and then the milk is sent to dairy processing plants. At dairy processing facilities, “there is some fat removal because you’re trying to adjust to making maybe a 1% fat milk or a 2% fat milk,” Burrington explains. “After that, you pasteurize the milk to make the product safe, and then it’s bottled. So there’s actually very little processing involved.” The purpose of pasteurization is to destroy pathogens in milk and to kill spoilage microbes that may be present in milk. During pasteurization, dairy milk is typically heated at a temperature of either 145°F for 30 minutes or 161°F for 15 seconds. “From a safety point of view, the most important step is the pasteurization step,” Lucey says. “That step is designed to kill all pathogens present in the milk so that it is safe for us to consume as long as everything is done in a sanitary fashion and the milk is cooled.” Milk is also homogenized, fortified with vitamin A (only low-fat and skim milk) and vitamin D, and tested to ensure no antibiotics are present at dairy processing facilities. All of these steps ensure that cow’s milk is safe to consume, antibiotic-free, and has a longer shelf life.

A Highly Versatile Ingredient

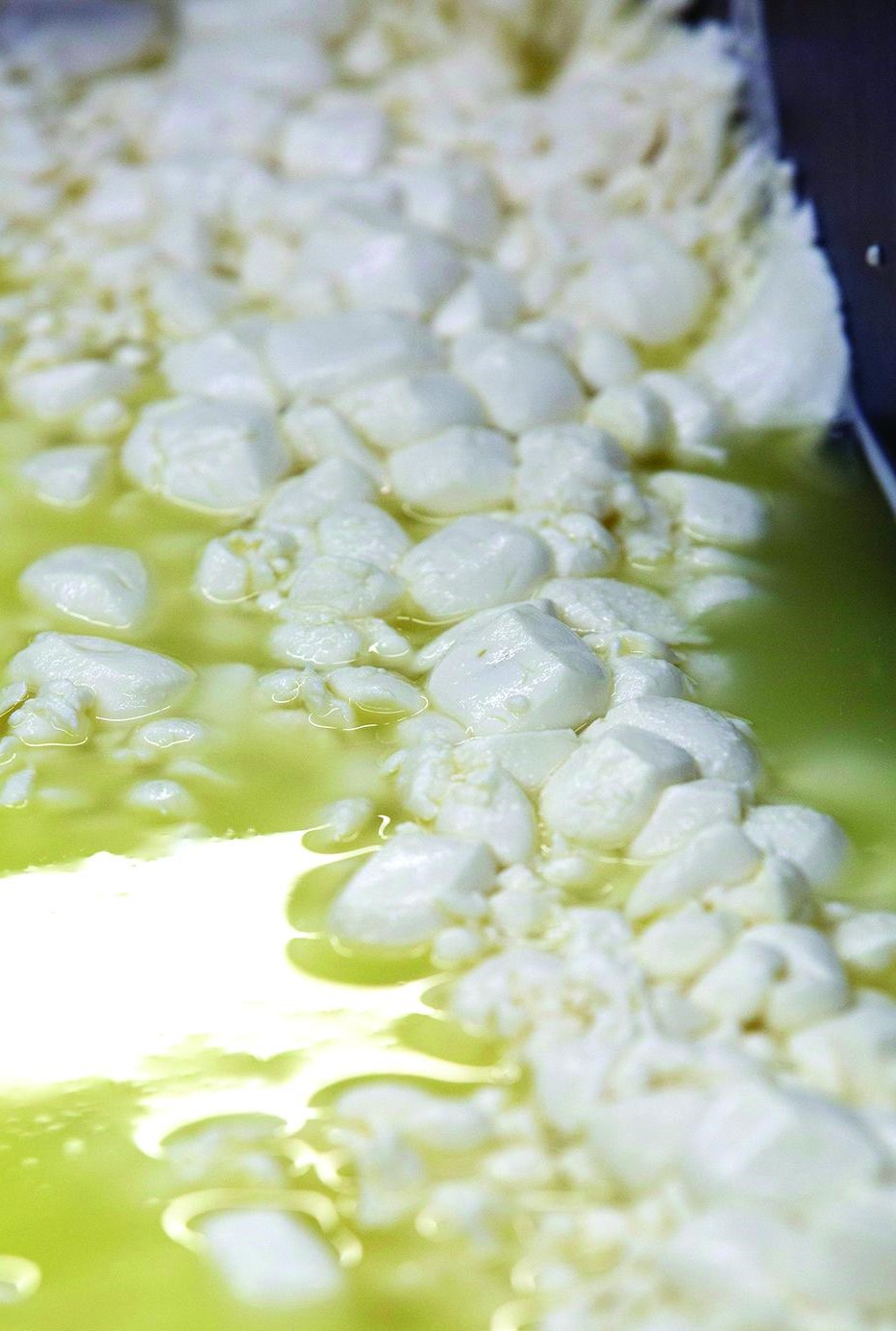

Dairy milk is not just a highly nutritious beverage; it’s also a versatile ingredient. “From the same starting milk, we can end up with maybe 500+ different varieties with different flavors and textures,” Lucey marvels. “We can make an almost endless supply of different types of diversity, which is amazing from one product.” It is the primary ingredient for a variety of delicious dairy products such as butter, ice cream, yogurt, and cheese. Cheese, the second mostconsumed dairy product in America and the most diverse, has a serendipitous origin: “We borrow the process of making cheese from the cow and the calf,” Lucey explains. “When a calf suckles the cow and drinks milk, [the milk] goes into one of the stomachs of the calf. In one of the stomachs of the calf, he or she produces an enzyme called rennet that … clots the milk into a soft little gel.” That soft gel allows the calf to fully digest all of the nutrients present in milk. “That is what nature created— this kind of cheesemaking process inside the stomach of the calf,” Lucey adds. “That was the basis of the cheesemaking industry.” A mixture of enzymes produced in the stomachs of young ruminants (e.g., cattle, goats, sheep, and camels), rennet is an essential ingredient in making cheese as it coagulates the proteins in milk, producing curds and liquid whey. Calf rennet has been used to make cheese for thousands of years, but modern cheesemakers can choose from different types of rennet to make cheese:

• Animal-derived rennet. Animalderived rennet, which originates in the fourth stomach of ruminant animals, is the most expensive milk coagulant.

• Microbial rennet. This is a coagulant produced by a specific mold or yeast grown in a laboratory, so it is vegan-friendly but tends to produce cheeses that can be somewhat bitter (particularly aged cheeses).

• Fermentation-produced chymosin (FPC) rennet. FPC rennet is a microbial rennet produced by taking the rennet-producing gene from ruminant DNA and inserting it into bacteria, mold, or yeast cells. The transplanted gene then produces chymosin in the host cell, which means that FPC rennet is a genetically engineered product.

• Vegetable rennet. Vegetable rennets are plant-derived enzymes that can coagulate milk; however, they can also cause bitterness in cheeses.

• Citric acid and/or vinegar. These are used to make cheeses such as ricotta.

Cheeses that have unique and complex flavors such as aged cheddars, Gouda, Gruyère, and Parmesan require more than simply adding rennet to milk and separating curds from whey: Various cultures (lactic acid bacteria) are added early in the cheesemaking process, either before adding rennet or at the same time. The cultures convert the lactose in milk to lactic acid, which lowers the pH of the milk and aids in breaking milk proteins into compounds that provide each type of cheese with its distinct flavor. “The flavors that are created in cheese depend on how we make the cheese and what cultures or enzymes we use to make the cheese,” Lucey says. “Basically, it’s created by the cultures/fermentation. Like wine and like other kinds of products, it’s the fermentation that, over aging, creates these products.” During the ripening stages of certain cheeses (e.g., Brie, Camembert, and Gorgonzola), mold plays a role in developing and enriching the flavor. So cheese, unlike pasteurized dairy milk, is a live product. The type of culture, the amount of whey removed, the pressure applied to curds, the duration of aging, the presence or absence of mold all factor into the type of cheese that the cheesemaking process yields. “All of the bacteria and enzymes are continuously creating new flavor compounds in the product. It takes time, though,” Lucey says.

The Dairy Debate

No one can dispute the deliciousness and versatility of cheese and other dairy products because of their variety of different flavors, textures, and consistencies. But recently, milk and other dairy products have come under fire for everything from the fact that they contain lactose to the welfare of the animals on dairy farms. Some dairy opponents point out that humans are the only species that consumes milk, and its derivative products, throughout adulthood, yet most people around the world are lactose intolerant. It may therefore seem that humans should not consume milk and other dairy products after a certain age. “Many cultures don’t grow up drinking milk, so they tend to have more lactose intolerance issues. But milk can be made suitable for all populations,” Burrington observes. She and Lucey maintain that milk, cheese, and other dairy products provide high-quality nutrition, which humans have needed since the beginning of time. “What we should realize is that … we have been using cows as a source of nutrients for us for a long time. This is not a recent phenomenon. [Milk] adds diversity and variety to our lives, and that’s why it’s been so popular for all this time,” Lucey asserts. “Yes, some people are lactose intolerant; actually, they’re probably more of what [nature intended]. All of us—apart from some very rare individuals—are designed to consume lactose when we’re infants. The content of lactose in breast milk is about 7%, which is nearly twice the amount in cow’s milk.”

When humans are young, the lactose in milk is broken down by an enzyme (lactase) produced by the cells lining the small intestine. For most individuals, the production of lactase decreases as they age, which causes them to become lactose intolerant over time; however, most people retain some lactase activity in their intestines, allowing them to consume limited amounts of lactose. “If people have problems with lactose intolerance, what that actually means is that there’s probably still some enzyme activity (even if they’re lactose intolerant), but they can’t consume a large amount of lactose,” Lucey explains. Because cheese, yogurt, and other dairy products made with lactic acid bacteria contain little or no lactose, people who are lactose intolerant can eat these dairy products without experiencing the symptoms associated with lactose intolerance (e.g., gas, bloating, abdominal discomfort, etc.). “Yogurt is a very fine product for people who have lactose intolerance. The other is cheese because during the fermentation process of cheese,” Lucey says, “the bacteria we use to … make cheese ferment the lactose. So by the time the cheese is made, almost all the lactose is gone.” Lactose is especially low in hard aged cheeses such as cheddar, Parmesan, and Swiss; in fact, the longer a cheese is aged, the lower its lactose content. There are also milk and dairy products that are lactosefree such as Lactaid milk.

Many dairy opponents take issue with the welfare of dairy animals and the sustainability of dairy farming. Though brief, the lives of dairy cows are filled with a considerable amount of care and attention in a concerted effort to produce safe, high-quality dairy products. This may include raising livestock indoors to protect them from a variety of antagonistic factors that would compromise their safety, health, and well-being. Moreover, dairy farmers have a significant incentive to treat their animals well: cows in poor health cannot produce high-quality milk for dairy products. Perhaps for this reason more than any other, dairy farmers work with scientists at the CDR and other dairy researchers to implement the best methods to produce and raise dairy cows, harvest milk, and preserve product. Dairy farming and dairy products have been around for thousands of years—a true testament to their sustainability.

Dairy Alternatives

There are also individuals who are not concerned about lactose intolerance or dairy farming practices but simply want to eat fewer animal products. These consumers believe that plant-based dairy alternatives are more nutritious and “cleaner” or better for the planet. In response to this and the other concerns, product developers have created dozens of dairy alternative beverages made from almonds, cashews, coconut, hemp, oats, rice, peas, and soy. Most are marketed as “milks” that are healthier than cow’s milk and more compatible with clean label values. “Plants cannot produce milk,” Lucey declares. “Technically, milk has a standard, according to federal regulations, that it has to come from a mammary gland. So these [beverages] shouldn’t, according to federal standards, be called milk.” Because plant-based dairy alternative beverages are produced by juicing or otherwise manipulating the fruits of trees, they should probably be called juices. And from a nutrition standpoint, the only plant-based dairy alternative that comes close to having the nutrient content of cow’s milk is soymilk. “Milk typically per serving (which would be an eight-ounce glass) [has] eight grams of protein. The other types of plant-based milks typically won’t have that much. They might have two grams, four grams, five grams,” Burrington explains. “The other big difference is how they look in terms of the Percent Daily Value. All of them have to take into account the … quality of the protein that they’re using, and that directly translates into a lower percentage of the daily value. So even if they had eight grams of protein, it wouldn’t translate into the same protein quality or the same level of the daily value requirement.” This is because animal products are a better source of amino acids than plant foods, and dairy foods and other animal products are the only natural sources of vitamin B12. “By and large, [plant-based dairy alternatives] have less protein, less key fatty acids, less calcium and … vitamins and key nutrients,” Lucey says, which means that all plantbased dairy alternatives must be fortified with calcium, B vitamins, potassium, and other key nutrients that are naturally present in cow’s milk.

Nutrients are not the only things added to plant-based dairy alternatives. “I think that consumers that are using the plant-based milks are also the consumers that are very focused on clean label,” Burrington observes. “It isn’t easy to make a beverage out of an almond or a cashew or an oat. You have to add a lot of different ingredients to that.” Those ingredients include sugar, emulsifiers, stabilizers, thickeners, and other additives to turn what would otherwise look like a cloudy, watery solution with sediment on the bottom into a beverage with the smooth consistency and pleasant taste of cow’s milk. The processing steps for plant-based dairy alternatives include soaking the seed or plant material in water, grinding the seed, separating oil bodies from other plant materials, thermal processing to inactivate harmful or degradative bacteria, homogenization, and adding sugar and functional ingredients (vitamins, minerals, flavors, colors, preservatives, etc.). “Usually, [plant-based dairy alternatives] have to undergo things like pH adjustment, acidification, grinding of the plant if it’s a seed, [and] extracting into some sort of solution. Enzyme treatments are quite common so that they’ll chew up the proteins or plant materials to extract some of the nutrients from it. So there will be a variety of extractions, enzymes, chemical treatments either with acid or alkali to try to release some of the nutrients that are of interest in that plant material,” Lucey says.

Recently, some pediatric and nutrition associations have taken a stance that may give pause to those who claim plant-based dairy alternatives are better than cow’s milk. The American Academy of Pediatrics, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, and the American Heart Association have advised parents to avoid substituting plant-based dairy alternatives for dairy milk for children ages 1–5 unless the child is allergic to dairy. “Young kids [and] babies have extreme requirements for key nutrients because they’re growing substantially and so rapidly at that time. So they need a lot of key nutrients, and they also need a lot of energy because they’re growing at a rapid rate,” Lucey says. “[Human milk] and [cow’s milk] have essentially the same components. …The only difference between human and cow’s milk is the ratio of certain components: Some are lower in cow’s milk, some are higher in human [milk], and vice versa. But basically, they have the same components.” Burrington agrees: "Virtually none of those plant-based products would contribute enough of the essential amino acids for that age group to be able to grow and develop normally. Unfortunately, if you do have a family that wanted to feed their children plant-based milks, it would actually end up slowing their growth and development.” It seems dairy milk is the best choice for proper development, wholesome nutrition, and foods with incredible taste appeal such as cheese, ice cream, and pizza. But consumers may not be getting that message. “We … as a dairy industry are trying to do a better job of educating consumers on what is really in milk and what really are the benefits of milk,” Burrington admits. “We focus a lot of our time on trying to do that.”

While educating consumers has become increasingly important to the CDR, its main purpose is to educate dairy professionals, grow the dairy sector, and increase the demand for dairy products. The CDR provides training to industry professionals on a variety of dairy products (milk, cheese, ice cream, yogurt, etc.) and on safety. Every year, about 1,400 people visit the center for training. “Our job here is to do applied research on dairy products, work with companies if they want to develop a new product, work with students that want to work in dairyrelated areas, and transmit this knowledge to the industry,” Lucey says. The CDR also offers the Wisconsin Master Cheesemaker Program, which provides experienced cheesemakers with the opportunity to learn more about the science behind dairy and cheesemaking. The center brings in cheese experts from around the world to teach courses about how cheeses are made in different countries, teaching them the tricks and techniques for making a variety of cheeses. “The result is that now, over 50% of the specialty cheeses made in the [United States are] made in Wisconsin. We produce over 800 million pounds of specialty cheese every year. For me, that’s a great success,” Lucey says proudly. And as the dedicated staff at the CDR continue to conduct basic and applied dairy research and training, there are sure to be more successes in the dairy industry in the future.