Doing Good While Doing Well

What’s needed to advance sustainability goals and improve trust in the food system? Here’s a step-by-step approach to effecting successful change.

Article Content

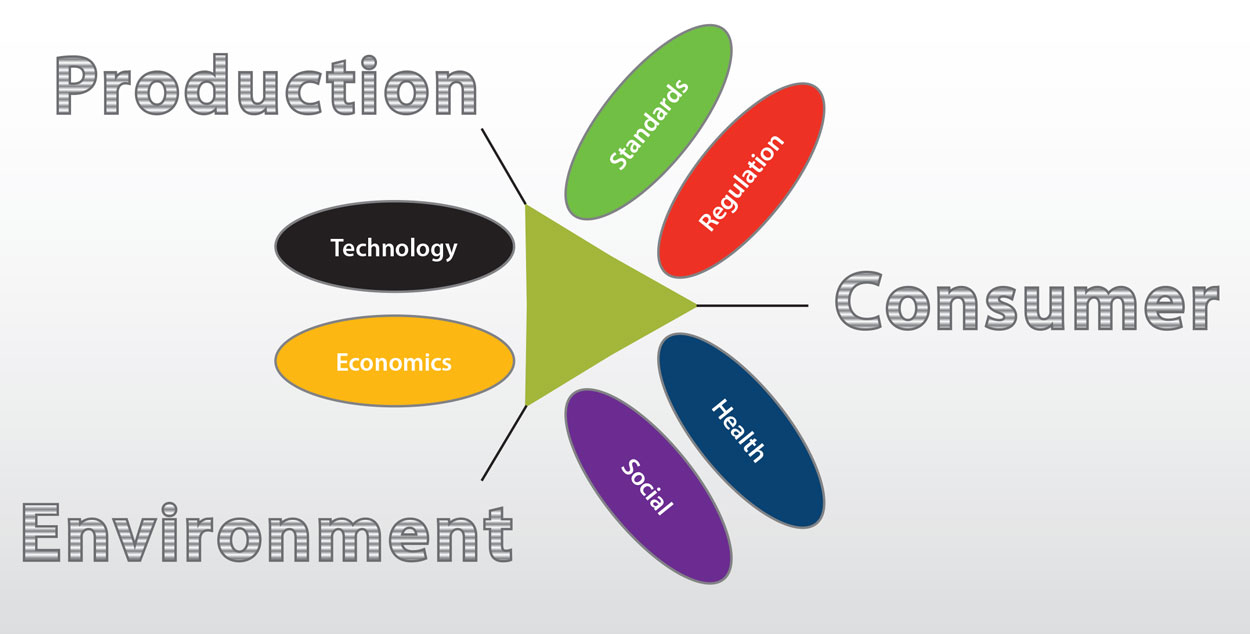

Food systems are at a nexus of interactions among multiple other systems (Figure 1). A good measure of the complexity of such interactions is the fact that at least 12 of the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals have indicators related to food or nutrition (Liu et al. 2018). This complexity, unprecedented changes in consumption, and pressure to innovate call for a radically new approach by food businesses and society to address two key aspirations: 1) achieving optimal food system sustainability (economic, health, and environment) and 2) improving trust in food systems. The following steps would help attain these goals: rethinking business metrics and reporting, including a move to outcome metrics; designing food information systems for more transparency; creating adaptable food regulations and standards; and introducing more multidisciplinarity.

Rethinking Business Metrics and Reporting

There have been many calls for food value chains to include more of the social, health, and environmental costs associated with food production and consumption. Currently, many such costs are considered by economists to be externalities (defined as situations when the effect of production or consumption of goods and services imposes costs or benefits on others that are not reflected in the prices charged for the goods and services being provided) (Khemani and Shapiro 1993).

The potential magnitude of health and climate change externalities is certainly large. The warnings in both cases are dire, summed up by statements such as that of natural historian Sir David Attenborough in 2018: “If we don’t take action, the collapse of our civilisations and the extinction of much of the natural world is on the horizon.” The connection between food consumption and climate change was underlined vividly by the recommendation of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: “Buy less meat, milk, cheese, and butter and more locally sourced seasonal food—and throw less of it away” (IPCC 2018). Similarly, the global burden of noncommunicable diseases was projected by the World Economic Forum and the Harvard School of Public Health in 2011 to cost over $30 trillion up to 2030, which was the equivalent of almost 50% of global GDP in 2010 (WEF 2011).

While the preceding reports are dramatic, the remedies proposed will not be successful unless other factors are taken into account. A more holistic approach is required, factoring in the acceptable trade-offs needed when multiple systems interact. In addition, a growing number of studies have been published on the harmful effects of food processing (Lawrence and Baker 2019). While historical consensus points to examples of food processing causing harm (e.g., trans fats from partially hydrogenated oils), the conversation has become unbalanced. In line with demands for multiple dimensions of value for consumers coupled with the need for sustainability, there is a need for a balanced science of food processing that is based on objective, up-to-date evidence. There is arguably a research gap in defining what an optimal roadmap for overall evolution of food technology would look like, taking into account as a minimum the four parameters: food safety, sensory quality, nutritional quality, and environmental impact. Today’s scientific tools have done much to improve understanding of the limitations and strengths of traditional cooking and processing technologies. This is a dilemma, as the food industry, more than most industries, faces the challenge of consumer fear of new technology. Thus, the availability of effective new technologies does not mean they can be used commercially. Until now, food manufacturing has lagged behind other industries in implementing the tools of Industry 4.0. (Industry 4.0 is a term used to describe the fourth industrial revolution, whereby conventional business systems are enhanced by emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, and robotics, to transform business models) (Schwab 2016). This is likely to change following the COVID-19 crisis, with potential benefits for multiple food system stakeholders.

During the past decade, there has been a re-examination of corporate purpose in a number of institutional and corporate settings. For example, the British Academy concluded, “Corporations were originally established with clear public purposes. It is only over the last half century that corporate purpose has come to be equated solely with profit. This has been damaging for corporations’ role in society, trust in business, and the impact that business has had on the environment, inequality, and social cohesion. In addition, globalisation and technological advances are exacerbating problems of regulatory lag” (Mayer 2018).

There is, thus, an argument for a shift from economics of “profit maximization” toward “value maximization.” This is captured in the movement known as “impact economics” (Cohen 2019). Corporate social responsibility programs were set up to address a broad range of issues but often became separated from the business and were uncoupled from the value creation process. According to Browne at al. (2016) this was significant as a company’s value should factor in future value. (About 30% of a company’s value is at risk in this way from reputational impacts, accidents, government regulation, etc.)

How might this be translated into the world of food production? Compared with other industry sectors, food production is ideally positioned to respond to changing definitions of value. Responsible food businesses recognize and engage with multiple stakeholders. For investors and other interested stakeholders, a range of reporting recommendations are available to food companies wishing to publish environmental social and governance information (WBCSD 2018). One trend that transgresses businesses sectors is the expansion of the meaning of capital to incorporate the bigger picture of businesses at work in society and the world (Roche and Jakub 2017); this includes human capital, social capital, natural capital, and shared financial capital. This approach offers a good way to align the expanded measures of corporate performance. (See sidebar at left.) While the expanded models of reporting are evolving rapidly, there is still a lag in streamlining data capture using new technology.

In conjunction with new ways to measure performance, there is an emerging opportunity to introduce more outcome measures. Trust is an important outcome, but difficult to measure. It is also a lagging indicator, a product of what is done and how it is done. The recent Edelman report found ethics to be the overwhelming driver of trust in companies rather than competence (Edelman 2020). This puts a spotlight on how companies work rather than their technical skills. This observation again calls for a different way of measuring performance. Thanks to new technologies such as next generation sequencing, capability is emerging that can improve the public health outcome measures of relevance to food. This is a huge opportunity for risk-based regulation and also a tool to better pinpoint the behavior of hazards in supply chains.

Food Information Systems for More Transparency

There are numerous information asymmetries at present that make life difficult for all the stakeholders in the food value chain: consumers, industry, government, producers, etc. A lack of food chain transparency led to limited food business and regulatory foresight and contributed to recent food fraud and food safety incidents (Brooks et al. 2018). There is thus growing interest in designing systems to improve transparency of food systems to build consumer trust and to support better preventive controls on the part of food businesses (Schiefer and Deiters 2013).

There is no doubt that modern improved traceability systems (the ability to follow the path of a food material or one of its attributes through a supply chain) have saved many lives and limited the harm done to food businesses during food safety incidents. However, traceability is not the same as transparency. The advent of new tools to support traceability, such as distributed ledger technology, will not necessarily increase transparency. To be successful, transparency systems will need to be structured and purposeful. Unstructured, untargeted approaches to transparency may lead to confusion and even increase mistrust (Schiefer and Deiters 2013). Systems will also need to be adaptable and dynamic, delivering the right information at the right time and of the right quality. The optimal approach will build trust, find common ground, and facilitate stakeholder collaboration. In addition to improving transparency, digital platforms enable the transition from a narrow focus on food safety and nutritional quality to the management of multiple outcomes of the type highlighted here (Martindale et al. 2020). This is a radically more sophisticated model for the governance of food value chains than traditional approaches.

There are particular opportunities for much greater transparency, metrics, and monitoring in the areas of animal welfare, fisheries, crop production, and food packaging. This will necessitate the development of better monitoring tools and metrics, supported by appropriate data management and standards.

Adaptable Food Regulations and Food Standards

The past two decades have been characterized by the introduction of significant new approaches to food regulation in every part of the world—for example, the Food Safety Modernization Act in the United States and General Food Law in the European Union. New regulations have placed risk assessment and prevention at the core of food safety management and provide clarity on the responsibilities of food businesses and regulatory authorities.

Globally, the most comprehensive and ambitious regulation to propose rules on transparency in the area of food is the recently published (EU) 2019/1381, which will apply beginning March 27, 2021. The new regulation was a response to the “fitness check” on European Union General Food Law (EC 178/2002). One of the findings of the review was a perception of lack of transparency in the risk analysis process, which affected trust in the regulatory process. In response, the new regulation makes provision for improvements in risk communication to strengthen citizen trust, and somewhat controversially, applicants (and contract research organizations) will be obliged to notify the European Food Safety Authority when beginning studies designed to support a regulatory submission. All reports of such studies will be published. The regulation is far-reaching as it includes provision for technical visits by regulatory experts to laboratories conducting the studies. While it may be useful to make regulatory provision for such visits, the rule at first sight appears not to avail of the opportunity of the principle of mutual recognition of international Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) standards. Perhaps it may encourage more laboratories to achieve GLP certification or, indeed, serve as a driver for new standards that make responsible R&D more efficient. However, it remains to be seen if the approach will serve the purpose of increasing trust without hindering innovation.

The British Academy (2018) highlighted regulatory lag as a challenge in reforming business (Mayer 2018). This has always been true, however. Of more concern is not the lag but the increasing gap due to acceleration of technological development and the abilities of societies to respond, the so called “pacing problem” (Marchant et al. 2011). This calls for supplementary approaches to traditional regulation. A number of responses are possible, including the following:

1) Planned adaptive regulation, which recognizes the need to keep up with changes in science and technology (IRGC 2016).

2) Recognition of voluntary systems, such as compliance with appropriate internal regulations, and private and public standards.

3) Application of proportionate approaches to improve efficiency, such as “polluter pays” or incentives, such as less inspection for high-performing businesses.

Some consortia are developing guiding principles that, while not mandatory, can serve as a template for rapidly identifying unmet needs of stakeholders, including consumers (Goldberg 2020). Realistically, there is a limit to the number of standards that a value chain could and should sustain. There are undoubtedly too many private standards currently, and they are of variable quality. A consolidation process would benefit food producers, consumers, and regulators. However, there are a few standout areas where there are huge changes in consumption undermined by a shortage of standards. These include vegan foods, biodegradable packaging, and novel botanicals such as CBD oil.

The media has made much of perceived differences in food regulations between jurisdictions, notably the United States versus the European Union. The frequent assertion that EU food regulations are more stringent is not borne out by analysis (IRGC 2017). In some cases, EU regulations are more demanding, and in others, it is the U.S. rules that are more rigorous. As risk-based approaches become more commonplace, it can be expected that regulations will converge. In the meantime, there is an underused opportunity for international collaboration in food risk analysis that would benefit all stakeholders by sharing best practices.

‘Multidisciplinarity’: Opportunities for Food Science and Technology

The sciences and technologies of food have always had to reach across disciplines to find the optimal solutions to meet consumer and business expectations. That trend continues with the increasing application of social sciences to address modern challenges facing food production and consumption. There is an opportunity to go further in bringing expertise from the humanities to support a more trustworthy, ethical food system (Goldberg 2020). A handful of initiatives has started to bring diverse disciplines together, the most noteworthy of which is “Choose Food” hosted by the Berman Institute of Bioethics at Johns Hopkins University (www.choosefood.org).

Responsible manufacturers are guided by asking their own questions proactively to scope out steps in the value chain that require improvement in advance of amplified public debate. This approach is not as efficient as cross-sector collaboration to identify challenges, opportunities, and potential remediation pathways. Professional bodies such as IFT are ideal networks to draw together the necessary insights to identify best practices and the trade-offs needed for optimal functioning of food value chains. In keeping with the complexity of food systems and society expectations, a new level of “multidisciplinarity” is needed that could unite different professions to collaborate on the grand challenges of the food-health-environment nexus. The easiest path for such collaborations would be via the appropriate professional associations, supported by digital communication platforms.

Availing COVID-19 Crisis Learnings

“Never let a good crisis go to waste” is advice often attributed to Winston Churchill.

What are the learnings for the food sector from the experiences of the pandemic? The poor functioning of the science policy and risk assessment/risk management interfaces during the COVID-19 crisis (Makarow 2020) undoubtedly contain lessons for all professionals concerned with risk analysis, including food. The crisis has exposed vulnerabilities in food chains that were not foreseen and has opened a new debate about dependency on global supply chains (Hirtzer and Skerritt 2020).

There is an acceleration of trends such as online shopping and home food delivery that were already underway. While food manufacturing in general was slow to adopt the tools of Industry 4.0, that is changing. Already robotics are being rapidly deployed in crop growing and harvesting. The current disruption will accelerate implementation of robotics and remote inspections in food control. While the deployment of new technology will require capital investment, there will be multiple returns, including worker health, product quality, animal welfare, sustainability, product safety, and more. The measurement and reporting of such impacts will support the investments needed. Finally, digital data trails associated with e-commerce enable closer examination of vulnerable parts of the supply chain and offer more transparency than traditional systems.

A View to the Future

Food manufacturing and production systems now face their greatest challenges and opportunities. The tools necessary to achieve the next food revolution are already available and will need to be deployed in a practical, structured way. The necessary steps are summarized as follows:

• Addressing the challenges of sustainability and stakeholder trust requires a multipronged approach, exploiting new metrics of corporate performance and applying new digital platforms.

• More food systems transparency and data sharing supported by new digital platforms can benefit operators (e.g., better preventive controls) and underpin consumer trust.

• Food regulations are evolving and becoming more risk-based, but more international cooperation would benefit all stakeholders by identifying best practices.

• Adaptable regulation and appropriate voluntary standards are needed to support accelerating innovation.

• Professional associations have an opportunity to support more cross-disciplinary collaboration in the area of food, especially among traditional sciences and the humanities.

• Food systems should take advantage of the learnings and opportunities arising from the COVID-19 crisis.

REFERENCES

Attenborough, D. 2018. Speech presented at COP24, Katowice, Poland, Dec. 3.

Brooks, S., C. T. Elliott, M. Spense, et al. 2017. “Four years post-horsegate: an update of measures and actions put in place following the horsemeat incident of 2013.” npj Science of Food. 1:(5). doi: 10.1038/s41538-017-0007-z.

Browne, J., R. Nuttall, and T. Stadlen. 2016, Connect: How Companies Succeed by Engaging Radically with Society. London: W. H. Allen.

Cohen, R. 2018. On Impact. A Guide to the Impact Revolution. www.onimpactnow.org.

Edelman. 2020. 20th Annual Edelman Trust Barometer. Daniel J. Edelman Holdings. www.edelman.com.

EU. 2019. Regulation (EU) 2019/1381 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the transparency and sustainability of the EU risk assessment in the food chain and amending Regulations (EC) No 178/2002, (EC) No 1829/2003, (EC) No 1831/2003, (EC) No 2065/2003, (EC).

Goldberg, A. M., ed. 2020. Feeding the World Well: An Ethical Framework for Food Systems. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. In press.

Hirtzer, M. and J. Skerritt. 2020. “Americans on Cusp of Meat Shortage With Food Chain Breaking Down.” Bloomberg, April 28.

IPCC. 2018. Global Warming of 1.5°C. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Geneva, Switzerland. ipcc.ch.

IRGC. 2016. Conference Report. Planning Adaptive Risk Regulation. International Risk Governance Council, Lausanne, Switzerland. irgc.org.

IRGC. 2017. Transatlantic Patterns Of Risk Regulation. Implications For International Trade and Cooperation.

Khemani, R. S. and D. M. Shapiro. 1993. Glossary of Industrial Organisation Economics and Competition Law. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris. oecd.org.

Lawrence, M. A. and P. I. Baker. 2019. “Ultra-processed Food and Adverse Health Outcomes. Fresh Evidence Links Popular Processed Foods with a Range of Health Risks.” Brit. Med. J. 365: l2289.

Liu, J., V. Hull, H. C. J. Godfray, et al. 2018. “Nexus approaches to global sustainable development.” Nature Sustainability 1: 466–476.

Makarow, M. 2020. “Scientists have to seize their moment in the spotlight.” The Times, May 1.

Marchant, G. E., B. R. Allenby, and J. R. Herkert, eds. 2011. The Growing Gap Between Emerging Technologies and Legal-Ethical Oversight: The Pacing Problem. New York: Springer.

Martindale, W., L. Duong, T. A. Hollands, et al. 2020. “Testing the Data Platforms Required for the 21st Century Food System Using an Industry Ecosystem Approach.” Sci. Total Environ. 724: 137871. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137871.

Mayer, C. 2018. “Reforming business for the 21st century.” The British Academy, Oct. 31. https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/blog/reforming-business-21st-century/.

Roche, B. and J. Jakub. 2017. Completing Capitalism. Heal Business to Heal the World. Oakland, Calif.: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Schiefer, G. and J. Deiters. 2013. Transparency for Sustainability in the Food Chain. Challenges and Research Needs. Oxford, England: Academic Press.

Schwab, K. 2016. “The Fourth Industrial Revolution.” The World Economic Forum, Geneva, Switzerland. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-what-it-means-and-how-to-respond/.

WBCSD. 2018. “Materiality in corporate reporting—a white paper focusing on the food and agriculture sector.” World Business Council for Sustainable Development, Geneva, Switzerland. wbcsd.org.

WEF. 2011. The Global Economic Burden of Non-communicable Diseases. The World Economic Forum and the Harvard School of Public Health. World Economic Forum, Geneva, Switzerland. weforum.org