Can Science Deliver Zero Hunger?

The UN’s 2030 target to curb food insecurity is fast approaching, and we’re losing ground. How can the global food system pull together to regain momentum?

Article Content

In the fall of 2015, world leaders convened at a United Nations summit in New York and made an audacious pledge: total eradication of hunger, worldwide, by 2030.

Under the auspices of five agencies, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), UNICEF, World Food Programme, World Health Organization (WHO), and International Fund for Agricultural Development, the initiative specified two fundamental goals: ensuring access to safe, nutritious, and sufficient food for all people, year-round; and eradicating all forms of malnutrition.

By almost any measure—quantified or qualified—the global food system is failing. Badly.

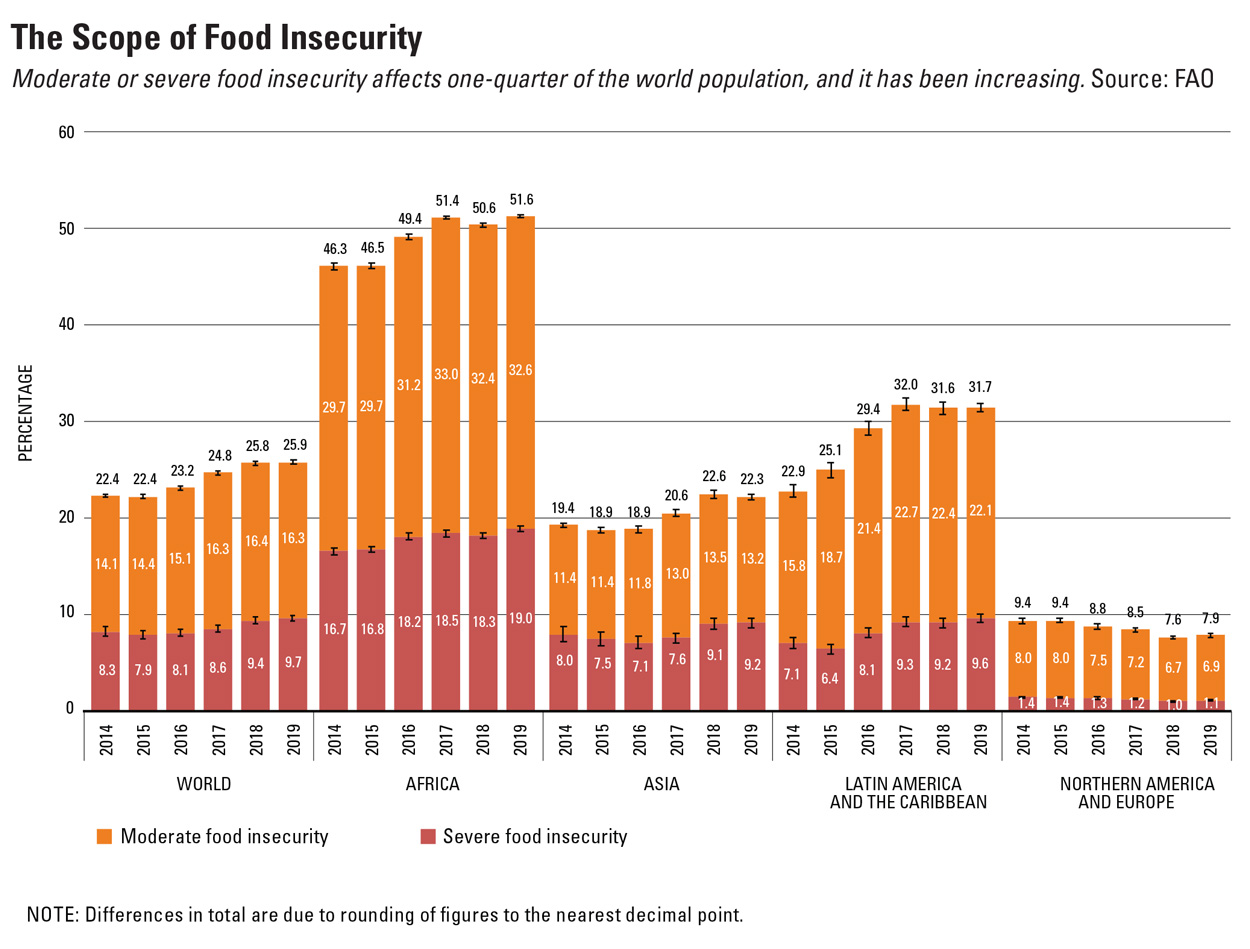

The numbers, cited in the UN’s 2020 report, The State of Food Security and Nutrition, are stark and sobering: An estimated 2 billion people, nearly 26% of the planet, have irregular, unreliable access to sufficient, nutritious food. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, almost 690 million people, or 8.9% of the global population, were chronically undernourished. Some estimates suggest that the pandemic added between 83 million and 132 million to that figure last year alone.

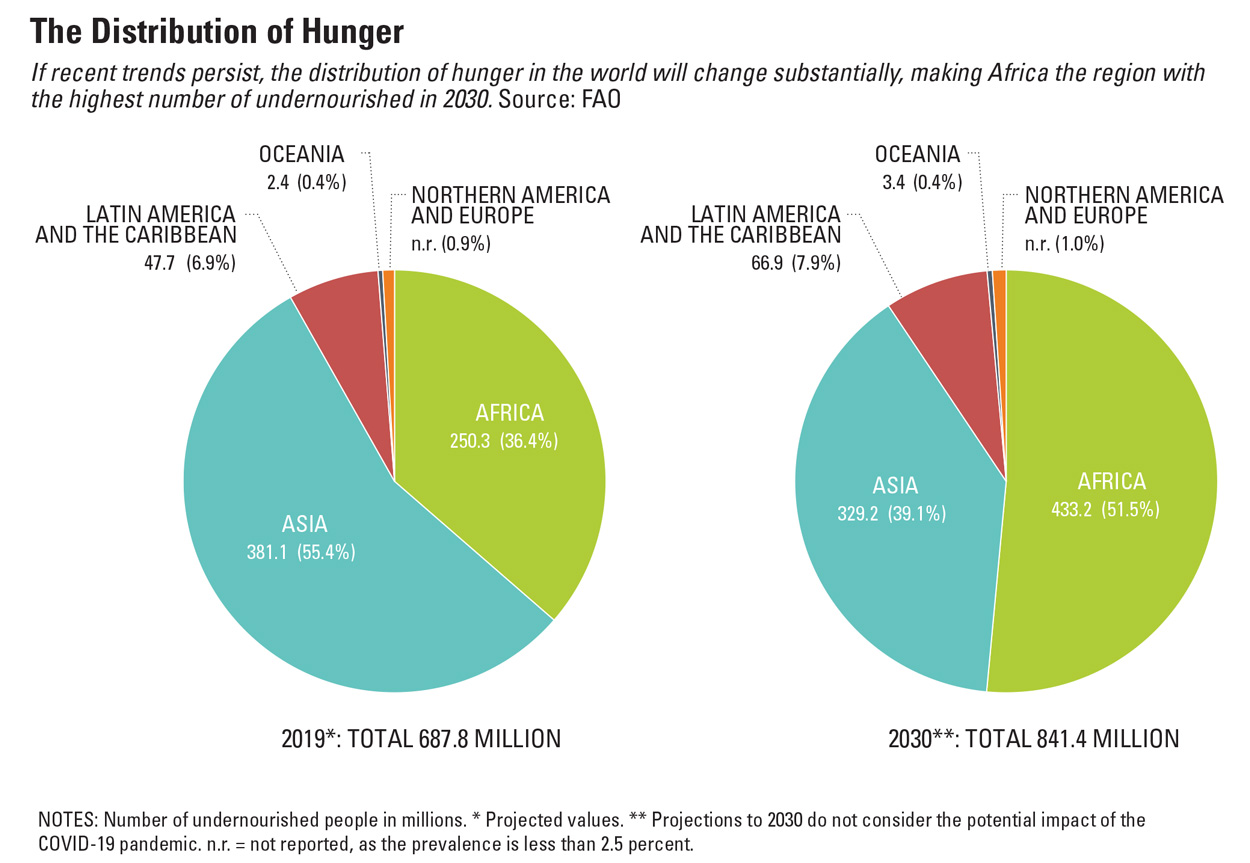

At its current pace, that count will reach 840 million by 2030.

Food insecurity and malnutrition disproportionately impact children. Despite a one-third improvement since 2000, an estimated 144 million children under the age of five in 2019 were stunted. An additional 47 million were wasted (see glossary, page 26). And 340 million suffered from micronutrient deficiencies. On the other end of the spectrum, lack of balanced nutritional access resulted in 38 million overweight children.

And while food insecurity is present throughout every corner of the world, any conversation inevitably arrives at the scope and severity of the crisis in Sub-Saharan Africa, where the prevalence of undernourishment (PoU) impacts 250 million people, or 19.1% of the population, more than twice the 8.9% global average. More troubling, if current rates persist, Africa’s PoU is slated to reach almost 26% by 2030, and at 433 million, would account for half the world’s hungry.

Although Asia currently accounts for more than half the global total, 381 million, that figure has actually improved by 8 million since 2015 and its large population translates to a PoU of 8.3%, slightly below the global average.

Latin America and the Caribbean are home to 48 million undernourished, 7.4% of the population; however, the region’s PoU is rapidly worsening, having increased by more than 9 million since 2015, and is projected to impact 9.5% of the population by 2030.

The urgency of regaining momentum toward 2030 goals has prompted a multilateral Food Systems Summit in September, adjacent to the UN General Assembly meeting in New York. And the topic plays a central role in IFT’s 2021 virtual event, FIRST (Food Improved by Research, Science, & Technology), July 19 to 21. In anticipation of the discussion, Food Technology canvassed a range of experts across the food system to offer insights on the opportunities and barriers to progress, as well as the role food science can play in solving a complex, multivariable problem, defined as much by economics, political science, and sociology as it is by agrology, nutrition, and microbiology.

Following are edited excerpts of their observations, analyses, and prescriptive responses to the essential question: “Zero hunger: Will we get there?”

In Search of Intersections

Adelia Bovell-Benjamin, professor of food and nutritional sciences at Tuskegee University and IFT Board Member, has worked around the world as a nutritionist, clinical dietitian, and food and nutrition consultant. Here, she urges the science of food community to pursue a more integrated, multidisciplinary approach.

From my point of view, one of the biggest things is to get infrastructure in place. I see these individual, small projects, but I don’t know how far this gets. And even if we look at the institutions doing projects, like the World Bank, you might have some change in the community, but it’s not systematic change. The infrastructure is just not in place to sustain the efforts.

I know there’s a very strong role for us as food scientists. But how do we integrate whatever we are doing into the system? I think that’s a big problem.

I was working in Sierra Leone doing dietary diversification. And right next to me ... you have another organization doing almost the same thing. The fragmentation causing duplication needs to be fixed.

As food scientists, we know what to do, but it has to be an integrated approach. In Tanzania, for example, they have loads of food. Agriculture is good. But what happens? They’re going to sell the food long before eating it. The kids would stay hungry because they are not going to eat the food, they’re going to sell the food. And they’re going to tell you, we are going to do that because we don’t want our children to struggle as hard as we are struggling. So, we are going to take that money from our crops, and we’re going to try to educate them.

We have to talk to social scientists, we have to look at cultural issues, we have to work with the sociologists. We can’t, as food scientists, just go in there and do “food scientist things.” We have to work with other [disciplines], and I don’t know if we have gotten to that point yet.

We need to integrate and not duplicate efforts. So, let’s say IFT wants to solve this food insecurity problem in the United States, for example. I’m saying we should have a big national team with sub teams in the various areas, with a range of expertise. So you would have your sociologist, you would have your ethicists, you would have your anthropologists, you would have your agriculture. That could make a difference.

We have to integrate the social, the cultural aspects. In Kenya, they had a famine. And the truckloads of food they [brought in] had yellow maize. Now, these people just don’t eat yellow maize. And even though they were starved, they would not eat the yellow maize because they eat the white maize. We have to be very aware of the cultural aspects of things.

Food scientists, by themselves, cannot solve this problem. We have to work with others.

Building Scalable, Interdependent Systems

Saint Louis–based physician Mark Manary is co-founder of Project Peanut Butter and a pioneer of RUTF (Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food) to treat severe malnourishment. Since 2004, Project Peanut Butter has treated more than 1 million children. Here, Manary advocates for practical, scalable food systems that embrace technology.

I’m a firm believer that we can feed this planet. But specialization is how the human race has survived and thrived on this planet. In Africa, we’re talking about a place where most people either raise their own food or a family member does it. And they process their food very locally, and everything’s very dependent on them.

And the result of that is, it works out in a survivable way most of the time. But when it doesn’t, it’s bad news. It’s suffering. And the kind of things that cause this to not work out are not really climate change, or wars, or things that we would consider as very extreme and huge. They’re … some animals have wrecked your garden; some pests have moved into the place where you grow food or store food; your family has become larger.

When we have plenty of food that’s being produced in a more efficient, mass production way, you can create some buffers. We have that capacity, but we’re going to have to have interdependence.

When you are treating a child for malnutrition, they’re at home, their mother’s been given a processed food, and she’s asked to feed the child every day. And they come back to clinic every couple of weeks, but the brunt of this work is happening with the mother at home. And we know that we can improve outcomes if the mother has what we call peer support.

So you say, “Wow, peer support, that’s great. How can we institutionalize that?” And so people come up with curriculums that have to do with knowledge impartation, telling them about what kind of foods are healthier, things like that. And those particular kinds of peer support don’t actually help the children recover any more. It’s not all about knowledge. It’s about applicable knowledge. It says, “In my community, in my neighborhood, I can go here and buy this, and that’s a good product. It’s good and nutritious for my kid.” Or, “When I cook it with this other food that we normally have, I modify it this way, and then that makes it better for my kid,” or something like that. Very local things.

I’ve talked about agriculture and eating, but there are a lot of steps in between there, and they all need to be in place and working. What I really feel is dangerous is the demonizing of technology in food processing, and in the food delivery chain. In order to feed more people, and with a greater rate of certainty, we need to install a modern supply chain and processing system that’s going to move crops.

And to feed the populations in Africa is going to require some movement of goods across borders, another thing that Africa just totally suffers. It would be like if every state in the United States had its own set of tariffs. This is the way it is with all these countries in Africa, 33% tariff. Really, I only want an operation big enough to deal with the needs in that country, because as soon as I take a box of it across the border, somebody says, “It has to be paid 33% tax.”

When I think about these next 30 years, I focus on Africa, because we’re talking about a population increase in the world of about roughly 2 billion people, and half of those people are going to be in Africa. This is everybody’s future. If we make that demographic shift go badly, we’re all going to suffer, whoever we are. Immigration, war, social disruption. And Africa [should be] one of the world’s bread baskets. The land is plentiful and fertile.

In Defense of Technology

Agrologist and consultant Robert Saik, founder and CEO, AGvisorPro, and author of Food 5.0: How We Feed the Future, and The Agriculture Manifesto, argues that scientific and economically viable solutions to sustainably scale agriculture production are too often overshadowed by political ideologies.

I have a pretty pragmatic view of this situation, having extensive background in plot physiology, solar chemistry, crop nutrition. I have shares in a farm in Uganda. I’ve done work in Uganda, Kenya, Nigeria, and Ukraine and Kazakhstan.

Can we feed 9 billion people? No question we can feed 9 billion people. However, ideologies are trumping science, and this is the major concern I have. We have to grow. You’ve heard these numbers: 10,000 years’ worth of food in the next 30 years. We have to increase food production 60% to 70% on every part of the planet. The pressure on the exporting nations is higher because we have to punch above our weight.

You have the European Union stating that they will demand that 25% of their production will be organic in the next number of years. Okay, so by any means, there’s going to be a yield drag [in the EU], between 8% to 12%. Where’s that food going to come from? Well, they’re going to put pressure on exporting nations like Brazil. It has one of the most diverse environments or ecologies in the world, and Brazil is going to be pressured to produce more.

I was participating in a three-day United Nations FAO Conference put on by the Committee for Global Food Security. I addressed two issues: One was food waste and the second was nutrient status of crops. Okay, so food waste ... everybody is concerned about scraping their plates at the restaurants in the garbage and what a waste that is. It’s nothing. The No. 1 food waste in the world is mycotoxins, by far. It’s the No. 1 destroyer of crops in field. It’s the No. 1 destroyer of crops in storage. You ever hear anybody talking about it? No. They’re going to talk about scraping off food from our plates into the garbage. We should stop that so much. That doesn’t mean anything. That’s not the big picture. Uganda is the No. 1 liver cancer area in the world. Why? Because of mycotoxins in food.

The second one is people say our food should be more nutrient-dense. I don’t argue with that point; however, if you test soils and your soil is zinc-deficient, your crops will be stunted, your livestock will be stunted, and your human beings will be stunted, permanently. I don’t care if you call it organic or agroecology, or regenerative, or whatever. If you don’t put more zinc into the soil from an outside source, you can’t increase the levels of zinc in the diet. End of story. It’s that simple.

Let’s get away from the discussion of ideology. If you ask people what does sustainability mean, they don’t know. If you ask them what does regenerative or agroecology mean, natural farming, they don’t know. They just throw these platitudes around.

What we need to have are discussions around agronomy and science and outcomes, rather than platitudes and ideologies. When you think about sustainability, I think about soil health, primarily organic matter. I think about water use efficiency, a critical metric. I think about greenhouse gas balance; I think that’s important. [But] everybody forgets about farm viability. If farmers aren’t surviving and if they’re struggling and they’re not thriving, how can they concentrate on sustainability?

Bridging Commerce and Science

Partners in Food Solutions (PFS) began 13 years ago as an internal volunteer initiative within General Mills. Today, the consortium includes General Mills, Cargill, DSM, Bühler, Hershey, Ardent Mills, and the J. M. Smucker Co., supporting food entrepreneurs across 11 African countries. Co-founders Jeff Dykstra and John Mendesh discuss the reciprocal value of leveraging corporate partnerships and the challenges facing local entrepreneurs.

Mendesh: Everybody has to play their part. Food science has an incredibly important role to play. It’s a gigantic role, but other players need to play their part as well.

I believe [food science] can do even more. And there are opportunities not completely understood. We’re very much focused on delivering nutrition. But it’s not nutrition unless they eat it. There’s a lot of other pieces that have to come into play. It might be to tell the story better … and by the way, I’m a scientist, so even attaching the word “science” requires us to undo certain things to take a step forward. And I come from big food as well, and we get accused of the things on the ingredient label [consumers] can’t pronounce. We may have overshot the mark a bit collectively as a community in unintended consequences by making it complicated.

Dykstra: We often say it’s better to be lucky than smart, because we just found this wide-open space where food scientists weren’t being leveraged to do their part. For a product developer at General Mills or Cargill to be able to take their 20 years of expertise and apply that with a small growing company in eastern Kenya, that wasn’t happening at any level of scale, prior to us.

Africa today imports something like $40 billion of food. It’s capable of growing, but there’s a lot of waste in the system. And ultimately, if we’re going to feed 9 billion people by 2050, Africa needs to become not only no longer importing, but a net exporter. And so if you think, what is the role of food science in that? We believe that food companies in the middle, just like here, are the entities that can take that raw crop and turn it into something that’s edible in some cases, or not perishable in others. And in some cases, add value to make it more nutritious. So it’s at the blocking and tackling level across Africa.

The companies we’re helping are industrial, they’re food companies. It’s not a romantic image of a farmer in a field or a child, but that’s where we can create impact. We believe that by helping that food company, all sorts of ancillary good is coming from that: You’re helping create demand for smallholder farmers; you’re helping provide local food that’s nutritious; you’re creating jobs; you’re building the economy.

You see in this space a lot of entities coming together, often public/private with very big intentions. And it’s announced to Davos, or there’s a press release, and you follow up on a lot of those one year, two years later, and it wasn’t that the intentions weren’t sincere, it just doesn’t go. I think what we did and were able to do right, and again, better lucky than smart, is that we spent three years really getting this right with one company, with General Mills. So by the time we started inviting new companies in, it was formed enough that we knew what we were inviting them into, but it was still wet enough cement that they could help shape it.

The companies signed on because they wanted to create an impact. There’s been a byproduct of value that has flowed back to them, the biggest by far through the lens of people development. Our 13-year existence has trended perfectly with employees wanting to be engaged in purposeful things at work. The byproduct was authentic employee engagement.

The lesson in that is, it can’t just be the cause, because CEOs are going to come and go, trends are going to shift. I think what we captured in this is very tangible soft value, in terms of recruiting, people development: 97% of our volunteers say they’re learning things at PFS that are applicable back to their day job.

This model works because we have these great corporate partners who happen to be based in the United States and Europe. But the future is on the ground in Africa. I think about the talent that’s developing across Africa and much of the developing world. There is still very much a paternalistic thinking that’s just not accurate. Some of our clients went to Wharton, worked at Goldman’s, worked for the governor of a big state in Nigeria. It’s not “poor Africans.” It’s really talented entrepreneurs who are getting stuff done in hard environments.

The vast majority of our clients are under-resourced. We learned pretty early on, we could bring world-class know-how, but if you didn’t have access to finance for that piece of $50,000 equipment that would triple your output, that $50,000 might as well be $50 million. And so we very intentionally in the last 10, 12 years have built up a number of partnerships with investors and the financial side. Everything from impact investors to local banks, equity funds, and really try to actively partner.

We started piloting the last few years, low-interest loans paired with grants on certain things like certification programs and labs that are going to improve food safety. And those are examples where the client is also putting some skin in the game. But that’s still almost as big a problem as it was 12, 13 years ago. Because it’s just really hard to efficiently and profitably get a loan of $100,000 into a high-risk ag food company that’s $800,000 in turnover. But absent that, they’re going to remain at $800,000 turnover. So that’s a tough one.

Turning Ag Waste Into Ag Wealth

Kamesh Ellajosyula, chief innovation and quality officer for Olam Food Ingredients in Bangalore, India, and Paul Nicholson, vice president, rice research and sustainability for Olam Global Agri in Singapore, discuss the need to deeply embed within communities and identify opportunities to cut waste and add value throughout the supply chain.

Ellajosyula: I think the community really needs to drive the understanding that the food on our plate is somebody else’s livelihood. And getting to that food on our plate has great impact on this planet of ours in terms of climate change. The choices we make, what we consume, how our dollar goes to work for the food that’s put on our plate, I think has tremendous impact. And if we can illumine the community, get them to understand this better, I think that itself would be the first step.

Nicholson: Let’s talk about fortification, because I think it’s a great example of where food science really answered a need. You need to meet the consumer where they are. In Africa and Asia, it is typical to wash rice, so a lot of the early fortification efforts actually weren’t getting the fortificants to the consumer; they were being washed off.

DSM and Olam came together with a solution: We actually extrude a kernel of rice. It’s actually a very short noodle. The dough for that noodle is embedded with fortificants: iron, zinc, and B vitamins. And then we can blend it into the rice, so it looks [exactly like] the rice the consumer expects. And the consumer experience after cooking it is identical to their experience of eating any other rice product. So we were able to take that technology into branded products in Ghana, under the Royal Aroma brand, which launched last year. And we were also able to take it into our third-party procurement, so it is in other brands around the world.

Ellajosyula: There’s so much that we can do to equip people, equip communities. We did a program in Niger and Ghana, where we trained farmers to grow bees. Now they can sell honey and bee wax. That allowed them to make $954 more per year. And when you think about per capita income in these parts of the world, this is really big money.

Another example is the cashew. When you look at the cashew tree, at the end of the cashew apple is the cashew nut. That’s all you use. The apples are just dropped; they’re left to rot away. These cashew apples are nutritious. So we brought a chef from Brazil into West Africa. And we got 30 women from the community, and she taught them various recipes, how do you blend apple juice and cashew and ginger or mango. So suddenly that one mango goes a lot further, because now they have got all those cashew apples from their own orchard, which they were throwing away and had zero value. They learned how to make cashew apple burgers and marmalades, which could be stored, because these apples rot away very quickly, but you can work that into a marmalade, then it’s good for many, many months.

We’ve been playing a fairly large role in coffee globally for many years. We’ve always seen that the coffee tree is a great biological asset. It produces the coffee fruit, but only the beans are used, and it’s really not utilized. You could make something like a cascara, which is the extract from the fruit, but it could be full of pesticides, it could be full of heavy metals, it could be contaminated with microbial problems.

But at the same time, research has shown there’s a lot of bioactive compounds in there: polyphenols, chlorogenic acid. And then people are beginning to show that this could help with obesity. A lot of different research is happening in the United States, in Canada, in parts of Europe.

But the question is, is it something you just feel good about doing research papers, or can you actually put it on a plate? So we spent time trying to figure out, how would you create cascara? How would you dry the cherry? How do you ensure the microbial counts stay low? How do you ensure that you do not get any sort of contamination? How do you train your farmers? How do you train the folks on the plantation? And how do you optimize post-processing?

We’ve been trying to address the role at the farmer level, user level, at the transformation, secondary, primary processing level, and also finally, ingredient innovation, and trying to do something exciting with it. It takes a completely holistic approach, end to end. And also recognizing, to begin with, there’s a lot of ag waste that is really waiting to be converted to ag wealth.

Food security is deeply connected to food waste. So the other big opportunity is finding ways to make sure food doesn’t get deliberately wasted. There’s so much that doesn’t get stored properly, gets wasted during post-harvesting losses, transportation, a whole bunch of other things.

That’s where food science and food technology can do a lot. The food industry could contribute tremendously to source better, make sure they’re sourcing sustainably. Make sure they understand the impact on communities where this is being sourced from. And consumers, therefore, have transparency. They can see through how their supply chain works, so they can choose to better invest their dollar. I think if some of this starts kicking in, I think the food industry and IFT can play a big role.