Understanding the Science Behind Chewing Gum

Wrigley is funding cutting-edge research by independent experts to explore the health benefits of chewing gum.

Innovation in the form of new product development and introduction has been faster than ever at Chicago-based Wm. Wrigley Jr. Co. In 2006, the company introduced 80 new products around the world, including Life Savers Gummies Fruit Splosions liquid-filled gums, as well as a variety of new, unusual chewing gum flavors like Mint Mojito and Raspberry Mint. These innovations came from Wrigley’s Global Innovation Center, a 150,000-sq-ft facility that opened in Chicago in 2005 and houses 250 scientists, packaging designers, technicians, marketers, and others who develop new confectionery products.

Wrigley also established the Wrigley Science Institute in 2005. This virtual organization is an entity separate from the company’s in-house research and development program. It was launched to generate ground-breaking science at major academic research facilities throughout the world on the potential health and lifestyle benefits of chewing gum—regardless of formulation. It is led by an executive director and supported by an advisory panel of experts who guide the organization’s work and its focus.

The inspiration for WSI was driven in large part by Wrigley’s consumers. Surinder Kumar, Wrigley’s Chief Innovation Officer, says that the company has been hearing from consumers for decades about chewing gum’s benefits. Some of them, he says, are “just plain common sense.” Through WSI, the company is exploring scientific proof behind the anecdotal evidence.

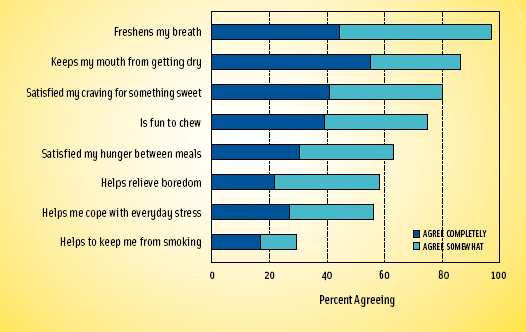

Consumer trend data from the 2005 NPD Group Snack Track shows that chewing gum is the number-one snack choice among adults age 18–54 in the United States. In an average week, more than half of Americans age 18–49 chew gum; the typical gum chewer consumes approximately 400 pieces a year. Not surprisingly, consumer trend data (Wrigley, 2003, 2005) indicate that the main reasons people chew gum are “to freshen breath,” “to enjoy the taste,” and for a “healthy mouth.” Yet, an increasing number of consumers view chewing gum as a means to help increase focus or concentration, reduce tension or stress, or manage caloric intake (Figure 1). Research has shown that chewing gum has a number of benefits in oral health, including removing food debris, neutralizing plaque acids, aiding in the remineralization of tooth enamel, and even helping reduce tooth decay. Several clinical trials demonstrate the benefits of chewing sugar-free gum on cavity reduction. For example, a long-term, two-year randomized, blind clinical trial was conducted in Budapest, Hungary, with 547 children age 8–13 years old at the start. The researchers concluded that the gum chewing resulted in a 39% decline in dental caries incidence compared to the non-chewing controls (Szoke et al., 2001).

Consumer trend data from the 2005 NPD Group Snack Track shows that chewing gum is the number-one snack choice among adults age 18–54 in the United States. In an average week, more than half of Americans age 18–49 chew gum; the typical gum chewer consumes approximately 400 pieces a year. Not surprisingly, consumer trend data (Wrigley, 2003, 2005) indicate that the main reasons people chew gum are “to freshen breath,” “to enjoy the taste,” and for a “healthy mouth.” Yet, an increasing number of consumers view chewing gum as a means to help increase focus or concentration, reduce tension or stress, or manage caloric intake (Figure 1). Research has shown that chewing gum has a number of benefits in oral health, including removing food debris, neutralizing plaque acids, aiding in the remineralization of tooth enamel, and even helping reduce tooth decay. Several clinical trials demonstrate the benefits of chewing sugar-free gum on cavity reduction. For example, a long-term, two-year randomized, blind clinical trial was conducted in Budapest, Hungary, with 547 children age 8–13 years old at the start. The researchers concluded that the gum chewing resulted in a 39% decline in dental caries incidence compared to the non-chewing controls (Szoke et al., 2001).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Wrigley’s past experience in the oral health research arena helped guide the establishment of WSI. The global advisory panel of renowned scientific experts (see sidebar on p. 26) is committed to supporting research related to the potential health and lifestyle benefits of chewing gum and to understanding what happens physiologically and psychologically when gum is chewed.

“Wrigley is making a significant long-term investment in research on the benefits of chewing gum, and we think the findings are going to be well worth the investment,” says Kumar, noting that WSI is a natural extension of Wrigley’s interest in innovation, which has been a part of the company’s culture since it was founded in 1891. “With WSI we wanted to make sure of two things,” he says. “First, that we had credible, highly competent researchers in the areas we are targeting and, second, that research was conducted under an independent banner.”

Benefits of Chewing Gum

Currently, WSI is funding research on the benefits of chewing gum in four primary areas: reducing situational stress; managing weight; increasing focus, alertness, and concentration; and improving oral health.

• Stress Relief. While stress is a fact of life, managing life’s smaller stresses may be helped by chewing gum. According to Wrigley studies (Wrigley, 2003, 2005), about 26% of teens and 15% of adults agree with the statement “when I am tense or excited, chewing gum helps calm me”; 24% of teens and 12% of adults report that chewing gum is a great way to vent when they are angry or frustrated; and 28% of teens and 15% of adults say that “chewing gum is a great way to help me feel more relaxed.”

--- PAGE BREAK ---

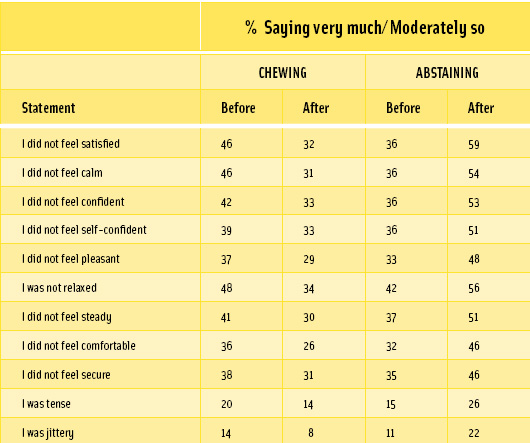

An online self-perception research study was conducted in 2006 to determine whether chewing gum can make gum chewers feel less stress/anxiety. Overall, this study (FRC, 2006) provides evidence that among heavy gum chewers—defined as those who chewed in the past week, chewed at least four days/week, and chewed 11 or more pieces/week—chewing gum reduces stress, while abstaining from chewing gum increases stress. More than half (56%) of the study participants agree with the statement “chewing gum helps me cope with everyday stress.” Everyday stress emotions such as not feeling satisfied, not feeling calm, and not feeling content increased when gum chewers abstained from chewing gum. Chewing gum appears to reduce the level of everyday stress emotions, resulting in greater feelings of “calm,” “satisfied,” “relaxed” (Table 1).

An online self-perception research study was conducted in 2006 to determine whether chewing gum can make gum chewers feel less stress/anxiety. Overall, this study (FRC, 2006) provides evidence that among heavy gum chewers—defined as those who chewed in the past week, chewed at least four days/week, and chewed 11 or more pieces/week—chewing gum reduces stress, while abstaining from chewing gum increases stress. More than half (56%) of the study participants agree with the statement “chewing gum helps me cope with everyday stress.” Everyday stress emotions such as not feeling satisfied, not feeling calm, and not feeling content increased when gum chewers abstained from chewing gum. Chewing gum appears to reduce the level of everyday stress emotions, resulting in greater feelings of “calm,” “satisfied,” “relaxed” (Table 1).

• Weight Management. Trading a stick of chewing gum at about 5–10 calories for a typical snack like a couple of chocolate chip cookies containing 140 calories can save more than 130 calories. Consumers, it seems, intuitively know this, and stories are common about the use of chewing gum as a low-calorie diversion that helps limit snacking.

On the research front, a study conducted at the Mayo Clinic found that mastication can burn approximately 11 calories/hr, a boost of about 19% over a baseline resting expenditure level (Levine et al., 1999). Heatherington and Boyland (2007) showed that chewing gum before snacking can help reduce hunger, diminish cravings for sweets, and decrease snack intake by 36 calories. The 60-person study of healthy men and women age 18–40 tested the effects of chewing gum on post-lunch appetite and snacking. The researchers suggest that gum chewing suppressed appetite, specifically for sweets, and reduced snack intake overall.

• Focus, Alertness, and Concentration. Since World War I, the U.S. military has supplied chewing gum in field combat rations. Athletes and coaches are often seen chewing gum on the playing field. And perhaps most intriguingly, some school teachers are reversing traditional policies against chewing gum by encouraging students to chew gum during tests to help heighten alertness and concentration.

Research in the area of chewing gum and cognitive performance is complex, but results are emerging on a number of fronts. Psychological research was conducted at the University of Northumbria, England, with 75 young adults age 24–26 assigned to one of three groups; one group chewed gum during 20 minutes of memory and attention tests, a second group mimicked chewing movements without gum, and the control group did not chew. Tests included questions requiring short-term memory, such as recalling words and pictures, plus “working memory” used to recall a telephone number, for example. Researchers found that chewing gum enhanced working and long-term memory. Gum chewers scored significantly higher on immediate word recall and on delayed word recall than the control group (Wilkinson et al., 2002).

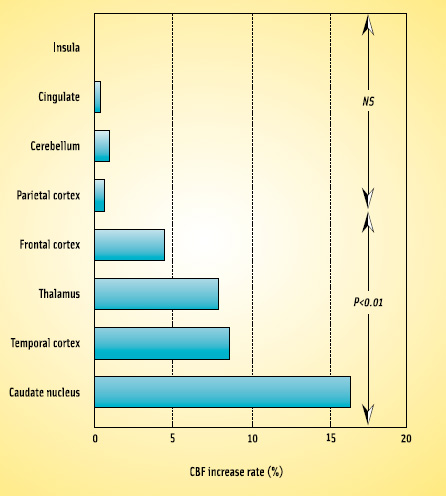

A study conducted in Japan showed that blood flow to the brain increased by 25% when chewing gum (Sasaki, 2001). How and why this has an impact on physiological as well as psychological behavior is still to be determined, but this observation provides a plausible mechanism to explain the apparent effect of chewing gum on cognitive functions and stress reduction. This is an exciting area for future research (Figure 2).

A study conducted in Japan showed that blood flow to the brain increased by 25% when chewing gum (Sasaki, 2001). How and why this has an impact on physiological as well as psychological behavior is still to be determined, but this observation provides a plausible mechanism to explain the apparent effect of chewing gum on cognitive functions and stress reduction. This is an exciting area for future research (Figure 2).

--- PAGE BREAK ---

• Oral Health. Substantive research supports chewing gum’s positive effect on oral health, largely the result of chewing gum’s saliva-producing effect. When we eat, fermentable carbohydrates are broken down in the mouth by salivary amylase and utilized by the plaque bacteria as food, with organic acids formed as the breakdown products. These acids lower the pH of the mouth, making it more acidic. When the oral pH level drops below 5.5–5.7, the acids from the bacterial fermentation begin to dissolve the minerals from the tooth surface. During the course of eating, as minerals from the teeth dissolve, lesions are created in the enamel of teeth, beginning the decaying process. Early lesions are reversible. If left unchecked, however, these lesions can weaken the tooth surface, leading to dental caries (Edgar et al., 2004).

Chewing gum stimulates increased saliva flow in the mouth, thereby accelerating the clearance of food debris and dietary carbohydrates and decreasing the risk of caries development (Richardson and Castalki, 1965). Furthermore, bathing teeth in saliva that is not acidic can actually help to remineralize the teeth, building back mineral density in the teeth to reverse lesions and add strength (Manning and Edgar, 1993).

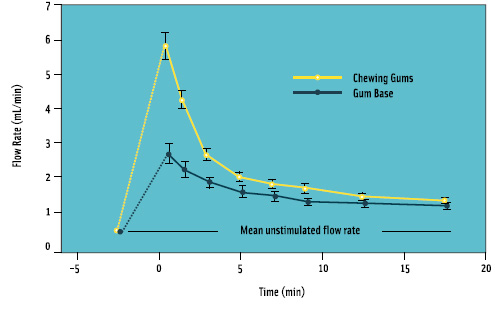

Chewing gum increases saliva production via gustatory stimulation and the mechanical action of chewing (Figure 3). Together, these actions accelerate salivary flow rate by about 10-fold (Edgar et al., 2004), demonstrating that chewing gum can be an important defense mechanism against dental caries and a positive influence on oral hygiene.

Chewing gum increases saliva production via gustatory stimulation and the mechanical action of chewing (Figure 3). Together, these actions accelerate salivary flow rate by about 10-fold (Edgar et al., 2004), demonstrating that chewing gum can be an important defense mechanism against dental caries and a positive influence on oral hygiene.

Furthermore, recent research suggests that oral health—having a “healthy mouth”—is important beyond caries reduction and may play a pivotal role in overall health. For example, periodontal disease, an indicator of poor oral hygiene, is associated with greater risk of diabetes, atherosclerosis, and pregnancy complications (Kosden, 2006).

Research in Progress

At present, WSI has 16 studies in various stages of progress and continues to pursue additional research. While funding for these studies is provided by Wrigley, the research itself will be published by the researchers in peer-reviewed journals.

“In some cases there will be strong research and strong support for the benefits,” notes Kumar, “and in other cases, we may find other results. That is the point of conducting independent research like this—to learn and determine scientifically supportable benefits of chewing gum.”

The “newness” of this kind of work has created some challenges. Researchers have encountered some interesting but unexpected hurdles while developing protocols to study the physiological and psychological impact of chewing gum. In China, for example, a study exploring the link between chewing gum and concentration took an unusual twist when students who were not accustomed to chewing gum seemed to concentrate more on the act of chewing the gum rather than on their assigned task. Other studies are underway with subjects more familiar with the habit of chewing gum.

As the science emerges, the results of the studies will be communicated to consumers and scientific and professional communities. The learnings from WSI-sponsored studies may also provide insights to the company’s R&D functions for development of enhanced chewing gum formulations. For instance, if it’s determined that chewing gum improves cognition or reduces stress, Kumar says, that might lead to the investigation of products containing natural or herbal extracts that can further improve cognition or reduce stress.

No matter the outcomes of the research supported by WSI, its findings will help Wrigley better understand its products and their potential impact on the lives of consumers.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

CHEWING GUM

Chewing gum can be traced back to the ancient Greeks who chewed “mastic” gum, made from the resin of the mastic tree. Ancient Mayans chewed chicle from the sapondilla tree that grows in the tropical rain forests of Central America, and American Indians chewed resin made from the sap of spruce trees. Modern chewing gum was first developed in the U.S. in the 1860s.

Today’s chewing gums are made from gum base, softeners that give it the appropriate chewing texture, sweeteners, and flavorings, which provide sensations like cool mint or spicy cinnamon. Today’s synthetic gum base materials are used to provide consistent quality and more variety in producing new kinds of gums. Glycerin and other vegetable oil products help to blend the ingredients and keep the gum soft and flexible by retaining the proper amount of moisture.

Sweeteners in traditional chewing gum include cane sugar, beet sugar, and corn syrup. Sweeteners in sugar-free gum include mannitol, xylitol, sorbitol, and/or aspartame. The most popular flavors for chewing gum in the U.S. are obtained from mint plants, which are carefully cultivated for delicate, lasting flavor. A variety of fruit and spice essences also provide flavoring.

WSI ADVISORY PANEL

The activities of the Wrigley Science Institute are guided by the Executive Director of the Institute, Gilbert A. Leveille, Ph.D., Sc.D., and by an international advisory panel of respected, independent experts in each of the institute’s priority areas—diet and weight management; stress; focus, alertness, and concentration; and oral health. Panel members include researchers from the United States, United Kingdom, and China.

• Molly Gee, M.Ed., R.D., Project Leader, Look Ahead study, Baylor College, Houston, Tex.

• Robert Genco, D.D.S., Ph.D., Distinguished Professor of Oral Biology and Microbiology and Vice Provost, State University of New York at Buffalo.

• Marion Hetherington, D.Phil., Professor of Biopsychology and Chair of the Psychology Dept., Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow, Scotland.

• James Hill, Ph.D., Professor of Pediatrics and Medicine, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver.

• Stephen Moss, D.D.S., Professor Emeritus, College of Dentistry, New York University, New York City.

• Andrew Scholey, Ph.D., Professor of Psychology and Founder and Director of the Human Cognitive Neuroscience Unit, University of Northumbria, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England.

• Andy Smith, Ph.D., Professor of Psychology and Director of the Centre for Occupational and Health Psychology, Cardiff University, Cardiff, Wales.

• Thomas Wadden, Ph.D., Professor of Psychiatry and Director, Weight and Eating Disorders Program, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia.

• Houcan Zhang, Professor of Psychology and member of the University Administration Board, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China.

• Xiaolin Zhou, Ph.D., Professor of Psychology and Director, Center for Brain and Cognitive Sciences, Beijing University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China.

by Gilbert A. Leveille, Ph.D., Sc.D., a Fellow and Past President of IFT, is Executive Director, Wrigley Science Institute, Wrigley Global Innovation Center, 1132 W. Blackhawk St., Chicago, IL 60622 ([email protected]).

References

Dawes, C. and Dong, C. 1995. The flow rate and electrolyte composition of whole saliva elicited by the use of sucrose-containing and sugar-free chewing gums. Arch. Oral Biol. 40: 669-705.

Edgar, M., Dawes, C., and O’Mullane, D. 2004. “Saliva and Oral Health,” 3rd ed. Brit. Dental Assn., London.

FRC. 2006. The impact of chewing gum on consumers’ stress levels. FRC Research Corp., New York.

Heatherington, M.M. and Boyland, E. 2007. Short-term effects of chewing gum on snack intake and appetite. Appetite 48: 397-401.

Kosden, L.A. 2006. The oral-systemic health connection: An update for the practicing dentist. J. Am. Dental Assn. 137: 1S-36S.

Levine, J., Baukol, P., and Pavlidis, I. 1999. The energy expended in chewing gum. New Eng. J. Med. 341: 2100.

Manning, R.H. and Edgar, W.M. 1993. pH changes in plaque after eating snacks and meals and their modifications by chewing sugared or sugar-free gum. Brit. Dental J. 174: 241-244.

Richardson, A.S. and Castalki, C.R. 1965. Current status of chewing gum in preventative dentistry. J. Can. Dental Assn. 31: 185-191.

Sasaki, A. 2001. Influence of mastication on the amount of hemoglobin in human brain tissues. J. Stomatological Soc. 68(1): 72-81.

Sesay, M., Tanaka, A., Ueno, Y., Lecaaroz, P., and Beaufort, D. 2000. Assessment of regional blood flow by xenon-enhanced computed tomography during mastication in humans. Keio J. Med. (Feb. Suppl.) 1: A125-A128.

Szoke, J., Banoczy, J., and Proskin, H.M. 2001. Efficacy of after-meal sucrose-free gum-chewing on clinical caries. J. Dental Res. 80: 1725-1729.

Wilkinson, L., Scholey, A., and Wesnes, K. 2002. Chewing gum selectively improves aspects of memory in healthy volunteers. Appetite 38: 235-236.

Wrigley. 2003. Wrigley chewing gum usage and purchase study. Wm. Wrigley Jr. Co., Chicago.

Wrigley. 2005. Wrigley chewing gum usage and purchase study. Wm. Wrigley Jr. Co., Chicago.