Shattering The 'Healthy' Food Myth

Understanding that behavior—and not food—is to blame for the fact that so many Americans are overweight and obese sheds light on the need for a new approach to product development.

It is a basic charge of the food industry to ensure all foods are safe and nutritious. In contrast, when looking at health and wellness, obesity is rising globally. If the food we have made available to the world is safe and nutritious, then why is obesity on the rise and wellness in decline? Many in and outside the food industry adhere to the belief that simply making food more “healthy” will solve wellness problems such as obesity. This article exposes this belief as a myth and proposes bold new thinking for how the food industry can make a positive impact in addressing this global problem.

Food is not the culprit; it is consumer behavior. In the United States and other developed countries, there is not a lack of low-cost, safe, or nutritious food. Yet regardless of availability, the fact remains that food is often over-consumed and over-indulged. The rise in obesity has been associated with increasing portion size since the 1970s (Young and Nestle, 2002). Portion size has been cited as a chief contributor to obesity through over-consumption and the over-indulgence of foods with high caloric density (Ello-Martin, 2005; Shelke, 2010). It is not simply food choice behavior that contributes to lack of wellness. Lifestyle choices are also a factor. The 2011 Food & Health Survey (IFIC, 2011) found 43% of Americans claiming a sedentary lifestyle, an increase since 2010. Lifestyle impacts how and why consumers choose to use food and the moments within which food is consumed.

When these lifestyle-driven behaviors of over-consumption and over-indulgence become habitual, they often lead to poor health conditions contributing to billions of dollars in ballooning healthcare costs. For these reasons, the food industry is experiencing increased pressure from government regulation such as new labeling requirements. Food consumption education spending is also on the increase. The U.S. Dept. of Agriculture alone spends a billion dollars a year on childhood nutrition education (Mendoza, 2007). However, it is going to take much more than regulation and education to turn the wellness tide. In fact, ripples of consumer change exist today that—when listened to—provide food companies with a roadmap to a wellness solution. This roadmap will not only address the public health challenge facing America (such as wellness), but will provide new competitive advantages for food companies.

This wellness solution applies a new lens from which to focus innovation. Instead of viewing innovation efforts through the lens of the product, where the focus is on changing the qualities of food to be “healthier,” this approach shifts the focus through the lens of behavior. Here, the question becomes, “How can food be designed and developed to change consumer behavior?”

--- PAGE BREAK ---

The Importance of Wellness Behavior

Behavioral psychology is rapidly unlocking our understanding of how cognitive processes motivate consumer behavior. What has emerged from this field is the startling realization that as much as 95% of all consumer behavior is habitual in nature, driven by our unconscious perceptions (Martin, 2008). Sensory perceptions, such as cues in the form of imagery, words, sounds, smells, and other stimuli are sensed from the environment, triggering unconscious desires to possess and consume.

This has profound implications for product innovation pertaining to wellness. Consider the fact that taste continues to be cited as the most important driver of food selection (Sloan, 2012) for 87% of consumers (IFIC, 2011). This has contributed to the myth that wellness problems, such as obesity, can be solved by improving the taste of more healthy foods. This is simply not true. In the same study, taste was cited by only 5% of people as a reason why they don’t select healthier foods. For those trying to lose weight, only 12% cited poor taste as a barrier to their weight loss (IFIC, 2011). This means that while taste is an important behavior driver, making great-tasting foods alone will not change behaviors toward wellness. In order to move consumers toward wellness, the product innovation focus must shift from fulfilling hedonics to motivating behavior. Product design must focus on identifying cues that create anticipation for a specific behavior, and development must focus on identifying cues that signal the fulfillment of that behavior.

Behavior-Driven Innovation

Innovation is the basis by which food companies respond to consumer change. It can also impact consumer change by providing consumers with the choices they seek. Understanding what consumers seek and responding through innovation to their concerns and wants is the root of a bold new approach to innovation—behavior-driven innovation (Lundahl, 2012). Behavior-driven innovation is rooted in the field of behavioral psychology. It offers new possibilities to solve the wellness problem through food product innovation.

Understanding the underlying drivers of behavior—within the appropriate situational context— leads to a very different framework for product innovation and development. This blurs the line between food science and marketing science to achieve product success. Cues form the basis for a new way to design and develop new products such that they deliver against the drivers of behavior within targeted moments of life. Otherwise, product design occurs in a behavioral vacuum. For this reason, a behavior-driven approach shifts the innovation process to focus on behavior.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

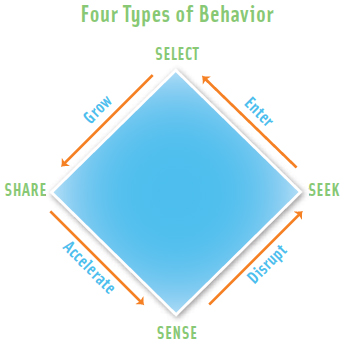

There are four basic types of behavior associated with all food and beverage products (Figure 1). These include sensing, seeking, selecting, and sharing. Sensing behaviors are habits motivated by sensed cues in the environment of behavioral moments. Seeking occurs when consumer habits have been disrupted. Disruption is the first step in the process for forming new behaviors. It occurs when consumers face situations where the stakes or consequences are high or when faced with new information that creates uncertainty in the outcome. In these moments, autopilot of the unconscious mind gives way to conscious seeking and rational decision making. Selecting behavior is motivated by designing concepts (i.e., packaging and positioning) that create anticipation that the product will fulfill what consumers seek. The outcome of product usage is the association of new cues that signal how well a product delivers against anticipated experiences. Reinforcing these associations results in new habits.

There are four basic types of behavior associated with all food and beverage products (Figure 1). These include sensing, seeking, selecting, and sharing. Sensing behaviors are habits motivated by sensed cues in the environment of behavioral moments. Seeking occurs when consumer habits have been disrupted. Disruption is the first step in the process for forming new behaviors. It occurs when consumers face situations where the stakes or consequences are high or when faced with new information that creates uncertainty in the outcome. In these moments, autopilot of the unconscious mind gives way to conscious seeking and rational decision making. Selecting behavior is motivated by designing concepts (i.e., packaging and positioning) that create anticipation that the product will fulfill what consumers seek. The outcome of product usage is the association of new cues that signal how well a product delivers against anticipated experiences. Reinforcing these associations results in new habits.

A behavior-driven approach to innovation puts the focus of product development on delivering cues that signal fulfillment of behavior drivers across a collection of moments—appealing to the unconscious mind. This requires food innovators to look beyond the physical product and consider the entire experience within which the product provides meaning. The social context and social interaction with products is rapidly changing. Sharing behavior is fundamentally changing how consumers learn of new products and, in turn, increases their motivation to try.

A good example is Chobani Greek Yogurt. It has taken the market by storm, quickly becoming the No.1-selling yogurt (10% market share) and growing sales from zero to $700 million in just four years. The more dense protein of the yogurt cues appetite suppression and its promise for more sustaining energy. Yet the more amazing fact is that this product achieved its success while spending only $200,000 on advertising during 2009 and 2010, focusing efforts primarily on social media (Elliott, 2011; Steiner, 2011). In other words, consumer sharing behavior, enabled by social media network effects, accelerated the adoption of Chobani Greek Yogurt, allowing it to become the category leader.

This behavior-driven approach to innovation opens up new vistas for companies seeking growth platforms that combat the trends in obesity to improve wellness. It does this by identifying cues that deliver against behavior drivers, validating that the final product indeed delivers relevant behavioral change. This is a fundamental change in how marketing and sensory research inspires and guides product development.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Wellness as a Behavior Driver

Evidence is building that wellness is a lead driver of consumer behavior. This behavior is expressed not only by what consumers are buying, but by what they are seeking and sharing. For example, consumers are flooding social media networks with their demands. Social media empowers consumers, providing them with the means to more broadly express their opinions. As a result, consumers use social media to seek brands that work for them. In turn, they share their support of these brands when discovered.

A recent study on consumer meal-replacement behaviors applied social media research to listen to consumer demands and to uncover moments where meal-replacement behavior occurs (InsightsNow, 2011). This study used the information gathered from social media research to design a survey of 3,000 consumers within the U.S. general population. This study found wellness-related goals (e.g., to lose weight); attitudes (e.g., about brands, companies, and choices); beliefs (i.e., what one should or should not do); and ideals to characterize meal-replacement moments in a variety of situations (e.g., replacing a normal dinner). Based on the study, meal-replacement moments are also characterized by behavior-drivers (e.g., curb my appetite, keep my energy up, fit into my busy schedule) that impact what consumers seek or desire and what they actually choose to consume.

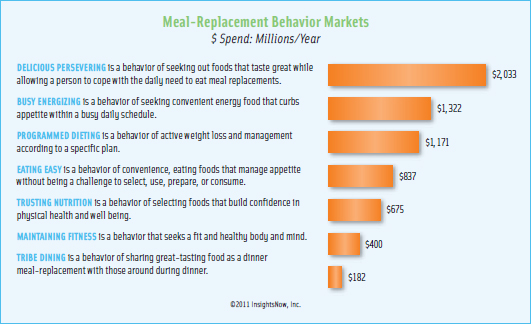

The study on meal replacement uncovered seven “behavior markets,” which are defined as collections of moments that share similar behavior drivers (Figure 2). One behavior market is Programmed Dieting. Programmed Dieting moments are characterized by choices to achieve active weight loss by replacing normal breakfast, lunch, and dinner meals when at home. This behavior is exhibited by 23% of people who replace meals and occurs on average 17 times a month. It is interesting to note that nearly a third (32%) of the consumers in these moments are not selecting products habitually, i.e., not using a set programmed diet plan. Programmed Dieting represents a nearly $1.2 billion behavioral market against which food companies can target by designing products with new cues that signal the promise of weight loss.

The study on meal replacement uncovered seven “behavior markets,” which are defined as collections of moments that share similar behavior drivers (Figure 2). One behavior market is Programmed Dieting. Programmed Dieting moments are characterized by choices to achieve active weight loss by replacing normal breakfast, lunch, and dinner meals when at home. This behavior is exhibited by 23% of people who replace meals and occurs on average 17 times a month. It is interesting to note that nearly a third (32%) of the consumers in these moments are not selecting products habitually, i.e., not using a set programmed diet plan. Programmed Dieting represents a nearly $1.2 billion behavioral market against which food companies can target by designing products with new cues that signal the promise of weight loss.

Programmed Dieting sits in stark contrast to the Eating Easy behavior market, whose moments are characterized by the drivers of convenience and appetite management while outside the home or at non-typical meal times. Easy Eating accounts for $800 million in spending, with 48% of consumption behavior explained by consumers seeking meal-replacement products. Products consumed in these moments include energy bars, drinks, fruit, sandwiches, cereals, and snack foods like chips. Potential innovation in this market should proceed by offering alternatives with cues that signal the promise of convenience and appetite suppression.

By focusing product development on wellness-related behavior drivers, products will better fulfill consumer desires across relevant moments of product choice and usage.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Innovating Wellness

Taking a behavior-driven approach to solving the wellness challenges facing the U.S. population requires the formation of a new innovation process.

Step 1. Shatter the “healthy” food myth. The intent of this article and the first step in solving wellness problems such as obesity is to reject the belief that the problem is food. It makes business sense to focus innovation on wellness behavior. Goals to change wellness behavior align more with what consumers seek. This creates more possibilities for success than goals focused strictly on making food healthier.

Step 2. Target wellness behavior markets.

Start the innovation process by listening for the moments in which wellness is influencing or could influence product choice. Define the markets by aggregating moments together that share the same behavior drivers. Identify opportunities within those markets where consumers are disrupted and seeking wellness-driven product alternatives or where habits can be disrupted by the introduction of products that better fulfill wellness-related behavior drivers.

Step 3. Inspire and guide wellness products.

Focus design and development of wellness products on targeted behavior drivers. Design cues into concepts that create the anticipation that the product will fulfill behavior drivers. Deliver product experiences that reinforce that the desired wellness outcomes will be achieved.

Step 4. Validate wellness impact. Measure wellness impact based on how well new products deliver against targeted behavior drivers. Apply these measures to improve decision making.

Final Thoughts

It is a myth that food is the culprit of obesity and unhealthiness. Wellness problems can only be solved by changing consumer behavior. This behavior change cannot be realized simply through education, regulation, or optimizing healthy foods for taste preferences. It requires changing the focus of innovation to ensure products achieve behavior change.

Behavior-driven innovation is a new path for the food industry to achieve this broader mission—to help consumers achieve wellness. This requires a fundamental shift in how the industry goes about food innovation. This approach focuses food innovation on understanding the true drivers that motivate wellness behavior. It applies behavioral psychology to better design products against behavior drivers. It focuses on building cues into food products that align and signal with what consumers desire—to achieve wellness.

Focusing on behavior change through innovation is not only the best way to reduce obesity and unhealthy food consumption, it makes business sense. This approach creates new vistas for companies to achieve sustained growth through the introduction of products that offer new ways for consumers to achieve wellness.

Dave Lundahl, Ph.D., a Professional Member of IFT, is President and Chief Executive Officer, InsightsNow Inc., 1600 SW Western Blvd., Suite 350, Corvallis, OR 97333 ([email protected] and twitter/com/DaveLundahl).

Greg Stucky, a Professional Member of IFT, is Chief Research Officer, InsightsNow Inc. ([email protected]).

Content from “Shattering the ‘Healthy’ Food Myth” will be the general focus of Dave Lundahl’s co-presentation at IFT’s Wellness 12 conference, March 28-29, 2012. Additional discussions on this topic can be found at www.behaviorlens.com/blog.

References

Elliott, S. 2011. Chobani, Greek yogurt leader, lets its fans tell the story. New York Times, February 16.

Ello-Martin, J. A., Ledikwe, J.H., and Rolls, B.J. 2005. The influence of food portion size and energy density on energy intake: implications for weight management. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 82(supplement): 236S– 41S.

IFIC. 2011. 2011 Food & Health Survey. International Food Information Council Foundation, Washington, D.C. www.foodinsight.org.

InsightsNow. 2011. Meal-Replacement Research Study. Corvallis, Ore. www.insightsnow.com.

Lundahl, D.S. 2012. Breakthrough food product innovation through emotions research. Elsevier Inc., London.

Martin, N. 2008. Habit: The 95% of behavior marketers ignore. FT Press, Upper Saddle River, N.J.

Medoza, M. 2007. AP: Nutrition education ineffective. USA Today, July 4.

Shelke, K. 2010. Formulating wellness foods with behavior change in mind. Paper 276-02, presented at Ann. Mtg., Inst. of Food Technologists, Chicago, Ill., July 17-20.

Sloan, A.E. 2012. What, when, and where America Eats, Food Technol. 66(1): 20-32.

Steiner, C. 2011. The $700 million yogurt startup. Forbes, September 8.

Young, L.R. and Nestle, M. 2002. The contribution of expanding portion sizes to the obesity epidemic. Am. J. Public Health 92(2): 246-249.