Laser pinpoints salmonella; Oil-free emulsions

CUTTING EDGE TECHNOLOGY

Laser pinpoints Salmonella

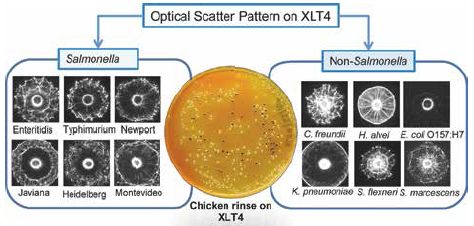

Purdue University researchers have developed a laser sensor that can identify Salmonella bacteria grown from food samples about three times faster than conventional detection methods. Known as BARDOT (pronounced bar-DOH), the machine uses a laser beam to scan bacteria colonies and generate a distinct black and white "fingerprint" by which they can be identified. BARDOT takes less than 24 hrs to pinpoint Salmonella.

"BARDOT allows us to detect Salmonella much earlier and more easily than current methods," said Arun Bhunia, Professor of Food Science, who created the machine with then- Purdue Engineer Daniel Hirleman.

Current Salmonella detection methods can take 72 hrs to yield results and often require artificial alteration of the bacteria colonies. The BARDOT system identifies bacteria colonies by using light to illuminate their natural characteristics, preserving the colonies for later study. The machine can be operated with minimal training and used in locations with limited resources, Bhunia said.

BARDOT, short for "bacterial rapid detection using optical scatter technology," uses a red diode laser to scan bacteria colonies on an agar plate. When the light penetrates a colony, it produces a scatter pattern, a unique array of rings and spokes that resembles the iris of an eye. The pattern is matched against a library of images to identify the type of bacteria.

To test BARDOT's ability to identify Salmonella, Bhunia and his fellow researchers grew bacteria from rinses of contaminated chicken, spinach, and peanut butter on agar plates for about 16 hrs. After the plates were covered with tiny spherical colonies of bacteria, they placed each plate inside the instrument and scanned the colonies.

BARDOT identified Salmonella bacteria with an accuracy of 95.9%. It also individually distinguished eight of the most prevalent Salmonella serovars. Identifying a particular serovar helps trace bacteria to the original source of contamination.

Atul Singh, postdoctoral research associate, said BARDOT could be an effective preliminary screening tool, especially for food processors testing a large number of samples. "BARDOT screens quickly and inexpensively," he said. "If you get a positive result for Salmonella, you can do a follow-up test. This can help food processors make more informed decisions."

Oil-free emulsions for low-fat foods

Technology from NIZO food research and 12 academic and industrial partners has produced emulsions consisting of water-soluble ingredients instead of oil and water. The group, led by Hans Tromp, NIZO food researcher and lecturer in applied colloid chemistry at the Dutch University of Utrecht, has applied protein-polysaccharide combinations to create the same texture as oil-based emulsions. Finding the right food-grade emulsifiers will enable their application in foods.

Emulsions of water-soluble ingredients offer the possibility to simulate the experience of fat with low-caloric substitutes. Water-water emulsions have certain characteristics that make them suitable for use as substitutes for oil-water emulsions. By applying such emulsions, products may be created that contain less fat, but generate a creamy mouthfeel.

Finding the right emulsifiers is key to the new emulsions. In water-water emulsions, the surface tension at the interface is many times smaller than that in oil-water emulsions. The surface tension is the factor responsible for instability, and hence the mouthfeel of emulsions. During consumption, an emulsion must destabilize to form a film of oil or fat covering part of the surface of the tongue. This creates the experience of creaminess that consumers tend to appreciate. Thus, emulsifiers serve not only as stabilizers, but also as means for manipulating stability.

"An emulsion consisting of gelatin and a polysaccharide whose gelatin-rich emulsion droplets have been gelled to make them stable could be used to replace a portion or all of the fat or oil globules in emulsions such as mayonnaise, cream, or dressings," explained Tromp. "The next step is to test this in foods."

If you are working on or know of some cutting edge technology that you would like to be featured in this column, please send an email to [email protected].