Eastern Influence

CONSUMER TRENDS

Without a doubt, the Far East has had the most dramatic effect on American culinary, restaurant dining, and in-home eating trends in recent years and will continue to do so for generations to come.

According to a DLG Research survey for Restaurant Business last year, 40% of high school students were planning to try Vietnamese foods, 40% Thai, 38% sushi, 31% Japanese, and 5% even more exotic Chinese dishes. Asian Americans, the second fastest-growing population segment, have kept their preference for native foods and ingredients, upscaling restaurant options and broadening traditional supermarket offerings. And top chefs confirm that Far Eastern techniques are quickly becoming the norm for formal culinary training.

According to Taylor Nelson Sofres, next to American and Italian cuisines, consumers enjoy “Chinese” most, ranking it four points higher than Mexican and three below Italian fare. Chinese, the third most popular restaurant cuisine, was purchased by 59% of consumers during the past six months. Japanese (18%) and Thai (11%) also made the “top six” list. Sales of Panda Express hit $228 million, and P.F. Chang (340 units, $153 million) opened its Pei Wei Asian Diners, new quick-service Asian eateries.

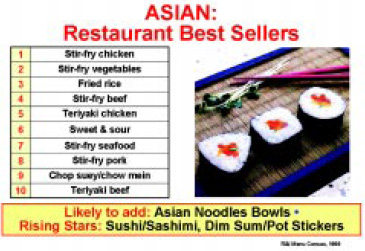

Asian flavors, entrees, and cooking techniques have become commonplace on American menus. According to the latest Restaurant & Institutions Menu Census, stir-fry chicken tops the list of Asian-influenced restaurant best-sellers. Asian noodle bowls—the most often added to menus—are enjoying popularity as Uncle Ben’s and Healthy Choice frozen bowl entrees. Dim sum, pot stickers, sushi, and sashimi were selected as up-and-coming menu “Rising Stars.” And tempura vegetables, pad Thai noodles, skewered marinated Asian tidbits, and dipping sauces for satay are meeting our growing desire for more savory hearty snacks and bite-sized meals.

While soy, sesame, teriyaki, ginger, and garlic have all become mainstream, the demand for Asian varieties of spices and herbs, as well as unique Asian vegetables, is creating premium markets for U.S. growers and ingredient suppliers alike. Flavorful but familiar vegetables such as ong choy (water spinach), gai lan (Chinese broccoli), dau mui (snow pea shoots), and gai choy (Chinese mustard cabbage) range from spicy to bitter. Chefs are also tapping into sea vegetables, with Japanese seaweed salad perhaps the most familiar.

Other new directions will be forthcoming. Many Asian dishes have both a highly compelling sweet but somewhat bitter flavor—due to unique local vegetable or other indigenous varieties of herbs—which may well find a niche among America’s more sophisticated diners. For example, rau ram, Vietnamese or Cambodian mint, has a pungent licorice flavor essential to Thai, Malaysian, and Indonesian cooking and Pho, the well-known Vietnamese noodle soup.

In addition, we’ll be seeing more use of fresh herbs, used raw and not only sprinkled on food but also eaten and appreciated as a vegetable. For example, lettuce leaves and a variety of fresh herbs form a table salad. Shredded herbs are tossed with rice noodles and grilled meats, while leaves of Vietnamese mint double as wrappers. Herbs are used in greater amounts. Green perilla— shiso in Japan—cousin to basil and mint, tamarind, and pandanus leaf, described as the Asian vanilla, are sure to gain culinary attention. Creatively flavored rice paper, wonton, and egg roll wrappers will be increasingly in demand. Lighter-flavored sauces for dipping or simmering, broths and fruit reductions for cooking, rice vinegar dressings, and creative “fillers” for these tasty mini-morsels will soon be in mass-market demand.

The present established Chinese, Japanese, and Thai food in America will pave the way for more specific regional cuisine, such as Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Burmese. If I had to pick, I’d bet on Vietnamese. After all, the U.S. Vietnamese population is estimated at seven times the Thai segment. Its cuisine—healthy, fresh, light but flavorful—is somewhere between Chinese and Thai, not too hot, too sweet, or too pungent. It has an abundance of seafood and a wealth of bold spices due to its closeness to Thailand, India, and China and a century of French influence, with food as a strong focus. You’ll even find Vietnamese versions of bouillabaisse, asparagus/crab soup, and crepes. Lemon grass, basil, mint, fish sauces, shallots, tamarind, coconut, curry leaves, and cilantro are all key to the cuisine.

Last, but not least, while the Asian influence has brought us a wide variety of enticing forms and flavors, it has also placed new and emerging demands on food marketers, highlighting freshness and a new need for exquisite presentation. Looking fresh, healthy, and colorful is key. Watch for interesting specialty items like Thai eggplant, pea eggplant, and mango to impart color. Plating over vegetables and grains, the freshness/seasonality of fish, herbs, and vegetables, and the time from “dock to wok” will get unprecedented attention by chefs. Whether Asian cooking is moving mainstream or if mainstream demands are moving toward the Far East, one thing is sure—it will dominate the next millennium of cooking, American style.

by A. ELIZABETH SLOAN

Contributing Editor