Regulation of Functional Foods and Dietary Supplements

Companies developing new food products must decide which approach—functional food or dietary supplement—they want to take and be knowledgeable about whether the health claims they want to make are allowed.

Companies developing new food products that will be promoted in the United States with a focus on health must, of course, be aware of the latest research developments on the health benefits of each of the ingredients that can go into a food. But they must also decide what health-related claims they hope to make for the new product and be knowledgeable as to whether such statements are allowed.

Since different claims are allowed in different food categories, a company must know something about the federal regulation of claims in each of these groups. Food categories for which federal definitions exist include food and dietary supplement, but not functional food or nutraceutical. These latter two terms, however, are broadly used by marketers and the media and can be described within the context of the defined terms.

This article will provide background about each of the food categories in which a food in conventional form can be sold, including definitions and some information on the regulations that govern health-related claims for each of them. In addition, the status of “new” ingredients in each of these categories is discussed.

Definitions

The regulatory classes available for food products are limited to those set out by the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) and are determined not by the contained ingredients but rather by the intended use (e.g., label claims, advertising, oral or written statements, etc.) of the product. The act defines food as “articles used for food or drink for man or other animals, chewing gum, and articles used for components of any such article” (21 USC 321(f)). Two special categories of food are also defined in the act:

Medical food, defined as “a food which is formulated to be consumed or administered enterally under the supervision of a physician and which is intended for the specific dietary management of a disease or condition for which distinctive nutritional requirements, based on recognized scientific principles, are established by medical evaluation” (21 USC 360ee (b)(3)).

Dietary supplement, a special class of food defined by the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994 (U.S. Public Law 103-417) as a product that is labeled as a dietary supplement and “intended to supplement the diet,” and that “bears or contains . . . a vitamin . . . a mineral . . . an herb or other botanical . . . an amino acid . . . a dietary substance for use by man to supplement the diet by increasing the total dietary intake, or . . . a concentrate, metabolite, constituent, extract or combination of [any of the above].”

DSHEA also limited the forms in which dietary supplements are allowed to be sold. Common forms such as tablets, hard-shell and softgel capsules, powders, and liquids intended for consumption in small quantities (e.g., measured in drops) are all acceptable forms. In addition, and most important for purposes of this article, dietary supplements are allowed to be sold in conventional food forms so long as the product “is not represented as conventional food and is not represented for use as a sole item of a meal or of the diet” (21 USC 350 (c)(1)(B)(ii)).

Nutraceuticals vs Functional Foods

That a food-based product might provide a benefit that goes beyond its nutritional value is not a new idea, and the terms to describe such products have been varied. Names such as designer food, pharmafood, and phytoceutical have come and gone, and today we most often hear reference to functional foods and nutraceuticals. The meanings of even these two terms has varied, and, as mentioned above, neither of these terms has any legal status in the U.S. at this time.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

This U.S. experience is repeated throughout the world, with a notable exception in Japan, where a class of goods known as “foods for specific health uses” (FOSHU) has been defined by regulation and may include foods that assist in the prevention or recuperation of specific diseases, for example. The Canadian health authorities are also actively grappling with these terms and have recommended policy options for health claims on food products, providing the following definitions (from www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hpb-dgps/therapeut/zfiles/english/ffn/nutra_pol_e.html):

• A nutraceutical is a product isolated or purified from foods that is generally sold in medicinal forms not usually associated with food. A nutraceutical is demonstrated to have a physiological benefit or provide protection against chronic disease.

• A functional food is similar in appearance to, or may be, a conventional food, is consumed as part of a usual diet, and is demonstrated to have physiological benefits and/or reduce the risk of chronic disease beyond basic nutritional functions.

In the meantime, there is no reason to think that any progress will be made by U.S. regulators in coming to terms with these words. The Nutraceuticals Research and Education Act (NREA)—modeled after the Orphan Drug Act—was introduced in Congress on November 1, 1999, but has not yet been acted on. The Food and Drug Administration has taken the position that since Congress has provided no legal guidance, it is up to the agency to define this class of foods, and FDA has stated its confidence that the existing regulations for foods are sufficient.

Health-Related Claims

Health-Related Claims

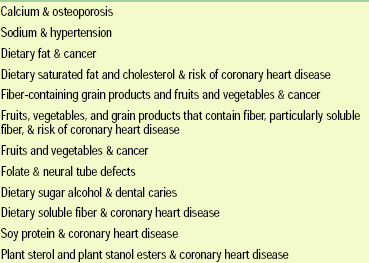

The health-benefit claims that are allowed to be made for conventional foods are generally limited to statements that are defined as “health-related claims.” A health-related claim is defined as one that “characterizes the relation of [certain] nutrient[s] . . . to a disease or health-related condition” (21 USC 343 (r)(1)(B)). All health claims are required to be approved by FDA in advance of marketing. So far, 12 health-related claims have been approved (Table 1).

Broader claims are accepted for dietary supplements than for common foods. To begin with, health-related claims like those allowed for conventional foods are also allowed for supplements. In addition, claims described in DSHEA as “statements of nutritional support” and usually referred to as “structure/function claims” are also permitted. This type of claim can only be made if it is substantiated (though no specific or standardized substantiation protocol has been established), if FDA is informed of the claim within 30 days of marketing, and if it is disclaimed on the product’s label.

One restriction in common for both health-related claims and structure–function claims is that they must not be “drug claims”; i.e., they must not identify a product as able to treat, prevent, cure, mitigate, or diagnose any disease or disease symptom. This restriction is relevant both to direct statements and to implied claims, such as might be made with a product’s name.

Ingredient Considerations

Safety standards established by federal regulations prohibit any food product, including a dietary supplement, from being adulterated. A food is adulterated if it contains any poisonous or deleterious substance in an amount that may render it injurious to health (21 USC 342 (a)(1) and 346). Many of the ways in which a conventional food or supplement could be adulterated are essentially the same, such as adulteration from filth, unapproved radiation, or inclusion of an unapproved pesticide.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

In addition, a conventional food can be deemed to be adulterated if it contains an unapproved food additive. Similarly, a dietary supplement is adulterated if it contains an unapproved new dietary ingredient. There are both regulatory similarities and differences between these two terms.

The federal definitions of both food additive and new dietary ingredient include a “grandfather” concept that reflects their separate dates of adoption. Thus, food additives that were already included in foods prior to January 1, 1958, and dietary ingredients that were marketed prior to October 15, 1994, are exempt from definition as “new.” Any new ingredient intended for use in a food or dietary supplement must go through an approval process to come into the market legally.

There are significant differences in the processes involved, however. Substantiation of the safety of a food additive is done by a well-developed regulation that has been implemented over several decades. This process is specifically described to require that the substance is generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by qualified experts on the basis of scientific procedures or have a documented history of food use prior to January 1, 1958 (21 USC 321 (s)).

The procedure that governs new dietary ingredients, by contrast, consists only of the statutory language of DSHEA, as no regulations have been promulgated to date. Nevertheless, a notification procedure is required, and the law states that information to support a manufacturer’s contention that the ingredient will “reasonably be expected to be safe” must be submitted to FDA.

A significant difference between these two classes of “new” ingredients is in the sheer number of “grandfathered” substances. Since hundreds of botanicals have been marketed for many years, the list of herbs that are considered not to be novel is lengthy. Somewhat bizarrely, this results in a regulatory situation where the same ingredient in the same form and quantity (or even greater quantity) is allowed to be sold in a dietary supplement, but would require conformity to the food additive provisions if used in a food.

Manufacturing Practices

At present, the federal regulations that control current good manufacturing practice (cGMP) for manufacturing and/or handling food in interstate commerce (21 CFR Part 110) also applies to dietary supplements. An Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking for a cGMP specific to dietary supplements was published by FDA on February 6, 1997 (62 FR 5699-5709) but has never been implemented. The agency is reportedly engaged in furthering the rulemaking process, but it has been more than four years now and we are still without a proposed rule. In the meantime, the ANPR, though it does not have the force of law, is a useful (though informal) guidance document.

Examples

The evolving regulatory approach that governs the marketplace for “functional foods” is probably best illustrated by a few examples from the recent past that demonstrate most of the issues discussed above.

• Benecol®. McNeil Consumer Healthcare bought the rights to Benecol, a cholesterol-lowering product that incorporates plant stanol esters from pine oil into a canola oil margarine, from the Finnish company Raisio Group that had developed it. The product had been on the European market for several years, and company literature describes more than 20 clinical studies demonstrating the safety and efficacy of the product.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

McNeil sought to introduce the product in the U.S. as a dietary supplement, probably calculating that this class of food presented the lowest set of regulatory hurdles. The label and product literature for Benecol were submitted to FDA, as required when structure–function claims are to be made for a dietary supplement. Although they bore the appropriate statements of identity and disclaimers, the materials represented the product as a “replacement for butter or margarine” and promoted the flavor and texture of the product. Vignettes depicted the product in butter or margarine uses, and the product was claimed to help manage cholesterol “naturally through the foods you eat.”

After examining these statements, FDA concluded that Benecol was represented as a conventional food—margarine—and was therefore not a dietary supplement. The agency further concluded that sitostanol esters were a new ingredient added to a conventional food and that there was no basis to conclude that these substances are GRAS. Following FDA’s decision, McNeil agreed to an FDA review of GRAS self-affirmation data. The agency completed a 90-day review and accepted the company’s determination that sitostanol ester was GRAS and allowed the product to be marketed as a conventional food.

• Kitchen Prescription®. The Hain Food Group, Inc., submitted a notice of claims for its new Kitchen Prescription line of soups (e.g., Chicken Broth and Noodles with Echinacea), accompanied by labels, to FDA, asserting that the products were dietary supplements. The agency reviewed the materials and concluded that the pictures of soup, use of the word “soup,” use of the phrase “Heat ’n Serve,” and references to tomatoes, split pea, chicken broth, and noodles on labels and in vignettes served to represent the products as conventional foods and were therefore intended to do other than supplement the diet.

According to DSHEA, echinacea and St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum), ingredients in these products, are not new dietary ingredients if present in a dietary supplement product. However, they are new food ingredients if present in a conventional food. Under FDCA, an ingredient intentionally added to conventional food must be used in accordance with a food additive regulation unless it is GRAS for its intended use. In its review of the labels and claims, the agency reported that it was “not aware of a basis for concluding” that St. John’s wort and echinacea are GRAS for general use in conventional food. Conventional foods containing these ingredients would thus be considered adulterated under the Act.

FDA also found that the structure–function claims made on the label were inappropriate for a conventional food. Finally, the name of the product line, Kitchen Prescription, was found to suggest that the products may have been intended to diagnose, cure, mitigate, or treat a disease (implied drug claim) and are thus unapproved new drugs.

FDA’s letter to the company prohibited sale of the products as dietary supplements, but allowed that they might be sold as conventional foods if the ingredients are shown to be safe (GRAS) and if the labeling is brought into compliance with requirements for conventional food. Specific recommendations were that the company change the label so that it does not suggest an effect on disease (“prescription”); that structure–function effects, if claimed, are achieved via nutritive value; and that the label be brought into compliance with NLEA (e.g., include a “Nutrition Facts” panel rather than a “Supplement Facts” panel). After further conversations with FDA, the company decided to remove its products from the marketplace.

• EggsPlus®. These nutritionally enhanced eggs produced by Pilgrim’s Pride contain a higher than normal amount of vitamin E and omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids as a result of an innovative feeding regimen. The health benefits of these nutrients are prominently featured in the product’s marketing. These eggs are sold as conventional food, albeit one with perhaps a more attractive nutrient profile compared to other normally produced eggs. Because these nutrients are not added as separate ingredients they do not fall under the status of dietary supplement materials. This product remains in the dairy case as an approved version of an already existing food.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

• Viactiv®. McNeil Nutritional’s Viactive “soft calcium chews” are labeled and marketed as dietary supplements. The advertising for this product relies on the health claim for calcium and osteoporosis, but also emphasizes attributes such as flavor (“delicious”) and limited calories (“just 20”) that have been traditionally related to foods. These chews are intended to supplement the diet and are not represented as a food.

• Supplement Beverages. In February 2000 and in June 2001, FDA sent warning letters to several beverage manufacturers that were including herbal ingredients in their juice products. The letters took the position that, since the products were marketed as conventional foods, the herbal ingredients should be treated as unapproved food additives and that their presence in the food constituted adulteration.

In July 2001, the American Herbal Products Association wrote to FDA its opinion that “dietary supplements in beverage form are a lawful products category,” so long as such products are not represented as conventional foods. On November 8, 2001, FDA responded that it “does not object to a dietary supplement being marketed with the physical attributes that are essentially the same as a conventional food as long as the dietary supplement product is accurately labeled and not represented for use as a conventional food.”

The agency provided examples of labeling that it would view as conventional food representation, such as the use of a standardized food name like “spring water” or “orange juice,” or of a traditional food term like “drink,” “beverage,” “cereal” or “soup.” The letter also stated that the physical location of a product in the marketplace or a representational vignette, like a bowl of soup, would also be seen as representation as a food.

In its letter to FDA, AHPA had also stated the opinion that supplements are allowed to taste good and to be described by taste, and that a supplement’s nutritive value should be allowed to be disclosed. While the agency did not respond to the latter concern, it agreed that there would be no objection “at this time” to a “simple direct or indirect representation of flavor . . . provided the flavor designation does not otherwise reference the product’s use as a conventional food.” “Herbal supplement in an orange flavored base” was provided by FDA as an example of such a flavor-related statement.

These beverages remain in the marketplace with essentially the same ingredients and labeling two years after the communications were first received from FDA. Time will tell if beverages with added dietary supplement ingredients can be sold as dietary supplements or must be considered as conventional foods.

Choosing an Approach

The most important federal regulations affecting the marketplace for products with non-nutritional health benefits are those dealing with regulatory categories, label and marketing claims, and new ingredients. Considerably less premarket review may be required of an ingredient with an established history of use if a product is marketed as a dietary supplement in food form rather than as a conventional food. Of greatest significance to those who intend to market a new product as a dietary supplement, however, is the need to assure that they are not representing their product as a conventional food.

Though there are other regulatory differences between these two classes (e.g., labeling of “Nutrition Facts” vs “Supplement Facts”), these apply only after “intended use” of the product as food or dietary supplement has been established, and they are of a more detail-oriented nature.

The rules for dietary supplement products in their usual form (pills, capsules, liquids in dropper bottles, etc.) are relatively straightforward. Food-form products that have run afoul of FDA in the recent past have done so because they made drug claims on the label and/or because the design of the label was such that products whose intended use was to supplement the diet (i.e., dietary supplements) could not be differentiated from conventional food. The unapproved food additive problem usually does not arise if intended use as a dietary supplement can be unambiguously ascertained from the label and the product form. Most important, the dietary supplement identity of the product must be clear. Finally, labeling and advertising must maintain a consistent supplement theme.

Successful introduction of Benecol and EggsPlus as conventional foods and Viactiv as a dietary supplement indicate that innovative foods can be successfully introduced to the American market as long as product design and marketing are undertaken in an environment where there is a good understanding of the regulatory system by which they are governed.

The author is Vice President for Scientific and Technical Affairs, American Herbal Products Association, 8484 Georgia Ave., Suite 370, Silver Spring, MD 20910.