Chile Peppers: Heating Up Hispanic Foods

Chile peppers, which play a central role in Hispanic cuisine,continue to grow in popularity for their desirable pungency.

Chiles have played a central role in the Hispanic culture that today envelops New Mexico, Arizona, and parts of southern California, southern Colorado, and western Texas, as well as Mexico. The nature of the Hispanic culture can be seen in all of these places, whether it be the ristras, red chile pods that have been strung and hung to dry outside homes or businesses, or the green chiles rellenos that so many people come hundreds of miles to taste.

Although the Hispanic culture has traversed borders and spread throughout the Northern Hemisphere, the course of Hispanic history in New Mexico is the beginning of the story of Hispanic life in America. The influences of Hispanic culture have touched, and continue to touch, the lives of all Americans in as prosperous and significant a way as other strands of our nation’s cultural mosaic. One example is salsa’s surpassing ketchup as the nation’s No. 1 condiment more than 10 years ago.

We know that the people of Mexico and Latin America who came up the Rio Grande in the late 16th century shared much with established Native American culture. The new culture garnered its own sense of uniqueness and sent its roots deep into New Mexico and the southwestern United States, becoming a central part of the culture there. The essence of any culture is its ability to move into the future while retaining its tradition, history, and uniqueness. Chile has been a prominent element with every long-established Hispanic grower, whether it be one acre or 100 acres, for more than 400 years in the southwestern U.S.

History of Chile Peppers

Chiles originated in a remote area of South America between the mountains of Brazil and the lowlands of Bolivia more than 1,000 years ago. Over thousands of years, the wild chiles that looked much like small, red berries were moved out of this area and disseminated by birds. Through time, a symbiotic relationship between birds and chiles evolved because birds lack the receptors that feel pungency and harbor digestive systems that do not harm the seed of the chile pepper. Conversely, mammals feel pungency, and their digestive systems crush the seed.

People are probably not supposed to eat chiles—the pungency is supposed to deter us. But strangely enough, humans started to cultivate these very pungent, wild chiles. Year after year, humans began to select for larger, different colored pods and eventually ended up with a large number of varieties of chiles, very different from their wild predecessors.

Chiles have been carbon dated back to 7000 B.C. at archeological sites in southeastern Mexico. Fossilized chiles much larger than the wild types have been documented back to 2500 B.C. in Northern Peru, suggesting cultivation at that time. One theory of anthropologists is that Indians of central Mexico cultivated chile peppers and started to trade chiles with Indians from the North; another is that chiles ended up hundred of years ago in the southwestern U.S. as Spanish explorers collected them along the trade routes.

Chiles are a Western Hemisphere crop that got back to the East with some help from explorers. Record books indicate that Columbus, looking for black pepper (Piper nigrum), the most expensive spice at the time, came across these fiery pods and returned with these unique fruits because of their pungency. Today, chiles are global, found and cultivated in almost every country in the world. They are staples in many ethnic diets, including Thai, Chinese, Korean, Indian, Hungarian, African, Mexican, and others. Chiles are used in these cuisines in both the dried and fresh forms. They are also considered a spice in many countries because of the extensive use of paprika, which can be pungent or non-pungent.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Varieties of Chile

Chiles are relatives of other plants in the Solanaceae family, which includes potatoes, tomatoes, and eggplants. There are many different varieties, colors, shapes, sizes, and even names. When speaking of the plant (Capsicum) or any fruit from the plant, the correct spelling is chile; however, this differs throughout the world—the British prefer chilli, while Asia and India prefer chilie. Chiles also go by many different terms—hot peppers, chile peppers, chiles, and aji are just a few. The word chile comes from the Nahuatl language of the Aztecs, and in many parts of Central and South America chili is called aji. Nevertheless, chiles have become part of the world’s cuisine and a passion for millions of gardeners regardless of what they are called.

Chiles are grown all over the world. The top chile-producing countries are China and Mexico, with Spain and the U.S. not far behind. States that produce chile on a large scale include New Mexico, California, Arizona, Florida, and Texas. However, chile peppers are becoming favorites in gardens all over the U.S. The Chile Pepper Institute—a nonprofit organization (www.chilepepperinstitute.org) that seeks to educate the world about chiles—gets thousands of requests a year for new varieties of chile seeds from all parts of the U.S. These fiery pods are gaining popularity in homes not only for their uniqueness but also because they are low in sodium, cholesterol free, low in calories, high in vitamins A and C, and part of today’s “healthy” lifestyles.

Scientifically, chiles are described by pod type—the overall shape and size of a particular chile—and the species. In addition to an endless number of wild species, there are five domesticated species of chiles in the world today:

•Capsicum annuum, the largest species in the Capsicum genus, houses more than a thousand different varieties, including jalapeño, New Mexican, bell pepper, Serrano, cayenne, and ancho. All of these are also different pod types, with hundreds of different varieties within those pod types.

•Capsicum chinense, another popular species, accommodates pod types like the habanero and the scotch bonnet and also includes some of the worlds hottest peppers. Varieties within these pod types include the ‘Red Savina.’ which is currently the world’s hottest scientifically tested chile, and the ‘Red Caribbean.’

•Capsicum frutescens includes the beloved ‘Tabasco.’

• Capsicum baccatum includes most of the true ajis. A “true aji” is a pod type within baccatum that includes many different varieties. The distinction is made here because aji is a term used loosely in the U.S. and other parts of the world to describe any type of chile.

•Capsicum pubescens includes the ‘Rocoto’, a favorite of chile aficionados around the world for its black seeds.

The following are some of the more popular pod types:

• New Mexican. This pod type was developed around 1907 by Fabian Garcia, a horticulturist at the New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanical Arts (now New Mexico State University) and is the most widely used chile in American Hispanic cuisines. Garcia was trying to develop a pod for the “Gringos.” Most of the varieties being used in Mexican cuisines were too hot for most Anglo people. He started breeding different varieties of the Mexican pasilla and Colorado chiles and eventually released New Mexico No. 9, which today is known as the granddaddy of all New Mexican chiles.

In 1896, Emilio Ortega (at the time sheriff of Ventura County, Calif.), after visiting southern New Mexico, brought back chile seeds and planted them near Anaheim, where they adapted well to the soil and climate and were given the name Anaheim. Although this name has stuck with this particular pod type for many years, it is truly a New Mexican with ‘Anaheim’ just being a variety under that pod type. Other varieties include ‘NuMex Joe Parker,’ ‘Sandia,’ and ‘NuMex Big Jim,’ which is in the Guinness Book of World Records as the biggest chile ever grown, 13 inches long. These chiles are used for New Mexican style chiles rellenos, green chile sauces, red chile sauces, enchiladas, stews, and many dried powders.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

To really understand the types of chiles grown in New Mexico for centuries, one would have to acknowledge differences between Northern and Southern New Mexico chile varieties. The “Nativos” are New Mexican chiles that have been grown for hundreds of years and are now known as land races in many areas of Northern New Mexico along the Rio Grande Valley. Looking more like a Colorado chile than the New Mexican pod types produced on large scales today, these chiles are square-shouldered and medium in size, usually ranging between 4 and 5 inches in length, larger at the stem end and tapering to a point at the blossom end. These chiles are always green when immature, turning to red at maturity and having a pungency level ranging from medium-hot to very hot, depending on the season and growing conditions. Many small chile farmers and home gardeners grow this chile today for its unmistakable flavor and high demand at the farmer’s markets in Española, Dixon, Taos, and Santa Fe.

The chiles being grown 350 miles south are more like the standard New Mexican type and have a sloping, almost-round shoulder separating the chile from the stem and heat levels ranging between medium and hot. These chiles are picked at both stages, immature green and mature red.

• Bell Pepper. Also known as a sweet pepper, this is the most popular and widely grown pod type in the U.S. There are hundreds of different varieties in this pod type and a range of colors that shames the rainbow. Some varieties include ‘California Wonder,’ ‘Dove,’ ‘Jupiter,’ and ‘Big Bertha.’ Mature colors can be every shade of yellow, green, red, orange, purple, and even brown

• Jalapeño. This is another popular pod type in the U.S. It has gained much notoriety in recent years because of such products as “Jalapeño Stuffers”—whole jalapeño pods stuffed with a variety of ingredients, usually cheese, then breaded and deep fried and often served as an appetizer. The jalapeño pod type includes such varieties as ‘NuMex Primavera,’ ‘TAM Mild,’ ‘Veracruz,’ and ‘Mitla.’

• Cayenne. This pod type includes such varieties as ‘Mesilla,’ ‘NuMex Nematador,’ and ‘Ring of Fire.’ It is used primarily as a dried ground spice and also processed into mash that is later made into hot sauce.

• Habanero. This pod type is a more tropical chile and is grown in areas like Southern Florida, the Bahamas, and Jamaica. It has a very distinctive aroma that is different from most other chiles and is used fresh or dried as a jerk spice, in fruit chutneys, and in other salsas and rubs.

• Tabasco. This pod type, one of the few in the very small frutescens species, was first cultivated by the McIlhenny Co. in Avery Island, La., more than 100 years ago. This very hot little chile has become extremely popular and is the basis for the No. 1 selling hot sauce in the world, Tabasco® Sauce.

Pungency

Chiles are the only cuisine that can initiate pain and pleasure in one sitting. They are also said to exhibit addictive qualities. When people come to the Southwest and stay for an extended period of time, they go away with that craving for their favorite recipe. Humans, chimpanzees, dogs, goats, and a variety of other mammals have all been observed exhibiting addictive qualities to this powerful fruit. The compound that is addictive is capsaicin, a complex of amides that are incredibly pungent. The human tongue can detect these compounds at one part capsaicin in a million parts liquid.

In 1912, a chemist named Wilbur Scoville developed a method that measured the heat level of chiles. The test is called the Scoville Organoleptic Test. In his experiments, Scoville blended various pure ground chiles with a sugar water solution. The solutions were then given to a group of testers who tasted the solutions in increasingly diluted concentration, until they reached the point at which the solutions no longer burned the mouth. Each time the solution was diluted, it was given a number, and these numbers were added to create the Scoville Heat Unit of measurement.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

However, the technique was subjective and depended on the taster’s palate and its response to the pungency of chiles. The accuracy of this test is often criticized. Years later, a test method involving high-performance liquid chromatography was developed. In this procedure, chile pods are dried and ground; the chemicals responsible for the pungency are extracted; and the extract is injected into the chromatograph for analysis. This method measures the total heat present as well as the individual capsaicinoids present, and the results are converted into Scoville Heat Units by a mathematical equation.

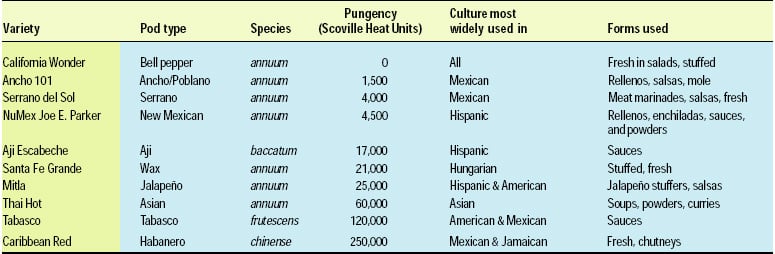

Chiles have a wide range of pungency (Table 1), which is affected by the environment in which the chile was grown. Many people believe that capsaicin resides in the seeds, but this is not true. Capsaicin is only produced in the placenta of the chile pod, the “ribs” in the interior of the pod, where the seeds are attached. When a chile is processed, the capsaicin glands burst or break and the oils containing the yellow-orange capsaicin penetrate the seed coat, making it pungent.

One of the most frequently asked questions at the Chile Pepper Institute is “How do I stop the heat?” The casein in dairy products helps break the binding site between capsaicin and skin receptors. Therefore, any dairy product will help ease the pain, and this is more than likely why many Mexican cuisines have cheese or sour cream added.

Chile Pepper Industry

Chiles are grown worldwide, and the number of acres produced grows exponentially every year. Asia, the country producing the most, harvested 8,238,000 metric tons in 2001, followed by Mexico with 1,961,000 metric tons and the U.S. with 885,630. Other top chile-producing countries include Indonesia, Turkey, Spain, and Nigeria. These statistics include hot peppers as well as sweet peppers.

Of the 885,630 metric tons produced in the U.S., New Mexico comes in first, producing more than 100,000 metric tons of hot peppers alone in 2001, giving the state a $60-million harvest. New Mexico also processes much of its crop, quadrupling that harvest amount.

Chiles can be processed in many different ways, frozen, canned, dehydrated, or pickled. One of the varieties that is grown and processed in that New Mexico state is cayenne. Cervantes Enterprise, a grower/processor in southern New Mexico, grows the cayenne and produces the mash that Louisiana Hot Sauce is made from. The cayennes are grown, harvested, and then transported to the processing facility by truck. There the pods are cleaned, sorted, and packed into barrels where it will ferment. After fermentation, the mash is then transported by tanker loads to the Louisiana bottling facility and packaged.

The popularity of chiles grows every year, with large numbers of large-scale growers popping up all over the U.S. and no decline in demand seen in the future. Even though chiles initiate pain in more than 1.3 billion consumers all over the world, it is a pleasurable pain that one-fourth of the world’s population tends to enjoy over and over again.

by Danise Coon

The author is Assistant Director, Chile Pepper Institute, New Mexico State University, Box 30003, MSC 3Q, Las Cruces, NM 88003.