Increasing Whole Grain Consumption

Whole grains offer health benefits, but Americans consume less than the recommended three servings per day. Here’s how to bridge that gap.

For consumers to receive the healthful benefits of whole grains, the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends the consumption of at least three servings of whole grain (3 oz) per day; mypyramid.gov recommends that at least three servings from grains be whole grain; and Healthy People 2010 endorses three servings of whole grain per day for at least 50% of the population older than 2 years of age by the year 2010 (USDA/HHS, 2005a, b; HHS, 2000).

More than 650 whole-grain products have been introduced in 2005 alone, many from large manufacturers like General Mills, Sara Lee, and Campbell Soup Co. (ACNielsen, 2005), despite the lack of a clear Food and Drug Administration definition of what constitutes a whole-grain food. Yet typical daily consumption of whole grains is just one serving/day (Cleveland et al., 2000). Why a gap between recommendations and intake exists isn’t clear. And how we bridge the gap to help consumers eat more whole-grain foods will take more effort on the part of industry, government, and academia.

Whole Grains Defined

Whole Grains Defined

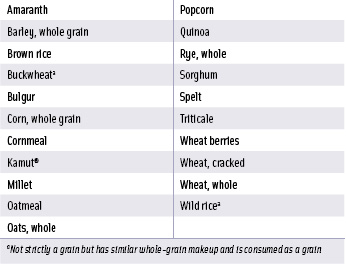

Whole grains have been part of the human diet for centuries. The number of commonly consumed whole grains has grown from just wheat, oats, and barley to include many others (see table below).

Grains are made up of three main parts: the innermost germ, which contains the plant embryo or seed; the endosperm, which serves as food for the growing seed; and the outer hull which contains the bran and helps to protect the grain from insects, bacteria, molds, and severe weather (Fulcher and Rooney-Duke, 2002). To be a whole-grain food, all three parts of the grain must be included.

The bran and germ supply the majority of biologically active components found in the grain: amino acids (protein building blocks), B vitamins (thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, and pantothenic acid), and minerals (calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, sodium, and iron). The endosperm is mainly starch. Whole grains also contain a host of phytonutrients—plant components that offer health benefits—such as phytates, phytoestrogens, lignans, phenols, and antioxidants.

To be used as food, whole grains are processed into different forms. As whole grains are milled to make white refined flour, the outer bran layer and much of the germ are removed, taking away much of the fiber and many of the vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients. Despite enrichment to add back some of the nutrients lost during milling, the end products are different and are not considered whole grain. In contrast, whole-grain flour or whole-wheat flour retains the nutrients and all three parts found in the native grain—hence the name whole grain.

The Whole Grains Council (WGC, 2004), adapting the AACC International (2000) definition, defined whole grains as "foods made from the entire grain seed, usually called the kernel, which consists of the bran, germ, and endosperm. If the kernel has been cracked, crushed or flaked, it must retain nearly the same relative proportions of bran, germ and endosperm as the original grain in order to be called whole grain."

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Linking Whole Grains to Health

The 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans concluded that consuming at least three servings (3 oz) of whole grain/day can reduce risk of diabetes and coronary heart disease (CHD) and can assist with weight maintenance, based on strong evidence from numerous scientific studies.

• Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) and diabetes are among the top causes of death for both men and women in the United States and around the world. These diseases may be predicted by the occurrence of metabolic syndrome—a blend of conditions that may include obesity (particularly around the middle abdomen), elevated blood lipid levels, high blood pressure, insulin resistance, and glucose intolerance. If the syndrome is undiagnosed and untreated, it can progress to diabetes and may be a risk factor for CVD (Lorenzo et al., 2003).

Epidemiological data and clinical studies show a strong association between whole-grain intake and a reduction in risk of CHD among both men and women (Anderson et al., 2000; Jacobs et al., 1998; Liu et al., 1999). Taken collectively, the studies strongly suggest a 20–30% decrease in risk of CHD with three or more servings of whole-grain foods daily. Liu et al. (1999) showed that women who ate the highest level of whole grains daily had half the relative risk of developing CHD that those who ate the fewest whole grains had.

Diet, in addition to other lifestyle factors, can play a role in both contributing to the development of diabetes and helping to prevent it. Several major epidemiological studies (Salmeron et al., 1997a, b) showed an inverse relationship between whole-grain consumption and the risk of developing type 2 diabetes—the more whole grain consumed, the lower the risk of developing diabetes.

• Weight Management. Liu et al. (2003) found that over a 12-year period, women who ate at least three servings of whole-grain foods/day gained significantly less weight than women who ate only foods made from refined white flour.

Other studies suggest that because whole-grain foods typically contain more fiber, there is a link between fiber intake and health as well. There is a growing body of evidence that the dietary fiber—particularly soluble fiber like beta-glucan from oats and barley—plays a role in management of body weight, blood pressure, and blood cholesterol (FDA, 2003a; Brown et al., 1999). Ludwig et al. (1999) showed that as more fiber is consumed, less weight is gained over a prolonged period of time—about 8 lb in 10 years.

Additional studies suggest that when whole-grain intake is increased, body mass index (BMI), a standard measure for weight-to-height appropriateness, decreases—indicating a healthier body proportion among eaters of whole-grain foods (Koh-Banerjee et al., 2004; Ludwig et al., 1999). Fiber tends to fill the gut, often helping to decrease the number of calories consumed. Over time, consumption of more whole grains, more fiber, and fewer calories can lead to weight loss or, better yet, long-term weight maintenance—certainly relevant to the growing levels of obesity plaguing the U.S.

Data and Definitions Essential

Without a surveillance system in place to benchmark current whole-grain intake among different population groups today, it will be difficult to measure progress toward greater whole-grain consumption in the future. Developing biomarkers such as alkyl resorcinol for specific grains and grain components may provide another way to assess intake of grains. As a next step, trying to link the intake of whole-grain foods to positive long-term health outcomes, such as obesity, diabetes, and CVD is needed.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

A collaborative effort among academia, industry, and government groups to share new product nutrition data and incorporate the data into nutrient databases is crucial. Adding whole-grain information to nutrient databases, such as the University of Minnesota’s Nutrition Data System/Nutrition Coordinating Center (www.ncc.umn.edu) and the USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference (www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/search) is key as well.

The regulatory definition for whole grain is unclear, and having different descriptions around the globe only adds to the confusion. Being able to bridge the gap, in part, depends on the swiftness of FDA to create a standard for whole-grain food and to determine appropriate portion sizes. Quick action by FDA will permit consistent labeling and promotion of whole-grain foods. Consistency will increase consumer trust and help provide a clearer link between whole-grain science and messaging—similar to the language and rigor used for the whole-grain health claim: "In a low-fat diet, whole grain foods like [name food] may reduce the risks of heart disease and some cancers" (FDA, 1999). International whole-grain labeling standards should follow and work toward consistency.

Additionally, the amendment to the whole-grain health claim spearheaded by Kraft Foods (for whole-grain foods to contain less than 6.5 g total fat) allows for greater participation.

Consumer Confusion

Despite the recommendations to consume at least three servings of whole grain daily, the average intake of whole grains is less than one serving/day, and it is estimated that less than 10% of the U.S. population consumes three servings/day (Cleveland et al., 2000)

It is not clear what the consumer perceptions, motivations, and barriers to whole-grain consumption truly are. Is it the brown appearance; taste or texture; lack of appeal to all family members; or real or perceived differences in cost or convenience that is driving some consumers away? Research is needed to determine why this gap between whole-grain need and intake exists.

One solution to narrow the gap is to gradually introduce whole-grain-containing foods into diets of skeptical consumers using one of six options:

1. Slowly add more whole grain into bread formulations for increased palatability.

2. Use white whole wheat instead of red to mask the brown appearance (similar to what Sara Lee has done with its Soft & Smooth™ White Bread Made with Whole Grain).

3. Use fine-particle-size flour to minimize texture changes.

4. Vary the grains—blending white wheat, red wheat, oats, and barley to improve flavor and whole-grain goodness.

5. Create more 100% whole-grain-food options.

6. Develop novel whole-grain-containing products in foods other than grains, e.g., extracted barley beta-glucan in beverages (Marquart et al., 2005).

Chan et al. (2005) served pizza made with a 50/50 mixture of ConAgra Foods’ Ultragrain™ white whole-wheat flour and refined wheat flour to elementary school children. The researchers did not note any differences in consumption or plate waste between the pizza made with the mixture and pizza made with only refined wheat flour. This indicates that there are opportunities for increasing whole-grain consumption even among children.

Besides reducing the barriers to whole-grain trial and acceptance, it is crucial to determine how to communicate the health benefits of whole grains. What are the key messages about whole grains that positively influence public interest, understanding, and purchase decisions regarding whole-grain foods? Messages must speak to health professionals and consumers alike—and must be tested in large-scale marketing campaigns and targeted health promotion initiatives. Collaborative work by research, government, and community that would allow piloting whole-grain-food usage in schools, retail markets, and restaurant environments is needed on a broad scale. Testing new materials and programs to educate health professionals about whole grains and health and how to promote consumption is missing at present.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

Technology and Innovation

Despite the hesitancy on the part of some consumers, others are embracing whole-grain foods, as evidenced by the large number of new product introductions in 2005. More than 650 new Universal Product Codes (UPCs) were introduced for whole-grain foods in the past year (ACNielsen, 2005). These changes represent an increase of 34%, or $54 million dollars in sales. General Mills has reformulated its entire cereal line to be whole grain, supporting it with advertising and package graphics and descriptive copy. Sara Lee introduced its whole-grain Soft & Smooth White Bread with all-family appeal in mind. Barilla® Whole Wheat Pasta and Creamette® Healthy Harvest Whole-Wheat Pasta are available nationwide.

Pepperidge Farm recently introduced Whole Grain Goldfish Snack Crackers, an alternative to the refined-grain snack loved by children. Frito-Lay launched Rold Gold® Honey Wheat Braided Twist Pretzels that contain whole-wheat flour in addition to traditional refined white flour. ACNielsen (2005) reports that sales of whole-grain crackers have increased by 10%—more than $300 million—compared to 2004. Bread manufacturers have reformulated their products to include more whole-grain or whole-wheat offerings. Sales of whole-grain breads have increased by 18%—$1.1 billion dollars in sales—compared to last year.

Whole-grain foods may also be considered as functional foods providing healthful benefits that decrease risk of disease. To help solve the growing concern about global obesity, scientists may want to explore various techniques such as hybridization, genetic modification, milling, and processing to help control the caloric impact of grain-based foods.Ultimately, consumers will be looking for modified foods that do not compromise product acceptability and health benefits.

Other opportunities include tapping into foodservice and restaurant channels to help increase whole-grain consumption. Of the one serving of whole grain consumed/day, only 15% is eaten away from home and only 6% comes from whole-grain foods consumed in restaurants (Kantor et al., 2001). Clearly, there is great opportunity for collaboration with chefs, restaurants, and the foodservice industry to help bolster whole-grain consumption.

An example of recent bakery success is Great Harvest Bread Co., a franchisor of retail bread bakeries with a network of 218 small stores in 41 states. Its sales of whole-grain breads and rolls have increased by 12% on average from last year to $77 million (Emmer-Aanes, 2005).

Moving Forward with Research

Clinical research studies must be conducted to document the beneficial effects of whole-grain foods. We need an organized pipeline of published findings to keep whole grains top of mind for research scientists, government groups, industry leaders, educators, and consumers. Solid science reporting helps to clarify whole-grain health benefits in our minds, allowing consumers to rely on real data rather than the current generalized belief that whole grains are good-for-you foods. To communicate effectively, we need a whole-grain food standard, consistent labeling, and messaging. With a standard in place, we can proceed to educate, market, and more effectively sell whole-grain products.

Whole-grain product innovation must incorporate taste, texture, color, and other sensory properties that will allow a majority of refined-grain eaters to gradually adapt to more-consistent whole-grain consumption—close to three servings/day. We must evaluate grains, other than wheat and oats, for biologically active components to incorporate a greater variety of grains into the diet. There is tremendous opportunity to include components of grains into foods that are not grain-based, such as extracted barley beta-glucan in beverages (similar to sterols in juices and spreads) to determine effects on risk factors and disease.

--- PAGE BREAK ---

A volume of epidemiological data exists, yet there is a need for clinical trials to measure the effect of whole-grain intake on long-term health outcomes, including obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Research is lacking that would help to delineate the health effects attributed to whole grains from confounding lifestyle factors like exercising and not smoking that correlate with whole-grain intake but may or may not have any influence.

Working Together

Development and promotion of a campaign for whole grains, similar to the successful 5 A Day for Better Health program (www.5aday.gov), which includes a 5 A Day seal and promotion for fruits and vegetables in grocery stores and on restaurant menus, would help keep whole grains visible to more consumers. Also needed is collaboration among scientists, industry, government, educators, farmers, and organizations such as the American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, and American Diabetes Association.

When we speak with a common voice and mission to provide practical solutions, we will begin to narrow the whole-grain-intake gap. Together we can combine our strengths so that whole-grain consumption will meet and exceed the three servings/day that is beneficial to human health.

Promoting Whole Grains

A food must contain 8 g of whole grain/serving to be considered a good source of whole grains and 16 g to be an excellent source (FDA, 2004; WGC, 2005).

The Whole Grains Council has designed a set of stamps that food manufacturers, bakeries, and grocers can use to indicate that certain products are a good or excellent source of whole grains. The stamps were introduced in January 2005, and 43 different companies are currently using the stamps on more than 400 different items, ranging from cereals to soups, breads to bagels, and crackers to cookies.

The Good Source stamp is for foods containing a half serving of whole grains. The Excellent Source stamp goes on products offering a full serving of whole grains. And the 100%/Excellent Source stamp is for foods with a full serving of whole grains and containing no refined grains.

Some companies, such as General Mills and Sara Lee, have also developed their own graphics for use on their products to signify that they are a good source of whole grains.

Len Marquart, R.D., is Assistant Professor of Nutrition, Dept. of Food Science and Nutrition, University of Minnesota, 1334 Eckles Ave., St. Paul, MN 55108 ([email protected]) . Elyse A. Cohen, L.N., is President, Elyse Cohen Health and Nutrition Communications, Minneapolis, MN 55436 ([email protected]) . Send reprint requests to author Marquart.

www.ift.org

Members Only: Read more about whole grains online at www.ift.org. Type in the keywords in our search box in the upper left side of our home page.

References

AACC. 2000. Whole grain definition. AAAC, Intl. Cereal Foods World 45(2): 45-88.

ACNielsen. 2005. AC Nielsen Label Trends. Reported in Milling and Baking News, Aug 30.

Anderson, J.W., Hanna, T.J., Peng, X., and Kryscio, R.J. 2000. Whole grain foods and heart disease risk. J. Am. Coll. Nutr.19: 291S-299S.

Brown, L., Rosner, B., Willett, W.W., and Sacks, F,M. 1999. Cholesterol-lowering effects of dietary fiber: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 69(1): 30-42.

Chan, H.-W., Burgess Champoux, T., Rosen, R., Sadeghi, L., Reicks, M., Marquart, L. 2005. Incorporating white whole wheat flour into traditional grain foods in an elementary school cafeteria. Presented at Whole Grains & Health: A Global Summit, Minneapolis, Minn., May 18-20.

Cleveland, L.E., Moshfegh, A.J., Albertson, A.M., and Goldman, J.D. 2000. Dietary intake of whole grains. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 19: 331S-338S.

Emmer-Aanes, M. 2005. Personal communication. Great Harvest Bread Co., Dillon, Mont., Nov. 2.

FDA. 1999. Whole grain foods authoritative statement claim notification. Docket 99P-2209, Food and Drug Admin., Washington, D.C., July 8.

FDA. 2003. Food labeling: Health claims; soluble dietary fiber from certain foods and coronary heart disease. Final rule. Docket 2001Q-0313, Food and Drug Admin., Washington, D.C., July 28.

FDA. 2004. Citizen petition filed by General Mills, Inc. Food labeling standard for whole grain. Docket 2004P-0223, Food and Drug Admin., Washington, D.C., May 11.

Fulcher, R.G. and Rooney-Duke, T.K. 2002. Whole grain structure and organization: Implications for nutritionists and processors. Chpt. 2 in "Whole Grains in Health and Disease," ed. L. Marquart, J. Slavin, and G. Fulcher, pp. 9-46. AACC Intl., St. Paul, Minn.

HHS. 2000. Healthy People 2010: Volumes I and II. Public Health Service. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Washington, D.C.

Jacobs, D.R.J, Meyer, K.A., Kushi, L.H., and Folsom, A.R. 1998. Whole grain intake may reduce the risk of ischemic heart disease death in postmenopausal women: The Iowa Women’s Health Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 68: 248-257.

Kantor, L., Variyam, J., Allshouse, J., Putnam, J., and Biing-Hwan, L. 2001. Choose a variety of grains daily, especially whole grains: A challenge for consumers. J. Nutr.131: 473S-486S.

Koh-Banerjee, P., Franz, M., Sampson, L., Liu, S., Jacobs, D., Spiegelman, D.,Willett, W.C., and Rimm, E.B. 2004. Changes in whole grain, bran, and cereal fiber consumption in relation to 8-year weight gain among men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 80: 1237-1245.

Liu, S.M., Stampfer, M.J., Hu, F.B., Giovannucci, E., Rimm, E., Manson, J.E., Hennekens, C.H., and Willett, W.C. 1999. Whole grain consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: Results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 70: 412-419.

Liu, S., Willett, W.C., Manson, J.E., Hu, F.B., Rosner, B., and Colditz, G.A. 2003. Relation between changes in intakes of dietary fiber and grain products and changes in weight and development of obesity among middle-aged women. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 78: 920-927.

Lorenzo, C., Okoloise, M., Williams, K., Stern, M.P., and Haffner, S.M. 2003. The metabolic syndrome as predictor of type 2 diabetes: The San Antonio Heart Study. Diab. Care 26: 3153-3159.

Ludwig, D.S., Pereira, M.A., Kroenke, C.H., Hilner, J.E., Van Horn, L., Slattery, M.L., and Jacobs, D.R. 1999. Dietary fiber, weight gain, and cardiovascular disease risk factors in young adults. J. Am. Med. Assn. 282: 1539-1546.

Marquart, L., Chan, H-W., and Jacobs, D.R. 2005. A theoretical model for incorporating whole grain flour into traditional grain foods. Presented at Whole Grains & Health: A Global Summit, Minneapolis, Minn., May 18-20.

Salmeron, J., Ascherio, A., Rimm, E.B., Colditz, G.A., Spiegelman, D., Jenkins, D.J., Stampfer, M.J., Wing, A.L., and Willett, W.C. 1997a. Dietary fiber, glycemic load, and risk of NIDDM in men. Diab. Care 20: 545-550.

Salmeron, J., Manson, J.E., Stampfer, M.J., Colditz, G.A., Wing, A.L., and Willett, W.C. 1997b. Dietary fiber, glycemic load, and risk of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women. J. Am. Med. Assn. 277: 472-477.

USDA/HHS. 2005a. Nutrition and Your Health: Dietary Guidelines for Americans. What Are the Relationships between Whole grain Intake and Health? U.S. Dept. of Agriculture and U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Washington, D.C. www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/report/html/d6_selectedfood.htm. Accessed on 9/16/05.

USDA/HHS. 2005b. Mypyramid.gov. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Washington, D.C. www.mypyramid.gov/pyramid/grains_why.html. Accessed on 9/30/05.

WGC. 2004. Definition of whole grain. Whole Grains Council, Boston, Mass. www.wholegrainscouncil.org/consumerdef.html. Accessed on 10/15/05.

WGC. 2005. Whole grain stamp. Whole Grains Council, Boston, Mass. www.wholegrainscouncil.org/wholegrainstamp.html. Accessed on 11/2/05.